The Last Dinosaur

Nothing

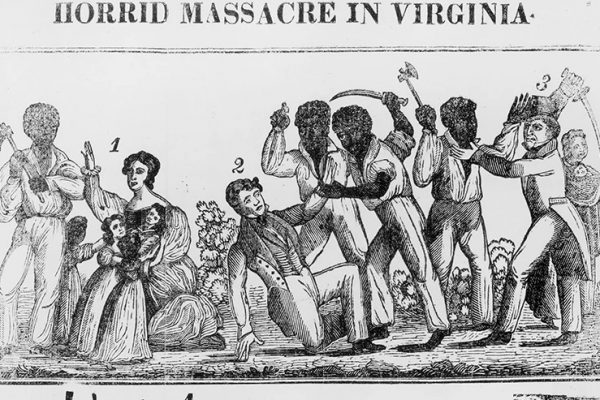

We are shoveling snow, this man and I, our backs coming closer along the drive. It’s so quiet I can hear every flake on my coat. I used to cry in a genre no one read. What a joke, they said, on fire. There’s no money in it, son, they shouted, smoke leaking from their mouths. But ghosts say funny things when they’re family. This man and I, we take the weight of what will vanish anyway and move it aside, making room. There is so much room in a person there should be more of us in here. I wave to you, traveler, inches away but never visible from where I am. Are you warm where you are? Are you you where you are? Something will come of this. In one of the rooms in the house the man and I share, a loaf of rye is rising out of itself, growing lighter as it takes up more of the world. In humans, we call this Aging. In bread, we call it Progress. We’re in our thirties now and I rolled the dough just an hour ago, pushing my glasses up my nose with my flour-dusted palm as I read, reread, the hand-scrawled recipe given me by the man’s grandmother, the one who, fleeing Stalin, bought a ticket from Vilnius to Dresden without thinking it would stop, it so happened, in Auschwitz (it was a town after all), where she and her brother were asked to get off by soldiers who whispered, keep moving, keep moving like sons leading their mothers through wheat fields in the night. How she passed through huddled coats, how some were herded down barb-wired lanes. The smoke from our mouths rising as the man and I bend and lift, in silence, the morning clear as one inside a snow globe. For how can we know, with a house full of bread, that it’s hunger, not people, that survives? The man pours a bag of salt over the pavement. But from where I’m standing it looks like light is spilling out of him, like the ray of dusty sun that found his grandmother’s hands as she got back on the train, her brother at her side, smoke from the engine blown across the faces outside blurring into pine forests, warped pastures, empty houses with full rooms. The man clutches his stomach as if shot, and the light floods out of him, I mean you—because something must come of this. Poetry makes nothing happen, someone who is dead now said after a friend’s death. When the guard asked your grandmother if she was Jewish, she shook her head, half-lying, then took from her bag a roll, baked the night before, tucked it in the guard’s chest pocket. She didn’t look back as the train carried her, newly seventeen, toward where I now stand, on a Sunday in Florence, Massachusetts, squinting at her faded words: sift flour, then beat eggs until “happy-yellow.” The train will reach Dresden days before the sky is filled with firebombers. More smoke. A bullet in her brother under rubble, his name everywhere outside her like the snow falling on your face forty years later, on December 2, 1984, while your mother carries you, alive only three hours, the few steps to the mini-van where your grandmother, nearly sixty now, crowns your head with her brother’s name. Peter! she says, Peter! Peter! as if the dead could be called back from rubble into new, stunned bones. The snow has started up again, whitening the path as though nothing happened. Oh, to live like a bullet, to touch people with such purpose. To be born going one way, toward everything alive. To walk into the world you never asked for but then choose the room where your hunger ends—which part of war do we owe such knowledge? It’s warm in this house where we will die, you and I. Let the stanza be one room, then. Let it be big enough for everyone, even the ghosts rising now from this bread we tear open to see what we’ve made of each other. I know, we’ve been growing further apart, unhappy but half full. That clearing snow and baking bread will not save us. I know, too, as I reach across the table to brush the leftover ice from your beard, that it’s already water. It’s nothing you say, laughing for the first time in weeks. It’s really nothing. And I believe you. I shouldn’t, but I do.

Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate or become a member.