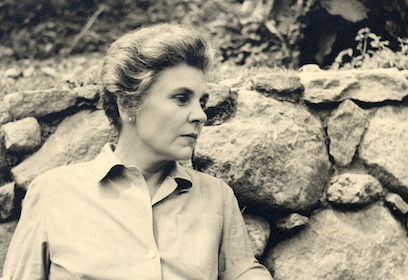

“The enormous power of reticence,” Octavio Paz wrote in 1977, “is the great lesson of the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop.” Many critics have echoed his praise since her death in 1979. “Bishop wrote delicately and elliptically,” Kathleen Spivack sums up in her 2012 memoir With Robert Lowell and His Circle. “What is most important is what is not said.”

Bishop’s reputed reserve has taken on new significance in light of personal correspondence discovered in 2009. When Bishop’s lover Alice Methfessel passed away, her heir found a locked box containing some of Bishop’s photographs and personal documents, including three remarkable letters she wrote to her psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Foster, in 1947. These letters were written at a crucial moment of Bishop’s career, and their discovery calls for a reassessment of her lyric development and legacy.

But their intensely private nature also raises questions about the ethics of archival reconnaissance. Scholar Lorrie Goldensohn, who first wrote of the discovery in January 2015, noted that the letters appear to have been carefully copied and preserved, perhaps by Bishop herself. The poet might have wished her oeuvre to be understood by a future generation alongside the secrets that, in her lifetime, she kept so carefully from view. Biography, when it resists hagiography, can’t help but adjust the light in which we assess a writer’s art. In Bishop’s case, the light limns astonishing shadows.

Bishop’s confessional peers made it easy for her to be miscast as a cautious dowager. In the late 1950s and ’60s, Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, John Berryman, and Anne Sexton, among others, boldly capitalized on the mid-century zeitgeist of domestic rebellion, writing poems that explored alcoholism and suicide, incest and infidelity, nuclear bombs and non-nuclear families—subjects that many Americans still regarded as taboo. By contrast, Bishop’s poems had a “Cordelia-like” quality, as Seamus Heaney described it: a sense that secrets were held in abeyance or dimly glossed as she rendered natural tableaux, ekphrastic meditations, and impersonal love poems, offering the reader startling moments—“the little that we get for free, / the little of our earthly trust”—without the full, wearying poignancy of what it took to arrive at them.

Bishop may have wanted her poems to be read by future generations in light of the secrets that, in life, she kept so carefully hidden.

Bishop indeed avoided what she termed “the tendency . . . to overdo the morbidity” that became common as confessionalism—or Robert Lowellism—came into vogue, spearheaded by her close friend and correspondent. Lowell’s Life Studies was published in 1959, offering portraits of his Beacon Hill childhood and bipolar episodes, his dread of Eisenhower, and his drunken nights with Delmore Schwartz and a taxidermied, rum-pickled duck. A few years later, Sexton, Lowell’s student, electrified the Boston poetry scene with her rock band and poems about suburban despair—thrilling audiences with her well-dressed rebelliousness, chthonic verse, and lean good looks. The poetry reading had not been so sexed up since W. H. Auden had read at Harvard in his scuffed-up bedroom slippers.

Bishop did not approve. Writing to Lowell from her expatriate residence in Brazil in 1960, she asserted that Sexton’s poems “had a bit too much romanticism and what I think of as the ‘our beautiful old silver’ school of female writing. . . . They have to make quite sure that the reader is not going to mis-place them socially, first.” Aware of how a poet might capitalize on gender, class, and family name, Bishop largely steered clear of autobiographical conceits and political critique in her first collection, North & South (1946). Later, as her poems engaged more directly with the plights and pleasures of the individual, they never showed up with a bassist, a menstrual cycle, or an aristocratic clan primed for desecration. Alongside the confessionals’ striptease, Bishop appeared reliably clothed.

Yet her poems are unflinchingly, unceasingly modern. With more subtlety and nuance than many of her peers, Bishop explored the marketplace of love and the homely accident of happiness; the arrogations of empire and ego; beauty’s unlikely appearance in the ugliness of a child’s death, an electric storm, or a blood-splattered armadillo; and art’s frail attempt to answer to life’s dinning disasters. A poet of broad sensibility and exacting technique, she excelled in classical forms, but she also riffed on blues songs and nursery rhymes, folk ballads and news broadcasts, building poetic structures of uncanny paradox, urbane surrealism, and figurative experiment. Few twentieth-century poets have been so proudly, possessively claimed by both new formalists and anti-lyricists, by the so-called establishment and the avant-garde.

It is ironic that Bishop should achieve the status of aesthetic alma mater of contemporary poetry. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1911, she lost her father in her infancy and her mother, Gertrude Bulmer, to psychiatric incarceration in 1916. The hospital file notes that Bulmer tried to hang herself with a sheet and to strangle Bishop’s grandmother; she spent the remaining eighteen years of her life in Nova Scotia Hospital, and Bishop never saw her after she was committed. The unearthed Foster letters fill in long-standing biographic lacunae regarding the extent of Bishop’s mourning for her mother and her other personal travails. They suggest that her reticence served as both a psychic and an aesthetic strategy. In the adage of Marianne Moore, Bishop’s mentor, the younger poet’s “omissions are not accidents.”

Bishop’s letters to her psychiatrist are newsy and notational. One begins with a friend surprising her “with a birthday cak[e] and some mimosa” and concludes with a hairstyling appointment before dinner with Randall Jarrell. But she also uses the letters as an extension of psychoanalysis, detailing a schoolgirl crush, for example, as well as a daring escape from a mixer party with “strange boys” that entailed hitchhiking and sleeping overnight in the Natick woods. The greater biographical significance of the letters lies in their revelation that Bishop suffered from incest and physical abuse as well as alcoholism and familial estrangement, subjects that many of her confessional peers explored publicly—often hyperbolically—in their poems. Although Bishop’s struggles with drink and parental loss have been well documented, these letters provide an aperture into her suffering, new information about her childhood traumas, and a compelling portrait of the solace she found in her psychiatrist’s understanding—a key to the poetics of recognition that marks her mature work.

Bishop’s epistolary persona is chatty and self-deprecating, even as she relates painful memories and concerns, including a growing dependency on drink. Alcoholic admissions punctuate her narrative: “while I was in my cups—kegs I should say”; “it’s taken three quarts of whiskey”; “I was so drunk I kept falling off my bicycle”; and “if only I didn’t feel I were that dreadful thing an ‘alcoholic.’” She traces her addiction back to the collegiate year in which her mother died and her unrequited love, the painter Margaret Miller, refused her. Bishop describes, too, her bouts of social anxiety (“I wanted to go but couldn’t damn fool that I am”) and her memory of a harrowing car accident in France that resulted in Miller’s arm being amputated. Poignantly, she recounts seeing in a lover’s expression at the moment of sexual climax, in “that mask of anguish we call joy,” the look of her late mother and “some connection with the word madness.” Bishop appears to have been haunted by her mother in some of the most private moments of her adult life.

In fits and starts, Bishop gradually relates the “long sad tale of Uncle George,” husband of her maternal aunt Maud Shepherdson. George began abusing Bishop when she was eight and continued well into her adolescence. He was an accountant for General Electric and a sadistic “storm trooper type” in his off hours; Bishop recalls instances in which he “lowered me by the hair over the second story verandah railing,” handled her sexually in a bathtub, and threatened to beat her without provocation. Altogether, the letters display an enabling trust between patient and doctor while providing new information about the poet’s hidden difficulties. In the gathering, concentric energy of these letters, Bishop shares confidences more intimate than what might be conveyed to a priest or a mother.

While these letters testify to a deep bond between analyst and analysand, they are also something of an ars poetica. Citing Edward Degas’s adage that “art doesn’t grow wider, it recapitulates,” Bishop credits Foster for helping her to “get over the fear of repetition.” She reports that she has begun to see each poem not as an “isolated event” but as part of “really all one long poem anyway” as “they go on into each other or over lap.” Bishop also situates the activity of writing poetry alongside dreaming and painting and emphasizes the genesis of her poems in fully formed, integral images.

Speaking of her poem “At the Fishhouses,” for example, she notes, “The day I saw this poem I was in Lockeport.” The poem is something seen, not just conceived. Bishop recounts awaking hungover, then taking a long bicycle ride “by way of punishment” to the ocean shore where she sat on the rocks, “cried for a while,” and visited with an Atlantic seal. That episode, she says, reanimated an earlier dream about a “wild & dark” storm in which she witnessed herself, “baby size,” feeding at Foster’s breast, a posture that she wryly rationalizes must be “a common dream about a woman analyst.” Bishop confides in Foster that this mammary imagery informs “At the Fishhouses,” in which the narrator describes knowledge as “drawn from the cold hard mouth / of the world, derived from the rocky breasts / forever.” Later on, addressing her psychiatrist as “Ruth,” Bishop indicates their shared vulnerability: “You once said that I wouldn’t think you had once been shy . . . . I should have been more empathic I think—I fel[t] right away that you had once . . . been frightfully shy and that was an other reason why I took to you.”

Shyness, in Bishop’s published work, often intimates the richness of a subject’s inner life, a capacity for ambivalence, or a retreat from socialized shame. Lovelorn narrators in her poems “One Art” and “Insomnia” and returned exiles in “The Prodigal” and “Crusoe in England” explore the anxiety of carrying secrets that have no place in the social order, that catalyze a “driving to the interior.” Yet shyness in Bishop’s poetry also frequently marks the empathic bond forged between self and other; to be shy in Bishop’s poetry is to accept the ostracon of self-knowledge and to relate to others on the basis of shared liability.

In her poem “In the Waiting Room,” Bishop depicts a child named Elizabeth waiting for her aunt at the dentist’s office. The six-year-old narrator reads an issue of National Geographic with pictures of naked African women. Intrigued by their “awful hanging breasts,” she finds herself “too shy to stop,” drawn onward by her curiosity about the scripts of gender and conscription of somatic suffering. This emboldened reticence, tied to an eros for knowledge without prohibition, informs Bishop’s mature style and the epiphanies in her Foster letters.

After her psychiatrist’s death in 1950, Bishop wrote to Moore that Foster had “certainly helped me more than anyone in the world.” In two years of treatment, Foster had reassured Bishop that she was “lucky to have survived” her childhood. Although analysis did not alleviate her alcoholism, Bishop was able to transmute her experiences into a poetics of psychological depth and acuity.

Not all mid-century poets were so lucky. In 1974, having spent her secrets in explicit poems and having been betrayed by a psychiatrist with whom she had an affair, Sexton embraced oblivion in her parked red Mustang, asphyxiating in her home garage. She joined the ranks of her generation’s other notorious poet-suicides, including Plath (1963) and Berryman (1972).

With Foster, Bishop had found a different way of navigating her troubled life in her art. Reading their correspondence illuminates not only the secrets Bishop kept hidden but also the intimate recognition and humane knowledge embodied in her poetry and prose.