In 1842, the Chinese government capitulated to Western military power and signed the Treaty of Nanjing. The treaty handed over Chinese sovereignty to Great Britain, prying open China to the vicissitudes of the global market and ending the country’s ban on the import, production, and consumption of opium. The empire had struggled for decades to control the substance, trying everything from appeals to Confucian values to a Reaganesque “War on Drugs.” Some even called for a death penalty. With China’s markets again open and its public health measures overturned, opiate use soared. By 1900, 10 percent of the Chinese population used opium and 3 percent were addicted. (For comparison, the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimates that the prevalence for all drugs worldwide currently is about 5 percent.)

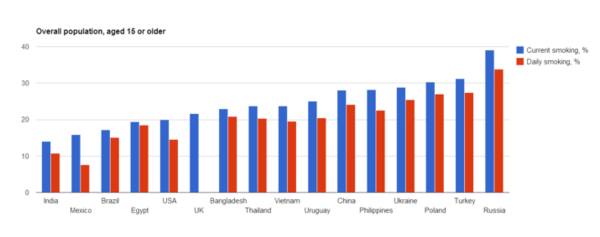

Today the global tobacco epidemic is exhibiting a similar trend. According to the World Health Institute, “nearly 80 percent of the world’s one billion smokers live in low- and middle-income countries.” Multinational corporations are seeking their own Treaty of Nanjing: they are using free trade agreements to usurp national sovereignty and stymy economic development. Tobacco kills six million people each year, and if current trends continue, it will kill one billion people in the twenty-first century.

Enter the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This free trade agreement between the United States, Canada, and ten Asian-Pacific countries is currently in negotiation, but has been dragged out far past its deadline (and slowed by the President’s lack of “fast track” authority). The TPP covers 40 percent of U.S. exports and imports and may well be the most under-reported story this year. The agreement, which would allow corporations to sue governments directly in an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), will put developing countries in the hands of multinational corporations. The potential for abuse is obvious from cases like Chevron vs. Ecuador, in which Chevron is trying to evade a domestic court ruling that it owes $18 billion for mass contamination of the Amazon. A three-person tribunal of lawyers can now choose to override the decision of the Ecuadorian court.

The ISDS will also be insidious in cases like tobacco: opening countries to foreign markets for development can end up compromising public health.

Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Gary A. Giovino, et al. The Lancet, August 2012.

Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Gary A. Giovino, et al. The Lancet, August 2012.

Gunboat Diplomacy

In the face of international trade regulations, tobacco companies have used a tactic reminiscent of nineteenth-century British corporations in China: get the government to do the dirty work. In 1990, the GAO found that “the U.S. government provided assistance in removing [foreign-imposed trade] barriers.” The strategy was simple. The companies threatened to use Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, known as Super 301, to put countervailing tariffs on countries that did not open their markets to the multinational tobacco corporations. Within a year, the rate of tobacco use increased by 10 percent in affected countries. Following public outrage, a Doggett amendment has been inserted into every budget bill since 1997. Clinton signed an executive order in 2001 to prevent executive branch resources from being used to foster tobacco exports.

Now tobacco companies are working to weaken national regulations. In 2004, 168 states signed onto the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).The treaty is binding, but has no enforcement mechanism. It includes air-quality regulation, ingredient regulation, a ban on marketing, and excise taxes. Although the United States has signed the treaty, it has not ratified it.

Because the treaty sets minimum standards, Chris Bostic, Deputy Director for Policy at Action of Smoking and Health (ASH), told me that the industry has “gone after any country that has pushed the norm.” They use trade supranational trade courts—which are notoriously loath to put environmental, health, or labor standards over a buck—to strike down regulations on tobacco.

In 2009 Uruguay mandated that 80 percent of the front and back of a cigarette pack be covered by visual warnings. They also banned colored branding, such as Marlboro “Reds” and “Yellows,” which companies had been exploiting since the FCTC banned the use of qualifiers—lite, low, or mild—intended to imply safety. Such graphic visual warnings may be useful to help prevent children from smoking. A recent study published in Pediatrics finds that 68% of children aged 5 or 6 in low- and middle-income countries can identify at least one cigarette brand logo. Other studies show that visual warnings are more effective with children and are especially crucial in developing countries where portions of the population may be illiterate.

Developing countries are faulted for their ineffective governance, but free trade strips them of the power to regulate and protect public health.

In response to Uruguay’s mandate, Philip Morris is currently suing Uruguay through a bilateral investment treaty between Uruguay and Switzerland. Uruguay, which has an annual GDP less than half of Phillip Morris’s annual sales, planned to back down until Mayor Michael Bloomberg offered to pay their legal defense fees. Among other things, this case is aimed at discouraging other countries from moving forward with similar regulations.

Australia is facing a similar case. The Australian government passed the strictest labeling law yet in 2011, requiring packets to include not only graphic health warnings but also “plain packaging” regulations, meaning that the packets would be a drab green color and the company name would be written in a font chosen by the government. Companies would not be able to brand their products. Tobacco companies sued the government domestically, but in 2012, the High Court upheld the legislation. Now five countries are suing Australia at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Ukraine initiated a lawsuit, even though Ukraine doesn’t sell tobacco, and British American tobacco confirmed that it is helping to payUkraine’s legal fees. In addition, Phillip Morris is using a bilateral investment treaty between Hong Kong and Australia to sue directly.

Already the Australian lawsuit is having its intended effect—what lawyers call “legal chill.” New Zealand was prepared to institute a similar plain packaging bill but has tabled the plan until the Australian case is decided. The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the Koch Brothers have lined up to derail a plain packaging case in the United Kingdom.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership

The TPP, which is still under negotiation and may be ratified this year, will be one of the largest regional trade agreements and will likely be a model for other agreements, most notably the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). The TPP treaty isn’t about trade; of the twenty-nine chapters, only five deal with traditionally trade-related subjects. Australia’s regulations, for instance, did not discriminate based on trade, but the companies are still suing. The rest of the treaty is about harmonizing regulations across member countries, “and the best way to harmonize regulations is to get rid of them,” said Bostic.

Under the TPP, if a three-member ISDS tribunal that oversees disputes decides in favor of a company, the tribunal can order taxpayer compensation. The decision cannot be overturned by national governments. ISDS includes some 3,000 bilateral trade treaties and has existed since the 1950s, but it was only in the last decade that corporations realized the power of ISDS. Since 2000, the number of investor-state cases has increased ten-fold. Companies like Phillip Morris do what is called “treaty shopping,” searching for a bilateral-investment treaty by which they can sue a country. With TPP as the model, they can be far freer with their suits.

Ben Beachy, Research Director at the Global Trade Watch arm of Public Citizen, told me “the scope of the policies being challenged is egregious. It affects not just tobacco, but energy policies, health policies, and court decisions. It’s a really alarming system and one we keep thinking we’ve seen the limits of how extreme these cases can be, and with each case we’re more surprised.”

Because of TPP’s vast implications, anti-smoking groups are trying to get an exemption protection inserted into the treaty. The U.S. government has drafted not a full exemption but rather a weak “safe harbor” provision, which would not protect governments from lawsuits forwarded by tobacco companies. But even the safe harbor was too strong for tobacco lobbyists. In August, the moderate proposal lobbied for by the United States was decried by Mayor Bloombergas “weak half-measures at best.” Since then, Malaysia has put forward a full exemption (meaning that nothing in TPP will apply to tobacco) that protects governments from corporate lawsuits. If the treaty does not include a carve-out, Big Tobacco will swoop in on developing countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, an “epidemic waiting to happen,” said Bosnic. The effects would be catastrophic.

Arrested Development

These cases will have big implications not just for public health but also for international development. Smoking encumbers developing countries by burdening public health systems, cutting off productive years, and diverting income from more productive uses.

One study in Bangladesh finds that 9 percent of all deaths in the country could be attributed to tobacco and that 29 percent of all inpatients aged thirty and above suffered from tobacco-related illnesses. Another study in Bangladesh finds that male smokers spend “twice as much on cigarettes as per capita expenditure on clothing, housing, health and education combined.” A study in Jamaica finds that people who suffer from tobacco-related illnesses can spend up to 50 percent of their annual income on health care.

A recent study published in the Lancet finds that the most effective way for developing countries to raise revenues and reduce the consumption of tobacco is high excise taxes. However, in the future, when countries try to pass such excise taxes, it is very likely companies will use any means necessary to create an environment of fear and prevent their implementation, including possibly an ISDS case.

Here we see the failure of the neoliberal position; we must accept the TPP and other free trade agreements so that poor countries may develop, but in doing so they must open markets to tobacco. Developing countries are faulted for their ineffective governance, but free trade strips them of the power to regulate and protect public health.

Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengalese poet, wrote of the Opium wars that, “In hopelessness, China pathetically declared: ‘I do not require any opium.’ But the British shopkeeper answered: ‘That’s all nonsense. You must take it.’” History rhymes again.