Horizons Circled: Reflections on my Music

Ernst Krenek, with contributions by Will Ogdon and John L. Stewart

University of California Press, $8.50

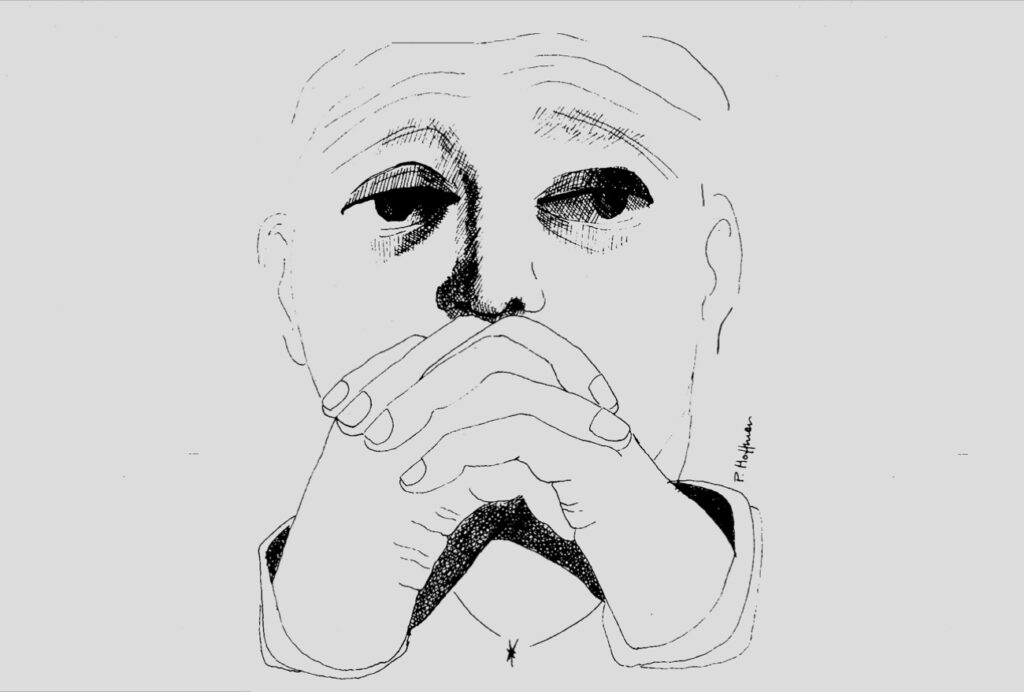

At Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music in the summer of ‘53, the big news was the appearance of Ernst Krenek. And the first reports I heard about the appearance of Krenek had to do with Krenek’s appearance.

“Would you believe it,” a conferee confided, “no socks!”

“Come again?”

“No socks. The guy crossed University Ave. with no socks, and in a pair of sandals, too.”

Krenek is, to cite one of Igor Stravinsky’s insufferably patronizing pronouncements, ‘an intellectual and a composer—a difficult combination to manage.’

“Incredible” I conceded, mobilizing my backup scarf as a Linus-blanket, “but L.A.’s a breeding-ground for eccentrics, you know.”

Later reports, and first-hand observation, confirmed that Krenek also wore his learning lightly. In town, on that occasion, to conduct a master-class, he impressed as a brilliant analyst who nonetheless reckoned with the perils of cerebral exclusivity. I remember once confronting him with the score of Schonberg’s Piano Concerto for which I’d prepared a tone-row errata—a list of deviations from the operative series. “Could any of these be other than a slip of the pen,” I asked; “I mean, could any of them possibly be—blush—stammer (this was ‘53, after all, and most of us were hard-edged constructivists) the result of—gulp—inspiration?” “I wouldn’t want to second-guess Schonberg,” Krenek replied, “but I don’t see why not.”

Krenek, in short, was, and is, a scholar and a gentleman or, to cite one of Igor Stravinsky’s insufferably patronizing pronouncements (as orchestrated by Robert Craft), “an intellectual and a composer—a difficult combination to manage.” “He is also,” Stravinsky informed his Boswell, “profoundly religious which goes nicely with the composer side, less easily with the other thing.” (What a pity Bob and Igor didn’t try hanging that on Etienne Gilson.)

Krenek is, indeed, one of the least understood of contemporary musical figures. The most prolific major composer of our time—the late Darius Milhaud, depending upon how much major-ness you accord him, would be his only serious rival in the numbers game—Krenek is perhaps best known to the public at large as “Ernst who?” Of his output to date—two-hundred and twenty-five works and counting—less than half-a-dozen (none of them major items) are represented in the current Schwann catalogue. He fares better in Europe; some of his twenty-odd operas (the cornerstone of his output) are mounted with reasonable frequency, and most of his commissions originate on the continent. But Krenek remains an enigma to many because that vast output is not idiomatically concentrated in the manner of, say, Hindemith or Britten or Shostakovich—half-a-dozen works from any of those gentlemen provide a reasonable overview of their aesthetic. Krenek’s work, on the other hand, employs a bewildering collection of idioms and a formidable arsenal of techniques. In the 20’s, he tilted toward Bauhaus-baroque, then flirted with jazz and an overlay of social comment; in the 30’s, he converted to Schonberg’s twelve-tone technique and, in the 40’s, modified it by a rotational system of his own—somewhat akin to the leapfrog row technique of Alban Berg. In the 50’s he employed a multiparametered serialism, in the 60’s puttered about with tape technology, and, in recent years, has come to grips with the post-serial dilemma of choice vs. chance.

His work tends towards the lyric, the elegiac, the euphonic—qualities which mirror a singularly generous, contemplative, unaggressive personality.

Casually enumerated, it reads like the dabbling of a dilettante, like the overanxious, “me-too” ism of the born eclectic. But it isn’t. For though Krenek does have an insatiable musical curiosity and is quite capable of an “I’ll try anything once” response to external stimuli, he is quite incapable of the argumentative, Stockhausenesque carbon-dating which subs for analytic comment in the columns of so many European music journals. (“Sir: In response to your article ‘Structural Principles of Inaudibility’, I should like to point out that I, and not my colleague Hans-Heinz Hopflinger, must take credit for the introduction of isorythmically-organized fermatae. I draw your attention to the tacit tympani in my ‘Permutations IV’ which anticipates, by no less than 17 days, Hopflinger’s ‘Assymetry XVI’, and which was completed August 21, 1955. If further verification is required, I refer you to my former copyist, Felix Daub, who can be contacted c/o Zauberberg Sanatorium, Zurich.”)

All of Krenek’s mature work, indeed, no matter the idiom, is of a piece—held together by a unique musical temperament. His work tends towards the lyric, the elegiac, the euphonic—qualities which mirror a singularly generous, contemplative, unaggressive personality. He is, in fact, the antithesis of the artist as egotist—which may well be the basis for his P.R. problem. It could also explain his correct but rather strained relations with the late Arnold Schonberg—the very model of a modern major genius. “One always felt that he was testing you,” Krenek related recently, “waiting for you to make a mistake: and then he would start a fight, hoping to destroy you.”

One does not, needless to say, produce two-hundred and twenty-five works while catering a crisis of confidence, and Krenek is not unaware of the value of his contribution and by no means disinterested in its effect upon posterity. Indeed, in a cryptic, and rather uncharacteristic, comment in his 1951 essay “On Writing My Memoirs” he disclosed that arrangements had already been concluded with the Library of Congress for the deposit of private autobiographical papers which will go public fifteen years after his demise.

“Why should I expect anybody to trudge to Washington fifteen years after my departure from this world in order to find out what I thought I had been doing while still alive? … The main reason for my writing this huge autobiographical book [is] my conviction that some day my musical work will be considered far more significant than it is at this time and that then people will try to discover what made me tick.”

There is, however, a pervasive repose at the core of his being, and its musical corollary—a certain lack of tension and absence of agitation—is responsible for the deceptively bland impression which his works sometimes leave with the uninitiated. On the other hand, it is precisely this quality which makes his Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah one of the great musical-religious experiences of our time and his Symphonic Elegy (on the death of Webern) perhaps the most moving tribute ever paid by one musician to another. I also suspect that this sense of perspective, of detachment, which characterizes so much of Krenek’s music, however superficially au courant it may appear to be, is not simply the product of a facile technique (though certainly the poignant note-by-note agonies of an Alban Berg are unknown to Krenek), nor even of the dialectical compromise between Marxist activism and Christian forbearance which merge in his character to form an almost Shavian exuberance, but relates rather to the fact that Krenek is one of the very few composers with a sense of history.

By and large, composers shy away from history much as pop-stars avoid learning to read scores. Krenek is one of the very few composers with a sense of history.

By and large, composers shy away from history much as pop-stars avoid learning to read scores. Both breeds are spooked by book learning and frequently prefer to treat inspiration as a subterranean flow without geological consequence. For Krenek, however, history is not simply an ordinance depot for a personal crusade (though his extensive research into the fifteenth-century Flemish master, Johannes Ockeghem, certainly provided ammunition for his theories of twelve-tone evolution) but rather, I would guess, a means by which his own contribution can be seen in relation to a larger good. Still, he is a composer and, from time to time, Hamlet-like, gives that old devil ambivalence its due.

In the first of the four lecture-reprints which form the centerpiece of Horizons Circled, Krenek states:

I have criticized because I apparently found it necessary to search for historical prototypes in order to justify modern compositional methods. I feel that such objections are based on a misunderstanding. The fact that the melismata of Gregorian chant displayed inversion and retrogression, or the fact that some medieval composers like Dufay used the cantus firmi as basic melodic patterns from which they derived individual motivic shapes for their polyphonic designs, did not in my opinion justify application of such procedures in the twelve-tone technique…

What I was interested in was observing and experiencing the permancy of certain ways of musical thinking. I was also interested in the existence of archetypes that seemed to run through the known history of occidental music and, from time to time, to crystallize in the shape of stylistic entities …. Today I am no longer so convinced that this historical orientation is as necessary or useful as I thought under the impact of my own historical study …. If we feel that history takes its course ac cording to some inexorable internal necessity, it would not seem to make very much difference whether or not we are aware of its preordained pattern. If we feel that we are making history as free agents, we may not pay much attention to precedent, only to be told afterward that our actions were a logical consequence of all that went before. “To be or not to be historically oriented” is a question that cannot be answered any better than the question “To be or not to be,” period—or rather, question mark.

The lectures were originally delivered in 1970 when Krenek was appointed Regents Lecturer at the University of California, San Diego, and, throughout the set, the author deftly mates general observation with personal experience. The historical reflections in the first paper encourage him to ponder his own stylistic development; in the second, which explores the political ramifications of art, Krenek supers a description of his operatic masterpiece, Karl V, the work which put him on the Nazi blacklist, upon a backdrop devoted to Anschluss stratagems in his native Austria.

The third lecture is an analysis of the socio-economic dynamics of art, and the fourth a dissertation on serialism in general and Krenek’s Sesrina for soprano and ten instruments in particular. This work (even for those of us who remain skeptical about the “logic” of serialism) is a triumph of communication over process, and, for the musician, Krenek’s schematic diagrams are invaluable. Nevertheless, despite Krenek’s gently waspish comments about aleatory group-improvisation, and mixed-media (“I share the attitude of the Shah of Persia who, when invited by the Austrian emperor to watch the horse races, replied, ‘thank you very kindly, your Majesty, but I know that some horses run faster than others, and which ones, I don’t care’”), this latter piece will be rather heavy going for the lay reader as, indeed, will Will Ogdon’s “Horizon Circled Observed” a detailed analysis of the orchestral work which lends its name to the present volume.

On the other hand, the minutes of a conversation in which Ogdon plays Jonathan Cott to Krenek’s Stockhausen (I avoid the more obvious Craft-Stravinsky analogy because Krenek has never been in need of a ghostwriter) neatly sums up the composer’s attitude toward the contemporary scene. The remaining items in what is, essentially, a Festschrift geared to Krenek’s 75th birthday are an appendix chronologizing his complete musical and literary output and a brilliant essay by John Stewart on Krenek, the litterateur. This latter piece is of particular value because Krenek is, to put it mildly, a nifty stylist, and an analysis of his verbal skills is long overdue.

Krenek has served as his own librettist for sixteen of his operas—though Kafka, St. Paul, and (I’m not making this up) the Sante Fe Railroad timetable have all been put to music.

Krenek has served as his own librettist for sixteen of his operas, his own lyricist for innumerable songs and choral pieces—though Rilke, Kafka, John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins, St. Paul, and (I’m not making this up) the Sante Fe Railroad timetable have all been given a piece of the action at various times. Through the years, first in German, more recently without benefit of translation, he has contributed meticulously crafted essays on subjects ranging from Johann Strauss to the collected works of Franz Kafka—not to mention his specifically musicological studies.

Last year, in an article for the Toronto Globe and Mail, I compared Krenek to George Santayana—strictly on stylistic grounds; similarities of character and outlook would be hard to come by. I speculated that the superb sense of cadential rhythm which both authors possessed might relate to the fact that, not having been born to the language, both were therefore free to super its data upon central-European rhythmic conceits. As a musician, I was, of course, primarily preoccupied with matters metrical, but Stewart, as a Professor of Literature, is more concerned with thematic analogy and claims that:

[L]ike many contemporary writers he is concerned with man as a member of a group … with the identity of the individual in terms of traditions that make possible selfhood in communion, with the meaning of a moment of personal experience in the history of a culture much threatened by disorder. His kinship, therefore, is more with writers like Yeats, Eliot, Mann, and Faulkner. Or, in his attention to the absurd, with writers like John Barth and Beckett.

But the one he most resembles is Joyce, unlike as they are in temperament. Both are acute observers of the human scene with a relish for the ridiculous. Both have a strong sense of historical parallels and use the legends of Greece and their native lands to interpret the present. Both are versed in Catholic doctrine and know well the paradox of man’s need for support from such ancient dogmas, coupled with his need to assert and maintain his individuality before them. Both have used that paradox in exploring problems of freedom, order, “progress” in the arts, the artist as seer, the relation of the arts to action. Though seeking to speak through their works on some of the great issues of their age, both have been driven by the momentum of their creativity, and by their refusal to compromise, into using idioms that have alienated them from those they with to reach. Both have enjoyed the admiration of their fellow-artists who, more readily than most, have seen what they were about and could appreciate the effort, integrity and achievement.

Finally, apropos nothing in particular, a fan’s note: on Easter Sunday 1964, at Orchestra Hall, Chicago, I played my last public concert. It was an event to which I’d looked forward for a decade, and, by way of celebration, I decided to spend three days in training, need it or not, and to choose works which, through the years, had held a special meaning for me. The program drew upon Bach’s Art of Fugue, Beethoven’s Op. 110, and the Third Sonata by Ernst Krenek.

Originally published in the Winter 1975 issue of Boston Review