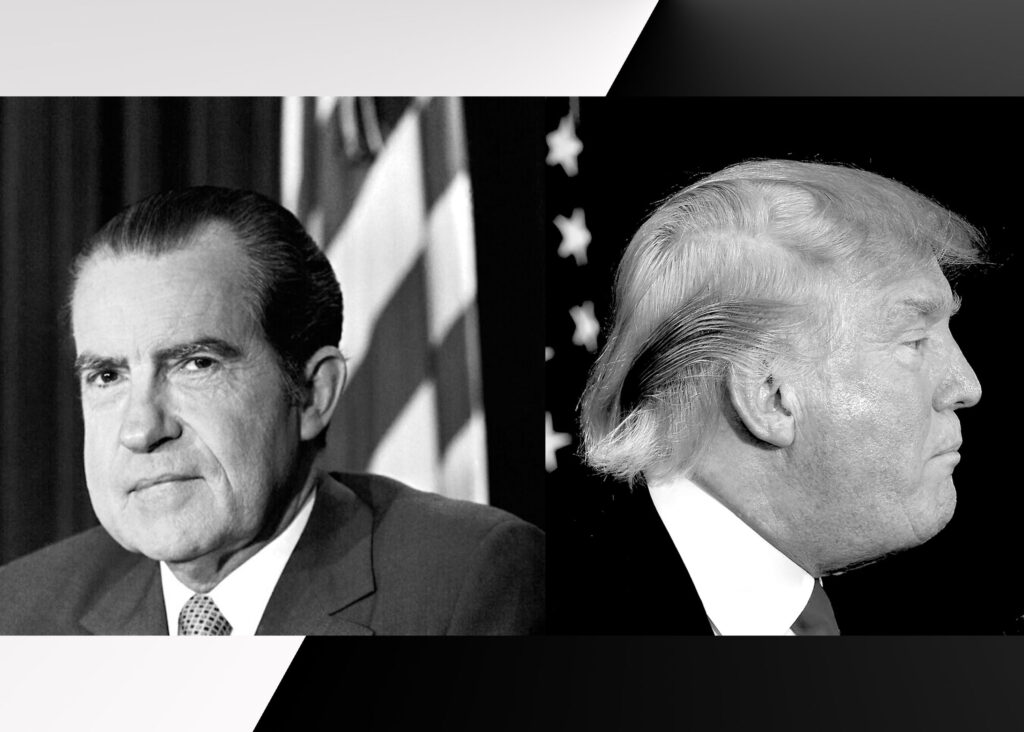

As the House January 6 committee lays out its case against Donald Trump for his part in an attempted coup, Americans may be drawn to reflect on the presidential scandal that began fifty years ago. In the early morning hours of June 17, 1972, police arrested five men at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C., triggering the Watergate saga. Over two years later, President Richard M. Nixon resigned, the only time in U.S. history that a president was forced out of office under the threat of impeachment. Following his resignation, his successor, President Gerald R. Ford, declared that the “Constitution works.” This has been the consensus view ever since.

However, a half-century of experience suggests that the Constitution does not work so well to check abuse of power in the presidency. Looking back at how Watergate progressed, it remains unclear how much we can attribute Nixon’s undoing to the Constitution working or how much owes to lucky breaks and the unique collection of personalities involved. Even if the rule of law ultimately prevailed in Watergate, it has become more difficult to contest presidential power since. Paradoxically, in the process of dealing with President Nixon, the institutions involved—Congress, the Supreme Court, and the special prosecutor—set precedents that made it harder to check a runaway presidency. Changes in the political dynamics in the intervening years have added to the difficulties. Americans may soon have a better understanding of how well the Constitution works today pending the outcome of the January 6 committee’s investigation of President Trump.

On June 22, 1972, a few days after the Watergate break-in, President Nixon met with H. R. Haldeman, his chief of staff. “It sounds like a comic opera,” Nixon said, so poorly executed that no one would think “we could have done it.” Haldeman agreed, picturing well-dressed men installing wiretaps with rubber gloves, “their hands up and shouting ‘Don’t shoot’ when the police come in.” Yet the arrests raised concerns at the White House. With less than five months before Election Day, Nixon and his advisers worried that the FBI investigation of the break-in might reveal other illegal activities.

They had cause for concern. Warrantless wiretapping and burglaries run out of the White House were not unprecedented for the Nixon administration. Indeed, some of those involved in the Watergate operation had previously broken into a Los Angeles psychiatrist’s office, seeking information to discredit a defense analyst who had leaked the Pentagon papers. The publication of this classified history led President Nixon to establish an off-the-books investigative unit known to White House insiders as the Plumbers because they would plug leaks. The administration also used “dirty tricks,” mostly juvenile tactics, such as stink bombs at rallies to disrupt the campaigns of Democratic presidential candidates. The most successful was a letter smearing the wife of Senator Edmund Muskie which sparked an emotional reaction from Muskie that knocked him out of the primaries. At the time, he was running even with Nixon. Then there were financial improprieties. International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation gave $400,000 to the Republican Party while engaged in negotiations with the Justice Department over an antitrust suit. Nixon decided to elevate supports for milk prices after dairy industry lobbyists agreed to contribute $2 million to his reelection campaign. Ambassadorships were for sale. Meanwhile, the president was using public funds for improvements on his own homes.

With all this at risk of discovery, the cover-up was “automatic,” said Jeb Stuart Magruder, a Nixon campaign official. “It seemed inconceivable that with our political power we could not erase this mistake,” he said of the break-in. Haldeman, John D. Ehrlichman, and John N. Mitchell (Nixon’s former attorney general who was heading up the president’s reelection campaign) directed subordinates to “deep six” incriminating evidence, which meant tossing it into the Potomac River. “Make sure our files are clean,” they instructed, and have “a little fire at your house.”

Nixon may not have known about the plans for the Watergate break-in, but he was deeply involved in the cover-up. On June 23, in a conversation with Haldeman, he approved measures to thwart the FBI investigation. This taped conversation, known as the smoking gun evidence of obstruction of justice, was crucial to Watergate’s outcome. Have the CIA “call the FBI in,” Nixon told his chief of staff, “and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case, period!” Later, when informed that the Watergate burglars had been “taken care of,” the president made his views clear: “They have to be paid,” he said, “that’s all there is to that.” And when the grand jury indicted the burglars, Nixon asked Haldeman, “Is the line pretty well set now on, when asked about Watergate, as to what everybody says and does, to stonewall?” The president also instructed his aides: “I want you all to stonewall it, let them plead the Fifth Amendment, cover-up, or anything else.”

As Nixon had hoped, Watergate wasn’t an issue during the ’72 campaign. He won forty-nine states and nearly 61 percent of the popular vote, close to the record. The rest of the story is hard to fathom today. Much of what transpired behind closed doors was found out; congressional hearings produced eyewitness testimony implicating Nixon in the cover-up; a grand jury named the president an unindicted co-conspirator; the House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment; the Supreme Court ordered President Nixon to relinquish sixty-four tape recordings of his conversations with aides; the most powerful members of Nixon’s inner circle were sentenced to prison; and a president who was willing to do anything to ensure reelection was compelled to resign in disgrace less than two years after a landslide victory.

To the extent that the system of checks and balances worked against Nixon, it did so slowly. Nixon and his men had engaged in sordid activities long before the break-in, and it was a tough slog for another two years before impeachment was imminent. As late as one month before the resignation, it was not clear that the House of Representatives would even impeach the president.

Judge John J. Sirica, presiding over the trial of the Watergate burglars, played a critical role early on. Nothing came out of the trial itself, thanks to hush money funneled through the White House to the defendants. Before the sentencing hearing, Judge Sirica announced that he was “not satisfied” that “all the pertinent facts” had been brought to light. Leveraging his power over sentencing, he told the defendants that their punishment would depend on their willingness to cooperate. A few days before sentencing, one of the defendants, James W. McCord, Jr., wrote a letter to Sirica which described “political pressure” to “remain silent.” He said that witnesses had lied and that not all of those involved had been identified. Sirica read McCord’s letter to those present in court and reporters immediately rushed out with the news.

Congress can be the 800-pound gorilla in the scheme of checks and balances. While bipartisan consensus was not assured from the start, there wasn’t the undeviating party-line opposition that would be expected today. Republicans who backed Nixon joined Democrats in authorizing the use of broad investigative powers. Some votes were overwhelming. Every senator voted to establish a select committee with subpoena power to investigate the campaign (the Senate Watergate committee). By a lopsided vote of 410-4, the House of Representatives authorized its Judiciary Committee to subpoena anyone to testify, including the president. Some GOP legislators even moved the investigation along. Republican Senators Charles H. Percy and Charles McC. Mathias Jr. led the drive for a special prosecutor, and when Nixon refused to comply with the Senate Watergate committee’s subpoenas, it was Republican Senator Howard H. Baker Jr. who suggested suing him. Although all Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee opposed authorizing an impeachment inquiry, seven later voted for at least one charge against Nixon. When unequivocal evidence revealed the president’s obstruction of justice, all the committee’s Republicans endorsed impeachment. President Nixon decided to resign only after several leading Republicans, led by Senator Barry Goldwater, informed him that he faced certain conviction.

What stands out among Congress’s actions is the Senate Watergate committee hearings, highlighted by John Dean’s testimony. Dean read from a 245-page single-spaced statement describing what he knew of President Nixon’s participation in the cover-up, stating that he had warned Nixon that Watergate was “a cancer growing on the Presidency.” One of their most memorable exchanges concerned the burglars’ demands for hush money. When Nixon asked how much they wanted, Dean suggested $1 million, which he thought was out of reach. According to Dean, Nixon replied that the amount “was no problem.”

Dean’s account put Nixon in jeopardy, but the president still had a chance to weather the storm. His defenders questioned Dean’s credibility, and many Americans were hesitant to take his word over the president’s. With the question of credibility hovering over the hearings, the committee called Alexander Butterfield, Haldeman’s former assistant, to testify. Butterfield admitted that the White House had tape recordings of Nixon’s conversations (committee staff had previously learned about them in closed-door sessions). This meant that Dean’s testimony could be corroborated by simply listening to the tapes. As it turned out, this was not such a simple task.

At this point in the investigation, the special prosecutor came to the fore. President Nixon probably would have survived the scandal if not for the tapes, which he might not have been compelled to turn over if there had not been a special prosecutor. In May 1973 Attorney General-designate Elliot L. Richardson appointed Harvard law professor Archibald Cox as special prosecutor. After Butterfield’s testimony, Cox sought the tape recordings of nine conversations. When Nixon refused his request, Cox persuaded Judge Sirica to issue a subpoena to the president. Nixon asserted that “the President was not subject to compulsory process from the courts,” and refused to comply, with his lawyers citing executive privilege. However, Cox argued that any presidential privilege that might otherwise exist was forfeit when “deliberations may have involved criminal misconduct.” Recognizing a qualified interest in presidential privacy, Judge Sirica ordered the tapes delivered to him for examination in chambers. Nixon appealed, but the appeals court upheld Sirica’s order.

With the court deadline to produce the tapes looming, Nixon offered to prepare a summary of the recordings to be authenticated by Senator John C. Stennis, even though the seventy-two-year-old Democratic senator did not have the capacity to undertake the task as he was recovering from a gunshot wound. Still, Nixon calculated that his proposal would put Cox in a bind, and he was right; Cox did not summarily reject the offer. He submitted counterproposals, but the White House would have none of that, and Nixon’s lawyer told him that he could not request any more tapes. On a Saturday afternoon in late October, the crewcut law professor appeared in a tweed suit before television cameras at the National Press Club and explained his position to the country. Meanwhile, he had decided to ask Judge Sirica to cite Nixon for contempt of court.

Cox never got the chance; Nixon ordered Richardson to fire him. The attorney general and his deputy, William D. Ruckelshaus, both resigned. The White House got the solicitor general to dismiss Cox, and Nixon’s press secretary announced that “the office of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force has been abolished as of approximately 8 P.M. tonight.” On orders from the White House, FBI agents sealed the special prosecutor’s office like a crime scene. There was, thought one reporter, “a whiff of the Gestapo in the chill October air.” Cox issued one last statement: “Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now for Congress and ultimately the American people” to decide—an unmistakable reference to impeachment.

The president’s actions backfired. Reactions to the Saturday Night Massacre, as it was called, were so intense that the president had no choice but to accept the appointment of a new special prosecutor: conservative Texas Democrat Leon Jaworski. He signed on with the understanding that he could not be fired without the consent of congressional leaders, but the public’s reaction to the Saturday Night Massacre insulated the new special prosecutor even more. Polling revealed a 12 percent increase in the number of people who thought Nixon should resign (from 31 to 43 percent) and who registered disapproval of his handling of the tapes (from 71 to 83 percent). Meanwhile, the House Judiciary Committee took up a preliminary inquiry into impeachment.

It is hard to overstate the public’s role in backing the institutional checks confronting President Nixon. As might be expected, members of Congress were particularly responsive to public opinion. Of the thirty-eight members on the House Judiciary Committee, fourteen developed their own questionnaires to measure constituents’ views on impeachment. Polls showed public support for impeachment jumping 13 percent one week after the House Judiciary Committee voted for the first article of impeachment. Lawmakers undoubtedly took notice. The press was also crucial in getting facts before the public. The story of the Washington Post duo Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward and their dogged pursuit of the facts has come to symbolize the essence of a free press in a democracy.

The battle for the tapes continued until the Supreme Court delivered the coup de grace in United States v. Nixon, ordering the president to produce the tape recordings subpoenaed by the special prosecutor. For all intents and purposes, the 8-0 decision ended the Nixon presidency. It was followed in short order by the release of the tapes (including the smoking gun tape), the House Judiciary Committee’s vote on impeachment, and Nixon’s resignation.

Congress subsequently passed a wide range of reform legislation. To insulate prosecutors from presidential interference, Congress enacted the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 which set up a novel process for appointing independent counsel. New election laws established the Federal Election Commission and limited campaign contributions and expenditures. The Tax Reform Act of 1976 had provisions responding to Nixon’s misuse of information collected by the IRS. Amendments to the Freedom of Information Act empowered judges to review classified materials, and the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 enhanced protections for government whistleblowers.

The irony of Watergate is that, in responding to Nixon’s abuse of power, the Supreme Court, the House Judiciary Committee, and the special prosecutor set several precedents that have since made it harder to check the abuse of presidential power.

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of executive privilege may qualify as the supreme irony. Before Watergate the constitutionality of executive privilege was an open question. Nixon was not the first president to block Congress and the courts from hearing testimony of executive officials or obtaining documents. President George Washington withheld documents lawmakers requested relating to a botched military expedition. In modern times, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stands out for refusing to allow subordinates to testify in the McCarthy hearings. Yet the Supreme Court had never recognized the constitutionality of executive privilege until United States v. Nixon. The uncertainty surrounding executive privilege prior to that decision is obvious in comments Nixon made to Haldeman. Focusing on public relations, as was his wont, he worried that “privilege” was a “very bad word,” because “it means we’ve got something they don’t have.”

United States v. Nixon was double-edged. Though it ended the Nixon presidency—he resigned sixteen days later—the Court also determined that the “confidentiality of presidential communications” has “constitutional underpinnings.” By constitutionalizing executive privilege, the justices enhanced the ability of future presidents to fend off investigations. Although the Court’s opinion qualified the scope of the privilege with its focus on national security, presidents have since taken a broader view. Even if a particular claim of executive privilege is unlikely to stand in court, merely asserting it can enable presidents to delay investigations.

The House Judiciary Committee also made it harder for the legislative branch to make full use of its power of impeachment by rejecting a proposed article of impeachment on the bombing of Cambodia. As a model for subsequent impeachment, this narrowed the scope of what qualifies as an impeachable offense. President Nixon had ordered a bombing campaign of Cambodia, a neutral country, during the Vietnam War. Nixon and his closest aides managed to keep over 3,600 bombing missions secret from Congress and the public while informing a handful of senators friendly to the administration. The deception was accomplished by falsifying records, maintaining a double ledger accounting of bombing raids, swearing servicemembers to secrecy, running operations out of the White House basement, and keeping the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the dark.

Presidential war-making—engaging the nation in military hostilities without congressional authorization or by deceiving Congress and the public—has been a problem since the Korean War. By the early 1970s, with opposition to the Vietnam War at a high point, the time was ripe for Congress to reassert itself. The War Powers Resolution adopted in 1973 was designed to rein in presidential powers, but it has been less effective than its supporters hoped. Impeachment might have been an additional deterrent, but that option became harder to use after the House Judiciary Committee’s decisive vote (26-12) against charging Nixon for the unauthorized bombing of Cambodia.

Another implicit precedent that can be drawn from the Watergate scandal is that presidents, no matter how deeply involved in criminal activity they may be, will not be prosecuted. Before Watergate it was generally understood that former presidents were subject to criminal prosecution while sitting presidents must first be impeached and removed from office. Yet with the failure to prosecute Nixon, who was clearly in legal jeopardy for obstruction of justice among other things, post-Watergate presidents seem to have something resembling immunity from prosecution. Jaworski was reluctant to prosecute Nixon after he resigned because he was concerned about assembling an impartial jury. The question became moot after President Gerald Ford pardoned his predecessor. Although the pardon implicitly conceded that Nixon could have been prosecuted, Nixon never publicly admitted guilt, and the concerns expressed by Ford and Jaworski would apply to any criminally liable president embroiled in scandal.

Another byproduct of Watergate concerns the burden of proof required to impeach the president. The Constitution does not state what evidentiary standard applies. The reasonable doubt standard used in criminal cases seems appropriate, but the June 23, 1972 smoking gun tape gave rise to a cultural expectation that, to impeach and convict the president, there must be definitive proof comparable to the tape recording of Nixon’s conversation with Haldeman.

Just because the case against Nixon was clinched with a smoking gun does not necessitate one in the future. Yet the public discussion surrounding subsequent presidential impeachments suggests that is the expectation. During President Bill Clinton’s impeachment, reports referred to physical evidence (Monica Lewinsky’s dress) as a smoking gun directly contradicting his statements. President Ronald Reagan defused the impeachment threat posed by the Iran-contra congressional hearings by saying “there ain’t no smoking gun.” During Trump’s first impeachment, news reports featured headlines such as “Do Democrats Have Enough ‘Smoking Gun’ Evidence for Impeachment?” (FiveThirtyEight). Discussion surrounding the second Trump impeachment compared the Senate Republicans’ resistance to convict against smoking gun evidence: “The Senate Got Smoking-Gun Evidence of Trump’s Guilt. 43 Republicans Didn’t Care” (Washington Post).

Whatever conclusion one draws about the Constitution’s success in Watergate, it is hard to imagine the various checks on the presidency working in the same way today. Watergate suggests that they work best in concert, but given the state of U.S. politics today, the odds are stacked against these institutions joining forces to counter a presidency gone off the rails.

In the years since Watergate, congressional committees have undertaken several high-profile investigations of executive behavior—some justified, others less so. Rarely do they approach the Senate Watergate committee’s accomplishments in rooting out the facts and communicating their constitutional significance to the public. Although Congress has certainly picked up the pace in impeaching presidents since Watergate, the outcome seems predetermined by party affiliation, in contrast with the Nixon impeachment inquiry when Republicans were swayed by the evidence. In the Trump impeachments, whether the Democratic impeachment managers could have convinced two-thirds of the Senators to convict is unlikely in any event, but recent events have clarified the seriousness of the charges. The first impeachment concerned whether President Trump had withheld military aid authorized by Congress from Ukraine in order to pressure that country’s leader to announce an investigation of Hunter Biden, Joe Biden’s son. The second, of course, concerned the attack on the Capitol. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s ruling on executive privilege in United States v. Nixon had an impact. Democratic lawmakers admitted that Trump’s claims of executive privilege hampered their investigations and limited the scope of the charges they brought against him in his first impeachment.

If today Congress seems hopelessly divided, the same might be said of the Supreme Court. In contrast to the unanimous decision in United States v. Nixon, a party-line split would not be surprising in cases as politically charged. This has been the pattern from Bush v. Gore (2000), the rushed 5-4 decision that ended the recount process in Florida, to Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021), which undermined the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The question of how to empower a prosecution team to conduct an independent investigation of presidential wrongdoing still lacks a satisfactory answer. The Watergate special prosecutor played a critical role in unraveling the cover-up. Yet the Saturday Night Massacre exposed the inherent difficulty with attorneys within the executive branch—even special prosecutors—maintaining independence from the president. Cox and Richardson were as committed as anyone to that goal, and that was still insufficient to withstand President Nixon’s power. Congress responded five years later with the Independent Counsel Act which authorized federal judges to appoint an independent counsel upon the attorney general’s request. Over time Republicans and Democrats alike grew disenchanted with this setup. Republicans were troubled by Lawrence Walsh’s investigation of the Iran-Contra affair. Kenneth Starr’s investigation of President Clinton drew Democrats’ ire. When the independent counsel legislation was due for renewal in 1999, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle let it lapse. The Justice Department came up with a middle-ground approach by establishing the position of special counsel.

This approach was put to the test during the Trump administration. As questions arose about Russian interference in the 2016 election, Robert S. Mueller III was named special counsel. He appeared to be the logical candidate for the job given his background as FBI director and U.S. attorney, with experience in public corruption investigations. Mueller put together an excellent team—few could have equaled the pace at which they worked and there was little doubt of their professionalism to independent observers.

Although Mueller’s team secured several convictions and produced a detailed report, his investigation pales in comparison to the Watergate special prosecution force. Operating under the Justice Department’s special counsel regulations, Mueller did not have the autonomy that the independent counsel had. He had to report to Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein, who had the final say over the investigation’s scope. Rosenstein, whom Trump could have fired, directed Mueller to refrain from investigating Trump’s business interests with Russia, despite legitimate national security concerns over Russia’s leverage over the president. Trump’s unceasing threats against the special counsel had impact, not so much because Mueller and his lawyers were intimidated, but rather because the sniping may have led Mueller to complete the investigation before Trump could have him fired. Significantly, he never interviewed the president. Moreover, the way Mueller communicated his prosecution team’s findings to the public left much to be desired, as he seemed to believe that detailed investigative work and legal professionalism would speak for itself. But this is not how events play out in the legal and political world of presidential scandals.

The report’s confusing presentation of Trump’s culpability for obstruction of justice illustrates how hard it is to contemplate prosecuting a president after Watergate. Mueller felt bound by a Justice Department opinion issued during the Watergate scandal that concluded that a sitting president cannot be indicted. Since Mueller believed he could not bring charges against Trump while he remained in office, he said he could not “draw ultimate conclusions about the President’s conduct.” This led him to make a convoluted statement that “we are unable to reach” the judgment that Trump “clearly did not commit obstruction of justice.” This was all Trump needed to claim that the special counsel had exonerated him. “NO OBSTRUCTION!” was his Twitter response. Mueller’s difficulty in public communication was compounded by the fact that he could not release his final report until the DOJ approved. Attorney General William P. Barr took advantage of the delay to issue a misleading summary.

As the people represent the ultimate check on presidents, changes in the character of the body politic are especially disconcerting. Despite the polarized politics of the Watergate era, in the end there was a widely shared sense of constitutional limits (which Nixon had crossed) and a view that his efforts to manipulate the electoral process were antithetical to U.S. democratic norms. Today’s public, by contrast, is deeply divided on the fundamentals of constitutional democracy. In today’s fractured media landscape, it is unlikely that such a divided public would coalesce in opposition to a president as it did against Nixon, when his 59 percent job approval rating in April 1973 fell to only 13 percent who believed, following his resignation, that he should have remained in office.

Since Watergate, Americans have expected the equivalent of Nixon’s smoking gun tape as evidence to justify presidential impeachment. Surely no less would be expected for prosecuting a president. Now, with President Trump, who once said that he “could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and . . . wouldn’t lose any voters,” the question has shifted. The January 6 committee may very well offer smoking gun evidence implicating the former president in nothing less than a seditious conspiracy, the question is whether even that will fail to lead to his prosecution.