The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War

Craig Whitlock & The Washington Post

Simon & Schuster, $30 (cloth)

As one provincial capital after another fell to the Taliban with little to no resistance, establishment pontificators filled U.S. news outlets with criticism of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Some said the military should have stayed to finish creating a state that could defend itself. Others advocated redeploying troops to forestall defeat or defend a few cities. Some claimed that twenty years of war had created enough hope and opportunity—especially for Afghan girls and women—to justify indefinite continuation.

One way to justify failed and irredeemable wars—a method spawned by the Vietnam War and already evident in the days after the Taliban’s seizure of Kabul—is to attribute their disaster to errors of judgment rather than unchecked imperial ambition; to blame tactical mistakes rather than moral or ideological flaws. This produces a laundry list of historical “if only’s”: if only we had supported a different leader (or stuck with the one we had); if only we had bombed more ruthlessly (or less); if only we had sent in more troops faster (or fewer for longer); if only we had done more to root out corruption or learned more about the nation we invaded. “If only” we had done something differently, one way or another, we might have been victorious. These debates constitute much of what passes for “lessons learned.” Very few commentators, at least in the major corporate media, have dared to argue that no historical redo can offset the fact that the U.S. mission in Afghanistan was misbegotten and morally tainted from the outset.

An exception to this trend is Washington Post reporter Craig Whitlock, whose recent book, The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War (2021), draws evidence from interviews with some 1,000 people who participated in the war, including U.S. military officers, officials, aid workers, and Afghan leaders. About half of these oral histories were collected by the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) for a “Lessons Learned” project. Yet it took Whitlock three years of Freedom of Information Act requests and two federal lawsuits to force the public disclosure of these documents from the very agency charged by Congress to provide accountability for the resources the public expended on its longest war. The book also draws on interviews conducted by the U.S. Army and the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, as well as thousands of once classified memos written by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld to his subordinates (so many of Rumsfeld’s white-paper queries and admonitions piled up on their desks they called them “snowflakes”).

In late 2019 Whitlock and his colleagues at the Washington Post began writing about these documents, dubbing them the “Afghanistan Papers.” The name was intended to remind people of the Pentagon Papers, a 7,000-page top-secret history of the Vietnam War leaked to the press in 1971 by former government official Daniel Ellsberg. Like the Pentagon Papers, the Afghanistan Papers expose two decades of war-related deceit by multiple presidential administrations of both parties. Both sets of documents demonstrate that most U.S. leaders were pessimistic about the prospects for victory even as they repeatedly lied to the public and Congress by expressing faith in the war’s progress. Indeed, Whitlock makes a convincing case that “many senior U.S. officials privately viewed the war as an unmitigated disaster.” One of them, Army Lieutenant General Douglas Lute, the White House “war czar” under Presidents Bush and Obama, reports: “We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking.”

Even Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld privately conceded doubt and ignorance. At press conferences he mocked any journalist who questioned official claims of success or asked if Afghanistan might become a Vietnam-like “quagmire.” Yet, just weeks into the war, Rumsfeld wrote “snowflakes” to aides expressing concern that the U.S. mission was unclear and “drifting,” and that Americans in Afghanistan might end up “being as hated as the Soviets were.” By the end of 2003, Rumsfeld issued a classified complaint that he had “no visibility into who the bad guys are” in Afghanistan. He did not know whether they were Taliban fighters, or if they had slipped across the border to Pakistan like so many members of al-Qaeda; if they were the private militias of warlords, or opium traffickers, or leaderless local insurgents enraged by the U.S. occupation. How, then, could any of these “bad guys” be distinguished from the civilians whose political support was essential to the U.S.-backed government in Kabul?

American ignorance about Afghanistan was as pervasive as it was sixty years prior regarding Vietnam—but that was not the cause of failure and defeat in either country. In both cases U.S. officials had ample evidence to deter them from waging war, or at least to justify an earlier exit. Sharper officials even realized that the more lethal the military effort, the less likely they were to gain political legitimacy. They knew that military power alone could not win these wars; broad political support in both countries was the crucial necessity. Both the U.S.-backed government in Kabul and in Saigon always lacked this piece.

The mid-ranking military officers Whitlock quotes had more clear-eyed understandings than the higher-ranking generals that the war in Afghanistan was militarily unwinnable. No tinkering with tactics would have made a difference. “Nothing we do is going to help,” said Major Greg Escobar, an Army infantry officer, “until the Afghan government can positively affect the people there, we’re wasting our time.” Another Army major, Michael Capps, said, “You could be at double-arm interval over every square meter of Afghanistan [with military force] and still lose.” The war in Afghanistan, yet again, reminds us that military dominance does not guarantee political legitimacy.

Vietnam and Afghanistan have bested many of the greatest empires in world history. Vietnam expelled the Chinese, the Mongolians, the French, the Japanese, and the Americans. Afghanistan rid itself of Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States. These two countries defeated, among others, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.

Yet, despite all evidence that Vietnam and Afghanistan are “graveyards of empire” and private pessimism, U.S. leaders still expanded and prolonged the wars long after the violence had proven futile. Why were they willing to continue killing men, women, and children, and to imperil more of their own citizens, knowing that no clear-cut victory could ever be achieved?

It is a haunting question. A partial answer comes from the Pentagon Papers. In a 1966 memo written by John McNaughton, Assistant Secretary of Defense under Robert McNamara, he states: “The reasons why we went into Vietnam to the present depth are varied; but they are now largely academic. Why we have not withdrawn is, by all odds, one reason: to preserve our reputation as a guarantor . . . we have not hung on to save a friend, or to deny the Communists the added acres and heads.” As he later wrote in another memo, the overriding U.S. goal was “to avoid a humiliating defeat.” Yet, after those secret memos were written, we doubled U.S. troop levels, dropped 7 million more tons of bombs, and continued the war for almost a decade. Three million Vietnamese people lost their lives and more than 58,000 Americans.

Many of these lives were sacrificed to maintain an image of unyielding U.S. power. Seven U.S. presidents, over eleven terms, deemed the human consequences of war irrelevant. Seven presidents considered withdrawal from Vietnam and Afghanistan an intolerable admission of personal, political, and national weakness. They extinguished millions of lives to preserve American “credibility,” a term used by policymakers not as a synonym for honesty or trustworthiness (as in common usage), but as a signifier of the nation’s unrelenting will to use military power. Ironically, of course, the longer the United States prolonged its wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan, the more actual credibility it lost in many spaces around the world and at home. This commitment to perpetuating U.S. imperialism at any cost demands a fuller explanation than maintaining “credibility.”

Since World War II, every U.S. president has pledged to maintain, and even expand, U.S. global military dominance. The consistent underlying justification is American exceptionalism—the dangerous myth that the United States is an invincible and indispensable force for good in the world. Though reality has repeatedly disproved that faith, it still permeates the centers of national power and much of our culture and media. The convenient thing about faith is that evidence is not needed to maintain it.

That said, people do sometimes lose faith. After all, polls show that before the late 1960s a great majority of the public trusted the federal government. Since then that trust can be found in only about one-third of people. Yet, even so, many people maintain faith in American exceptionalism and defer to the executive branch and the military industrial complex, assuming that ordinary people cannot wrest control of foreign policy from the tiny elite that has controlled it for so long.

Significantly, although broad faith in American exceptionalism persists, it coexists with substantial antiwar public opinion. Throughout U.S. history, the public has often been more dovish than its leaders, but only rarely—as in the 1960s—has antiwar sentiment coalesced into a massive, sustained, and diverse movement. Lacking powerful opposition, the foreign policy establishment realizes it can continue to insist on “full spectrum dominance” of the planet and wage war anywhere without public consent or a congressional declaration.

President Biden’s decision to leave Afghanistan thus marks a significant break from this tradition. No other president has had the courage to pull the plug so decisively. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that he is also prepared to begin a substantial draw down of the U.S. imperial footprint or dramatically demilitarize foreign policy. In fact, he has already vowed to continue drone strikes in Afghanistan and elsewhere even as evidence continues to mount that these “targeted” assassinations very often produce civilian casualties (further complicating the dubious morality of “successful” drone strikes). In the most recent example, U.S. commanders have now conceded that the August 29 “retaliatory” drone strike in the wake of the suicide bombing near the Kabul Airport did not kill members of Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), but ten civilians, seven of them children. And while U.S. forces may be out of Afghanistan, they continue to operate in scores of other countries while the administration and the Senate call for yet another increase in military spending.

To justify the war today, the prominent “if only” finds basis in the idea that the United States lost its “focus” on Afghanistan in 2003 when it invaded Iraq. If only we hadn’t been distracted by this additional and more controversial war, we might have prevailed. This critique is hardly new. Indeed, Barack Obama anticipated it by more than a decade. When he ran for president in 2008, he proclaimed Afghanistan a “necessary” war that had been side-tracked by the bad war in Iraq. During his first year in office, President Obama initiated more than tripling the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan, from 30,000 when he entered office and to 100,000 by 2011. When the “surge” failed, he reversed direction and lowered the number of troops. By 2014 he claimed that enemy forces had been sufficiently degraded to announce an end to combat missions. That proved as premature and fatuous as Bush’s similar claim in 2003 about Iraq, famously made on an aircraft carrier in front of a gigantic sign reading “Mission Accomplished.”

When Obama went to West Point in 2009 to announce his major escalation of the war, he insisted that he was not embarking on a nation-building project without end. “The days of providing a blank check are over.” As Craig Whitlock matter-of-factly points out, “the United States would keep signing one blank check after another.” The cost of the Afghanistan War is an estimated $2.3 trillion.

A few “if only” scenarios are worthy of serious consideration. When the U.S. began attacking al-Qaeda targets in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, the Bush administration was not clear about its goal for the Taliban government. They believed that it should be punished—but should it be overthrown? If so, should the United States take responsibility for replacing it? And what about further nation-building efforts? In an ad hoc way, the Bush administration lurched from the smallest goals to the largest, a classic example of mission creep. Part of what inspired them was the unexpected speed of the Taliban collapse, occurring just a month after the war began.

President Bush had other options, now mostly forgotten. Just a few days into the initial bombing, the Taliban offered to turn over Osama bin Laden to a third country if the United States stopped the bombing and provided evidence of bin Laden’s responsibility for the 9/11 attacks. Bush categorically refused the proposal. Then, in November 2001, the Taliban offered to give up its arms and surrender in return for amnesty. If we had accepted, the war might have ended or taken a less lethal path forward. Yet, Bush again rejected the Taliban offer. When asked about it at a news conference, Rumsfeld said simply, “the United States is not inclined to negotiate surrenders.” Nor was even a glimmer of thought given to inviting Taliban representatives to participate in a conference in Bonn in December 2001, where the United States convened a meeting of Afghan power brokers to discuss a power sharing agreement.

Of course, no one knows what might have happened had U.S. leaders taken those options. Nearly twenty years later, in 2020, President Donald Trump did negotiate with the Taliban, though they had not offered to disarm and surrender. To the contrary, they were more powerful than at any time since 9/11. Trump offered to take out all U.S. troops if they promised not to shoot them while they withdrew. As New York Times journalist Alissa J. Rubin recently put it: “For some veterans of America’s entanglement in Afghanistan, it is hard to imagine that talks with the Taliban in 2001 would have yielded a worse outcome than what the United States ultimately got.”

The “worse outcome” included not just a defeat that returned the Taliban to power, but a twenty-year war in which the United States wreaked untold levels of suffering and terror. It began immediately with the massive cash payouts to the warlords of the “Northern Alliance,” some of whom assumed senior posts in the U.S.-backed Afghan government. According to Human Rights Watch, they included some of the top war criminals in the country. One of them, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, shelled and looted Kabul in the early ’90s after having fought for the Communist government during the Soviet-Afghan war. In November 2001 Dostum suffocated to death hundreds of Taliban prisoners (up to 2,000 by some estimates) by packing them into sealed shipping containers and waiting for them to die. Neither the Bush nor Obama administrations investigated that war crime despite incontrovertible evidence.

The Afghanistan Papers provides insider confirmation that “the Americans made the warlords a permanent fixture” of the post-Taliban government. That alone guaranteed that the United States would continue support to a profoundly corrupt state. The corruption was fueled by mass infusions of U.S. money and the vast expansion of opium production. Moreover, U.S.-backed warlords and officials were among the biggest drug traffickers. By the end of the U.S. occupation, Afghanistan was producing 80 to 90 percent of the world’s opium. As James Risen puts it, “For twenty years, America essentially ran a narco-state in Afghanistan.” Throughout it all, U.S. officials and officers went before Congress and the public to assert, with straight faces, that the United States had “momentum” in Afghanistan and was making “steady progress.” Or, as the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, said in 2013, “the conditions are set for winning this war.”

Though Whitlock’s The Afghanistan Papers is a powerful indictment of the war, it would have offered an even stronger one had it included more evidence of the brutality endemic to the Global War on Terror. The lies each administration told about the war deflected attention not only from failed policies, but torture at dark sites in Afghanistan, extraordinary rendition (kidnapping of terror suspects), routine night raids to kill or capture suspects (bringing terror and sometimes death to many thousands of civilians), and ever more reliance on bombing and drone warfare.

This is not an omission unique to Whitlock’s book. Indeed, a moral critique of the Global War on Terror never gained the coherence and passion that characterized the Vietnam War. For example, by 1971 a poll found that 71 percent of Americans believed that the war was a mistake, and 58 percent also believed it immoral. During the twenty-first-century wars, only periodic attention has focused on evidence of U.S. war crimes, racism, and torture. In part this reflects the fact that the War in Vietnam was far more deadly, but there is also more to the story.

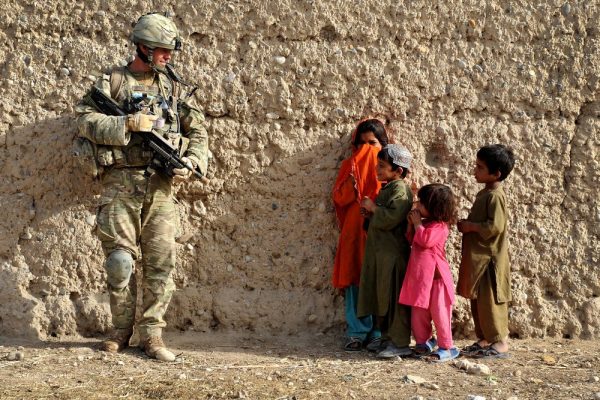

While U.S. media coverage in Vietnam was constant and unavoidable, it was not in Afghanistan. When war crimes surfaced, the stories quickly faded. Many of them were discovered not by journalists but by troops themselves—some of whom seemed delighted to document them with their cell phones and others who were moved by conscience, like whistleblowers Chelsea Manning and Daniel Hale. In 2012, for example, a video appeared showing four U.S. Marines laughing as they urinated on Afghan corpses. Two months later a U.S. soldier went into two Kandahar villages in the early morning and murdered sixteen civilians, most of them women and children. A month later photos of soldiers from the 82 Airborne Division were leaked to the LA Times. The photos, taken in 2010, depict them posing as they hold up the severed legs of a suicide bomber. In response, U.S. leaders all echoed Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta: “This is not who we are, and it’s certainly not who we represent.”

This response exemplifies yet another strain of American exceptionalism—endemic violence and wrongful aggression characterizes our enemies alone; it is not who we are. And thus, it was no surprise in the final weeks of the war that coverage did not examine the long, ugly history that led to this outcome, but instead focused on the desperate crowds seeking escape and questioned why the United States was “abandoning” them.

In these final hour displays of concern for the plight of Afghans, especially women, little consideration went to the twenty years of failed U.S. policy (forty years if we go back to the U.S. role in the Afghan-Soviet war). Nor do the gains of some Afghans offset the suffering of the many (a minority of people always prosper under foreign occupation). It is true that roughly one-third of Afghan girls were receiving primary and secondary education by 2017, and one-fifth of civil servants were women (under the Taliban those opportunities were forbidden). But those tenuous gains are hardly threatened by the Taliban alone. Many U.S.-backed warlords were every bit as brutality repressive of women’s rights. Nor are most Afghan men in favor of gender equality. A recent UN study found that only 15 percent of Afghan men believe women should be allowed to work outside their home after marriage.

Now, the plight of refugees foregrounded in the media warrants not just concern, but support. Here is an occasion to reflect on the great number of refugees for which the United States has been responsible. While the searing images of war’s end in Afghanistan, as in Vietnam, will be indelibly remembered by many, who will remember the millions of people displaced from their homes during the long years before the end? During the Vietnam War, the United States intentionally drove millions of Vietnamese civilians out of their rural hamlets and put them in “strategic hamlets,” or refugee camps, or left them to fend for themselves in the swelling cities and shantytowns outside U.S. bases. In Afghanistan American war again led to massive dislocations: some 5 million Afghans became wartime refugees. We abandoned them long before the war was over.