In coming weeks, the Northeast of the United States will experience the peak of its annual migration of monarch butterflies. The butterflies’ life cycle takes place over an astonishingly broad geographic range. Each year, the monarchs overwinter by the millions in the high-altitude forests of Mexico. Then, in the spring and summer, they head north to the United States and southern Canada, the northern limit of where milkweed, the only plants that the fastidious monarchs breed on, will grow.

Gómez González had long known that his life was on the line. In a showdown between organized crime and organized butterfly protection, there was only likely to be one winner.

Because so many ecological factors have to sync perfectly for this journey to work, in recent decades the monarch population has declined rapidly under pressure of environmental changes. In response, a grassroots network of butterfly defenders has sought to preserve the multiple environments that the butterflies need. In the process, the defenders—and, by extension, the butterflies—have made surprising enemies.

On January 29, 2020, Homero Gómez González, who managed Mexico’s El Rosario Monarch Butterfly Preserve, was found floating in a reservoir with his head bashed in. Then on February 1, a second butterfly protector, Raúl Hernández Romero, was found stabbed to death on a hilltop not far away. Both murders occurred in the Mexican state of Michoacán, directly west of Mexico City. Michoacán is home to the world’s largest monarch roosts, but it is also a hotspot for violence stemming from organized crime.

Meanwhile, 700 miles north, Mariana Treviño-Wright, executive director of the National Butterfly Center in Mission, Texas, has endured months of escalating rape and death threats in response to her butterfly conservation work along the Rio Grande. The center is an ecological mecca and home to 240 species of butterflies, a third of the total found within the United States. Treviño-Wright had imagined that butterfly protection might fall outside U.S. political polarities. But the sanctuary has the misfortune of abutting the politically tumultuous Rio Grande in the age of Trump.

As a result, Treviño-Wright, to her terror and astonishment, has found herself in the crosshairs of white nationalists hellbent on erecting a border wall. Leading the attacks against her is Brian Kolfage, a triple-amputee war veteran and founder of We Build the Wall, Inc. The group arose out of a frustration that obstructionist “left-wing politicians” were thwarting Trump’s wall project. So Kolfage and his followers decided to go freelance. In December 2018, they launched a GoFundMe campaign that has $25.5 million pledged from a quarter million donors. When it became clear to them that it was not legally possible to donate the funds toward the government’s border wall, they committed to using the funds to privately build a wall along the southern border. After erecting short, unauthorized sections of wall on private land in Florida and New Mexico, the group set up shop building several miles of wall on private land in Mission, directly on the banks of the Rio Grande and nearly abutting the National Butterfly Center. In December 2019, the North American Butterfly Center obtained a temporary restraining order halting We Build the Wall’s construction on environmental grounds, which has only worsened the hatred directed at Treviño-Wright. Even before the injunction, Kolfage had traduced the sanctuary on Twitter as a den of butterfly smuggling and a front for “rampant sex trade.”

By the time of the restraining order, though, Build the Wall’s three-and-a-half-mile “border” wall in Mission was well under way, and the National Butterfly Center estimates that for every mile of barrier, twenty acres of habitat are obliterated. The sanctuary’s ecological value exceeds the life within its boundaries, for it serves as a vital natural corridor, not least for monarchs on the move. The towering wall and razed habitat threaten far more than human and butterfly migrants. If the Rio Grande floods—as it did in 2018 when the river rose sixteen feet overnight—fleeing wildlife such as bobcat, coatimundis, and peccaries will literally hit a wall and drown en masse.

The towering wall threatens far more than human and butterfly migrants. If the Rio Grande floods—as it did in 2018 when the river rose sixteen feet overnight—fleeing wildlife such as bobcat, coatimundis, and peccaries will literally hit a wall and drown en masse.

Treviño-Wright’s beleaguered sanctuary serves as a way station for southbound butterflies, but once they cross the border, they fly into a different storm of troubles. They’re heading for the forests of Michoacán, 10,000 feet above sea level, where millions of monarchs huddle in a state of semi-hibernation. The oyamel firs offer the fickle insects a microclimate precisely suited to their needs. So thickly do they coat the trees that a 100-foot oyamel trunk can seem enveloped in orange bark. Half-gram monarchs, massed for warmth, can bend and buckle sturdy boughs.

Michoacán’s El Rosario reserve attracts millions of monarchs annually and tens of thousands of butterfly tourists. But the reserve has also proven attractive to illegal loggers, who covet the fir trees and the land beneath. The butterflies, oblivious to human inequality, travel between the wealth of the United States and the destitution of one of Mexico’s poorest states; Michoacán’s GDP is about $4,700. As one anonymous Mexican conservationist observed, “Around here a tree is worth more than a human life.”

Until his assassination in January, Gómez González managed the El Rosario reserve. Gómez González was a logger from a long lineage of loggers. Initially, he viewed the butterfly-induced protection of the forests as an affront to indigent locals seeking to survive. But slowly his politics turned and—with World Wildlife Fund patronage–—he became a vocal advocate for monarch-driven ecotourism as an alternative path out of poverty. He led a reforestation program. He launched patrols day and night on the lookout for illegal incursions. And he took to social media with videos of himself haloed with hovering monarchs. After two years of his charismatic leadership, the rate of deforestation fell to almost zero. But he was accumulating enemies, among them not only loggers but those wishing to plant clandestine avocado orchards, a lucrative crop thanks to soaring U.S. demand.

Gómez González was last seen alive on January 13 at a local fair. When the ransom notes arrived, his family paid. It took two weeks to find his corpse. The autopsy determined the cause of death as “mechanical asphyxiation by drowning of a person with head trauma.” Gómez González had long known that his life was on the line. In a showdown between organized crime and organized butterfly protection, there was only likely to be one winner.

A day after Gómez González disappeared, Hernández Romero vanished as well. He was last seen en route to work in a village called El Oyamel, named after the conifers he adored, the Abies religiosa, or sacred firs in English. The pilgrim butterflies prize them but so do human pilgrims: Mexican loggers fell large numbers of the sacred firs to adorn churches each Christmas.

Hernández Romero had denounced illegal logging before he was tortured and knifed to death. He worked as an ecotourist guide in a section of the vast Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve that UNESCO declared a world heritage site in 2008. Hernández Romero put his body on the line trying to reconcile his passion for the monarchs’ splendor with local skepticism that ecotourism could fill the stomachs of the poor. He believed, despite the odds, that such a reconciliation was possible.

Those who wish to protest the assassination of the butterfly guardians face a dilemma. How can we honor Gómez González and Hernández Romero by denouncing a culture of murderous impunity without scaring off ecotourists who offer a lifeline to the monarchs, the oyamel firs, and locals?

UNESCO has extolled the monarch migration as “a superlative natural phenomenon.” But what pathways are open for conserving a superlative natural phenomenon amidst desperate people scrambling to survive? Gómez González and Hernández Romero believed an avenue forward could be found, so long as they could keep the illegal loggers and avocado mafia at bay, while persuading the butterfly tourists to keep coming.

But will they? Mexico’s soaring violence could drive visitors away. Ecotourism is at best a precarious experiment in Michoacán’s fragile forests. If the monarchs are to survive, the margin for forest decline is minute. So those who wish to protest the assassination of the butterfly guardians face a dilemma. How can we honor Gómez González and Hernández Romero by denouncing a culture of murderous impunity without scaring off ecotourists who offer a lifeline to the monarchs, the oyamel firs, and locals?

If ecotourism faces an unsteady future, so do the monarchs. They are beset by hazards at both ends of their journey and all stops in between. The Holocene’s relatively stable life-support systems have given way to an unsettled Anthropocene that pressures species to evolve rapidly to cope with accelerating ecosystem change. Some generalists—crows, raccoons, urbanizing foxes, and landfill-loving gulls—are flourishing. But monarchs are not well placed. Like koalas, with their fickle diet of eucalyptus leaves, monarchs are a niche species ill suited to turbulent times.

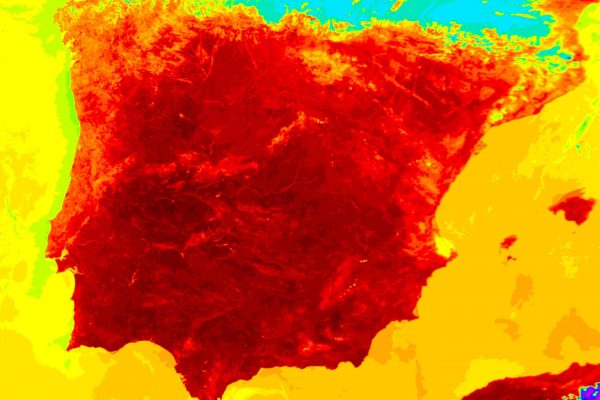

Monarchs’ survival depends on two groups of plants—the oyamel firs down south and milkweed up north—that anchor their life cycle. Climate disruption is stressing the Michoacán firs at one end of the journey and milkweed at the other. Monarchs and milkweed didn’t coevolve in fields doused with Roundup. And too often the grassy verges of North American highways and parks where milkweed flourishes get mown to smithereens, interrupting the monarchs’ breeding cycle. Moreover, monarchs head south during early fall, the apex of hurricane season. As the oceans warm, hurricanes are growing more severe, further jeopardizing these delicate travelers. In short, the 2-million-year-old arc of migrant monarch life depends on rhythms ill matched to an increasingly arrhythmic world.

Experiencing nature in the aggregate can have enormous power, even when that plenitude is illusory. Defaunation—the diminishing numbers of living creatures—receives less attention than extinction but is arguably as perturbing. Defaunation shrinks the possibilities for those natural encounters that, for so many of us, enliven our time on Earth. In an era when nature’s ranks are thinning, the spectacle of a Mexican forest bending beneath thronging monarchs affords a brief, sustaining fantasy that life can and will continue as it was.

It can’t and won’t. The North American monarch population has plummeted from 1 billion to 93 million over the past two decades. While 93 million is a long way from extinction, the butterfly’s decline is unsustainably precipitous. We are on course to lose not just a species but a great pattern of being that offers a distinctive kind of amazement and joy. Like the vast herds of wildebeest slogging across the savannah, like the caribou trekking through the Arctic, the monarch multitudes bind together far-flung places—a Michoacán fir forest and a patch of milkweed in suburban New Jersey—that might otherwise seem worlds apart. The monarchs find belonging in bold movement.

The monarch population has plummeted from 1 billion to 93 million over the past two decades. While 93 million is a long way from extinction, the butterfly’s decline is unsustainably precipitous. We are on course to lose not just a species but a great pattern of being that offers a distinctive kind of amazement and joy.

Monarchs’ transnational journey is a kind of papier-mâché madness. Each individual looks so ill equipped to travel 2,800 miles from Mexico to Ontario. If the migratory pattern itself is at risk, the individual migrants—the breeze-buffeted butterflies—look like they should not even contemplate leaving home, let alone undertake a biannual odyssey.

No individual monarch among the migrant millions will ever complete the round trip. Most monarchs live for just a month or two. Unlike wildebeest and caribou, the butterflies that depart each autumn are never the ones that return. Monarch migration is a relay race rather than an individual marathon, as the dying pass the baton to those just emerging. Together, the expiring and the aspiring constitute a long ribbon of life that links egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly across different phases of the journey.

The monarchs ordinarily arrive in Michoacán as October gives way to November, arriving just in time for Día de Muertos. For many Mexicans, the butterflies assume a profound significance, not just as a seasonal marker, but as a physical manifestation of the fluttering souls of the deceased, who depart but remember to return each year to visit those they love.

This past winter, the winter of the Mexican butterfly martyrs, was the best year for migrating monarchs since 2006–7, as it had been anecdotally that summer for gardeners through the Northeast. But it seems that the bumper year was a fluke, not a trend toward recovery. Canadian monarch expert Ryan Norris called it “a Goldilocks year, not too hot, not too cold, it was perfect.” For the monarch, the overall drift is downward, as climate breakdown intensifies along with other human hazards. Lepidopterists predict that, at current rates, in thirty years the great migration may be history. Mexican poet and environmental activist, Homero Aridjis, anticipates that moment of the monarchs’ ultimate vanishing: “All have gone, only I stay on / chasing the shadows of butterflies under the full moon.”

In our garden in Princeton, New Jersey, my wife, Anne, and I planted milkweed this spring, as we have done for the past two years. We assiduously check the progress of the lurid green-, white-, and black-striped caterpillars that, having hatched on the plants in spring, eat nothing but those leaves. In October we will watch a bright new batch of monarchs turn south with the turning of the year. When they’re gone, we’ll hack back the unsightly, ragged milkweed stems.

One milkweed at a time, Anne and I are trying to shield the monarchs, to shelter what remains. But at the far end of the butterflies’ journey, amidst the oyamel firs, who will be there to defend the butterfly defenders?

Beside me, as I write this, lies a copy of nonprofit environmental watchdog Global Witness’s July 2020 annual report, “Defending Tomorrow.” The report chronicles the persecution and assassination of environmental defenders worldwide during the last calendar year. In 2019, yet again, Mexico ranks as one of the most dangerous societies in which to take a stand for environmental and human rights. This time next year, when I receive Global Witness’s 2020 report, I will open it and find the names of two butterfly martyrs, Homero Gómez González and Raúl Hernández Romeo, swelling the global tally.

Luckily Treviño-Wright continues to oversee the National Butterfly Sanctuary, traumatized but still advocating for butterflies and the ecosystems they rely on. For now, bright wisps of life continue to flutter across the borders of a sorely divided continent. For now, an ancient pattern of being stretching back to the Pleistocene continues, carried forward by a brief multitude of fragile wings. For now, for now, the pattern persists.