Porn Work: Sex, Labor, and Late Capitalism

Heather Berg

The University of North Carolina Press, $22.95 (paper)

Sex, Society, and the Making of Pornography: The Pornographic Object of Knowledge

Jeffrey Escoffier

Rutgers University Press, $27.95 (paper)

Tumblr Porn (Remember the Internet, vol. 1)

Ana Valens

Instar Books, $16 (paper)

The Pornification of America: How Raunch Culture Is Ruining Our Society

Bernadette Barton

NYU Press, $24.95 (cloth)

Pornography is messy, and that’s if it’s good. “Pornography” is also messy to define. The line between erotica and obscenity is always moving (and historically classist), and something that gets you off might seem quaint or silly to me. Must pornography be a “sexually explicit” representation of flesh-and-blood humans, or might cartoons, computer animations, or even just text sometimes suffice? And if, historically, the legal difference between prostitution and pornography was the presence of a camera, the emergence of social media platforms where performers sell video content direct to consumers—often fulfilling customers’ requests—seems, at last, to dissolve all distinctions between sex work and porn work. This is a welcome development, should it legitimize and humanize a wider range of erotic labor.

The difficulty with defining pornography—and the political and litigation wars waged over its meaning—makes it unsurprising that four recent books about pornography have wildly different methods, perspectives, and objects of analysis.

Heather Berg’s Porn Work focuses on the labor conditions of present-day, flesh-and-blood women performers in hetero porn, although she also interviews men performers as well as directors, managers, and producers. Indeed, an important takeaway of Berg’s book is that, more and more, the same people fill the positions of performer, director, and producer, reconfiguring workers’ solidarity.

The essays collected in Jeffrey Escoffier’s Sex, Society and the Making of Pornography, on the other hand, mainly investigate the representational styles and labor practices that traversed gay male pornography from the 1970s until the early 2000s.

Ana Valens’s Tumblr Porn, a juicy little afternoon read, differs significantly from both Berg’s and Escoffier’s academic monographs. Valens recalls with yearning yet critical affection the queer, feminist, and kinky erotic imagery that circulated on the social media platform Tumblr before it banned adult content.

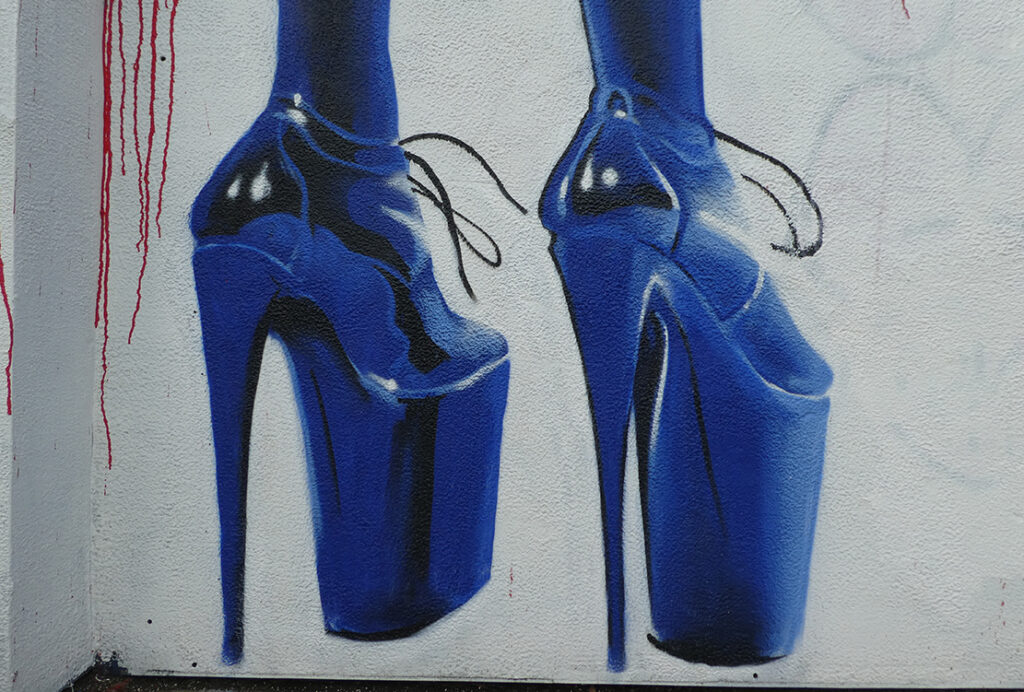

Finally, in Bernadette Barton’s The Pornification of America, porn is, well, everywhere. Since the mid 1990s, writes Barton, with the rise of the Internet and then social media, “raunch culture” has saturated every corner of our lives, as we are bombarded with images, feeds, advertisement, films, shows, political campaigns, and porn that increasingly feature sexualized, sexist, and misogynistic depictions of girls and women. Barton uses “raunch culture” as a shorthand to describe the “pornification of everything,” but what she really means is the “pornification” of young women, how their appearance in social life and on social media is conditioned on explicitness and exposure. (Walking past the line for a New Haven nightclub the other night, I couldn’t help noticing how naked and uncomfortable the girls looked in pleather crop tops and immobilizing heels, and how armored and assured the boys seemed in oversize T-shirts and high-tops.)

And yet there is a common denominator to these four books: all emphasize that contradiction is at the very core of pornography and its political economy. Anyone unfamiliar with how scholars write about porn—which is to say the billions who prefer getting off to porn rather than reading about it—might greet that thesis with skeptism because contradiction presupposes complexity. What could be any less contradictory, any less complex, than watching people fuck on your screen? Has there even been a more undialectic hot take than Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart’s famous definition of “hard core pornography,” “I know it when I see it”? (The second half of Justice Stewart’s sentence is less well-known but twice as important: “I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that”; in fact, then, Justice Stewart’s definition is as dialectic as it is meaningless, hence contradictory after all.)

In the remainder of this essay, I will reconstruct these authors’ engagements with pornography’s contradictions, or “porno dialectics” as Berg terms them, to consider when pornography—whether as labor practice or as representational form—might portend erotic flourishing, when it might naturalize subordination, and when porn might just be uninspired or flaccid.

In Porn Work, Berg wants porn audiences (and porn scholars) to consider what it is like to be a worker when your job is having sex on screen. Among the four authors under review, Berg most explicitly embraces the idiom of contradiction. She hones in on how porn work is both exceptional but excruciatingly ordinary, the most insecure of gig economies but also rife with possibilities for appropriating the means of production (at this point, just “your body, a smartphone, a web connection”).

The contradiction that foremost occupies Berg is this: on the one hand, sex workers fight for the right to have their labor classified as legitimate work, and “Sex Work Is Work” is the political battle cry they wield against enemies on both sides (anti-porn feminists and family-values conservatives). On the other hand, work sucks. It often sucks to be a sex worker, specifically, but more generally it sucks that work, any work, is necessary for survival. So the big question for Berg—and for the performers and producers she interviews—is whether the pleasures and innovations of porn work offer insight into what a post-work world might look like, even as capital gobbles up everything it can make profitable, including pornography.

Many of Berg’s interviewees started working in porn to escape the drudgery and uncompromising time demands of “straight” work, only to find that being successful in porn required endless hours of unpaid labor in the form of social media curation, self-promotion, and advertising. For Berg, then, the idea of some kind of fabled work–life balance distracts us from asking the more apt question: “What does it feel like when life is so thoroughly put to work?”

The contradictions accumulate from here. Contrary to the stereotype, porn does not pay well for most performers, so nearly all of them hustle in porn-adjacent industries such as dancing and escorting. But the hustle dampens porn wages, since producers assume their performers hustle. Meanwhile, the ease with which porn actors can become porn producers and directors—often out of financial necessity—undercuts the potential for class solidarity within an industry that, counterintuitively, denigrates sex work and sex workers.

Berg’s interviewees appreciate porn work for the erotic and nonerotic pleasures it sometimes provides, but they are wary of how “pleasure” and “authenticity” are extractive demands made by management. The incitement to be “real”—to act like you like it—emotionally overtaxes workers, while the presumption that performing porn is ipso facto pleasurable justifies underpaying them (this is especially true, Berg notes, for straight men and for Black women, both stereotyped as always horny and so dtf). In self-described feminist porn, this demand for “authenticity” is acute, despite the ostensibly good politics of producing porn by and for women, nonbinary folks, and those with a wider range of body types. That feminist porn typically also pays less makes its claim to the high moral ground in the porn industry yet one more contradiction.

To combat the precarity of their labor conditions, porn actors have come up with some ingenious solutions. For example, porn companies now rarely provide actors with a wardrobe for shoots, so they have to provide their own. In response, they will invite their online fans to buy and mail them underwear or other lingerie items to be featured in a scene. And then—this is the seed of revolution, and I don’t think I’m kidding—the actor will auction off their used garments to the highest bidder. So porn performers transform porn production austerity into a profitable enterprise.

Berg’s Porn Work wants to scale this story up, emblematizing the ways porn workers “hack their industries” to imagine life without work, or at least with a lot less of it. Berg points out that, contra famed feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, porn performers and erotic content creators have often wrested far more control of their time and labor conditions than, say, adjunct professors. This is in part because of political organizing, but in part because of supply and demand: “there are more contingent academics than there are people who can successfully carry out a double anal scene.” Back in the day, MacKinnon too recognized that all work under capitalism sucks; now, and with embarrassing myopia, she claims only sex work sucks.

The core contradiction running through Escoffier’s collection of essays in Sex, Society, and the Making of Pornography is how gay pornography “affirm[s] gay identity” but does so by suturing gay desire to allegedly straight men—whether in scenes of “straight-acting” guys fucking each other, or actors who fuck guys on film but have wives or girlfriends in “real life.”

In one of the book’s essays, Escoffier surveys the 1970s films of two major gay porn directors, Jack Deveau and Joe Gage, observing how the films stage “homosexual desire among men with no gay identity.” Compared to present-day gay porn films, the partners in these films were less bound to strict roles of top and bottom, and the sex acts are not so determinedly sequenced as they are in more recent films, in which the action typically (although by no means always) builds to anal sex and everything else is foreplay.

Escoffier astutely diagnoses the interplay between porn and culture when he writes that “versatility represented the politically fashionable style of fucking.” Escoffier meditates on pornography as an underexamined cultural artifact, even as he is generally cautious about reading gay sexuality out of gay pornography, thematizing instead “historically different aspects of sex and attitudes toward it.” He suggests that gay porn’s post-Stonewall documentary style initiates viewers into a “whole geography of sexual encounters,” mainly sites for public or quasi-public sex in Manhattan and Fire Island.

Escoffier explains too that we learn from porn, and that the now-typical sequence of events in gay porn (oral, rimming, anal, ejaculation)—along with the rigidity of top and bottom roles—may instruct viewers in how to perform their own sexuality. Although the educative power of porn can be restrictive, it can also be expansive. A key point for Escoffier (and for Valens in Tumblr Porn) is that porn’s supply creates its own demand, restructuring and expanding viewers’ desires: someone might not be into or even know about a particular kink until they see it. And porn is obliged to endlessly introduce new content since viewers bore easily. Porn renovates itself to fan the desires it ignites and then, by overexposure, extinguishes. This can be a fabulous, sensual phenomenon, wherein people discover new pleasure and sensations with themselves, their partners, and their screens—or, as Barton notes in The Pornification of America, it can be gross: with each reinvention, porn gets nastier, more misogynistic, and more violent.

Escoffier never fully answers the question of why so much gay porn eroticizes masculinity, muscularity, and hetero manhood, but he flirts with the obvious if oversimplified answer: if gayness has been historically associated with inversion and femininity, and femininity, in men especially, is scorned, then dude-bro-next-door-type porn (think the popular gay porn site Sean Cody, which specializes in wholesome, straight-seeming college-age jocks) sells the fantasy that gay sex does not upend what it means to be a man. (Pedantically and not incidentally, I suspect that gay men who identify exclusively as tops just lack feminist consciousness.)

There is no greater embodiment of contradiction, at least for Escoffier, than the ever-present figure of the gay-for-pay, a straight-identified man who performs gay sex acts for money (in porn, but also sometimes as a dancer or escort). Escoffier is enthralled by this character, a puzzle of great challenge and consequence. How are presumptively heterosexual men able “to sustain a credible sexual performance, to have erections, and to produce orgasms” when they have sex with other men, Escoffier asks in several of the book’s essays. To answer the bedeviling question, Escoffier leans heavily on the sociological concept of “sexual scripts” elaborated by John Gagnon and William Simon: reductively, that sexuality and sexual subjectivity are not biologically determined but organized by cultural contexts, interpersonal relationships, and intrapsychic developments.

I found this appeal to sexual scripting less illuminating than Escoffier hopes. On Escoffier’s own account, many actors in gay porn identify neither as “gay” nor “straight.” He notices that many simply refer to themselves as “sexual” or avoid questions of identification. In 2019, after several go-go boys at a gay club in New Orleans hit on both me and my female cousin, I asked one lithe, long-haired dancer if he and his coworkers were gay. “We’re millennials,” he quipped, “we don’t care.” The many “not gay” ways that men-who-have-sex-with-men choose to identify themselves is a rich area for inquiry, underexplained by Escoffier’s use of either “situational homosexuality” or “sexual scripting.” More simply, Escoffier vastly underestimates the power of erectile enhancement medications (as anyone who has taken a “dick pill” and then ridden a bus can attest).

Escoffier’s question boils down to how gays-for-pay succeed on the job. Berg’s question is the better one: not, How do men have sex with people they aren’t aroused by? but rather, How do porn workers of all genders stay aroused when shoots last for several hours, when hurry-up-and-wait is an occupational necessity, when scenes are physically taxing and painful, and when production staff members are crowding the set?

Berg’s answer is surprisingly touching. Most performers, she learns, “value screen partners with whom they share collegiality or even friendship rather than those with whom they would choose unpaid sex off set.” Getting along with and respecting your coworkers might be the better explanatory variable for a successful sex scene than crafting a “sexual script” for yourself that culminates in tumescence. Berg also intimates that Xanax and other “antianxiety aids” “enable . . . functionality.” There is clearly a book to be written about the coterie of medications and illicit substances that eroticize, or just make feasible, sex on screen, sex for money, and sex for money on screen. Of course, Berg would reply that the mania and misery of late capitalism means workers in all kinds of employment vectors medicate to get by.

“Tumblr is a site of contradictions,” writes Valens in Tumblr Porn, a eulogy for the social media site which still exists but is now sexless, lifeless, and all but worthless (the company’s valuation, well, tumbled after its 2018 adult-content ban). But Tumblr Porn is also a call to arms for queers and other sex radicals to create and defend user-generated sexual content as a source of community and coalition-building, as a countermeasure to the stifling norms of mainstream porn, and as a wellspring of funky, weird eroticism.

Valens time travels with her readers to the hot queer universe of pre-ban Tumblr, when the platform made space for queerness not just as a social identity but a sexual one too. For Valens, her favorite users’ “content normalized not just the idea of trans women as sexually desirable, but also penises as—in and of themselves—vessels for trans sapphic desire.” (If for no other reason, read Tumblr Porn for Valens’s shimmering phrases. How could I not quote “penises as … vessels for trans sapphic desire”?)

If, for Berg, feminist porn is hypocritical in its labor practices and if, for Barton, feminist porn is so negligible in the universe of porn as to be an ideological distraction from, or even cushion for, misogyny, for Valens, the feminist and feminist-adjacent porn she discovered on Tumblr was a lifeline, a portal to an erotic world that affirmed all kinds of marginal sexual identities and fantasies. I learned about giantess and yiff porn from Valens, for example. Valens reveres the trans and female erotic content creators she followed on Tumblr. “Growing up,” shares Valens, “I assumed that sex was something done to women by men. I never knew that women could be just as thirsty as men and could solicit sexual interaction just for the sake of it.”

So why then is Tumblr a site of contradiction? For one, follows and reblogs (the Tumblr equivalent of Twitter’s retweets) meant all kinds of kooky, not-grossly-misogynistic porn went viral and was beamed into thousands if not millions of eyeballs. But virality also meant piracy, and so erotic content producers and performers were robbed of their profits. Virality and piracy also fed into the prevailing Internet vibe that “all porn should be free,” which rehashes the harmful stereotype that sex work is not work.

Another of Tumblr’s contradictions was that, unlike Facebook, it permitted user anonymity—even as it encouraged users to use that anonymity to share their deepest, often taboo desires with the world. “To see someone’s Tumblr,” Valens writes, “was, in essence, to peek into their soul,” even if you had no idea to whom that soul belonged.

But the most painful of Tumblr’s contradictions—and one that will not surprise you if you’ve ever used the Internet—was that even as the site facilitated queer social and sexual connectivity, the very features that made Tumblr so enriching (anonymity, reblogging, easy commenting) also made it ripe for meanness, callouts, cancelling, and virulent racism and misogyny.

Tumblr sowed the seeds of its desuetude even before its 2018 NSFW ban, Valens argues. She takes aim, in particular, at Tumblr users who participated in the practice of tagging all political movements, social norms, trending phrases, and porn they disliked with the word “#anti”. This loose community of dislikers grew into a community of cancellers, an anti culture that had a “destructive impact on Tumblr’s adult, queer, and fandom side.”

At first blush, the Tumblr anti culture that Valens denounces could register as a remedy for the “raunch culture” that Barton takes to be destroying humanity. After all, as Valens points out, the Tumblr antis went after porn and erotic content creators, successfully lobbying to ban users’ blogs. Valens recounts how one user’s account was shut down because her “sexual fanart” allegedly depicted minors (for material to be deemed child pornography under U.S. law, an actual child needs to have been filmed or photographed; this legal definition has little if any bearing on what social media platforms decide to ban, though). But that wasn’t the end of it. The antis then went after Valens herself for publishing an article about how the antis came after the artist! Here we witness a cancel metaculture reminiscent of the Title IX charges brough against media scholar Laura Kipnis for criticizing Title IX.

Were the antis righteously battling the sex and sexualization that Barton warns is ruining the United States? Can raunch culture be cancelled?

These are the wrong questions, in part because anti culture is cut from the same cloth as raunch itself. Anti-ness and raunch operate by flattening out or instrumentalizing others into objects, deracinating sexuality into obscenity and libelously trashing a diversity of online erotic content and online sex work as damaging, usually to minors. This is why the NSFW Tumblr ban, like FOSTA-SESTA—a set of federal laws passed in 2018 ostensibly to curb sex trafficking—do absolutely nothing to attenuate raunch culture and in fact aggravate it.

The Tumblr ban, precipitated by antis’ aggression costumed as victimization, erased or displaced an already tiny universe of feminist, queer, trans, furry, kinky, or otherwise-creative pornography and erotic art. Of course, the Internet and social media are as pornographic as they ever were, but now that porn is just more misogynistic, less diverse, and less interesting.

FOSTA-SESTA, meanwhile, comes under scathing and convincing criticism from both Berg and Valens, who decry the laws for endangering sex workers under the guise of helping them. Fearing they might be held liable for sex trafficking, sites such as Tumblr, Craigslist, Xtube, Pornhub, Twitter, and, most recently OnlyFans (although it has since reversed course) have preemptively censored escort advertisements and various forms of sexual content, or been forced to by various kinds of corporate censorship (such as when Visa and Mastercard stopped processing payments for Pornhub).

As Valens point out, determining what even counts as “sexual content” is no easy task, although content produced by kinky people, queers, and sex workers (particularly those of color) is always hit hardest by such purges. The cascade of self-censorship by social media platforms that has followed the passage of FOSTA-SESTA has cruelly coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made sex work more difficult and digital sexual content more necessary to the mental health of quarantined people everywhere.

Have any children been saved from pimps and pedophiles by FOSTA-SESTA? Unlikely. Instead, sex workers are made more precarious, their revenue sources kiboshed, and they are forced once again to depend on pimps, third-party managers, and street work. And so the NSFW Tumblr ban that Valens laments probably did little but wipe out the erotic content posted by queer and trans artists and sex workers.

If we cannot wipe away sexually explicit imagery without trammeling upon the lives, lusts, and labors of queers and sex workers, might we be more successful if we were more surgical, censoring or at least condemning imagery that is not just sexually explicit but also sexist? And in a sex-unequal world, how might we tell the difference? In The Pornification of America: How Raunch Culture Is Ruining Our Society, Barton maintains that what is sexy can be pried apart from what is sexist, although her thesis—that “pornification” poisons our lives, relationships, and communities—relies on presuming we can’t.

Granted, a title like Barton’s does not lead one to expect an exercise in dialectic or even particularly subtle thinking. A society “ruined” by x, y, or z hardly leaves room for any contradictions contained within the ruinous variable (“pornification”). And this is a shame, because Barton’s polemic is worthy of being read, especially by those least likely to be drawn in by its title: namely, people like me, those who have long thought of themselves as comfortably camped on the sex-positive side of whatever fight we are fighting.

Barton argues that something counterintuitive and grave is happening: as our culture becomes increasingly sexualized, it is actually becoming less sex-positive. In other words, the more unsolicited dick pics in cyber circulation, the less pleasure there is for everyone, especially women and nonbinary people. And the calculation crunches out the same, for Barton, if we substitute unsolicited dick pics with risqué selfies on Instagram or ads in which women in G-strings sell water coolers or hamburgers.

Whereas Berg and Escoffier went pictureless—both wishing to steer us from porn as representation to porn as documentation of laboring bodies—Barton pummels readers with images drawn from the “limitless feed of sexist memes” she excavates from raunch culture. These include numerous advertisements and stills from films and music videos that depict, with little variation, girls and women nearly naked and, perhaps more importantly, passively configured and constricted in such a way that each could be reasonably captioned, Put your penis in or on me.

An unembarrassed superhero-flick dork, I (and many others) have been miffed by the pornification of the still-too-few women heroes and villains. Why would the otherwise savvy Wonder Woman, Lara Croft, or Harley Quinn wear so little clothing to fight their heavily armed enemies? Citing anti-porn scholar Gail Dines, Barton avers “women have two choices in porn nation: to be fuckable or invisible.” The representational repertoire is broader than these options surely, but the observation is worth pausing over as you watch the next action film or scroll through your Insta. By contrast, the images Valens’s book reproduces from Tumblr offer something like sex-positive nostalgia, cartoons of humans, furries, and anthropomorphized animals of all shapes, genders, and sizes pleasuring themselves and others.

When Barton clarifies that “raunch culture matters because it is sexist, not because it is sexy,” one wonders whether instead of dubbing her nemesis “raunch culture,” she would have been better served by something more precise (although less catchy) like “tiringly gendered eroticized subordination.” Indeed, after documenting, depicting, and decrying raunch culture, this imprecision leads Barton to overreach. Her two most ambitious claims are, first, that “internet pornography ruins sex” and, second, that “raunch culture aided and abetted Trump’s win. . . . I would go so far to say that raunch culture is the glue that holds his administration together.”

Barton provides scant evidence to substantiate either argument. Her interviewees parrot Barton’s foregone conclusion (for example, “Kayla believes that ‘porn and video games have destroyed an entire generation of men’”) but that does not make them true. As for the election of Donald Trump, what Barton intends is that the mainstreaming and casualization of sexist, violent imagery normalized Trump’s misogyny into a nonevent for voters. But blaming porn for Trump is easy and insufficient.

This combination of grandiose assertions and paltry proof—as Barton concedes, “social science data examining the effects of pornography . . . tell a varied story”—recalls the sky-is-falling claims that energized yesteryear’s porn wars and soured many would-be allies to feminism and many feminists to even the mildest critiques of porn. Anti-porn crusader Robin Morgan’s “Pornography is the theory and rape is the practice,” for example, is a jaw-dropper of a maxim, but its purposeful oblivion to non-rapists’ enjoyment of porn—and its breezy spotlighting of sexual explicitness over explicit sexism—makes it exactly the kind of directive that causes otherwise convincible folks to bristle at the word “feminism.”

When Barton bemoans that, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, “traffic to Pornhub increased 10-20%,” Barton refuses the question of whether increased traffic to porn sites is itself a problem or rather if the problem (if there is one) is what people find there. Recall that the only good thing about March 2020 was masturbation.

But it would be a shame if readers were so thrown by Barton’s rhetoric that they missed her more measured and incisive charges: for example, that pornography’s content is “so relentlessly sexist, and weirdly violent” that it mostly absents “women’s sexual pleasure”; that Internet pornography has become exponentially more violent over time, so that “mainstream” porn now just is violent porn; that branding any and all criticisms of misogynistic porn as “prudish” or “sex-negative” is a means of maintaining patriarchy; and the sage advice to depersonalize criticisms of raunch culture so that our crosshairs are not aimed at, say, our friend’s predilection for racist porn but rather at the widespread availability of racist porn (and racist porn’s superior pay scale).

Barton is insightful too about the shortcomings of a culture that upholds consent as the best (and too often only) way for girls and everyone else to articulate their feelings about sex, sexual desire, and sexual attention. Barton interviews a woman named Alexis who, while competing on her high school debate team, received a torrent of unsolicited dick pics and jerk-off videos from her teammates and other boys. Alexis explains to Barton that she never told her mother about the pics and vids, but that if she had, she is sure her mom, in an effort to be sex-positive, would have encouraged her “not to do anything I don’t want, and to save it for someone you care about.” Barton wisely observers that, so doing, Alexis shifted the discussion toward “consent and pleasure, important topics absolutely, but not the first to tackle when one’s child . . . is being flashed in the park, or sent unasked-for videos of boys masturbating.” Barton advises Alexis, “You don’t need to shroud your experience in the language of consent and sexual education.” In this short anecdote, Barton captures something right and hard to confront: that sex positivity can mystify the pervasiveness and normalization of rape culture.

Barton’s and Berg’s books mostly speak past each other. Barton’s is a polemic against sexist representation, while Berg’s presupposes that anti-porn polemics overemphasize representation, take too little interest in labor conditions, and romanticize noncommercial heterosexuality. Because of this, they are unlikely to see themselves as allies in their shared critique of our culture’s infatuation with “enthusiastic consent” as a panacea for all of sex’s ills and injuries. Berg delectably describes enthusiastic consent as “whorephobic”: porn performers have a lot of sex they “want” for financial purposes but do not “desire” for erotic ones. How many people enthusiastically consent to their shitty jobs, anyway? But what holds these two consent critiques together, Berg’s and Barton’s, is the shared recognition that refurbishing consent transforms neither the political economy of sex nor the cultural norms of gender.

That the United States seems unable to regulate erotic labor well, and in fact does so terribly, likely intimates why Barton’s antidote to raunch culture is, in short, feminist consciousness-raising and comprehensive sex education rather than state surveillance; why Valens’s solution is for queers and fellow travelers to seize the means of digital production; and why Berg and those she interviews advance a guaranteed annual income, universal health care, and publicly funded STI screening. Because Escoffier does not seriously countenance the racism of gay porn, the misogyny (and racism) of straight porn, or the violence elemental to most porn, the main problem for him to solve, meanwhile, is how to reinflame the “porn star’s sexual heat” after his halcyon days (his answer: do condomless porn or get kinky).

It would be easy to miss that all four authors, of different and sometimes opposing political positions, share another commitment besides their embrace of contradiction: their agreement, explicit or implicit, that state and corporate censorship will not solve but only exacerbate the social ills they diagnose. By extinguishing erotic diversity and marginalizing sex workers and sexual minorities, state and knee-jerk corporate censorship do raunch culture’s dirty work by knocking out its competition.

And yet our response to phenomena such as revenge porn and deep fakes—what we might think of as jagged outcroppings of raunch culture—cannot be libertarianism either. In the middle of Tumblr Porn, Valens argues that legislators going after sites like Craigslist and Backpage for the alleged bad behavior of their users is like holding park rangers accountable for the bad behavior of park visitors. But the analogy teaches the opposite lesson Valens wishes to impart: if a park visitor sexually harasses or assaults another visitor over and over in front of a do-nothing park ranger, then we likely want to hold the ranger (or at least the public authority) accountable. See Facebook and the past two presidential elections. So the progressive answer should not be all regulatory oversight is bad, but instead we must consider, queerly and collectively, which forms of oversight enhance erotic flourishing and which quash it.