On Saturday, I checked my phone and saw that we’d heard from my uncle, currently a political prisoner in India. “I’m alright,” he said. But he wasn’t alright. His voice was weak and feeble, and his words, disjointed, slipped into Hindi instead of his beloved Telugu. For over six decades, Varavara Rao, the revolutionary poet, captivated generations with his critical poetry and prose. That he was anything less than articulate, let alone incoherent, was a gut punch. The goal of Narendra Modi’s administration has been to silence those like my uncle. Had they succeeded?

In one of the many conspiracy cases lodged against Rao over the decades, the state attempted to demonstrate that all the actions of revolutionary movements were a direct consequence of the poems, speeches, and writings of radical writers.

There are many ways to describe Varavara Rao. He’s a teacher, a poet, an activist, known to many simply as VV. To the Indian government, he’s a rebel and a threat, an “anti-national.” It is, in fact, possible to sketch independent India’s history simply by the dates of fabricated cases brought against him by the Indian state: over the last forty-five years, there have been twenty-five, for which he has spent eight years in prison, awaiting trials that would eventually acquit him. His landmark contributions to the discipline of Marxist literary criticism as a left-wing intellectual and his fearless opposition to religious orthodoxy, caste discrimination, and neoliberal development earned him the love of those invisible to the state, and, unsurprisingly, the wrath of landlords, bureaucrats, and police forces alike. Beginning with the rural rebellions for land rights in the 1960s—and continuing through the severe repression that followed—he unflinchingly stood by disenfranchised tribal communities, going on, at the start of the millennium, to serve as an emissary in peace negotiations between the Andhra Pradesh government and the Naxalites.

But to me, he’s just Bapu, a term of endearment in Telangana for “father.” By relation, he is my maternal uncle. But for generations, for nieces and nephews and grandnieces and grandnephews, he’s always been Bapu and us, all of us, his grandchildren. Through most of the first decade of the 2000s, we—my sisters, my mother, and her sisters—would spend many summer days at my uncle’s house in Malakpet in Hyderabad, the city I grew up in. His living room welcomed a rotating cast of visitors while my aunt, Aamma (a quirky elongation of “amma,” mother), unfailingly offered them chai. That part of my childhood coincided with a selective rising tide in India; many families such as mine experienced upward mobility and made frequent moves into increasingly elite neighborhoods. Bapu and Aamma’s unchanged apartment in humble and overwhelming Malakpet gave their presence in my childhood a timeless quality.

For us children, make-believe turned neighboring flats into enemy castles, the front hallway an open field, and the sturdy staircase walls, covered in dust and grime, ideal hiding spots. When it was time to go inside for mangoes, the adults talked with immediacy about distant places such as Palestine and Cuba, or Warangal and Chattisgarh, closer yet also unfamiliar. Someone had been harassed by the village headman, beaten up by upper caste groups, and needed legal help. Someone had been killed—“an encounter,” they said. (I would later learn the term referred to extrajudicial killings by the police.) The conversation shifted. Everyone had read something new. Precocious voices eager to share. A feminist poem, translated from Urdu, in last week’s paper. A new book on the FARC in Colombia. A friend’s recommendation. The exchanges never ceased, as the family I knew drank in each other’s warmth, hungry for raised voices and raucous laughter.

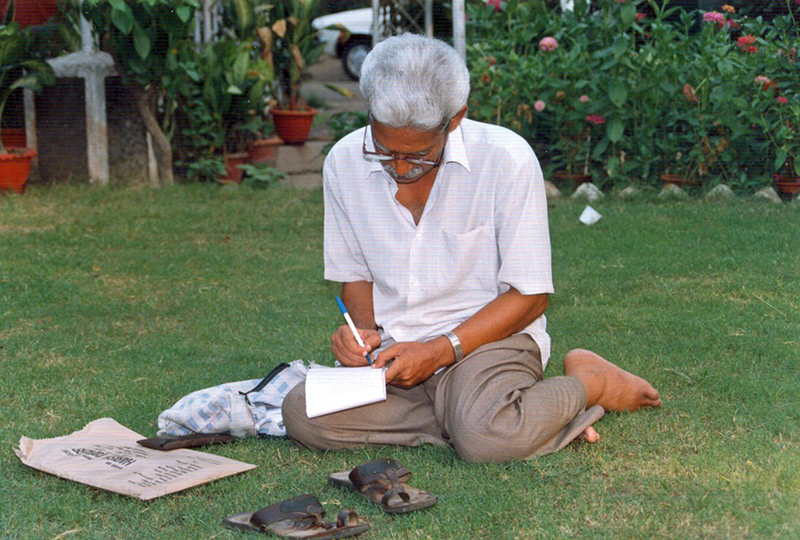

My entire life, Bapu looked exactly the same. A crisp white shirt, or sometimes light blue, a pen resting in the pocket, and a head full of silver hair; he always had a smile playing on his lips. When he greeted us at the door, it was with a hug. “Bagunnava, bidda?” (Are you well, my daughter?) he would ask my mother. At the time, this was rare; men and women did not typically hug each other. Later, I came to appreciate it as one of the many things that I did not have to unlearn—I had already been taught to love openly, freely, and joyfully.

Bapu and Aamma’s 1990 move to Hyderabad was a forced one. At the conference of the Andhra Pradesh Raithu Cooli Sangham that year, a peasants’ movement demanding “land to the tiller,” Bapu had addressed a crowd of over 1.2 million. This drew the fury of the state police, who, five years earlier, in 1985, had assassinated Bapu’s comrade, Dr. A. Ramanathan and implicitly declared their intention to target Bapu as well. Under ever-increasing threats, Bapu and Aamma left their beloved Warangal, as the newly elected Congress government followed in the footsteps of the earlier Telugu Desam Party, stifling left-wing movements across the state. This all happened a few years before I was born, but I can picture it vividly. A black-and-white sketch of Dr. Ramanthan’s room as the police left it—his doctor’s chair knocked over—hung on Bapu’s living room wall throughout my childhood. This story, like many others, became legible to me only over time.

What I experienced in Bapu and Aamma’s house, amidst an eternal supply of chai, is what I’ve now come to recognize as an education. A grad school classmate from the United States once asked me where my politicization began. Swiftly I had answered, “At home, with my parents.” “And theirs?” It was Bapu. Not only for my parents, but for generations of people since he began writing as a young man in 1957. Watching him advocate fearlessly and be persecuted by government after government, multitudes of activists began to demand the protection of civil rights for the most marginalized, at a time when the zeitgeist tended toward the shining narrative of a rising India—of hydroelectric dams built over tribal lands and industrial zones replacing communities.

So, when my parents reminisced about the Telangana movement, or the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, their stories were never meant to be remarkable; they were commonplace in a generation begotten by Varavara Rao. And like him, they too were teaching their children the humble notion that Bapu’s battles ought to be their own. That if they could be angry about the same things, their anger too would find its place in political action.

“In what discourse / Can we converse / With the heartless?”

If Bapu found imprisonment difficult, we never knew it. He never wanted us to. Witnessing his life in this manner, in and out of prison, was to learn how the application of law could itself be illegal and, in that same instance, understand how to imagine resistance. Persecution was so commonplace that we would often find him calmly waiting, with a packed “jail bag,” having been tipped off about a forthcoming arrest.

So, when the police descended upon Bapu’s house, and the houses of his three daughters, in August 2018, there was no way to predict that this time would be different. There’s an arrest warrant, the police had said, or maybe it was a letter? In Marathi. But Bapu didn’t speak Marathi. Someone said that it was about a plot to assassinate Modi. “Where’s your laptop?” the police kept asking, certain in the belief that, surely, Bapu had not written thousands of pages of radical literature by hand. He had.

When I got the news of the raid, I was at an airport boarding a flight to Hyderabad, and unable to access any information for the next many hours. Only after I landed did I hear the details of the arrest: he wasn’t alone and had apparently been arrested along with some of the biggest names of Delhi’s and Mumbai’s left circles, Sudha Bharadwaj, Gautam Navlakha, Vernon Gonsalves, and so on. I breathed easier, feeling that, surely, Bapu would come out of this. The police accused him of “waging war against the State,” among other offenses, punishable by death or imprisonment for life. Almost two years later, he has not yet been formally charged; this is not only cruel, but blatantly unconstitutional.

When Bapu was taken to prison, newspapers everywhere carried a photograph of him leaving the emergency ward of the Gandhi hospital in Hyderabad, a secret route chosen by the police to avoid the media on his way to jail. Flanked by a few policemen, he had his fist in the air and a smile on his lips. Someone had managed to secretly photograph him from the crowd. He looked radiant, as always. I read last week that the photographer was Ravi, who, over a long career, captured historic moments and had recently died. It was strange to read about him, to feel the loss of a man I had never met but who had given me something I so treasured.

• • •

Campaigns for Bapu’s release began in no time. The college where he’d taught for thirty years, Warangal’s CKM, stood in solidarity. Abroad, the Bhima Koregaon case, as it came to be known, became infamous, and the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International all condemned the arrests. “The nine human rights defenders currently in jail and others implicated in this case are being targeted due to their work in the defence of human rights,” read the statement by Frontline Defenders. Over a hundred global intellectuals—the likes of Noam Chomsky, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Judith Butler, and Bruno Latour—called for his release, noting that over the decades, “the Indian state has been trying to silence his voice by implicating him in many phony cases.” Meanwhile, prominent members of Indian civil society, the great Indian historian Romila Thapar among them, challenged the arrest in the Supreme Court. This temporarily brought Bapu back home under house arrest.

The newly minted Unlawful Activities Prevention Act gives the Indian government the power to designate someone an enemy of the state without a trial.

I remember the morning of September 6, 2018—Bapu still under house arrest. We were all huddled in their living room around the TV, the adults on the diwan, and the children on the floor. We anxiously flipped from one channel to the next, between the regional Telugu news streams and the English-language NDTV. The Supreme Court was set to rule on whether Bapu would be taken back to prison. It was also the day that would become historic as the day homosexuality was decriminalized in India.

Hope came to me in a sudden burst of joy, brought by the unanimous decision of the Court that struck down Section 377, the provision against “unnatural sexual acts.” Suddenly, my country, my unforgiving, immoral country that could jail an eighty-year-old poet, turned softer, like ephemeral rain on scorched ground. People of all ages were celebrating on the screen, hugging each other and raising slogans, periodically stopping to wipe away tears. Inside the house, our celebration had an impatience to it. We all felt the precarity of that moment, wanting to believe in an India that embraced its people, and simultaneously fearing that, in mere minutes, we would discover that it did not embrace Bapu—not him, with his fiery poetry, not him who dreamt “of seizing syllables, from each of history’s furrows.”

Later that afternoon, Bapu passed around some of his new poetry, written recently while in jail. “These are incredible, perhaps we should thank Modi,” someone joked. Easy laughter came back to us, and even though his case’s judgment came soon after—an adjournment to a later date—I looked around and thought that this day mattered, one where a different world seemed possible.

As I struggled to read his handwritten words with their elegant curves, stumbling on my own mother tongue, I was struck by the loss of something I expected to possess forever. Like riding a bike, right? Telugu was my language. Did I inhabit a different world now? At the time, I was a graduate student studying public policy. I wondered what Bapu thought of me then, his Ivy League–educated niece, who could host entire book clubs dedicated to Audre Lorde and bell hooks but would be unable to muster the word for feminism in Telugu.

In India, wrote Mukul Kesavan, “English language pundits serve the same purpose as the Fool in Lear’s court: licensed tellers of occasionally uncomfortable truths.” This is not to suggest that English has no role to play in public debate, but in India, the real relationship between writers and movements thrives in vernacular readership and subaltern politics. This is historically true and also what I had observed in Bapu’s life’s work. Organizations he founded, such as Srujana, a Telugu journal that published radical literature for over a quarter century, and Virasam, a revolutionary writers’ association, both had a determinedly marginal audience, bucking the elite practices of literary culture. His work was built on the classic Marxist commitment, articulated by Jeremy Wong, of “faith in the intellectual, organizational, and political capacities of the working masses.”

Fascist governments, of course, know this only too well, and it explains their fear of a poet, especially one who operates in the vernacular. “One way of finding India’s public intellectuals,” Kesavan writes, “is to follow the bodies,” pointing toward the killings of Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare, who wrote in Marathi, and M.M. Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh, who wrote in Kannada. In fact, a 1974 conspiracy case lodged against Bapu by the state government attempted to demonstrate that all the actions of revolutionary movements during that period were a direct consequence of poems, speeches, and writings of radical writers. It ended in acquittal in 1989, after fifteen years of prolonged trial.

Yet Bapu’s self-critical words, unfailingly, come to me again from his 1990 poem “After All You Say”:

But for me—Used to reading man as a textCan the book become a substituteFor the world?

We had wanted to file a plea on the grounds of Bapu’s deteriorating health for some time now. He was the oldest amongst those arrested in 2018, had many serious health conditions, and was far enough away from home that Aamma, with her own ailing health, could not visit him often. He resisted: I am no more special than Saibaba or Shoma Sen, he said, insisting instead, even on those infrequent phone calls from prison, that we fight for so-and-so person or pass on information to so-and-so’s family.

In March of this year, it seemed like the humanitarian release of prisoners was gaining traction, especially as the Iranian government decided to release 85,000 people from its jails. What of those with “non-political” charges? It was a question I considered over and over. As Golnar Nikopur reminds us, “most of the ostensibly non-political charges for which people are detained in Iran, as elsewhere around the world,” (and certainly in India, I thought) “stem from self-evidently political issues linked to poverty and social difference.” Once I learned that Bapu was falling ill, however, worry turned these questions immaterial, into intellectual exercises that I could no longer afford.

By the time Bapu relented to filing an individual bail plea in April 2020, there were already thousands of confirmed COVID-19 cases in India and a few hundred deaths reported across the country. On April 15, his lawyer filed an interim bail plea. The National Intelligence Agency, which had, by then, taken over the case, swiftly opposed bail. Three days later, a Public Interest Litigation revealed deaths in three of Maharashtra’s jails, including Taloja, where Bapu was housed. The lawyer made a hurried phone call to the jail authorities; on the other end of the line, someone picked up but did not respond to their question. Friends, now anxious, began posting social media requests: “Can anybody contact Taloja jail? Or the Maharashtra government, or the media?”

“We have been extremely anxious,” wrote his three daughters, my cousins, in a widely published open letter released on May 27. They despaired that over the prior eight weeks, Bapu had been allowed to speak to his wife only three times, phone conversations no more than two minutes each. The court date arrived the next day. The jail authorities failed to furnish a medical report, and the hearing was delayed five days.

To many, campaigns for political prisoners conjure images of battles in courts, fought between heated lawyers waxing eloquent about ideology. In fact, they are very often about simply knowing someone’s whereabouts. Where is he? Could we see him?

The next day, a call from the local police station: He’s in the hospital. “Why? What happened? Is he okay?” We could not get more than a one-line briefing. That’s all they would offer. A news report claimed that he had been hospitalized not then, but three days prior. The official briefing differed: he lost consciousness just earlier, but his vitals were back to normal. We just wanted the truth. For many people, campaigns for political prisoners conjure images of battles in courts, fought between heated lawyers waxing eloquent about ideology. In fact, they are very often about simply knowing someone’s whereabouts. Where is he? Could we see him? About the days of COVID-19, Heidi Pitlor writes, “Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless.” What of time that feels like it’s running out?

When you have a loved one awaiting trial, the things that divide up your days become court dates—are we fully prepared, maybe there’ll be a judgment? The newly minted Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, or UAPA, gives the Indian government the power to designate someone an enemy of the state without a trial. This means that in India’s new unconstitutional regime, the effort to get a trial takes on its own unending rhythm. Before you realize, the nervous eagerness that precedes each hearing withers into slow defeat.

Again, the court date arrived on June 2. The judge was absent. A delay, three more days. The court date arrived yet again, the mysterious medical report was still missing. A delay, five days. The judge was absent. Two days. This time, the medical report appeared, but was yet to be read. A week. The prosecution needed time to prepare. Another week.

Hope. A trim, solid word. What does it feel like today? Purchasing a book for Bapu—he had asked to read Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). A text with a poem about him. His friends write one each day. A campaign, a new one, this time by Amnesty International.

June 26, and I’m staring at my phone again. The arguments have been heard. “ORDER RESERVED.” I began reading up on reserved orders: When might judges choose not to immediately deliver a decision? Is this a good thing? Is there additional evidence to review? Three hours in, DENIED.

In a 1990 poem, “The Other Day,” detailing the night before an arrest, Bapu asks:

In what discourseCan we converseWith the heartless?

On July 11, I watched as my aunt sat down in front of a camera for a press conference after receiving a call from Bapu that made clear his critical condition. Holding back tears, she urged, “I’m not asking for bail, for release, for anything—please get him medical care and save his life.”

In moments, I think I intend this to be a letter to him—perhaps some affection will get past the prison bars. Other times, I imagine it as a call to the public—maybe my anguish will agitate them. I am not certain anymore. Teju Cole once remarked: “Writing as writing. Writing as rioting. Writing as righting. On the best days, all three.” In this period of cruel waiting, perhaps mine is writing as remembering, and perhaps it will be a reckoning.