At the time, the event that took place in Boston on the night of December 16, 1773 was not called the “Tea Party.” For more than 50 years, if it was mentioned at all in print, it was usually as “the destruction of the tea.” Bostonians never celebrated it as they did their triumphs over other British measures. Patriot leaders cited the Indian disguises worn by some in the boarding parties in order to deny responsibility for the affair and claim it was the work of outsiders.

By mid-1774, after Britain closed the port as punishment and a British army once again occupied the town, it was hardly politic to claim credit for it. Nor, as rebellion turned to revolution, did it fit the pose patriots assumed as the victims of British aggression. In Paul Revere’s classic engraving of the Boston Massacre, a line of British soldiers fires on a group of hapless civilians at the command of their officer, and in the depiction of the Battle of Lexington the soldier James Pike carved on his powder horn, the men on one side of the iconic Liberty Tree are “Regulars, the Aggressors” and on the other side “Provincials Defending.” The carefully planned, disciplined action of a hundred and more men boarding three ships docked at Griffin’s Wharf, hoisting 342 heavy chests of tea out of the holds, hacking them open with axes, and dumping their contents into the harbor could hardly be portrayed as defense against aggression.

Since then, “owning” the Tea Party has been a political act. Partisans of today’s Tea Party movement have seized on it as a symbol of defiance of government, claiming the founders were united in opposition to taxation (with or without representation), government regulation, and spending. But Tea Party advocates seem indifferent to the original event. When Glenn Beck devoted an episode of his since-cancelled Fox News show to celebrating Samuel Adams, one of the Boston Tea Party organizers, he was mainly concerned with depicting Adams as a neglected Christian patriot. And when Sarah Palin spoke on the Boston Common in 2010, she had nothing at all to say about either the deliberations in Old South Meeting House that set the stage for the event or about the action itself at the waterfront.

The reluctance of today’s Tea Party to explore the history is not surprising given the thrust of recent historical scholarship on the resistance movements that led to the American Revolution. In the newly released Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America, Benjamin Carp demonstrates that the Tea Party and Boston’s revolutionary culture emerged in good part from the influence on elites of what conservative contemporaries dismissed as the “lowest ranks” of the people or “rabble.” And in The Freedoms We Lost: Consent and Resistance in Revolutionary America, Barbara Clark Smith, extends this argument about popular influence to the colonies as a whole. Moreover, she shows that a “Patriot coalition”—in contrast to the present-day Tea Party—sought “public power to counteract the coercions of the market.”

By any historical measure, the destruction of the tea was of major importance, the culmination of a near decade of resistance and the impetus for Parliament’s punitive acts, both catalysts of the movement that led to independence in 1776. It was an act of defiance, but defiance of whom, by whom, and to what end?

There have always been conflicting claims to the memory of the event. Throughout the nineteenth century, Boston’s Brahmins—the owners of ships, banks, and textile mills who appointed themselves keepers of the past—distanced themselves from the Revolution’s radical activism, especially after it was appropriated in the 1830s by nascent journeyman trade unions demanding a ten-hour working day and by radical abolitionists such as Wendell Phillips. To conservatives the event became “the so-called Boston Tea Party,” just as the five working-class victims of “the so-called Massacre” were “ruffians” who did not deserve the honor of a statue near the Common. In 1846 Nathaniel Currier, soon to join Currier & Ives, used the dignified name “The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor” for his popular lithograph, but to overcome viewers’ possible bewilderment about his portrayal of men in bizarre Indian garb destroying private property, he filled the foreground with hundreds of properly dressed Bostonians on Griffin’s Wharf, cheering them on.

At Boston’s centennial observance of the event in 1873, Robert Winthrop, former congressman and longtime president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, condemned the Tea Party “as a mere act of violence.” He went so far as to suggest that the founders had no part in it: “We know not exactly . . . whether any of the patriot leaders of the day had a hand in the act.” And in 1876, amidst a new wave of labor agitation at the centennial of American Independence, he called for a renewal of “the spirit of subordination and obedience to law.” The same year at a celebration marking the last-minute rescue of Old South Meeting House from the wrecking ball, Winthrop shed no tears over the near loss of the building famed as the place where the Tea Party action began. But Phillips, by 1876 a labor radical, proposed that it be preserved as a “Mechanics Exchange,” referring to the name artisans had taken for themselves in the Revolutionary era. “It was the mechanics of Boston that threw the tea into the dock,” he proclaimed, and “held up the hands of Sam Adams,” sending him to Philadelphia and the Continental Congress. “The men that carried us through the Revolution were the mechanics of Boston,” he said. Phillips’s interpretation of the relationship of Samuel Adams to the mechanics ran counter to the view held by conservatives at the time of the Revolution and since then by historians of varied persuasions. Phillips defied the notion that the Revolution belonged exclusively to the founders, while working people did as they were told.

He was ahead of his time. Early in the 1900s the progressive school of historians—including Charles Beard, Carl Becker, and J. Franklin Jameson—took issue with the prevailing view of the Revolution as essentially a struggle with Britain over constitutional matters, instead stressing the role of competing classes and economic interests. But for all their emphasis on internal change—in Becker’s aphorism it was not only a struggle for “home rule” but for “who shall rule at home”—the progressives for the most part were inattentive to popular movements. Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.—whose 1918 The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution Beard welcomed as “the most significant contribution that has ever made to the history of the American Revolution”—saw “merchants as a class” directing events, while mechanics, whose “brains were in their biceps,” were manipulated by the “propaganda” of Samuel Adams, “the deus ex machina” of the Revolution in Boston.

From the 1960s on, historians challenged such accounts in markedly different ways. Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood, disdainful of the explanatory power of propaganda, offered an “ideological” interpretation of the Revolution, which took for granted that the ideas disseminated by those on top were both instrumental and widely shared by those below. The “New Left” historians, Staughton Lynd and Jesse Lemisch best known among the first wave, took another approach. Inspired in part by the success of the English cultural Marxists George Rudé and E.P. Thompson in recovering “the crowd” in history, they explored the agency of American seamen, mechanics, and rural laboring classes in shaping the Revolution. Other scholars uncovered the active role of African Americans, women, and Native Americans.

The social historians’ concern with “politics from the bottom up” has unfortunately been lost in recent best-selling biographies celebrating the character of the founders. Still, Phillips’s comment about the mechanics who “held up the hands of” Samuel Adams remains and it goes to the heart of questions about the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution, questions rich with present-day implications: whose party was it? And who was leading whom?

One of the many virtues of Benjamin Carp’s assiduously researched, very readable book is that he unfolds a dramatic narrative from the vantage points of a wide range of participants. In England we watch events from the point of view of the British political establishment and the powerful East India Company. In the colonies we see them through the eyes of consumers of tea and political activists in the seaport cities. Within Boston, Carp portrays a conflict between loyalists and patriots, who include artisans as well as merchants.

In his analysis the resistance movement that began in the mid-1760s was a “loose coalition” led by “men like Samuel Adams, John Hancock and Ebenezer Macintosh.” Hancock was the richest man in Boston, highly influential among merchants; Adams, in 1773, moved only as part of the Committee of Correspondence and the North End Caucus, organizations heavy with professionals, merchants, and artisans of the middling sort; Macintosh was a poor shoemaker who in 1765 led several thousand in street demonstrations against the Stamp Act. In Carp’s reading of the Tea Party, unlike Schlesinger’s, merchants appear divided, and the laboring classes are actors rather than a mindless “mob” acted upon by others.

Carp argues convincingly that the issues at stake in the tea action were far more layered than current Tea Party activists recognize. Taxation by Parliament—in which colonists were unrepresented—opened a hornet’s nest because the British had shifted from one tax to another between 1765 and 1773, and one could not help but wonder what they would tax next. Would it be land? The major target of patriot wrath, however, was the East India Company, a corporation chartered by Parliament, the largest and most powerful in the British Empire. With 17.5 million pounds of tea glutting its warehouses, the Company stared at ruin, the British treasury faced the loss of a third of its customs revenue, and the many members of Parliament who owned stock in the Company confronted the loss of their investments. For the British establishment, the Company was too big to fail. To bail it out, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which granted the Company a monopoly on the sale of tea in the colonies—eliminating American merchants as middlemen—as well as a rebate on the tea tax that would allow it to lower the price of tea and make it difficult for patriots to sustain a boycott. For American merchants this monopoly created another slippery slope: what imported commodity would be next? And artisans, buoyed by patriot campaigns to boycott British imports and “buy American,” wondered which British manufactured products would soon be protected.

Adding insult to these pocketbook injuries, the Tea Act revived the raw issue of profiteering from public office. The agents appointed to sell the tea (at 6 percent commission) included the two sons of Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson, whose salary of £1,500 would be drawn from the tea tax and who also happened to have an investment of £4,000 in East India Company stock. Moreover, the Company had acquired an odious reputation as the brutal ruler of the Indian province of Bengal, where tens of thousands had perished in a recent famine. The “nabobs” had “stripped the miserable Inhabitants of their Property,” an American newspaper writer charged. Would American colonists suffer the fate of Bengal?

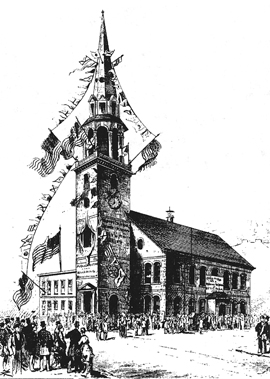

Bostonians streaming into an eleventh-hour meeting at Old South Meeting House in 1876 to protest the planned demolition of the building where the idea for the Tea Party was born. / Courtesy of Old South Meeting House / Old South Association

Bostonians streaming into an eleventh-hour meeting at Old South Meeting House in 1876 to protest the planned demolition of the building where the idea for the Tea Party was born. / Courtesy of Old South Meeting House / Old South Association

With so many threats aroused, resistance to the Tea Act in Boston was broader and more furious than to any previous British measure. The relatively small number of men boarding the three tea ships—Carp estimates a hundred to 150—can be misleading. Their action was preceded by three massive meetings of the “body of the people” on November 29 and 30 and December 14–16, 1773, at which the leaders dropped the property and age requirements for voting in official town meetings. The results were unprecedented. Boston had a total population of about 16,000 (of whom roughly 600 were African Americans, all but a handful enslaved). In 1773 there were between 2,500 and 3,000 men 21 or older, the legal age. The property requirement, while relatively small, kept large numbers from voting. In the years before the Revolution, the highest turnout at town meetings was for the spring election of delegates to the Massachusetts Assembly, which, on average, attracted about 500 voters. Faneuil Hall, the site of official meetings and then less than half the size of the present building, was “capable of holding 1200 or 1300 men,” Samuel Adams wrote. But meetings called for the body of the people could be held only in the largest building in town, Old South Meeting House, men jamming the pews, aisles, vestibules, and balconies. Adams wrote privately of an attendance of “5000, some say 6000 men” and of “at least 5000,” while one conservative guessed 2,500. The final meetings were swelled by country people from five surrounding towns, crowds overflowing into the streets. The meetings at Old South were thus five to ten times larger than the biggest official town meetings.

No previous indoor political meeting had been as large as the three that precipitated the destruction of the tea, and none was attended by the same mix of social classes. At a standard town meeting, the voters were merchants, shopkeepers, professionals, and master artisans of the “middling sort” who employed journeymen and apprentices. The first “body” meeting, the very class-conscious Hutchinson wrote, straining to be exact in his report to his superiors in London, “consisted principally of the lower ranks of people and even journeymen tradesmen were brought to increase the number and the rabble were not excluded, yet there were divers Gentlemen of Good Fortune among them.” A few years later, remembering the meetings as whole, Hutchinson still conveyed a sense of shock: “It was composed of the lowest as well, and probably in as great proportion, as of the superior ranks and orders” and “all had an equal voice.” In his lexicon, the lowest ranks were journeymen, poorer artisans, and petty shopkeepers, and the rabble were apprentices, seamen, common laborers, and “Negroes and boys.” In the boarding parties, the proportion of artisans was even higher. Of the hundred or so men whose presence on the ships Carp can verify, “almost two thirds were artisans in various stages of their career.” Because they were “working men in a port town, the boarders knew their way around a ship’s deck.” And of all boarders whose ages are known, “more than a third were under 21.” Only a score of men designated in advance wore Indian disguises; the last-minute, self-invited majority had time only to blacken their faces with soot.

“Who says these artisans were merely following orders?” Carp asks. Since the Stamp Act demonstrations in 1765, they had shown time and again they were capable of taking the initiative in street actions, and they often knew each other, if not in their trades, through firefighting companies, drinking clubs, or militias. “It appears more likely,” Carp concludes, “that they destroyed the tea from their own political motives.”

After eight years of resistance, everyone, high and low, was conscious of the capacity of Boston’s lower ranks. Leaders had every reason to fear that the people would again take some sort of violent action—burn the ships, burn the tea, destroy the houses of royal officials or loyalist merchants, tar and feather customs officials, haul the consignees to the Liberty Tree for forced resignations. Since 1765 Boston crowds had perfected all such tactics. Thus from the vantage point of the leaders, they were bringing “the people out of doors”—the common term for those outside the formal body politic—literally indoors where they could be won over to carefully planned actions. But the lower ranks had good reason to believe that, by their militancy, they had forced their way into a political system that they were enlarging by their presence. This is the little-appreciated heritage of the Boston Tea Party.

Those returning to Old South day after day were more than spectators. They voted on motions and responded to speakers, applauding, hissing, shouting words of approval or disapproval. The issue was clear. The law required that customs on cargo be paid within twenty days of a ship’s arrival; the deadline for the first ship, the Dartmouth, was midnight, December 16. There was a near consensus among patriots that the ship should return to Britain with the tea. The principals were called before the meetings—the ship owner, the captain, representatives of the consignees, and customs officials—and asked if they would consent to such action. None would, and a hidebound Governor Hutchinson, the last resort, refused clearance for the ship. Ordinary people thus were being asked to sit in judgment of their betters, aware that their very presence made them indispensable. When, for example, John Rowe, a merchant of shifting loyalties, apologized for being part owner of a tea ship and asked “whether Salt Water would make as good Tea as fresh,” the crowd roared, and a conservative overheard a few men brag that “now they had brought a good Tory over to their side.” Among the lowest ranks who had never set foot in a town meeting, much less voted, gatherings where “all had an equal voice” were empowering. Among middling artisans it encouraged a growing sense of their political strength. By the spring of 1774, to take Carp’s story a little further, Dr. Thomas Young of the patriot inner circle could report that while the merchants were unreliable, patriots depended on “those worthy members of society, the tradesmen” who were “carrying all before them.”

At the tea meetings, Bostonians were acting out the political philosophy implicit in functioning as the “body of the people.” As T.H. Breen reminds us in American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (2010), that phrase came from John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, the tract justifying the English Revolution of 1688. Samuel Adams referred to “the reasoning of the immortal Locke,” and, as recently as March 1773, a Boston printer had brought out Locke’s “noble essay.” In a section entitled “Dissolution of Government,” Locke asked: if “on a thing of great consequence” the actions of the ruler were “contrary to or beyond that Trust the people had placed in him, . . . who so proper to judge as the Body of the People” whether the contract was broken? If the ruler declined the judgment of this ultimate body, “the Appeal then lies nowhere but to Heaven.” In the spring of 1775 at Bunker Hill, New Englanders carried into battle a flag emblazoned with the slogan “Appeal to Heaven.” A year later the Declaration of Independence would spell out this right to revolution as a last resort after a people had exhausted all other remedies.

In The Freedoms We Lost: Consent and Resistance in the American Revolution, Barbara Clark Smith offers a bold, compelling context for the give and take between elites and ordinary people in the Revolutionary era. Written over many years and based on a familiarity with a wide range of original sources and scholarship, her book explores the forms of action taken by patriots as well as their conception of government as a guarantor of the common welfare. The book thus speaks with unusual clarity to patriots’ underlying values, so little grasped by those who claim the founders for a laissez faire tradition. But it also speaks to issues deserving discussion among progressives, many of whom seem little aware of the popular movements of the era or else are at a loss to integrate them with strident claims for the founders. Smith traces how popular mass participation shaped elites before and during the Revolution, and how after the Revolution that participation was reduced to voting within the electoral system and thereby made less effective.

Smith’s reading of the era reverses the widely held view of the flow of politics from the top down and from the political centers out. “Understandings of Patriotism also circulated up,” she writes, which meant “from the parochial and the local into the official centers of political authority.” To look at the colonial resistance this way “is not to discount or ignore the acts of the prominent Patriots,” but few leading men “developed their political thinking in isolation. . . . On the contrary, the colonial elite, Patriot and Loyalist, were influenced at every step of their thinking by their own embeddedness in society. . . . They felt at every turn the ideas and activity of more ordinary men.”

Smith believes that historians, overly focused on voting as the almost exclusive measure of democratic participation, have missed the “surprising range of occasions” in the colonial era in which ordinary men, such as small property holders, “establish[ed] significant political agency” for themselves. “Many colonists,” Clark Smith tells us, “believed it essential to English liberty that laws be subject to popular scrutiny and consent after their passage by the legislature,” and not only before. They held that they had a right to “regulate” lawmakers and oppose the execution of laws, and agrarian protest movements frequently adopted the name “Regulators.” They exerted their presence in grand juries and trial juries, as spectators in the courtroom and at public executions, and above all in crowd actions that “not infrequently . . . laid claim to lawful status.” In Smith’s reading, “The entire legal system depended on the existence of a common ground of political participation on which riots took place.” Spectatorship—shorn of the “connotation of passivity”—was political.

Smith reckons that, throughout the colonies, “the Patriot movement of 1765–1776 was about the popular presence in execution of the law.” Colonists “harried tax collectors, coerced officials into resigning, tarred and feathered informers and customs commissioners . . . threatened and demolished houses [of royal officials] and destroyed tea to prevent duties being paid on it.” This interpretation “places the social and cultural commitments of ordinary colonists at the center of the resistance.” In the common historical account, the “end itself (defending liberty and eventually seeking independence) seems defined by political elites,” and the actions of the mass movements are no more than the means to achieve ends defined by others. In Smith’s vision “the presence of the people out of doors vitally defined the colonies’ resistance movement,” a breathtaking and illuminating claim.

Implicit in the forms of popular resistance to British measures—boycotts, non-importation and non-consumption agreements policed after 1774 by local associations—were the values people placed in community, mutual responsibility, and “neighboring.” They expressed a sense of social interdependence as they moved toward political independence. Patriot elites who assented to these practices, as opposed to Loyalist elites, acknowledged “the powerful presence of their social inferiors,” including “their capacity to appear in numbers in public, to act collectively ‘as the people.’”

During the war, from 1775 to 1780, this patriot coalition supported a “patriot economy” of self-sacrifice, limited profits, and controlled prices. But the postwar years revealed “fault lines along which Patriotism splintered.” In Massachusetts, when farmers in dire straits resorted once again to conventions and extralegal actions, elites turned to repression. Samuel Adams, before 1776 a champion of the people’s right to dissent from the execution of the law, now denied the same right to agrarian radicals following Captain Daniel Shays, among other leaders. As “we now have constitutional and regular government” in the state, Adams argued, “and all our men in authority depend upon the annual, free elections of the people,” there would be no further need for “any self-created conventions or societies.”

“When government originated in the people,” as it did as a result of the Revolution, Smith concludes this part of her argument, “there was less space for people to act as ‘the people.’ Representation became the heart of political life and the focus of political contests.” In British North America, there had been space for “consent after the fact . . . . In the aftermath of the Revolution, that space would dramatically contract.”

Smith doesn’t try to upend our every understanding of the Revolution or make it out to be an “unalloyed loss,” but her argument challenges adulatory biographers of the great men of the era. She also challenges historians of popular movements who need to pay far more attention to these movements’ effect on elites. History from the bottom up was never intended to be history only of those at the bottom. The book invites analysis of how, in a time of great upheavals, elites become a governing class that limits popular majorities yet finds ways to accommodate them.

Going beyond these changes in “political forms,” Smith explores attitudes about the proper ends of government. Modern day Americans, she writes, have lost an awareness of the patriot coalition’s commitment to locating freedom “precisely in a popular capacity to determine the use and value of property within a framework of social purpose and human need.” Young Samuel Adams, she reminds us, defined “public virtue” much as the pseudonymous “Cato” had: “one Man’s Care for Many, or the Concern of every Man for All.” As editor of Boston’s Independent Advertiser in 1748, Adams reprinted passages from Cato’s Letters, essays by two English philosophers widely read in the colonies. “Every Man has a Right and a Call to provide for himself,” Cato wrote, but “he performs [this duty] subsequently to the general Welfare, and consistent with it. The Affairs of ALL should be minded preferably to the Affairs of One.” Adams, Smith writes, reminded the wealthy that “life was not merely a market, and they were not in fact entirely insulated from the judgments of their neighbors.”

Do we have any way of knowing Bostonians’ underlying values in 1773? One way might be to thumb the pages of the official Boston Town Records in the decades before the Revolution to see the numerous ways the town-meeting government assumed responsibility for the “many.” So-called “overseers of the poor,” who were for the most part men of some wealth, distributed direct relief ward-by-ward to a huge number of poor widows in their homes. For the destitute, the overseers maintained an almshouse and a workhouse, both admittedly grim places. The selectmen also authorized a town granary to provide grain at set prices in times of dearth. To put the numerous unemployed to work, the town sponsored a “Manufactory House” of spinners and weavers managed in the 1760s by William Molineux, a leading Tea Party organizer. And in 1774, when Britain closed the port and massive unemployment loomed, the town meeting voted at “this Time of general Calamity” to put people to work: to erect a wharf, build ships, pave the streets, or undertake “any other public Work.” To meet such social responsibilities, Bostonians supported taxation—as long as it came from either their own participatory town meeting or the Massachusetts Assembly they voted for. Samuel Adams was no less popular because he made his living for eight years as one of the town’s four tax collectors. (His father, not he, was a brewer.)

The town records also suggest Bostonians took for granted that their government should regulate the quality of manufactured goods. The town appointed Ebenezer Macintosh—the shoemaker at the Tea Party—one of several “sealers of leather” and selected a score of other artisans as “inspectors” or “surveyors” of lumber, shingles, hemp, etc. From time immemorial the town set the “assize” of bread, establishing the size, weight, and price bakers might charge. Arguably, citizens registered their assent to regulating the market every time they bought a loaf.

In 1780 Bostonians spelled out the philosophy underlying such actions when, after much debate, they voted in the town meeting 847-0 to ratify a new constitution for the aptly named Commonwealth of Massachusetts, drafted principally by Samuel and John Adams. “Government,” Article VII explained, “is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men.” Earlier Cato had asked, “is it a crime to be rich?” and answered, “Yes, certainly at the publick Expence, or to the Danger of the Publick.” Cato argued, “Power was needed when men tried to put a whole Country in Two or Three people’s Pockets.” In 1773 the body of the people in Old South, founders all, would have cheered his answer.