LYNDA HULL (1954–1994)

Lynda Hull, like Walt Whitman, not to mention Dorothy Parker, William Carlos Williams, Allen Ginsberg, W. S. Merwin, Anne Waldman, Patti Smith, & Amiri Baraka, was born on the mystifying planet of New Jersey. Hull’s poems dazzle like the lighter fluid inside the sturdy, stainless steel lighter she stole from her father, a spout of spitfire, when she ran away from home at sixteen. “I remember this the way I’d remember a knife against my throat: that night, after the overdose, you told me to count, to calm myself,” Hull writes in “Counting in Chinese,” a poem derived, one assumes, from Hull’s years high as the moon on the lam in Chinatown, married to an outlaw gambler from Shanghai. Taking up her pen & mostly laying down her syringe, Hull was divorced & remarried to a poet by 1984, living on fugitive wonder & figurative language, lines of Hopkins & Akhmatova in Arkansas &, later, Indiana. Hull sometimes read her poems wearing dangling earrings & ankle-strapped high heels with her flapper’s hairdo dyed the same color as her beret. In addition to lighter fluid, Hull’s poems display the properties of rain just before it evaporates. Hull’s poems hold saltwater: “Tide of Voices” in Ghost Money (1986), “Shore Leave” in Star Ledger (1991); “Rivers into Seas” in The Only World (1995), published a year after her death in a car crash in Provincetown a few miles from the beach. When she wakes on the other side, Hull spends the hours she’s not writing poetry mulling figures of wonder with holy wine while listening to fugitive jazz. Sometimes Bird appears with his horn on the cover of Ornithology. Having retained her uncanny ability to channel varieties of sound, Hull scats to Bird like Ella Fitzgerald wiping sweat from her brow. Sometimes ghosts come by. When she was alive, Hull memorized the entirety of “The Bridge,” a fifty-six-page multi-section poem about the Brooklyn Bridge written by Hart Crane, Hull’s favorite poet, in 1923 when he was twenty-three & working as a copywriter in Cleveland, nine years before his suicide. Hart Crane comes by sometimes. Hull regales him with passages of “The Bridge” long into the eternal evening.

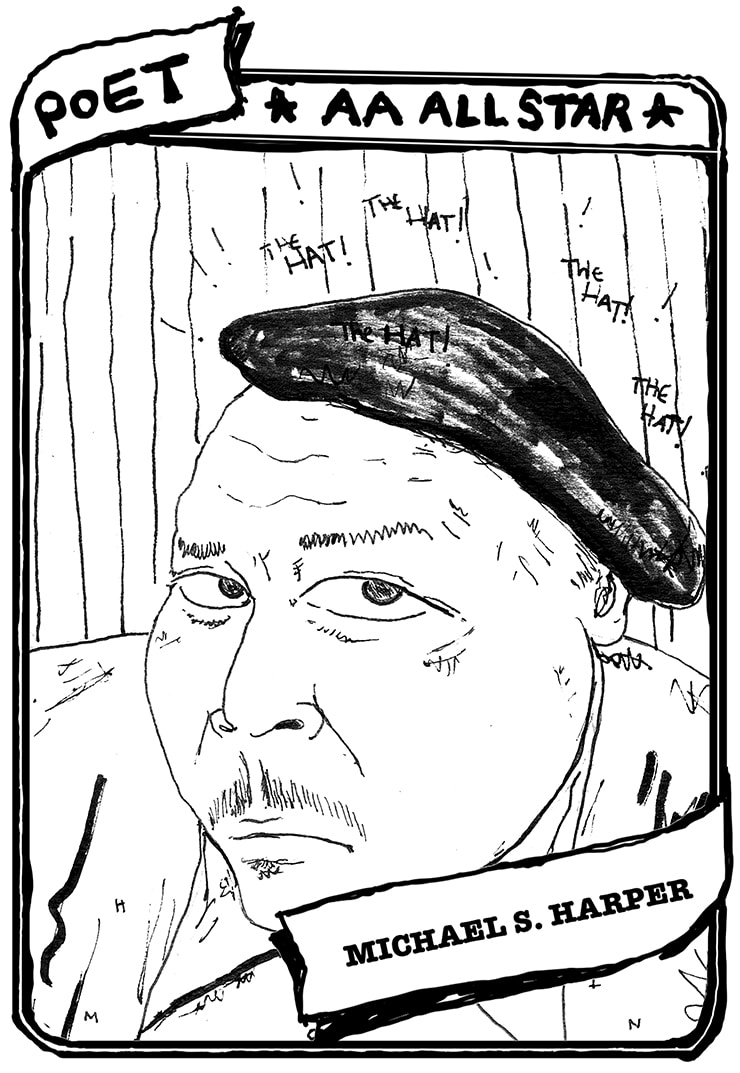

MICHAEL S. HARPER (1938–2016)

Beneath the hat is a brain born in Brooklyn in 1938. Beneath the hat is “My Father’s Face,” “My Mother’s Bible.” Beneath the hat is Robert Hayden, the Negro Folk Tradition, Providence, the speckled blues-poet-professor-mentor Sterling Brown & the mad-sanctifying-farmer-turned-abolitionist John Brown. Beneath the hat is “The Militance of a Photograph in the Passbook of a Bantu under Detention” which opens with “Peace is the active presence of Justice” & details a Black man with pus swaddling his bandages. Beneath the hat is the shape of an oak’s trunk laid bare by the homicidal chainsaw of the State. Beneath the hat is Coltrane asleep on a train dreaming the names of trees between New York & Philly. Beneath the hat is “MSH.” Beneath the hat is all of “History as Apple Tree,” “History as Polka Dots & Moonbeams,” “History as Diabolical Materialism.” Beneath the hat is the ghost of the brother who died in a motorcycle accident. Harper had two children who died at birth. “Song: I Want a Witness.” Beneath the hat is a church of four Black girls blown up in Alabama, a net of five hundred Middle Passage Blacks under water in Charleston harbor. Cries & songlines spill from a tenor tethered to the gut of a Black man playing on a warped record playing on a warped record player beneath the hat. Beneath the hat is “American History,” “Bigger’s Blues,” “Elvin’s Blues,” “Martin’s Blues,” a Black man’s view of suffering, a Black man’s view of beauty, a Black man’s view of faith. Beneath the hat is a place a Black man can place a few small apples for his children. Beneath the hat is the oily salty smell clinging to the skin of the apples when the children eat them.