Two scenes from twenty-first-century America.

Young friends cycle to church for Sunday services. They stash their bicycles by the side of the building, walk in sporting their aerodynamic spandex, and take their places in the pews. Later that day a waitress at a nearby restaurant approaches a silver-haired couple squinting at their menus. “So, what can I get you guys?” she asks the pair.

Across a range of behaviors, from dress to forms of address, Americans have become strikingly informal: we deviate from convention more than we used to, and the conventions we do observe entail less deference to institutions such as churches and statuses such as advanced age.

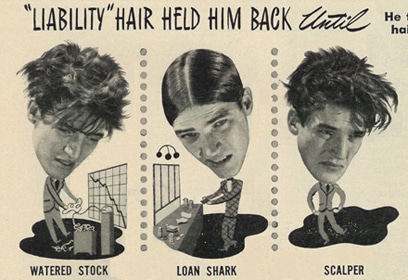

Scholars have traced the evolution of manners as described in etiquette manuals. For much of modern history, standard-setters pressed their aristocratic readers to discipline themselves: to control body functions such as passing wind and suppress emotional outbursts such as uproarious laughter, to stand with good posture and speak with proper deference and decorum. As a schoolboy, George Washington dutifully copied down such advice as, “If you have reason to be [angry] . . . Shew it not but [put] on a Chearfull Countenance.” In the nineteenth century, Americans in the growing middle class relied on advice books and magazine articles to guide their entrance into proper society. They also imposed such standards on working-class and immigrant youth at school, in church, and on the factory floor. Manners became more formalized for more Americans. No to hacking tobacco-stained phlegm onto the floor, yes to presenting calling cards at the door.

During the twentieth century, standards shifted toward informality. Popular behavior pressed against the old norms—women bicycled in bloomers and danced the Charleston—and some manners experts blessed the shift. The popular etiquette writer Emily Post started her career dictating strict rules of behavior, but letters from readers led her to loosen up considerably. In 1922 she wrote, “About twenty years ago the era of informality set in and has been gaining ground ever since.” Etiquette experts often prided themselves on endorsing greater simplicity and spontaneity—even women smoking.

Fashion reveals the changes. In photographs of World Series crowds from a century ago, men and boys almost uniformly wear jackets, ties, and bowler hats. Sometime after the 1960s, the dress code became hooded sweatshirts, T-shirts, or parkas. In 1961 Bruce Gimbel, head of the now defunct department store Gimbel’s, complained about the casual clothing trend. Merchandisers were “not making enough effort to create the image of the well-groomed boy who goes to school in a suit with shirt and tie,” he said. If the shirt-and-blue-jeans trend were not checked, he warned, “Future generations of fathers may well be dressing in exactly this fashion when they go to their jobs as executives and white-collar workers.” (He was right—think of Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, and Tim Cook.)

Controversies over increasingly informal dress vex contemporary churches. Two years ago in Christianity Today, an older writer complained, “In many churches casual wear is de rigueur. . . . Relaxed, even rumpled informality is in; suiting up in our ‘Sunday best’ is out.” A Presbyterian minister in Virginia takes the other side: “Ties are not more holy than T-shirts. . . . Dress shoes are not more holy than bare feet.” Informality is just as acceptable as fine attire, “as long as we’ve done it to His glory and in love for others.” The United Church of God disagrees: “We expect the men in the congregation to wear a shirt, tie and quality slacks. . . [the ladies] to wear the best dress, suit or pantsuit you can afford.”

Although less well-documented than clothing, interpersonal manners have also moved toward informality. Sociologist Cas Wouters found that the etiquette mavens of the twentieth century relaxed constraints on individual behavior, with but one exception: “displays of superiority and inferiority” became more taboo. Using first names in introductions, once a no-no, became so common by the 1960s that, as one advice writer conceded, “Some people do not care for this extreme informality, but, by today’s standards, it is stuffy to make a point of the matter.” First names for customers, teachers, strangers on the telephone, and name tags at conferences exemplify the trend.

American families have also increasingly chosen to portray themselves informally. Family photographs in homes are rarely stiff portraitures anymore; instead they depict casual scenes and casual postures as well as casual clothes. And Americans have downplayed obedience, good manners, and conformity as values worth teaching their children, preferring instead to instill independent thinking, responsibility, and considerateness. How many children address father as “Father,” much less as “Sir,” as proper children did more than a century ago?

Foreign visitors have long been struck by average Americans’ informality—our penchant for addressing people to whom we have not been introduced, ignoring social distinctions, being a bit slovenly and generally bumptious. These habits seem to reflect our egalitarianism, which was quite radical for the early nineteenth century. Much greater informalization since then may have resulted from yet further social leveling—between propertied and not, young and old, men and women, white and black, even parent and child.

A new cultural tide, carrying yet more informalization, arrived with the baby boomers in the 1960s and ’70s. An ethos that had been at the core of American individualism for centuries attained greater force. Under the many layers of social mores rests a unique self that must find “authentic” expression, which requires discarding the falsity, superficiality, and conventionality of custom—be it in clothes, makeup, or speech.

Among the several versions of this story, the late sociologist Ralph Turner, writing almost forty years ago, distinguished between defining oneself in terms of the social roles one inhabits—as wife, mother, daughter, doctor, neighbor—and defining oneself in terms of personality traits—as cautious, loving, shy, sentimental. The latter mode, Turner argued, interprets the real self as the one that breaks out of the role. In that spirit, Sharon Hodde Miller, a contemporary critic of church modesty rules, declares, “A woman’s breasts and buttocks and thighs all proclaim the glory of the Lord. . . . Modesty is an orientation of the heart, first and foremost.”

• • •

Norms change even if some hold out against the ethos of authenticity in informality. Once enough people show up in casual attire, the threshold drops. Expectations shift to the informal, perhaps even to a vague code of informality itself. Come to the office in a three-piece suit or shake a hand instead of giving a bro-hug, and onlookers’ responses may well discipline you back to informality. (The grief President Obama got for wearing “mom jeans” suggests there is a wrong way of being informal.) Twenty-first-century informality seems not to have stemmed the flood of manners and advice books, which now come with suggestions of looser, less deferential norms. The trend toward casualness has not exhausted itself.

Some scholars argue that the informalization of the twentieth century proceeded only because Americans had, by the early 1900s, so well imbued themselves and their children with the discipline that the teenage George Washington rehearsed. The enforcement of external rules could be relaxed because people had learned to control themselves. Self-governance made the precisely choreographed manners once needed to maintain peace in royal courts unnecessary.

Indeed, our contemporary informality may depend on much tighter internal control than formality did. An employee can put her feet up and share a beer with her boss, but just how far can she go in speaking her mind? It may be harder to do what is proper when what is proper is so flexible.