On my first trip through Afghanistan in 1978, I was met with the richness of agricultural production at a time when the country had achieved food security for a population of 15 million. My trip was in early spring, when pomegranates, apricots, cherries, figs, peaches, grapevines, and mulberries had started to bloom, and wheat was sprouting. U.S. and Soviet aid had been pouring in since the 1940s in an effort to influence Afghan policies, opening up irrigation projects on thousands of acres of land in the provinces of Helmand and Kandahar.

In the late 1970s, the country was famous as an exporter of fresh and dried fruits, of karakul skins, carpets, and cotton. The northern city of Kunduz, surrounded by fertile agricultural land producing cotton, wheat, rice, millet, fruits, and other crops, was known as “the hive of the country.” There, the Spinzar Cotton Company, built in the 1930s, employed around 5,000 people full-time. It was financed by the national bank, Bank-i-Melli which acted as an investment bank. In the west, the city of Herat was known as the “breadbasket of Central Asia.” In the south, Kandahar acted as the main trading center and a market for fresh and dried fruits, grains, sheep, wool, cotton, and tobacco. The city had plants for canning, drying, and packing fruits, and for manufacturing woolen cloth, felt, and silk. Afghanistan was dignified if poor, at peace internally and with its neighbors.

Today, Afghanistan’s economy is a house of cards. It will likely collapse when foreign combat troops leave and as aid continues to fall. It is estimated that Afghanistan will need at least $8-$12 billion of economic and military aid a year for the next decade to recover. Even if it constitutes just a pittance compared to the cost of the war, this amount is not at all realistic. Moreover, although the government plans to build self-sufficiency during the transformation decade, IMF projections show that, unless there is a sharp shift in policies, the country will remain dependent on aid until well beyond 2025. What happened, and what can be done to return Afghanistan to a peaceful, productive, and stable state?

• • •

Two weeks after my trip, the bloody communist coup d’état in April 1978 led to the Saur revolution. In December 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, which would become the last political battleground for the Cold War. The mujahedeen—a diverse group of “freedom fighters” including radical Islamic groups that received heavy financing from the CIA—announced a jihad against the Soviets. The Soviets fought mostly in rural areas, laying 10 million landmines and destroying agricultural life and production. At the same time, Afghans began producing natural gas and exporting it to the Soviet Union. In the process, the share of mining in total exports increased and government revenue rose.

Kabul was destroyed both physically and economically by the brutal civil war that followed Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and continued among different mujahedeen after the collapse of the Soviet-backed government in 1992. Opium production and trade fuelled the civil war and weakened the Kabul government. The Taliban took power of Kabul in 1996 and served as de facto rulers of the country until the end of 2001 when they fled the city, almost three months after the start of Operation Enduring Freedom. By then, arms trafficking and smuggling were widespread, and the only domestically produced exports were narcotics and some timber and gemstones.

The promises made by President Bush in April 2002 to help rebuild Afghanistan in the tradition of the Marshall Plan created high expectations among the Afghan population after the rout of the Taliban and the Bonn Agreement of December 2001. But despite costly international efforts, Afghanistan has relapsed into conflict and become one of the most aid-dependent countries in the world. The failure of peace negotiations with the Taliban, the upcoming presidential elections in April 2014, and the impending complete withdrawal of U.S. and NATO combat troops by the end of this year have contributed to uncertainty and instability in the country. Meanwhile, the population has grown to 33 million (from around 23 million in 2002), and the economy remains highly dependent on drugs, imports, and aid.

Afghanistan is not unique, of course. The success rate of peace transitions in countries torn by civil war since the end of the Cold War is dismal: roughly half the countries that embarked in a multi-pronged transition to peace involving security, political, social, and economic reconstruction—either through negotiated agreements or military intervention—have reverted to conflict within a few years. Of the half that managed to maintain peace, a large majority ended up highly dependent on foreign aid. What can the history of the last two decades teach us about how to improve international assistance to Afghanistan and to other countries coming out of conflict in the Middle East and North Africa?

One thing that recent history teaches us is that, because economic reconstruction takes place amid the multifaceted transition to peace, it is fundamentally different from development in countries not affected by war. Economic reconstruction has proved particularly challenging because Afghanistan must reactivate the economy while moving away from the economics of war—that is, the underground economy of illicit activities (drug production and trafficking, smuggling, arms dealing, extortion,etc) that thrives in situations of war and makes the establishment of governance and the rule of law extremely difficult. To succeed, economic reconstruction requires peace-building activities like the reintegration of former combatants, returnees, and other conflict-affected groups into productive activities, as well as rehabilitation of services and infrastructure. As John Maynard Keynes argued at the end of World War I, the economic consequences of building peace are high. The imperative of peace consolidation competes with the conventional imperative of development, putting tremendous pressure on policy decisions, especially budgetary allocations. Because there cannot be economic stability and long-term development without peace, it follows that, to avoid a relapse into conflict, peace should prevail as the main objective at all times—even if it delays the development objectives.

Another thing we learned from recent history is that economic policymaking in war-torn countries at low levels of development requires a simple and flexible macroeconomic framework. But the fiscal and monetary framework established in Afghanistan early on by the Minister of Finance—supported by only a few other cabinet members and adopted by decree since there was no legislative body until the parliamentary elections of 2005—was neither simple nor flexible. The independence of the central bank and the “no-overdraft” rule for budget financing adopted—policy components that make sense for countries in the normal process of development—deprived the government of any flexibility to provide subsidies or other incentives necessary for carrying out peace-related activities. At the same time, a simpler framework would have required less foreign expertise (reducing the distortions created by such presence) and restricted the opportunities for mismanagement and corruption among uneducated and low-paid civil servants.

The restrictive monetary and fiscal framework—in conjunction with a dogmatic belief of the economic authorities and their foreign supporters in trade liberalization, privatization, and private sector–led development, severely restricted the role of the state in reactivating investment and employment. Moreover, donors channeled about 80 percent of their aid through NGOs or U.N. agencies rather than through the government budget and according to government priorities. As an example, the Spinzar cotton company, by then a state-owned enterprise, could have been part of a government project to reactivate the cotton sector but was put up for privatization instead.

Not every aspect of the macroeconomic framework failed. The exchange rate policy worked well. The Minister of Finance opted to introduce new afghani bills issued by the central bank (Da Afghanistan Bank) rather than adopt the dollar or another foreign currency as the International Monetary Fund recommended and as other countries emerging from war often do to help stabilize their economies. In a currency exchange supported by the U.S. Treasury that began in October 2002 and was completed in only four months, the afghani became an important symbol of sovereignty and unity, restoring confidence in the domestic currency.

But a stable currency was not enough to reactivate production. Perhaps the most serious mistake was the neglect of the rural sector—on which roughly 75 to 80 percent of the Afghan population depends. Efforts to move the economy directly into higher productivity through commercial agriculture were misguided since it takes time to build infrastructure. Instead, the government should have used aid to provide subsidies and price support mechanisms to promote subsistence agriculture. Such measures would have improved the livelihoods of the large majority and given them a stake, however small, in the peace process.

The neglect of the rural sector drove production away from licit agriculture to drugs. Without other viable options, farmers increasingly turned to growing poppies. They got support from traders who provided credit and technical advice for future production, bought the opium in situ, and shared the risks. Drug production took the best available land, replacing food crops and necessitating large food imports. At the same time, drug production financed the insurgency, created insecurity, and promoted corruption among government officials and other stakeholders.

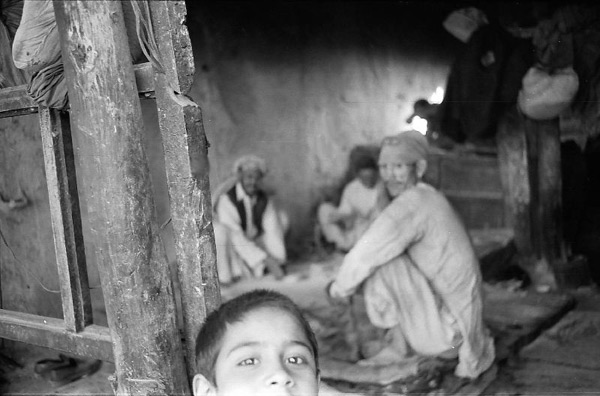

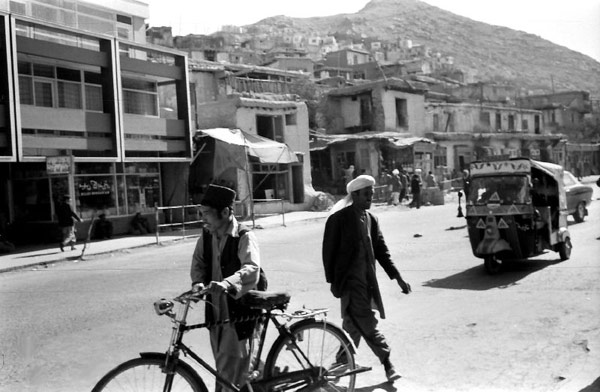

Photograph: nicksarebi

While this narrative may be familiar, few have looked closely at the way these developments have impacted Afghanistan’s economy today. In my forthcoming book Guilty Party: The International Community in Afghanistan I use original data from a variety of sources—the IMF, OECD, U.N. system (particularly UNCTAD, UNDP, UNODC), and several U.S. and Afghan government sources and extensive interviews—to develop a comprehensive picture of the Afghan economy. A few figures illustrate the magnitude of the problem.

Of the $650 billion appropriated by Congress for the war, as little as 10 percent may have been spent in Afghanistan itself. Although difficult to estimate with any degree of certainty, as much as 80-90 percent was probably spent in the United States: on war equipment and other procurement (including food) for our troops; on wages and compensation to military and civilian staff; on salaries and fees for our own consultants, contractors and law firms as well as for security companies that protect our people in Afghanistan; and on other imports, including food for the local population.

Of the $70 billion disbursed for Afghan reconstruction, over 60 percent—an amount equal to one third of Afghan GDP during this period—was used to establish and train the Afghan security forces. This allocation has created a security force that is fiscally unsustainable. Of the less than 40 percent allocated to non-security expenditures—including for governance and development, for humanitarian assistance, and for counter-narcotics purposes—the large majority benefited a small elite in the urban areas or has been wasted trying to rebuild infrastructure and other projects in insecure areas.

Despite the government’s remarkable efforts to bring in taxes and customs revenues in border provinces, domestic revenue increased only to 11 percent of GDP in 2012 from slightly over 3 percent in 2002. As a result, donors still cover over 60 percent of the national budget, not to mention off-budget development expenditure. An alternative way to highlight the large aid dependency is to note that donors finance most of the huge trade deficit—the excess of imports over exports—which amounts to over 30 percent of GDP. Misguided agricultural policies contributed to this deficit. Fruit exports, for example, fell to less than half, whereas food imports almost doubled from 2008 to 2011. While the country imported wheat, the area under cultivation dropped. Afghanistan also imported chicken meat, beef, rice, vegetable oil, tea, and even spices, products that could be easily produced within the country.

Despite the rapid economic growth—9 percent a year on average since 2002—that has led to frequent congratulatory remarks from different stakeholders, and despite the huge amount of aid the country has received relative to its size—75 percent of GDP on average since 2002 and 90 percent from 2009 to 2011 (the last year for which there is full data)—the Afghan economy remains small: it amounted to slightly over $20 billion in 2013. While income per capita in real terms almost tripled since 2002 to about $650 a year, it remains among the lowest in the world. Furthermore, construction and services were the most dynamic sectors. Since these sectors were geared to the large presence of foreign troops and civilian aid workers, their growth is not sustainable going forward.

Even the huge investment in security, especially after the 2009 surge, hasn’t paid off. Afghanistan is ranked as the most violent country in the 2013 Global Peace Index and in seventh place in the Failed States Index. Afghanistan is also ranked as the most corrupt country in the world in the Corruption Perception Index, together with North Korea and Somalia. In 2013, the Anti-Money Laundering Index ranks Afghanistan as the country most at risk for money laundering and terrorist activity, out of 150 countries in the index, displacing Iran from the first place.

Neither has the country’s position in the Human Development Index improved in relation to other countries. In 2012 Afghanistan was still ranked at the bottom 6 percent of the index, together with countries such as Mali where war was still raging. While many schools have been built, and attendance has increased significantly for both boys and girls, literacy remains below 30 percent. Basic health services coverage has increased to almost 60 percent of the population, but infant and maternal mortality remain among the largest in the world and life expectancy is still below 50 years of age.

Expectations for large foreign direct investment in mining and other sectors were also shattered. While these flows increased rapidly up to 2005 (mostly in construction and services), they have been anemic (averaging much less than one percent of GDP) since 2007 when security deteriorated, and fell to only half percent on average in 2011–2012.

The international community also failed to support Afghanistan in controlling the drug sector and providing viable livelihood alternatives for farmers. Opium production averaged 5,200 metric tons per year from 2002 to 2013—twice the average produced during the six years of Taliban rule when production was legal. Since 2002, Afghanistan produced on average 85 percent of global opium production.

The picture that emerges from these data is clear. Donor policy has failed to support a simple, well-thought, and integrated economic reconstruction strategy for Afghanistan and resulted in ineffective, fragmented, and wasteful aid. It is important to reassess the type of economic strategy that donors will support going forward and to shift policy to both minimize the high risk that Afghanistan faces of relapsing into civil war and the extraordinary aid dependency that afflicts the country.

In order to reduce the risks associated with investing in Afghanistan—which has led to the collapse of foreign direct investment since 2007—the government must create a system that benefits local communities and foreign investors alike. By restricting investment incentives exclusively to foreigners and domestic elites, the government has not only increased the potential for conflict with local communities but also neglected the vast potential of small farmers and micro-entrepreneurs who can contribute to steady growth and food security.

It was in this context that I have proposed the creation of “Reconstruction Zones” (see Rebuilding War-Torn States, Oxford University Press 2008). Reconstruction zones would consist of two distinct but linked areas to ensure synergies between them—an export-oriented zone and a local-production zone. In the export zones, the government would provide tax incentives, basic infrastructure and services, security, and a stable legal and regulatory framework for foreign and large domestic investors to produce exclusively for export. In exchange, investors would commit to train local workers, create employment by purchasing local inputs and services, improve corporate practices and local providers’ standards, facilitate the transfer of innovative and productivity-enhancing technologies, and establish links with local technical schools and universities. Export zones could produce commercial agriculture for countries in the Gulf, exploit natural resources, or assemble low-skilled manufacturing goods.

The local zones would focus on integrated rural development of agricultural and livestock products for the domestic market to boost food supplies and reduce Afghanistan’s exorbitant dependence on imports. The local zones would complement the government’s National Solidarity Program—a program that has succeeded in improving local governance but has lacked a mandate for income-generating activities. By providing a level playing field for all Afghans—men and women—in terms of security, social services, infrastructure, credit, and inputs (such as seeds, fertilizers, and agricultural machinery), the local zones would also help to bolster gender equality in the rural areas where women’s productivity is low and they have seen little progress in terms of gender rights.

These and other ideas for sustainable economic reconstruction—including direct cash payments to women for improving human development of their families, direct purchase agreements with global producers that support local farmers, and the creation of a development bank to finance activities in the rural sector—must be broadly debated if Afghanistan is ever to move into a path of peace, stability, and prosperity. As U.S. and NATO combat troops withdraw, we can continue to ignore the negative impact of our actions only at our own peril and at the peril of the Afghan people.