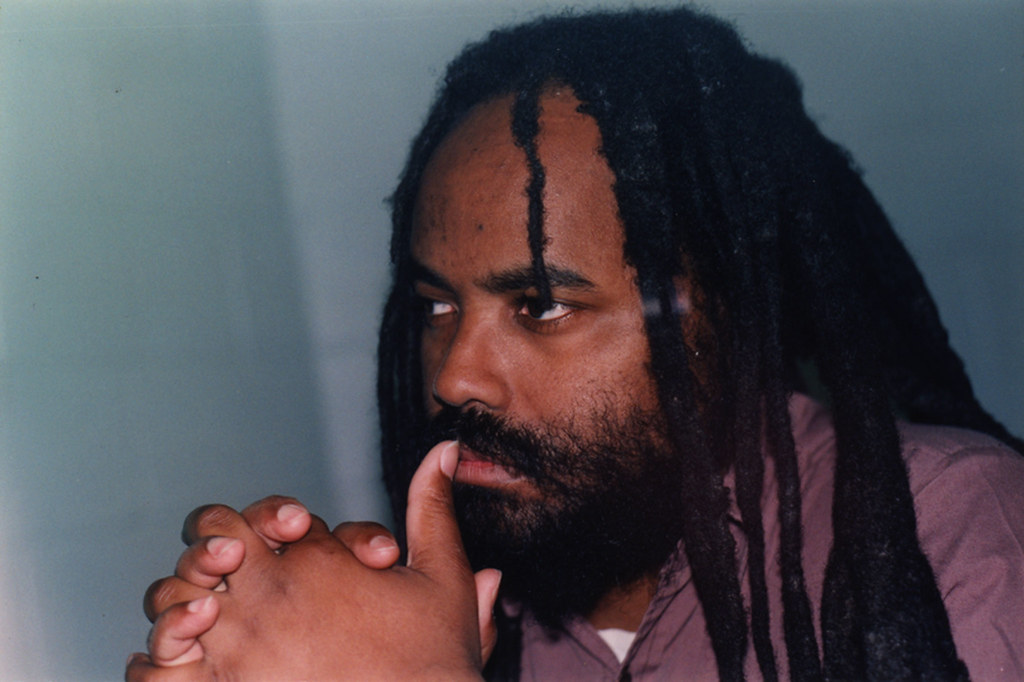

Unless he is saved in the coming weeks and months by an international campaign of protest, or by an unlikely Supreme Court decision in his favor, black activist Mumia Abu- Jamal will be executed soon by the state of Pennsylvania for allegedly shooting a Philadelphia police officer in 1981. Convicted in a farcical 1982 trial presided by the notorious "hanging judge" Albert Sabo (responsible for handing down more death penalties than any judge in the United States), Abu-Jamal was saved from execution in 1995 after a wave of international protest. Judge Sabo presided again at the hearing for a retrial, and not surprisingly ruled against Abu-Jamal. This fall, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld Sabo's decision, and newly re-elected Governor Tom Ridge campaigned on a promise to sign Abu-Jamal's death warrant. The Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police vigorously campaigned both for Ridge's re-election and for the election of five of the seven state Supreme Court judges who voted against a retrial.

The international protest that won Abu-Jamal a reprieve three years ago included interventions of such heads of state as Nelson Mandela and Jacques Chirac. This case has every chance of achieving the world notoriety of previous American political trials, from Tom Mooney, by way of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Scottsboro boys, and the Rosenbergs, to Huey Newton and Angela Davis. On the level of popular outrage, the execution of Abu-Jamal could bring black Philadelphia into the streets in a way not seen since the 1960s.

Moreover, coming within months of the first Amnesty International report on human rights abuses in the United States,1 the denouement of Abu-Jamal's case will also cast a bright light on American prisons, police brutality, and the accelerating, racist use of the death penalty in this country. In 1997, only China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia officially executed more people than the United States. From 1989 to 1994, the United States, the world model of liberal democratic capitalism, rivaled Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, apartheid-era South Africa, the Soviet Union, and Yemen in the frequency of its executions.2 With 1.8 million people currently behind bars, the United States also has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world: nearly one percent of the population is either in jail, awaiting trial, or on parole and probation.

In the 1960s, the Philadelphia police, guided by law-and-order Frank Rizzo, earned a reputation for brutality against blacks. The pattern continued through subsequent decades. In 1979, the US Department of Justice filed a civil rights lawsuit against the Philadelphia police for systematic intimidation of witnesses and tampering with evidence, themes that would recur in Abu-Jamal's trial and in the controversy it generated. In 1985, then-mayor Wilson Goode, a black Democrat, authorized the police helicopter bombing of the house of MOVE, a black nationalist group. In the ensuing fire, 11 MOVE members, including five children, were killed, and 61 houses in the vicinity burned to the ground. In 1995, federal investigations uncovered systematic witness intimidation and falsification of evidence against black and Latino defendants in the city's 39th Police District. In the aftermath, 300 convictions were overturned, and many wrongly accused persons released from prison.

Mumia Abu-Jamal first attracted police attention as a teenage member of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s. After the Party's demise in the early 1970s, Abu-Jamal remained an activist and radical journalist. On December 9, 1981, during his night shift as a cab driver, Abu-Jamal came across a Philadelphia police officer, Daniel Faulkner, who he claimed was beating his brother, Billy Cook. In the ensuing altercation shots were fired; Abu-Jamal was seriously wounded and Faulkner was killed. Five witnesses at the scene have stated that they saw another black man shoot Faulkner and flee.3 One of them, William Singletary, was a decorated Vietnam vet and Philadelphia businessman. He was held for hours by Philadelphia police, who repeatedly tore up his accounts of seeing another man shoot Faulkner. After finally relenting and signing a statement that he did not see the shooting, Singletary was forced to abandon his Philadelphia business by constant police harassment, threats, and suspicious damage to his gas station. He left Philadelphia and was only located by Abu-Jamal's lawyers many years later.

Of the five witnesses who claim to have seen someone else shoot Faulkner, only a black accounting student stuck to his story while testifying at the 1982 trial, during which the prosecution falsely told the court that he had failed a polygraph test. Under pressure from Philadelphia police, Singletary and three others all changed or retracted their testimony. Meanwhile, the key prosecution witness against Jamal, a prostitute named Cynthia White (whom no other witness saw at the scene), was allowed by police to ply her trade unhindered for years thereafter and was released without bail on felony charges in 1987 at the recommendation of a Philadelphia police detective. She has disappeared and the Philadelphia police claim she is dead.4

In the original trial, the prosecution also claimed that Abu-Jamal had confessed on the night of the shooting, while under police surveillance in a hospital. The existence of this confession was only revealed two months after the shooting, and contradicts the report filed that night by the Philadelphia officer guarding Abu-Jamal, which said that "the negro male had made no comments." When asked to explain this contradiction, the policeman said he had not realized the importance of Abu- Jamal's hospital confession at the time, and had not mentioned it in his report. Indications of tampering with evidence have also emerged in the prosecution's case.

The 1995 hearing for a retrial followed the same patterns. Judge Sabo denied the defense any discovery, quashed 25 defense subpoenas, and ruled out the presentation of new evidence by the defense. He fined Abu-Jamal's attorney Leonard Weinglass $1,000 and jailed attorney Rachel Wolkenstein for objecting to the quashing of evidence of racial bias in the use of the death penalty in Philadelphia."5 When in 1996 Veronica Jones, a prostitute who had testified against Abu-Jamal in 1982, came forward to reverse her earlier statements and testify in Abu-Jamal's favor at a hearing, she was arrested on the witness stand on a two-year-old bench warrant issued in New Jersey. Sabo's bias against the defense was so obvious that the normally pro-police Philadelphia Daily News wrote on October 2, 1996 that his "heavy-handed tactics can only confirm suspicions that the court is incapable of giving Abu-Jamal a fair-hearing."

While defense attorneys were facing large hurdles, the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) intervened in the case unhindered. Members have packed the court room for every hearing, staged street demonstrations, and taken out ads in the New York Times calling for the quick execution of the "cop killer." When the Philadelphia hospital workers local 1199C rented its union hall for a event to benefit Abu-Jamal's defense, the union was besieged by 300 Philadelphia policemen.

Pennsylvania labor unions, on the local level, have come down on both sides of the case. Prison guards at the state penitentiary where Abu-Jamal is being held are organized in AFSCME, and have pressed the labor movement for sympathy. Yet in March 1998, the guards swept through the cells of death row inmates, confiscating all manner of personal property, including Abu-Jamal's personal library, which he used for journalism about prison conditions. Inmates responded with two hunger strikes, and when a video recorded violence by guards against some of them, several guards were fired. They have attempted to enlist the union and the rest of the labor movement in their campaign for reinstatement. UMW and USW locals in the vicinity of the prison have made public statements on behalf of the fired guards, whereas the UE and the SEIU have come out in support of Abu-Jamal. At its convention in Pittsburgh in November, the Labor Party also came out against the impending execution.

In 1995, Pennsylvania authorities were stunned by the depth of national and international protest set in motion by the case. An even larger protest will be necessary now to get their attention.6 Abu-Jamal has one appeal left, to the US Supreme Court. But the "anti-terrorist" law passed in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing has significantly narrowed the scope of the appeal. Only the possibility of serious damage to the United States' image abroad seems sufficient to get the attention of politicians. The Abu-Jamal case presents an excellent opportunity to turn the spotlight of international outrage on the conditions allowed to fester in the country that presents itself to the world as the model of democracy-and on the police, state prosecutors, media, and prison system whose methods have been sketched above.

Notes

1United States of America: Rights for All (Amnesty International, 322 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10001).

2Roger Hood, The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 74.

3The following facts about Abu-Jamal's arrest, trial, and appeal are taken from the publications of the Partisan Defense Committee, one of the groups which has been working for his release. PDC publications are available from PO Box 99, Canal Street Station, New York NY 10013-0099. Further information is available from the International Friends and Family of Mumia Abu-Jamal, PO Box 19709, Philadelphia PA 19143.

4White was also identified as a police informant by a government witness in the 1995 investigation of the 39th District of the Philadelphia police.

5According to the Amnesty International report cited above, one study done in Philadelphia showed that being black increased four times the likelihood of a death sentence. United States of America: Rights for All, p. 109.

6A massive demonstration is currently scheduled for April 24 in Philadelphia. Contact (781) 391-4093 or cedpboston@yahoo.com for more information. To express views on the Abu-Jamal case to the Pennsylvania authorities, write to Governor Tom Ridge at Main Capitol Building #225, Harrisburg, PA 17120, or email governor@state.pa.us.