Though it is not remembered principally for this reason, Hillary Clinton’s best-selling book of 1996, It Takes a Village, devoted considerable space to a discussion of brain science and early child development. The headline claim—that “a child’s character and potential are not already determined at birth”—clearly took aim at accounts of human identity that assume it is hardwired from the start. Yet Clinton still cautioned that a child’s “first few years” were the most crucial, because “by the time most children begin preschool, the architecture of the brain has essentially been constructed.”

Clinton’s biological language was telling, and it was not merely metaphorical. More than a generic intervention into the perennial debate about nature versus nurture, it represented a critical rejoinder to Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s infamous argument about race and intelligence in The Bell Curve, which had been published two years earlier—and has cast a shadow over the politics of race and science ever since.

Twenty-five years later, The Bell Curve’s analysis refuses to die.

In Clinton’s view, The Bell Curve had simply been wrong to imply, as she summarized it, that “if nothing can alter intellectual potential, nothing need be offered to those who begin life with fewer resources or in less favorable environments.” This erroneous position, Clinton wrote, went hand in hand with the book’s other “politically convenient” ideas, including that “intelligence is fixed at birth” and that intelligence is “part of our genetic makeup that is invulnerable to change.” Herrnstein and Murray had hijacked the national conversation on the political implications of human biology, putting genetics back on the table as an explanation of enduring “cognitive differences between races.” It Takes a Village sought to rescue the discussion.

This effort both reflected and reinforced a wider attempt to put findings from biology to work as politics and public policy—an attempt that echoes the social Darwinism of the nineteenth century, was deployed through the invidious long career of scientific racism, and endures in various ways to this day across the political spectrum, from the “born this way” logic of one strain of the gay rights movement to fetal heartbeat abortion laws on the right. Even as critics found the The Bell Curve infuriating, they often bought into its methodological premise, that one could draw a clear connection between scientific facts and political conclusions. Not unlike the liberal reaction to the scientific racist backlash against Brown v. Board of Education four decades earlier—which had sought empirical data in the form of raised IQs to buttress its case for desegregation and enrichment programs—both liberal politicians and liberal-minded scientists scrambled to marshal genuine scientific evidence to combat what they characterized as pseudoscience. In place of scientific racism, a kind of scientific anti-racism was born.

Many critics bought into The Bell Curve’s basic premise: that one could draw a clear connection between scientific facts and political conclusions.

A quarter century later, the noble enterprise of seeking to wipe away forever the fake science of The Bell Curve with the real science of early childhood development still remains unrealized. The book’s analysis refuses to die, animated by already existing racial resentment in U.S. politics and culture and helping to fuel more in its turn. In the meantime, additional questions have arisen. Are there dangers to presuming science can be so easily conscripted for political disputation? Is neuroplasticity in essence a liberal’s theory of brain development, or can it also be refurbished to serve policies from the right? Would locating a causal connection between socioeconomic status and early cognitive development finally really banish scientific racism once and for all?

If history is any guide, the legacy of The Bell Curve over the last twenty-five years gives cause for doubt. But reckoning with that legacy may help us redirect the national conversation about race, poverty, and intelligence in urgently needed ways.

Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve appeared in the early fall of 1994 and swiftly rose to bestseller status, selling 400,000 copies in its first two months after publication. It received coverage in nearly every major magazine and newspaper in the country. It was discussed on National Public Radio as well as on popular television news programs, from Good Morning America to Meet the Press.

Clinton’s rejoinder reflected a wider—and enduring—attempt to put findings from biology to work as politics and public policy.

The book made a set of interwoven propositions about race and intelligence. Intelligence tests provide an excellent means of cognitive assessment, it said, and IQ tests are not biased against minorities. It contended that IQ differences exist both within and between racial or ethnic groups, that these group differences in intelligence were likely due far more to “genetics” and much less to “environment,” and that the average IQ for white people was 100, while the average IQ for African Americans was 85. The Bell Curve then used these claims to argue that it was an error to invest so heavily in compensatory educational programs for low-achieving students, since these students were unlikely to benefit meaningfully from these expenditures. It was not, Herrnstein and Murray maintained, that a person’s IQ preordained one’s life trajectory. Rather it was that U.S. society had evolved more or less “naturally” into a hereditary meritocracy. According to The Bell Curve, policy makers and educational reformers had to come to grips with the consequences of this scientific truth.

The book prompted an often passionate outpouring of counterarguments. In October 1994, for instance, New York Times columnist Bob Herbert wrote that The Bell Curve was “a scabrous piece of racial pornography masquerading as serious scholarship.” Herbert bitterly denounced the suggestion that “the disparity” in intelligence between whites and African Americans “is inherent, genetic, and there is little to be done about it” with what must have been one of the longest sentences ever to appear in the paper of record:

I would argue that a group that was enslaved until little more than a century ago; that has long been subjected to the most brutal, often murderous, oppression; that has been deprived of competent, sympathetic political representation; that has most often had to live in the hideous physical conditions that are the hallmark of abject poverty; that has tried its best to survive with little or no prenatal care, and with inadequate health care and nutrition; that has been segregated and ghettoized in communities that were then redlined by banks and insurance companies and otherwise shunned by business and industry; that has been systematically frozen out of the job market; that has in large measure been deliberately deprived of a reasonably decent education; that has been forced to cope with the humiliation of being treated always as inferior, even by imbeciles—I would argue that these are factors that just might contribute to a certain amount of social pathology and to a slippage in intelligence test scores.

Herbert’s scathing takedown was only one of many. Others included the remarks of political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr. (who wrote in The Nation that “despite their concern to insulate themselves from the appearance of racism, Herrnstein and Murray display a perspective worthy of an Alabama filling station”), a review by sociologist Troy Duster (who wrote in Contemporary Sociology of “transparent weaknesses in the structure of the argument and heavily selective use of data”), and the response of paleontologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould (whose scathing critique in the New Yorker observed how Herrnstein and Murray “omit facts, misuse statistical methods, and seem unwilling to admit the consequence of their own words”). Many critics emphasized what they saw as the book’s extensive reliance on fraudulent evidence concerning a genetic basis for human intelligence.

Are there dangers to presuming science can be so easily conscripted for political disputation?

Nonetheless, not all commentators were dismayed. Harvard sociologist Christopher Winship wrote that The Bell Curve might have “serious flaws” but offered a number of “potentially valuable insights,” including the book’s assertion that “cognitive ability is largely immutable.” When the well-respected University of Chicago economist and future Nobel Prize winner James J. Heckman reviewed the book, he observed that the core argument “fails” not least of all because its “central premise” was “the empirically incorrect claim that a single factor—g or IQ—that explains linear correlations among test scores is primarily responsible for differences in individual performance in society at large.” (The g factor had been devised by psychologist and statistician Charles Spearman in the 1930s to denote a quantifiable, innate measure of human intelligence; commentators in the 1990s often used the term interchangeably with IQ, or even considered g more precise.) But at the same time, Heckman acknowledged that The Bell Curve’s “challenge to contemporary assumptions about the malleability of human beings and the relative importance of environmental factors is courageous and long overdue.”

Quite telling as well was the official report on The Bell Curve from the American Psychological Association. Drafted and unanimously approved by a committee of eleven prominent psychologists, the report sought to give a neutral summary of every side of the issue of race and intelligence. It drily concluded, “Explanations based on factors of caste and culture may be appropriate, but so far have little direct empirical support.” Such assessments no doubt provided The Bell Curve a legitimacy both as science and as policy that it would otherwise have been less likely to obtain.

Defenders of The Bell Curve seized the moment. A few months after the book was published, the Wall Street Journal published a full-page opinion piece titled “Mainstream Science on Intelligence.” Signed by more than fifty “experts in intelligence and allied fields” and written by Linda S. Gottfredson, an educational psychologist at the University of Delaware, the statement offered stirring support for The Bell Curve’s guiding principles and asserted that there was a “practical importance” to the science of racial differences in IQ.

Defenders of The Bell Curve liked to argue that it was breaking taboos, even though these were “taboos” that had always been broken throughout U.S. history.

A high IQ could not guarantee success in life, the piece said, and a low IQ did not preordain defeat, but IQ scores were “strongly related” to “many important educational, occupational, economic, and social outcomes.” Employment that required “routine decision making or simple problem solving (unskilled work)” could be handled by individuals with lower IQs, but given that the modern world had grown “highly complex,” it said in very broad strokes, “a high IQ is generally necessary to perform well” in “the professions” and in positions of “management.” The word “complexity” was telling; it was a key term of The Bell Curve’s lexicon. An individual’s ability to grasp “complexity is one of the things that cognitive ability is most directly good for,” the book said, and the inescapable complexity of contemporary life meant that what was easier for “the cognitive elite” was becoming “more difficult for everyone else.” Herrnstein and Murray stressed that a society that failed to acknowledge the key role played by cognitive ability was a society that promoted all manner of inadvertent inequities. (A cognate sort of claim has found renewed resonance today in the writings and videos of the Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson, who contends that the “hierarchies” of modern life are natural and based primarily on “competence.”)

For its defenders, much of the appeal of The Bell Curve resided in the deliberate challenge it posed to post-1960s racial liberalism. Advocates cheered how Herrnstein and Murray disobeyed cultural conventions and used what they said were empirical verities to debunk liberal orthodoxies. According to its supporters, the achievement of The Bell Curve was that it took “mainstream science” to demonstrate (what it said was) a simple fact: all races were not cognitively equal. Defenders liked to argue that it was breaking taboos that needed to be broken—even though these were quite obviously “taboos” that had always been broken in the length and breadth of U.S. history. Before the 1960s, when had there been an age when it was not possible for social scientists to argue openly “from within a biological framework” for “the innate inferiority of people of African descent,” as the historian Daryl Michael Scott put it in Contempt and Pity (1997)? The terrible and tragic paradox of The Bell Curve’s lasting impact on policy discussions of race and intelligence was that it served to promote age-old racial prejudices while insisting that it was just telling it like it really was.

The tragic paradox of The Bell Curve’s lasting impact was that it served to promote age-old racial prejudices while insisting that it was just telling it like it really was.

Gottfredson captured this attitude succinctly. What had caused all the fuss, as she saw it, was that Herrnstein and Murray refused to endorse the “falsehood, or ‘egalitarian fiction,’” that “racial-ethnic groups never differ in average developed intelligence (or, in technical terms, g, the general-mental ability factor).” Anyone who did not dutifully genuflect before this “falsehood,” Gottfredson said, confronted censorship or sanctions both “covert and overt.” Such thinking pitted itself against what it perceived to be strict limits on what one could say in public forums in the United States of the 1990s, especially when what was being said involved “certain truths about racial matters today.” These harsh restrictions on free expression, so the argument went, pressured social scientists into “subordinating scientific norms to political preferences.” (Gottfredson’s lament turned out to be an early exemplar of the now pervasive complaint across the right about the purportedly narrow range of political speech allowed on college campuses and the continually recharged debates about “political correctness.” The technique—insisting that one is not being permitted to express negative assessments of groups who have suffered historical injustice, all the while loudly doing so—has become ever more widespread and effective in the last few years.)

Meanwhile, liberals were positioned as ones who cannot acknowledge facts. “Nothing frightens the liberal mind more,” Gottfredson is quoted saying in Dinesh D’Souza’s 1995 book The End of Racism, “than the prospect of inherited differences in intelligence between the races.”

Gottfredsons’s smirking aphorism neatly summarized the plight of anti-racist scientists and liberal policy makers by the end of the century, as right-wing activists reveled in the ideological conflagration The Bell Curve had sparked. Both political and scientific efforts soon took off to articulate an alternative perspective that underscored the plasticity of brain development in early childhood.

In the wake of The Bell Curve, a scramble to locate scientific proof to justify liberal policies became primary.

For their part, researchers sought to identify a causal—not merely correlational—relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and cognitive function in the developing brains of young children. Much of this research has relied on its own version of a theory of neuroplasticity, seeking to prove that such plasticity renders a poor child both especially exposed to environmental harms and remarkably susceptible to early educational enrichments. Yet although the scramble to locate scientific proof became primary, researchers continued to argue for the ethical imperative to endorse early education intervention—even (or even especially) while causal factors remained unresolved.

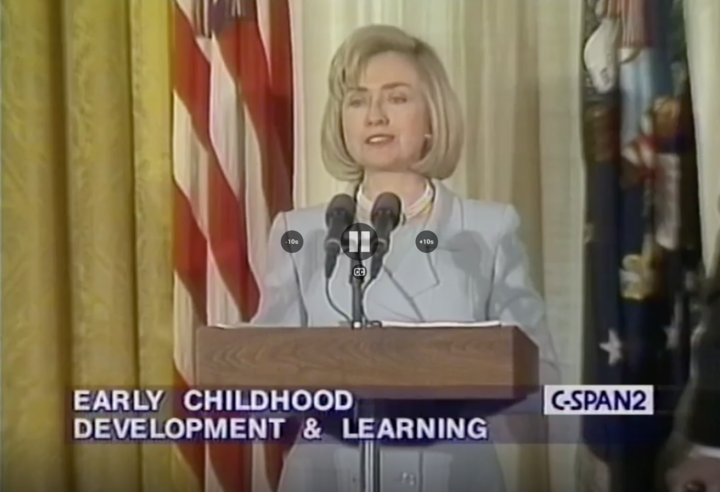

On the political side, the Clinton White House hosted a conference in April 1997 on “What New Research on the Brain Tells Us about Our Youngest Children” (video of which is still available on C-SPAN). Experts from several fields were invited to speak. The president brought it all together when he announced plans to extend health care coverage and expand early educational opportunities for poor children. The key mission of the conference was unequivocal: use the new science of early childhood development to shine a spotlight on the deleterious impact that impoverished environmental conditions can have on a child’s brain.

These efforts became the subject of a far larger and more sustained media blitz aimed at educating the general public specifically about the political implications of the concept of neuroplasticity in young children. A nationally broadcast ABC-TV program, I Am Your Child, aired that spring, coinciding with the release of “Your Child: From Birth to Three,” a special edition of Newsweek magazine that sold more than a million copies. In its discussion of brain plasticity, Time magazine too laid bare its progressive leaning when it stressed how there existed an “urgent need, say child-development experts, for preschool programs designed to boost the brain power of youngsters born into impoverished rural and inner-city households.” Collectively these news reports deliberately sought to turn political discussions away from the reasoning in The Bell Curve that used biology to reduce educational assistance for disenfranchised children and toward a liberal logic that invoked biology to increase funding instead. Biology played a central role in the political calculus on both sides.

That the child’s brain was plastic and that it developed in relation to environmental factors were hardly novel perspectives in the 1990s. From the 1940s to the 1980s, neuroanatomists and developmental psychologists had demonstrated in animal studies and extrapolated to humans that “neural change” could be “induced by experience” and that the development and pruning of synapses was either “experience expectant” or “experience dependent.” In 1993 developmental psychologist Craig Ramey argued that policy makers would never have been able to ignore the level of knowledge about the vulnerability of poor children’s neural development “if we had a comparable level of knowledge with respect to a particular form of cancer, or hypertension or some other illness that affected adults,” but since “young children don’t vote, and they can be sort of kept hidden for a while until they show up in the school system failing miserably,” their difficulties could be more easily neglected.

Ramey, along with his wife and frequent collaborator, the developmental psychologist Sharon Landesman Ramey, did not hesitate to single out Herrnstein and Murray for critique. Among other things, they wrote that emerging “empirical evidence on biobehavioral effects of early experience” should finally lay to rest the “erroneous explanation” for “educational and cognitive inequalities” that remained “alive and socially influential even today” as demonstrated by “the popularity” of The Bell Curve. A New York Times editorial in 1997 made its allusion to Herrnstein and Murray only slightly more oblique when it noted how “many people have accepted the notion that the brain has been genetically determined by the time a baby is born” but that “research by neuroscientists, however, shows that after birth, experience counts even more than genetics.” The Bell Curve, or at least what The Bell Curve was said by its critics to represent, lingered in late-1990s discussions on how (and why) neuroplasticity should inform policies on early intervention.

To be clear, Herrnstein and Murray had said nothing whatsoever about synaptic development in early childhood. Plasticity was not a concept they considered relevant or worthy of attention. Yet for their opponents, it was essential. The effort to show that the science of neuroplasticity was indispensable for understanding early childhood development was manifestly intended to demonstrate that The Bell Curve’s analysis, its archive, and everything it stood for had been both selective in its choice of evidence and slanted by its ideological intent.

A theory of neuroplasticity began to have direct effects on early education policies.

For a time, the opponents’ efforts paid off, and a theory of neuroplasticity began to have direct effects on early education policies. Governors in at least a dozen states requested that more monies be allocated for early education programs, and California governor Pete Wilson cited specifically the science of early brain development when he asked that more than $740 million be added to the state budget for child assistance. The Early Childhood Development Act of 1997, whose key sponsor was Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts, stated that “new scientific research shows that the electrical activity of brain cells actually changes the physical structure of the brain itself and that without a stimulating environment, a baby’s brain will suffer.” This federal legislation appropriated $1.5 billion each fiscal year to support good “childhood learning services,” especially for the 25 percent of children under the age of 3 in the United States who were living in poverty. Taken together, these initiatives came to represent—as worthy as their ends might otherwise have been—a full-scale “politicization of research on early brain development and child development.”

The pattern continued into the first decade of the new century. In 2000 the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine jointly published From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. A former member of the board of directors for the child advocacy organization Zero to Three, pediatrician Jack Shonkoff, coedited the report with developmental psychologist Deborah Phillips, who had spoken at the Clinton White House conference in 1997. It was the most comprehensive study of its kind. “It is not nature versus nature,” the report stated: “it is rather nature through nurture. . . . The two should be understood in tandem.” Indeed, “at every level of analysis, from neurons to neighborhoods, genetic and environmental effects operate in both directions.” The report was cautious in its pronouncements. “To disentangle established knowledge from erroneous popular beliefs or misunderstandings” was not an easy task, it said. And strategically, the report openly criticized both sides of the debate over early childhood intervention for perpetuating what it said was a “siege mentality” between “those who support massive public investments in early childhood services and those who question their cost.”

In the 2000s opponents of The Bell Curve came to see brain science as having made their case for them.

From Neurons to Neighborhoods prudently concluded that science alone could not settle this “conflict between advocates and skeptics.” The fact of neuroplasticity in human development was cause for optimism, even while it also generated cause for apprehension. As the report put it, “plasticity is a double-edged sword that leads to both adaptation and vulnerability.” Herrnstein or Murray were not mentioned by name. But the report’s central argument certainly emphasized the malleability of human development in response to particular life experiences. These perspectives, taken together, served as counterpoints to the arguments of The Bell Curve.

The class-based themes and color-blind arguments in From Neurons to Neighborhoods came to dominate the new century’s literature on the science of early childhood. Opponents of The Bell Curve came in these years to see brain science as having made their case for them. They began to sound as if the war had been won. In 2007, when the journal Educational Leadership invoked the increasingly “robust” findings that demonstrated “that, under the right conditions, early intervention can dramatically improve the odds for children at risk,” it could not resist taking a jab at Herrnstein and Murray for their “profound skepticism that any form of education intervention can alter the cumulative negative toll that poverty and other disadvantages take on the development of young children.” The journal went on to say that thanks to the new science of child development, it appeared possible once and for all “to explode the myth that nothing works.”

But was The Bell Curve truly dead?

A problem for some critics was that The Bell Curve had not actually discounted the impact of environmental factors on intelligence, as many assumed. Herrnstein and Murray liked to tell the story of “two handfuls of genetically identical seed corn,” where one is planted “in Iowa, the other in the Mojave Desert,” only then to “let nature (i.e. the environment) take its course.” The punchline? “The seeds will grow in Iowa, not in the Mojave, and the result will have nothing to do with genetic differences.” They then pointed out, “The environment for American blacks has been closer to the Mojave and the environment for American whites has been closer to Iowa.” Moreover, Herrnstein and Murray repeatedly stated that “environment” did play a part in shaping racial differences in intelligence, even as they insisted that “genes” played a role as well. “It seems highly likely to us,” they wrote, “that both genes and the environment have something to do with racial differences. What might the mix be? We are resolutely agnostic on that issue; as far as we can determine, the evidence does not yet justify an estimate.” It was a claim too vague to be completely contradicted.

Rather than being seen as an obstacle for conservative politics to evade, the concept of brain plasticity came over time to serve a right-wing agenda.

The environment, in short, did matter to Herrnstein and Murray. This was evident not just in their vignettes about poor children who suffered “inadequate nutrition, physical abuse, emotional neglect, lack of intellectual stimulation, a chaotic home environment—all the things that worry us when we think about the welfare of children.” The environment factored heavily as well in their discussion of children from the “cognitive elite.” For despite their emphasis on the genetics of human intelligence, Herrnstein and Murray observed that these children had to see their talents actively nourished. Cognitive brilliance might be innate, but—like seed corn—it required the educational equivalent of Iowan soil.

It was no contradiction, then, for The Bell Curve to promote policies that called for more funding to be funneled to America’s high-IQ (and, incidentally or not, often white) students. The book condemned “the neglect of the gifted.” It cited federal budget statistics that saw more than 90 percent of educational funding going to “the disadvantaged,” while a mere tenth of 1 percent went to “programs for the gifted.” It expressed horror at these numbers, and it urged policy makers to radically reallocate federal funds to “intellectually gifted” children who, Herrnstein and Murray argued, should be permitted to reap the rewards of their own intelligence—“not because they are more virtuous or deserving but because our society’s future depends on them.” Until such time as these monies were spread more evenly across the children of the bell curve, there would continue to be a public school system in the United States that failed children on nearly every front—neither managing to assist the disadvantaged child nor serving properly to encourage the brightest children so that they might develop their fullest potential.

Furthermore, rather than being seen as an obstacle for conservative politics to evade, the concept of brain plasticity in early childhood thus came over time to serve a right-wing agenda. In 2005, when researchers observed that it was time for “a paradigm shift” in their field of gifted education, they noted that it was no longer possible to think of “some children as innately having brains that work unusually well.” It was far more appropriate to conceptualize “intelligence as a developmental phenomenon that is importantly dependent on a child’s opportunities to learn.” These points resembled those made in From Neurons to Neighborhoods, except for the very different category of children it aimed to assist. Then in 2008 Charles Murray too weighed in, writing that “important evidence has been found for the plasticity of certain mental processes, especially during infancy and early childhood.”

Biology could be appropriated and applied as a rationale to advance policies across the political spectrum.

For Murray the science of brain plasticity no longer needed to be viewed as a threat to the right’s education policies. On the contrary, he invoked plasticity in the midst of a jeremiad against an “educational system that cannot make itself talk openly about the implications of diverse educational limits,” one that perpetuated “a fog” of “well-intended egalitarianism” and “educational romanticism.” Once again, then, righteous indignation at the constraints of “political correctness” was the tactic of choice. Now with plasticity on his side, Murray reprised the The Bell Curve’s core analysis, insisting that education policy in America currently failed all students—not only the students who were “below average” but also “those who are lucky enough to be academically gifted” and who “will play a crucial role in America’s future.”

Thus a focus on environment and brain plasticity came to be used to advance policies for gifted education, and to undermine the position that only disadvantaged children required enrichment. Neuroplasticity may have once been a pet theoretical concept adduced by liberal policy makers and politicians in order to make a case that more monies be directed to impoverished children, but no longer. Biology could be appropriated and applied as a rationale to advance policies across the political spectrum.

Meanwhile, the hunt for firm evidence that early educational intervention improved cognitive function for children of the poor has continued to the present day. Developmental psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Kimberley G. Noble wrote in the Washington Post in 2015, “The political battles for major expansion of these types of programs are unlikely to be won until we can provide hard scientific proof of their effectiveness. Until then, we need to do all we can to support policies that offer our most vulnerable children the best chance of reaching their full potential.” And in 2016 the journal Pediatrics also described research on interventions that might undo the neurocognitive damages of poverty to the developing brain as still very much “in its infancy,” adding, “Perhaps most urgently, experimental studies that assess the impact of changing SES on brain development are needed to determine causal links.” However inadvertently, these statements conceded quite a lot about the fragility of their own case.

Rather than calling for remediating childhood poverty as a baseline social goal—in purely political or moral terms—commentators often got tangled in their efforts to adduce biological evidence.

Has the search for “hard scientific proof” been an instance of needing to be careful what you wish for? As early as 2003 the journalist Ann Hulbert had suggested as much. Arguments that emphasized the damage done to “young brains subjected to deprived conditions” could well serve to “inspire a liberal social agenda,” she wrote. But it remained equally possible, Hulbert cautioned, that a “reading of the data” could “all too easily fuel defeatism” and “just as readily be invoked in the service of a deeply pessimistic position that was not at all what they intended.”

The insight was prescient. In 2009, when University of Pennsylvania cognitive psychologists Daniel A. Hackman and Martha J. Farah surveyed the available neuroscientific literature on the effects of poverty on the developing brain, they came to a similar conclusion. “Although the cognitive neuroscience of SES has the potential to enable more appropriately targeted, and hence more effective, programs to protect and foster the neurocognitive development of low SES children,” they wrote, “it can also be misused or misunderstood as a rationalization of the status quo or ‘blaming the victim.’ . . . The biological nature of the differences documented by cognitive neuroscience can make these differences seem all the more ‘essential’ and immutable.” Put another way, would solid proof of this or that biological relationship necessarily support the policy arguments already being made on other grounds? Rather than calling for remediating childhood poverty as a baseline social goal—in purely political or moral terms—commentators often got tangled in their efforts to adduce biological evidence while worrying that it could be turned against their cause.

In the 2006 revised and expanded edition of his masterwork, The Mismeasure of Man (1981), Stephen Jay Gould observed in his comments on the legacy of The Bell Curve that “innatist arguments for unitary, rankable intelligence” are “always present, always available, always published, always exploitable.” Resurgences in biological determinist thought, Gould wrote, consistently

correlate with episodes of political retrenchment, particular with campaigns for reduced government spending on social programs, or at times of fear among ruling elites, when disadvantaged groups sow serious social unrest or even threaten to usurp power. What argument against social change could be more chillingly effective than the claim that established orders, with some groups on top and others at the bottom, exist as an accurate reflection of the innate and unchangeable intellectual capacities of people so ranked?

This remains a trenchant analysis; indeed it sounds as though it could have been written today. Yet it may also obscure the degree to which the causation runs in both directions.

For it is not just that such arguments about the supposed biological links between race and intelligence reflect already existing resentment among white people, of whatever class status, toward the less fortunate in their midst. These arguments are also purposive and productive, breeding more of the same. To study the long history of their promulgation is to notice that, over and over, they have served above all two purposes: to soothe white egos, especially in times of declining prospects for almost everyone, and to pull public funding away from the most vulnerable. And they have also served a third purpose: to redirect public attention away more generally from massive structural economic and political inequities. Among the central challenges for their political opponents today is how to reorient the national conversation away from the terms of The Bell Curve and how best to reinvigorate the public’s imagination about what is moral and politically good.

Editors’ Note: This essay is adapted from the author’s book The Mismeasure of Minds: Debating Race and Intelligence between Brown and The Bell Curve. Copyright 2018 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.