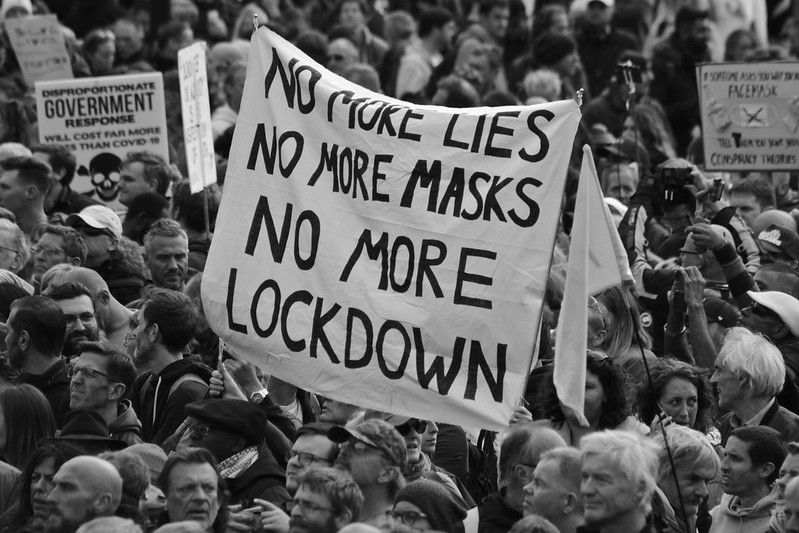

Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not.

Led by angry freelancers and the self-employed, a range of new movements share the conviction that all power is conspiracy.

Taking a cue from one of the movements itself—Querdenken in Germany, in particular—we call the strategy behind the diverse movements “diagonal thinking” and the broader phenomenon they represent “diagonalism.” Bridging the more familiar concept Querfront and the more recent term Querdenken, the idea of “diagonalism” exceeds the German context of its coinage, where it means something like out-of-the-box thinking. Born in part from transformations in technology and communication, diagonalists tend to contest conventional monikers of left and right (while generally arcing toward far-right beliefs), to express ambivalence if not cynicism toward parliamentary politics, and to blend convictions about holism and even spirituality with a dogged discourse of individual liberties.

At the extreme end, diagonal movements share a conviction that all power is conspiracy. Public power cannot be legitimate, many believe, because the process of choosing governments is itself controlled by the powerful and is de facto illegitimate. This often comes with a dedication to disruptive decentralization, a desire for distributed knowledge and thus distributed power, and a susceptibility to rightwing radicalization. Diagonal movements trade in both familiar and novel fantasies about elite control. They attack allegedly “totalitarian” authorities, including the state, Big Tech, Big Pharma, big banks, climate science, mainstream media, and political correctness. They are, in many ways, descendants of the extra-parliamentary New Social Movements of the 1970s but with the idealism and desire for collective action or decommodification burned down to the wick of a defense of autonomous decision-making.

It would be easy to dismiss such mobilizations as manifestations of conspiratorial thinking, morbid symptoms of a morbid year with the United States acting as a “superspreader” of distrust, as one source told the Washington Post. But as the cultural theorist Jeremy Gilbert recently pointed out, “conspiracy theory” has many of the failings of the earlier category of “populism”: it is too often used prematurely to foreclose a form of politics as illegitimate and, by othering it, can grant it the mark of martyrdom its followers seek.

An old axiom of political science dictates that governments rule by “carrots, sticks and sermons”—that is, coercion and incentive but also information. Diagonalism reminds us that universal Internet access, the attention-absorbing power of social media platforms, and the dynamics of “incitement capitalism” have left the state’s official script ragged with perforations and made space for hostile counterpublics, agents of “disinfotainment,” social movements of rabbit holes, gig conspiracies for the gig economy. We have no choice but to wade in.

Revolt of the Mittelstand

Efforts to name the snowballing movements—incorporating a range of anti-government, anti-lockdown, anti-mask, and anti-vax positions—have been strained so far. Beyond the United States, where support for the recently defeated president offers a convenient common denominator, most observers have made heterogeneity the takeaway. The Economist referred to the “diverse bunch” at demonstrations that often feature New Age homeopaths next to skinheads and QAnon supporters in stars and stripes. “Meet Germany’s Bizarre Anti-Lockdown Protesters” read the title of a New York Times op-ed in August. Naomi Klein referred to the “conspiracy smoothie” that unites many protesters. Sociologist Keir Milburn hazarded the coinage of “the cosmic Right.” Drawing lessons from the mass phenomenon that is Bolsonarismo, Brazilian philosopher Rodrigo Nunes described the protests as the latest manifestation of “denialism” born of an inability to come to terms with the enormity of challenges confronted by humankind.

Diagonalism reminds us that “incitement capitalism” has made space for hostile counter-publics.

Yet the first academic study of the “coronaskeptic” movement in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland puts even these tentative labels into question. Sociologists at the University of Basel find that, in German-speaking countries anyway, right-wingers do not completely dominate the movement. In the most recent election, the largest percentage of those active had voted for the Greens (23 percent) and the second for the Left Party (18 percent) followed by the right-wing Alternative for Germany (15 percent). The majority showed no particular antagonism to foreigners or Muslims nor did they believe that women should return to traditional roles. Most denied neither the science of climate change nor the Holocaust. One denialism did not imply all others.

What they did believe in was a high level of elite closure suturing together media, government, big business, and finance. They feel that the media and the state were working to create excessive fear in the population, conceal the truth, and deceive the people. Nearly two thirds believed the Bill and Gates Melinda Foundation want a forced vaccination for the whole world.

From a class perspective, the movement was far from lumpen. Participants mostly self-identified as middle class and were disproportionately self-employed (25 percent compared to 9.6 percent in Germany overall). Protests worldwide have frequently been led by small business owners and the self-employed, who conventionally lack the social ties of trade union membership and have less job security than civil servants or the employees of larger businesses permitted to work from home in “white-collar quarantine.”

Small-business owners and the self-employed have reason to be angry. The so-called “K-shaped recovery” has favored large corporations, which have reaped gains—and access to credit from both private and public sources—as smaller enterprises suffered. This has been most marked for providers of in-person services. In some of the more notable examples of escalating frustration, men armed with assault rifles stood guard at a Dallas hair salon that refused to close in April. In October, restaurant owners in chef’s hats demonstrated in the streets of Rome as a trumpet played “Taps” for their businesses. In London, a gym owner who refused to close his business was among twenty-nine people arrested as five police officers were injured in a protest against the city’s return to Tier 4 lockdown.

Discontent extends beyond those in the streets. Surveys show that about 42 percent of the German Mittelstand—those owning and operating small- and medium-sized enterprises—find the government response to the pandemic either “bad” or “very bad.” While many small-business owners in Germany and elsewhere express frustration about insufficient governmental responses—which vary drastically by country in support via direct payments, supplemental wages, and unemployment insurance—most simply want the government to do its job effectively and have no truck with wild online fictions. Yet with a growing proportion of the population exposed to disinformation through social media and video platforms, it is unsurprising that a considerable minority (a minimum of 10 percent in most countries) has found its way into some dimension of diagonalism.

What to call the more extreme form of opposition? “Anti-lockdown” fails to capture the breadth of the critique, which extends for many from what the French call le confinement to skepticism about masks, vaccination, and frequently to the reality of the pandemic itself. Viral films such as Plandemic and Hold-Up, with an estimated viewership of over 9 million (via YouTube alone) and 6 million respectively, describe the pandemic as a pretext for global elites to roll out a thoroughgoing transformation of everyday life. Some 80 percent of those questioned in the German-language poll thought COVID-19 was no worse than a bad flu, while 84 percent said they would not accept a vaccine even if it was guaranteed to have no side effects.

Our label for the movements is derived from another that can be spotted in clean sans serif font on T-shirts and signs everywhere at protests in German-speaking countries: Querdenken.

For decades, Querdenken has circulated in C-Suite Powerpoint argot alongside cognates like “disruption” and “thinking outside of the box.”

The term Quer, most often translated as “lateral” or “transverse,” also means “diagonal” or “across”; a Querschnitt of the population is a cross-section. It recalls the often-discussed concept of Querfront, which linked “red” communist and “brown” fascist movements of the interwar period. Yet it has a very different origin, stemming from the jargon of marketing and consultancy. For decades, Querdenken has circulated in C-Suite Powerpoint argot alongside cognates like “disruption,” “thinking outside of the box,” or the dot-com era Apple injunction to “think different.” A business magazine called Querdenker existed between 2009 and 2014. The etiology of the term is apt, capturing a politically diverse group of actors united under a piece of formally empty jargon native to the world of media consulting—a world, as we will see, from which many of the movement’s organizers came.

What makes the current situation combustible are precisely the freelance media hustlers, movement messiahs, and entrepreneurial contrarians who have every motivation to sharpen social tensions as they seek to create new poles of authority and often self-enrichment. The current state of the diagonal movement in Germany is especially telling. Three types central to the German scene are becoming staples across different contexts of techno-political turbulence globally. They offer stand-ins, repeated in different embodiments from country to country: the Movement Hustler, the Left-to-Right Ideologue, and the Far-Right Esoteric.

The Movement Hustler

In August two “anti-covid” protests were held in Berlin, the first with 20,000 participants and the second with 38,000. The first event, called the “Day of Freedom,” featured speakers and performers on a large stage in the middle of Strasse des 17 Juni, the mostly maskless crowd spanning from the Brandenburg Gate to the Berlin Victory Column. Officials expressed concern about the maskless gatherings of individuals with heterogeneous outlooks: hippies, antiwar activists, libertarians, constitutional loyalists, anti-state monarchists (Reichsbürger), neo-Nazis, alternative medicine practitioners, anti-vaccination campaigners, and apolitical left-liberals, among others. Nonetheless, it was a comparatively tiny far-right protest that nearly burst through the doors of parliament, described as “the storming of the Reichstag,” which dominated public debate for weeks.

Standing on stage in Berlin on August 1 was Michael Ballweg, a Stuttgart-based entrepreneur and IT developer with a number of start-ups to his name. In 1996 Ballweg founded Media Access GmbH, which sells “senior expert management” software and services allowing companies to “reactivate” retired employees for consultation on specific projects. One summer night when his thirteen-year-old daughter missed her 9 p.m. curfew, an anxious Ballweg resisted the urge to call her and instead innovated an app called Synagram Kids. Using the GPS function on cell phones, the app sends parents automatic notifications with location-tracking when children fail to arrive at a predetermined location by the scheduled time.

“I am here today because I dislike the world the federal government presents to me,” Ballweg said on stage in Berlin. Although he does not deny the existence of the virus, he insists that “there is no pandemic” and thus no need for allegedly unconstitutional state interventions. “Querdenken comes from the English letter Q for question,” he explained, meaning “second-guess the source.” Like a good entrepreneur, Ballweg copyrighted Querdenken in 2020. In August, his Media Access company issued a statement on its website, titled “On the Status of Democracy,” alleging that large customers like Bosch and Thyssenkrupp terminated their contracts due to Ballweg’s activism, a claim disputed by these companies. Ballweg has since presented himself as a victim of politically motivated censorship, and in September he announced the sale of Media Access.

What unites such variants of “left” and “right” thinking is less their common goals than their shared enemies.

Since becoming a full-time movement hustler, Ballweg has received greater scrutiny for Querdenken’s finances. The group requests monetary contributions by PayPal or bank transfer, flowing directly into Ballweg’s account. Querdenken describes itself as an “initiative” rather than a “foundation” and can thus avoid taxes on donations. In this way it also bypasses certain problems that come with collectively run political organizations—such as those that plagued Sahra Wagenknecht’s Aufstehen (Stand Up) movement from 2018-19—all while developing a similar “basis democracy” structure of self-organized groups (like Bochum #234 or Oldenburg #441) which purchase their banners, T-shirts, and signs from Stuttgart (#711). Ballweg has also profited by striking big-money deals with various partners, from bus companies that transport protesters around the country to fringe figures like a former sex film mogul who doled out 5,000 Euros to dance on Querdenken’s stage.

After receiving pushback for its tolerance of neo-Nazi attendees and lack of transparency, Querdenken has threatened journalists with defamation lawsuits. It also formally denounced “both left and right extremism” while giving shout-outs to the hardly “centrist” U.S.-derived QAnon movement. Yet Ballweg insists “we have no political partners because we are not a political movement or a political party. We are a democratic movement out of the middle of society.”

Ballweg’s lack of transparency is paralleled only by a lack of charisma, making him more like the Five Star Movement’s controlling tech guru Davide Casaleggio than its comedian cofounder Beppe Grillo, more political consultant than crowd-pleasing thespian. The diagonal ideas developed by Querdenken, however, outshine even the most conspiratorial elements of Five Star. And its digitally driven theater has run on backstage alliances with a diverse group of media entrepreneurs who elude conventional labels.

The Left-to-Right Ideologue

On Querdenken’s ostensible “left wing” is KenFM, an Internet journalism portal founded by Ken Jebsen. Once an antiwar activist and public radio host, Jebsen was fired from his job for anti-Semitic comments. Ever since, KenFM has amassed a considerable following on YouTube, social media, and its crowdfunded website, thanks to the host’s lightning-speed interviews with an eclectic and provocative group of authors, scholars, and artists.

With attention-grabbing titles like “Transnational Elite-Fascism,” “Down with the Digital Dictatorship,” and “COVID 19: A Trojan Horse, European 9/11?,” KenFM’s pseudo-intellectual style stitches together anti-elite discourse with the conservative controversy of the day, be it migration policies, corruption scandals, or coronavirus measures. With close-up videos that showcase Jebsen’s authoritarian flair, the program blurs Kapitalismuskritik and anarcho-capitalism, bringing together left-leaning critics like Rainer Mausfeld and Ullrich Mies with right libertarians like Markus Krall and Max Otte.

What unites such variants of “left” and “right” thinking is less their common goals than their shared enemies. From “mega-manipulation” to “mass censorship,” they all paint a dystopian picture of the conspiracy of power. Outside of KenFM many other diagonal partnerships have formed, such as the podcast “Multiculturalism Meets Nationalism” in which the Ghanaian-German “lifestyle entertainer” Nana Domena dialogues with the neo-Nazi Frank Kraemer. Oddities and nuances aside, the pandemic has allowed the diagonalist “resistance” to focus its critique on the spatial containment and physical restriction imposed by the government, often embodied by Chancellor Merkel (or “Merkill”) herself. Concepts like “freedom” and “democracy”—especially the freedom of assembly—become a battle cry against the “totalitarian” and “fascist” forces “up above” (in German, die da oben).

These figures can unite around portals like KenFM due to their shared opposition to Big Tech. Many, if not most, of the Querdenker have been “cancelled” themselves. When removed from platforms like YouTube for spreading unfounded conspiracies, they decry their loss of “free speech” and “constitutional rights” and often blame the government for their newfound unfreedom. Like EinProzent and many other far-right groups, KenFM’s page was recently taken down from YouTube after two warnings from the company, thus losing hundreds of thousands subscribers, millions of views, as well as the income stream that comes with them.

Given plausibility through such a wave of account deletions and interventionist acts of flagging and censorship by platforms like YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook, Querdenken’s coronaskeptics have followed libertarian and far-right leaders to a growing number of alternative platforms, including BitChute, DLive, Gab, MeWe, Odyssey, Parler, Periscope, Patreon, Rumble, Substack, Telegram, Twitch, and VK.

Paradoxically, the broader turn of the public mood against Silicon Valley and the upsurge in discussion of what Shoshana Zuboff has called “surveillance capitalism” has been sharpest in the very diagonal movements that rely on it most for their existence. The diagonal anxiety is that their own decentralism is made possible by such platforms, which are themselves embodiments of highly concentrated corporate power. The permanent expulsion of Trump from his preferred platform of Twitter will surely energize a host of new alt-platforms promising unmitigated “free speech” to the victims of past or potential censorship.

Through the fantastical escape from Big Tech, diverse groups can coalesce around an everything opposition, a Great Refusal to the conspiracy of power.

For its part, Querdenken has seized on Telegram as its preferred alternative among the range of options. The platform is ideal for sending or forwarding messages with links and for coordinating local protests in real time—one reason it is popular among left activist groups as well. Alongside WhatsApp groups, Telegram has exploded since the beginning of the pandemic, paralleling YouTube and Facebook as prime circulators of conspiracies. If WhatsApp groups foster a sense of community among strangers with a centripetal force that breeds paranoia to outsiders, as Will Davies observed, Telegram breeds an amorphous community driven by a more centrifugal force. This is partly due to the cap of 256 users per WhatsApp group, versus 200,000 for Telegram.

Subscribing to a Telegram channel means receiving dozens to hundreds of messages on your phone per day. Among the thousands of channels based in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, some are devoted to dubbing English-language videos into German, primarily using content from Fox News, OAN, and Newsmax. The largest channels, averaging between 50,000 and 200,000 subscribers and growing, send misinformation on an eclectic range of topics from U.S. election fraud, to Bill Gates’s “depopulation” agenda, to the European Central Bank’s plan to debauch the currency, to esoteric sunset memes about world peace.

The articles and messages that circulate across German-language Telegram channels are largely linked to “alternative journalism” websites like KenFM, including Epoch Times Deutschland, Nachdenkseiten, Reitschuster, Rubikon, TichysEinblick, and others. Together they propel a new kind of political hybridism, a breeding ground for anti-authoritarian authoritarianism.

Through the fantastical escape from Big Tech, diverse groups can coalesce around an everything opposition, a Great Refusal to the conspiracy of power.

The Far-Right Esoteric Entrepreneur

Self-portrayal as minoritarian resistance is a defining feature of diagonalism, and one that makes diagonalists ready allies of voices in rightwing media who represent minority opinions on issues from vaccination to climate change to immigration and race science, which they seek to represent as the true voice of the people. Whether denying the existence of the virus, downplaying its effects, or citing “alternative science” experts like Sucharit Bhakdi and Wolfgang Wodarg, Germany’s coronaskeptic community proudly runs against the grain. Among its celebrity ranks are Xavier Naidoo (the former winner of Germany’s equivalent of American Idol), Attila Hildmann (the vegan chef turned ultranationalist anti-Semite), and Eva Herman (the former news anchor and best-selling anti-feminist libertarian). Generation Z is represented by youthful provocateurs like Naomi Seibt (the so-called “anti-Greta” fostered by climate-denialists at the Heartland Institute) and Neverforgetniki (the so-called “anti-Rezo” whose anti-government monologues regularly rack up hundreds of thousands of views).

Diagonalists are ready allies of rightwing voices, from vaccination to climate change to immigration and race science.

Yet Querdenken’s movement hustlers, who appear on stage at Ballweg’s demonstrations and on every social media platform that hasn’t banned them, embrace a minoritarian conception of “the people” with a peculiar genealogy: the far-right underworld of esotericism and alternative medicine.

A central figure in this scene is Michael Friedrich Vogt. During his graduate studies in Munich, Vogt became a leader in rightwing fraternities and neo-Nazi student groups while writing his dissertation on Marx and Engels’s philosophical anthropology. After almost a decade as lecturer in Media and Communication Studies at the University of Leipzig he was expelled for meeting with far-right groups and making a revisionist documentary film about Adolf Hitler’s Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, a fan-favorite in the underground genre. Thereafter he cultivated a network of “brown-esoteric” entrepreneurs, founded Reichsbürger-adjacent organizations like “Aufbruch Gold-Rot-Schwarz,” and wrote in print calling for “the destruction of the existing party-run state” and “the establishment of a truly sovereign people.”

In the early 2010s Vogt founded a web-financed site called Quer-denken.tv, a “free platform for free spirits” featuring “non-conforming diagonal minds.” Part of the self-described “truther scene,” Querdenken.tv produced conspiratorial articles and videos on topics like chemtrails, vaccines, and pandemics, including a 2014 piece called “Is the Ebola Pandemic a Lie?” Vogt participated in the Anti-Censorship Coalition and organized the annual Querdenken Congress which, from afar, appeared as a harmless if quirky set entrepreneurs exchanging ideas, selling expensive if senseless products, and conducting paid interviews against “far out” backdrops.

Upon closer inspection, however, the Querdenken Congress was anything but harmless. Under the title “Everything is Connected,” the 2015 meeting mixed a cocktail of “conspiracy theories, resentment, and esotericism” featuring rightwing celebrities like Nigel Farage, Eva Herman, and Andreas Popp. An hour’s train ride from Frankfurt in the small town of Friedberg, various unions, churches, and political parties protested the esoteric exhibition of rightwing entrepreneurialism. Precisely this kind of public reaction is why Vogt has attempted to book the annual event just days before the actual meeting, and then inform attendees of the location by email, lest critics expose them and pressure venues to cancel their contracts.

A number of Querdenken’s leaders have emerged out of Vogt’s circle. Among them is the esoteric entrepreneur Heiko Schrang, who mastered the art of monetization (and meditation) long before building his massive following on Telegram, YouTube, and other platforms. Schrang is the founder of a press called Macht-steuert-Wissen (Power-controls-Knowledge), which is more online shopping mall than publishing house, though it has released books like Being: The Art of Acceptance, Cultural Marxism: An Idea Poisons the World, and Germany Out of Control: Between the Loss of Values, Political (In)Correctness, and Illegal Migration. Schrang’s war against publicly funded media is personal, as he has refused to pay the government “TV tax” since at least the Querdenken Congress in 2016, making him an ally of the AfD on the issue and a hero to followers who celebrate his resistance outside his courthouse hearings. Though he would not put it this way himself, his credo could be: trust no one but markets, especially not corporations.

Another Querdenken leader is Samuel Eckert, a former lay preacher expelled from his Seventh-day Adventist Church for sermons containing anti-Semitic and coronaskeptic elements. Also a poker professional and a managing director of several businesses, Eckert moved to Switzerland in 2016 after watching a Querdenken.tv advertisement. A focus of his current Querdenken activism is youth participation and fundamentalist Christian outreach. “Querdenken is a religion that you have to internalize,” he explains.

Alongside Schrang and Eckert are other fringe innovators of far-right thought like Jürgen Elsässer (owner of the far-right magazine Compact), Oliver Janich (former president of the libertarian Party of Reason), Thorsten Shulte (noted anti-Semite and author of Foreign-Controlled: 120 Years of Lies and Deception), and Bodo Schiffmann (an otorhinolaryngologist who made headlines for claiming “children are dying because they are wearing masks against an illness that doesn’t exist”).

Typical of diagonal entrepreneurs worldwide, the Querdenken cohort battles the “Corona Dictatorship” on behalf of the “Truth Movement” while making a buck on the side.

Ungovernable Diagonalists

In a moment reminiscent of the summer of 2016, when presidential candidate Hillary Clinton denounced the Alt Right in a long speech, thus indirectly boosting public interest in the topic, Angela Merkel spoke to the topic of Querdenken in mid-December with rare emotion. Calling the movement “an attack on our entire way of life,” she said that “since the Enlightenment, Europe has chosen the path of building our view of the world on the basis of facts.” Confronting an “anti-factual” movement was very difficult, she said, “perhaps it will be a task for the psychologists.”

Merkel’s remarks were shared by Querdenker on social media with glee: her attempt to brand them with the stigma of mental illness confirmed their belief that the mainstream could only respond to their provocations with censorship and diagnosis. They have also matched her invocation of the Enlightenment with their own. A movement of skeptical medical practitioners calls itself “Doctors for Enlightenment.” Naturally, Immanuel Kant is a favorite reference. One group’s logo shows his wig and pigtail in the style of the brain and spinal cord. In his 1784 essay “What Is Enlightenment?” the philosopher wrote in the self-righteous tone that echoes in diagonal texts: “We find restrictions on freedom everywhere. But which restriction is harmful to enlightenment? Which restriction is innocent, and which advances enlightenment? I reply: the public use of one’s reason must be free at all times, and this alone can bring enlightenment to mankind.”

On what terrain is the struggle to be fought in the coming year? The Enlightenment is one candidate. Constitutional rights are another, as one journalist notes. The Cold War’s end is another recurring theme. Many protesters carry signs that make reference to 1989. “Merkel, this is your 1989.” “We are the people”—wir sind das Volk—is a common motif. Yet a notable feature of diagonalism is its rejection of political demands in the conventional sense. The impetus for diagonal movements ranges from the attempts of isolated individuals to form alternative social bonds—call it the “Bowling QAnon” thesis, to paraphrase Gabriel Winant—to the desire to work collectively to be left alone. In almost all cases, freedom is defined in the negative, reduced to individual license and shorn of any sense of mutual responsibility or solidarity.

Diagonalism could be seen as a fight over science. But both sides put open-ended investigation at the center of their identity. Public health officials acknowledge that science is done in public, knowledge of the virus is evolving, and forecasts are only ever provisional. Diagonalists respond that the truth is hidden by elite obfuscation and constant search is necessary in alternative fora and what Erik Davis calls the “DIY live action role playing game” that is the network of QAnon “drops,” chats, and clips.

Diagonalism could be seen as a fight over science. But both sides put open-ended investigation at the center of their identity.

There are three possible futures for diagonalism. In the first, the particular mobilizations of 2020 fade away. Confidence in the vaccine could grow with time and perhaps isolated demonstrations will soon be nothing more than occasional traffic disturbances—until, that is, a new variation of suspicion aimed at elites returns as climate plans roll out in the next months and years.

A second possibility is that votes of diagonalist malcontents are reaped by the far-right parties watching hungrily from the sidelines. The finding from the Basel study that made headlines was that a plurality of Querdenker had voted Green and Left in the last election, but an overwhelming majority said they would vote for far-right parties or new diagonalist parties in the next one.

A third path may see diagonalists launch another round of what sociologist Paolo Gerbaudo has called the “start-up parties”—modeled on tech companies and “characterized by rapid growth and high scalability, but also high mortality”—that have scrambled the European political landscape since the financial crisis. The aim would be to replicate the success of the Five Star Movement in Italy, which started from nothing to win the most seats in parliament just three and a half years later. Or the AfD, which became the official opposition four years from its own founding. Or the Brexit Party, which won the most votes in the UK European Parliament election in May 2019 after only four months of existence. Scrambling to capitalize on this moment of opportunity, Nigel Farage has already rebranded the Brexit Party as Reform UK and declared it an anti-lockdown party. The appearance of Farage on stage in Friedberg is evidence enough that all it takes is for one of the movement hustlers to find their moment. Even if Ballweg’s own mayoral run in Stuttgart, the failed launch of Widerstand2020, and the breakdown of Wir2020 into the “neo” party show dim prospects, venture capitalists, meme peddlers, and quack hippie healers all know one thing: you have to go through a lot of nags to get to a unicorn.

Storming Capitols of Power

Taking the tour of diagonalism abroad helps us reframe what is transpiring in the United States, where a combination of the second and third paths is already apparent. From early in the pandemic a slew of local and statewide “reopen” initiatives formed on social media and manifested themselves in anti-lockdown “freedom” protests led by small business owners whose cause has been trumpeted across conservative media. Although many such initiatives describe themselves as “neither Democrat nor Republican,” their conspiratorial ethos and anti-mask politics tack to the right of the Republicans, whom they are already threatening to primary by running new candidates of their own. Some of the participants have little or no history of supporting the GOP, coming instead from anti-vax, New Age, or other milieus.

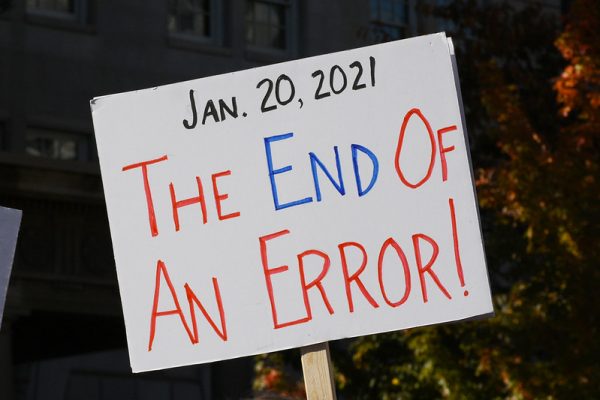

The electoral loss of the U.S. conspiracist-in-chief did not dam the river of falsehoods, but unsurprisingly galvanized movement hustlers and true believers to mobilize against the government, including the representatives of his own party. Commentators were quick to describe the “storming of the Capitol” on January 6 as a “breaking point” or a path “off the rails” of U.S. history. Yet the protesters’ ability to enter the building, in some cases with the aid of police, simply made visible what has long been brewing across the country, though now in a farcical and violent spectacle televised for a world audience. The far-right militants bearing weaponized gear and the self-documenting social media performers were gleeful about defaming the symbolic structure of government and denouncing Mike Pence’s confirmation of the Electoral College vote. But the class positioning and political intentions driving them were more diverse than the blanket coverage of the “Trump supporters” often suggested.

Indeed many elements of this allegedly all-American rightwing “insurrection” resonate with the diagonalism challenging countries around the world. Only in the days after the spectacle were the identities and stories of the most visible protesters revealed. Among the most eye-catching was the Bison Man from Arizona, also known as Jake “Q Shaman” Angeli, who moonlights as a “Behavioral Health Tech,” “Entrepreneur,” and YouTube Personality, according to his Parler profile, and who met Rudy Giuliani in suit and tie last year. By his side was a Maryland man whose company ID hung from his Navistar Direct Marketing lanyard. The Arkansas man photographed with his boots on Pelosi’s desk was an independent contractor who received pandemic-related support from the government himself. The Californian woman shot and killed in the Capitol was a “self-described libertarian” formerly in the Air Force who owned a struggling pool-supply company. Among the arrested were two men from the Chicago suburbs, a real estate agent and a CEO of a tech company focusing on data-driven marketing strategies. One Texas woman flew to the D.C. protests on a private plane.

It turns out that, despite all appearances and easy narratives, the rightwing protesters at the Capitol were not dominated by the so-called “left behind,” working-class deplorables whose image captured the mainstream imagination in 2017. Instead, the “fantasy putschism” of a QAnon-inflected protest was driven by an American brand of diagonalist hustlers and political entrepreneurs who self-fashion “outside the mainstream.” (Their actions may have been impotent and delusional but, as Richard Seymour notes, given certain conditions, delusional politics can win.) For some, a plane ticket and an upscale hotel reservation was an easy price to pay for a historic act of anti-government “resistance.” For others, Capitol-storming was just an unexpected gig among others in this gigified political economy.

Beyond the obvious spectacle of Trump’s Save America Rally, Giuliani’s ludicrous lawsuits alleging voter fraud, and attorney Lin Wood’s delusional tweets, recent protests—spanning the “reopen,” “stop the steal,” and other movements—have tapped into a kind of hustling that the right has perfected but by no means monopolizes for itself. Alex Jones may traffic in conspiracies to sell his dietary supplements (Super Male Vitality), but Gwyneth Paltrow can sell the very same supplement under another name (Sex Dust). The same goes for more savvy entrepreneurs of political outrage. The almost universal frustration of living in a COVID-19 world and the technological dynamics of social media have given form to a pandemic politics of capitalizable conspiracy, itself driven by the internal propulsion of incitement capitalism.

Trumpism has taken a hit but not a death blow. More diagonal currents are to come.

The events at the Capitol, and the intra-GOP divisions they revealed, were neither surprising nor singular. In their aftermath Trumpism has taken a hit, though not a death blow. It will outlive the presidency and remain more or less fixed to his person for the time being. But as in other countries, more diagonal currents will manifest from its residue in forms both radical and mundane. They will spur attacks from inside the Republican Party, while deepening its well-established line that the Democratic Party cannot legitimately hold power under a Biden presidency. Though led by entrepreneurial movement hustlers, the revolt of the Mittelstand will cut across class, race, and gender, with a diagonal tilt that leans hard right.

Where 2017 brought a reckoning with “populism,” then, 2021 may be dominated by discussions of diagonalism and conspiracy. Diagonal movements may bring bad news to established parties that are forced to navigate their disorienting energies with unpredictable effects. Pundits trying to make spider charts of rabbit holes may find themselves nostalgic for the days when their “populist” quarry had an easily identifiable name, a leader, and a face.

Boston Review is nonprofit and relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.