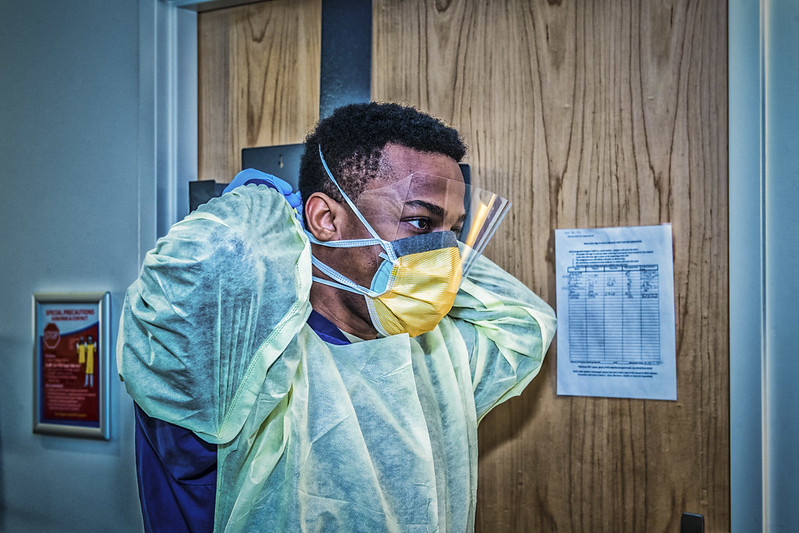

At the peak of the pandemic in Connecticut, I was walking to my car after a shift in the emergency room, and I couldn’t shake one of my patients from my thoughts. He was a father who’d been having trouble breathing. I’d seen enough patients like him to know that he had COVID-19. Through several layers of personal protective equipment (PPE) muffling my voice, I told him that I would have to intubate him and connect him to a breathing machine to save his life. Tears in his eyes, he pleaded with me not to do it. “Dr. Chandler,” he said, “I’m scared.” He was worried about his critically ill children, who were already in our intensive care unit with COVID-19, and his wife who was sick at home with the virus.

As I left the hospital in an emotional haze, I was shocked by the sight of unmasked demonstrators protesting social distancing. I dodged signs that said “#fakecrisis” and “#hoax.” It reminded me of the news stories about public health officials across the country receiving death threats and being forced to resign over concerns about their personal safety. Already exhausted from the shift, I was devastated. These protesters were demanding the right not to wear masks when my colleagues and I had been warned by our hospital that we could run out of PPE within two weeks. The protest demonstrated callous disregard for this family’s tragedy; it felt like a slap in the face to the work I do every day as an emergency medicine doctor.

COVID-19 should be a reality check for physicians. It shatters any illusion that doctors do not function as labor-for-profit in the current health care system.

I reflected on this incident with my colleagues Marco Ramos and Tess Lanzarotta, one a psychiatrist and both historians of medicine. We came to feel it crystallized the way COVID-19 has exposed the deep rifts, fissures, and inequities that undergird health care under racial capitalism in the United States. We have seen that our society is willing to exploit frontline medical workers and force them to work in unsafe environments, without access to PPE. There has been no real, coordinated national public health response. And the pandemic has once again exposed deep-seated racial health disparities that mean Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities will suffer disproportionately. Black men and women, especially, are being hit twice: both by a novel virus and by systemic police brutality and racism. As activist Rajikh Hayes recently stated, “Am I going to let a disease kill me or am I going to let the system—the police?”

The response of the largest professional organization of physicians, the American Medical Association (AMA), has been woefully inadequate in the face of this national crisis. Its efforts have focused on lobbying an administration that has consistently downplayed issues of workplace safety and called the deaths of health care workers a “beautiful” act of sacrifice, “just like soldiers run into bullets.” This stands in sharp contrast to National Nurses United (NNU), which has aggressively advocated for workplace protections amid this pandemic—filing over 125 complaints with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 16 states to protect its workers from unsafe environments. On International Workers Day the union supported nationwide protests of nurses at 139 hospitals across 13 states to demand adequate safety protections. The union’s membership, already 150,000 today, is climbing. Interest in doctors’ unions has grown, too, particularly among young physicians-in-training during this pandemic, but as it stands unions have failed to catch on industry-wide.

The AMA’s response to structural racism and the Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality, meanwhile, have been little more than lip service. Along with some academic medical centers, the organization has put forward vague statements mourning the death of George Floyd and supporting “opposition to racism.” Whereas groups like White Coats for Black Lives, mostly led by young physicians of color, have demanded concrete steps to address systemic racism in health care, the premier physicians’ organization in the country has issued only empty platitudes without any intention of enacting structural change. This is not a coincidence. Even as the diversity of the medical profession has increased, the AMA has remained overwhelmingly white. Many doctors and patients alike see the AMA as ineffective and out of touch. Indeed, the AMA’s membership has declined steadily since its heyday in the 1950s, when it represented three-quarters of all physicians. Today, it represents just a quarter.

A long history of medical elitism prevents doctors from identifying as workers who can collectively organize for their rights and as advocates who can stand in solidarity with movements for social justice.

Why have doctors had such difficulty advocating for themselves and their patients, even when lives are at stake? There are roughly a million physicians in the United States today. But where is their collective voice? And why is it important—for physicians and society as a whole—that doctors find their political footing to combat both this novel virus and the systemic racism threatening communities of color?

The answers lie in the distinctive history of medical labor under U.S. capitalism. Throughout the twentieth century physicians in the AMA cultivated an understanding of medicine as an “elite profession”—generally coded as white, affluent, and male. This racist, sexist, and classist image of the “good doctor” continues to impede physicians’ ability to effectively advocate for themselves and their patients today. Medical elitism prevents doctors from identifying as workers who can collectively organize for their rights or as advocates who can stand in solidarity with movements for social justice.

The conditions of physicians’ labor have changed dramatically over the last century, but the political consciousness of doctors has not. The current crisis is an opportunity for physicians to shed the elitism of their profession’s past and form a new vision of the American doctor based on the pursuit of justice and provision of healing.

• • •

White Supremacy and the AMA in Medicine’s “Golden Age”

For over a century the AMA has been the largest and most powerful physicians’ group in the United States. It lobbies legislators and pursues legal actions that promote its vision of a powerful, united medical profession. But this was not always the case. In the mid-nineteenth century American medicine was a heterogeneous field with various sects of practitioners vying for prominence. Fierce competition, a lack of regulation, and dubious treatments meant that the business of healing lacked the prestige it enjoys today. Medicine, as a whole, occupied what historians have called a “demoralized position” in American society.

In the absence of regulation, nineteenth-century medicine was surprisingly diverse in terms of both healers’ practices and their identities. The first Black medical college, at Howard University, opened its doors in 1868, and there were eight Black medical colleges by the turn of the century. The first woman, Elizabeth Blackwell, graduated from Geneva Medical College in 1849 and the first Black woman, Rebecca Lee Crumpler, graduated from New England Female Medical College in 1864. Without a doubt, these physicians faced structural obstacles that many of their white male colleagues did not, including racism, sexism, and lack of access to advanced medical technologies and educational opportunities. But overall, the number of Black and women doctors grew in the second half of the nineteenth century.

COVID-19 has exposed the deep rifts, fissures, and inequities that undergird health care under racial capitalism in the United States.

This would all change at the turn of the century with the rising power of the AMA, an organization that displayed a staggering commitment to racism and segregation. Founded in 1847, the group started out as one among many fledgling professional associations struggling for legitimacy in the competitive medical marketplace of the nineteenth century. The AMA’s creators were young, white men who wanted to rebrand the “low status” of the American doctor and transform medicine into an elite, prestigious, and respectable profession. The organization admitted a small number of white women in the nineteenth century, although this decision aroused some controversy. Black doctors were not afforded the same privilege—the AMA refused to admit Black delegates at the national level and tacitly approved of segregation in local and state medical societies. Even at the time, such policies were criticized as racist in national medical journals.

The AMA’s vision of the prototypical doctor was someone who looked like its members: a well-educated and well-off white man who practiced medicine according to scientific principles. In 1910 the group developed an influential tool for standardizing American medicine in that image: the Flexner Report, an “audit” of medical schools that was designed to make medical education more rigorous and scientific. The education reformer Abraham Flexner traveled to 155 schools and recommended the closure of those that did not meet his standards. Many state medical boards quickly took up his suggestions. After all, as Kenneth M. Ludmerer points out in Learning to Heal: The Development of American Medical Education (1988), the AMA’s “judgments” had come to “have the force of law.”

Within two years of the Flexner Report’s publication, three of the seven Black medical schools in the United States had closed (and two more followed suit thirteen years later). The Report was explicit in its racism. The document assumed an audience of white physicians who believed they were racially superior to Black doctors. Flexner argued that most Black medical schools did not meet his standards but that training some Black physicians was necessary in order to treat Black patients. “The negro must be educated not only for his sake, but for ours,” he wrote. As Ann Steincke and Charles Terrell have described, the education of Black doctors served the “purpose of protecting whites” because it ensured that white doctors would not have to treat Black patients, whom Flexner felt were a “source of infection and contagion.” He also stipulated that Black doctors should be trained in “hygiene rather than surgery” so that they could use sanitarian principles to “civilize” their Black patient community.

While Flexner himself believed that women could and should pursue medicine as a career, his report nonetheless resulted in the closure of women’s medical schools. As documented in Regina Markell Morantz-Sanchez’s Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine (1985), most of the schools that remained open after the Flexner Report also refused to accept women as students.

The AMA’s vision of the prototypical doctor was someone who looked like its members: a well-educated and well-off white man who practiced medicine according to scientific principles.

One of the primary consequences of the Flexner Report, then, was to increase the prestige of medical practice by associating it with the powerful identity markers of whiteness, masculinity, and wealth. By the 1930s, 95 percent of American doctors were white men, and some 60 percent were members of the AMA. The effects of this are still with us. White physicians continue to dominate the AMA, particularly its leadership, along with academic medicine generally in the United States. In 2008, almost a hundred years after the Flexner Report, the AMA officially apologized to the National Medical Association, the preeminent professional organization for Black physicians, for its history of racism.

The AMA’s white supremacist orientation toward the profession was accompanied by an economic vision that centered on the free market. The organization encouraged physicians to act as business owners by managing their private clinical practices and employees, who might include nurses, technicians, and administrators. This was a stark shift for a profession that had previously been organized around house calls.

Indeed, the AMA emphasized the need for physicians’ autonomy and independence in their work. For example, physicians individually determined the costs of the services they provided, as well as the hours they worked. Issues of medical licensing and censure were determined by boards and committees composed of other physicians, as opposed to external oversight from government bureaucrats. The medical profession justified its independence by arguing that medicine was not an ordinary job. It was a noble vocation based on a deep-seated trust between a patient and their doctor that transcended the base commercialism of other work. The AMA’s “respectable” image of the American doctor as a white, affluent man was intended to reinforce the sense that physicians were trustworthy and moral professionals, capable of regulating their own behavior and that of their profession.

Critics, however, questioned the AMA’s integrity, insisting that the organization prioritized physicians’ wealth over patients’ health. By the 1930s some Americans—about 10 percent by the end of the decade—were buying into private health insurance plans, particularly to cover the cost of expensive hospital care. This change represented a private sector alternative to nationalized health care. But doctors still found it troubling, because it threatened the fee-for-service model touted by the AMA, in which patients paid for care out of pocket.

The vision of the doctor as an elite professional was designed to oppress and exclude marginalized people, not lift them up. We should not be surprised that it continues to function this way today.

In 1934 the AMA House of Delegates spoke out against private insurance, stating that “no third party must be permitted to come between the patient and his physician in any medical relation.” This position proved to be a miscalculation. In 1943 the Supreme Court decided against the AMA and ruled that its opposition to private insurance was “in restraint of trade” and therefore constituted a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act; the AMA was fined $2,500. The more severe punishment, according to Morris Fishbein, then the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, was that the AMA had been convicted “in the eyes of the people as being a predatory, antisocial monopoly.”

In spite of these setbacks, physicians and historians have often referred to the mid-twentieth century as the “Golden Age” of American medicine. It was a period when medical breakthroughs—including penicillin and the polio vaccine—and a subsequent decline in deaths from infectious disease earned the medical profession widespread public respect and cultural authority. But that prestige was not just rooted in its technological advancements. It was also based on a profoundly sexist, racist, and classist understanding of who would make a “good doctor.” This history continues to impact the diversity and priorities of American medicine today.

• • •

The AMA Stands Against Nationalized Health Care

From the AMA’s perspective, the biggest threat to medical independence—and to their own power—has been the push for nationalized health care. In fact, the AMA’s decision to eventually support private insurance was a concession, one that they hoped would dissuade the public from supporting “socialized medicine.” In the 1940s and ’50s Congress debated a series of proposals for national health insurance. In response, the AMA hired a public relations firm, Whitaker and Baxter, to sway public opinion in favor of private health insurance. Relying on inflammatory language, Whitaker told a meeting of physicians that “Hitler and Stalin and the socialist government of Great Britain have all used the opiate of socialized medicine to deaden the pain of lost liberty and lull the people into non-resistance.” The campaign cost the AMA $5 million dollars, but it succeeded in sinking the proposed legislation. And it convinced at least some Americans that nationalizing health care would compromise their “sacred right” to choose their own physician.

From the AMA’s perspective, the biggest threat to medical independence—and to their own power—has been the push for nationalized health care. Its opposition to nationalized health care endures to this day.

By the 1960s the medical profession’s fierce commitment to doctors’ independence had contributed to soaring health care costs. The situation was so severe that John F. Kennedy made it a campaign issue. The AMA was able to derail his initial attempt to create a public insurance program for the elderly, in part by engaging famous actor and budding politician Ronald Reagan as a spokesperson. After Kennedy’s assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson was able to push through legislation creating Medicare and Medicaid, much to the disappointment of the AMA, who initially threatened to boycott the programs.

Patients also began vocally challenging medical authority. The 1970s saw the emergence of the women’s health movement, which criticized the paternalism of doctors who felt they could—and should—make decisions about women’s bodies. Movements for racial justice, including the Black Panthers and Young Lords, pointed to the health disparities generated by manifestations of structural racism, including poverty, housing insecurity, food scarcity, and police brutality. These activist organizations imagined and implemented community-based initiatives, including free clinics and school lunch programs, which provided care and support for those neglected by the medical profession. These economic and cultural forces challenged physicians’ singular authority over matters of health and drew attention to the inequalities that resulted from the private fee-for-service model.

The AMA’s opposition to nationalized health care endures to this day. And just as the AMA had hoped, medicine remained a capitalist enterprise. But in hindsight, professional medical societies’ concern about the threat that “socialized medicine” posed for doctors’ independence was somewhat misplaced. At the turn of the twenty-first century, it wasn’t “Big Government” or the political left that would change the conditions of doctors’ labor, but a for-profit, neoliberal system of health care delivery called “managed care.”

• • •

The Rise of Managed Care

By the end of the 1970s, economists argued that the expansion of health care reflected a broader shift in the U.S. economy away from manufacturing and toward service-oriented industries. As health care became more profitable, and more profit-driven, insurance companies and corporations looked for ways to carve out larger and larger slices of the lucrative health care pie. The outcome of this process was a new system of health care delivery that has become known as “managed care.”

Managed care became a national priority after the passage of the Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Act under President Richard Nixon in 1973. The original and nominal intent was to control costs while improving the quality of care. Corporations and neoliberal policy makers in the 1980s argued that managed care approaches could reduce the inflation of medical costs by decreasing unnecessary hospitalizations, increasing competition in the health care market, and pushing providers to reduce prices. Today this approach is ubiquitous: 90 percent of Americans are enrolled in plans with some form of managed care.

The rise of managed care has dramatically transformed the conditions of physicians’ labor—ensuring that American medicine is oriented around profits, not patients.

In fact, instead of leading to a reduction in health care costs, managed care has further ensured that American medicine is oriented around profits, not patients. To cut costs, some companies began denying essential medical services, providing low-quality care, or refusing to accept sick or poor individuals in their plans. The number of uninsured Americans continues to be a problem. And unsurprisingly, the corporatization of health care has led to consumer pushback. Polling consistently shows that Americans believe that managed care has resulted in less time with doctors and subpar treatment. COVID-19 has further exposed the deep inequalities created and perpetuated by our for-profit health care system, as Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people suffer disproportionately from the coronavirus.

This story might be familiar to many Americans, most of whom will have experienced some features of managed care firsthand. What might be less obvious, however, is how dramatically managed care has transformed the conditions of physicians’ labor. The nostalgia that many doctors feel today for the “Golden Age” of medicine is related, at least in part, to the impact of managed care on their autonomy. Private practice might once have generated profits, but it was not subject to a neoliberal managerial ethos. Managed care, meanwhile, involves a complex financial system that confounds both doctors and patients while still exerting control over who receives care, what kind of care they are entitled to, and how much that care costs.

Physicians have thus, in large part, lost control of the means of production. The American media, and medical education itself, tend to project an image of doctors as the leaders in clinical care decision-making. But doctors today are more often employees of large hospital systems and staffing corporations owned by private equity firms. They are managed by an upper administrative class of hospital executives, who make decisions about where, when, and how doctors work. Hospital officials collaborate with insurance companies to manage clinical practice to cut costs (e.g., by restricting diagnostic testing and limiting specialist visits) and thus increase profits. The number of such hospital administrators—generally an executive class trained in business rather than medicine—has shot up a staggering 3,200 percent in the last forty years. At the same time, the number of doctors with an independent practice has plummeted. Today only a third of doctors are independent, down from almost 60 percent twelve years ago.

Doctors did not passively accept the changing conditions of their labor. In the early 1970s, some suggested unions: one survey found that as many as 61 percent of physicians supported unionization. A number of physician’s unions emerged during this period to combat the dwindling autonomy of the American physician. One of the few to survive today is the California-based Union of American Physicians and Dentists (UAPD), founded by Dr. Sanford Marcus in 1972. Marcus became a union activist when his hospital was in the process of establishing an HMO. As a physician, he had not been asked for his input and was furious to suddenly find that he had to “take orders” from hospital administrators with no medical training.

While doctors’ labor has shifted under managed care, their political consciousness remains stuck in the Golden Age—nostalgia for the image of the autonomous, self-employed, white collar professional.

But as a whole, physician’s unions failed to take off after this brief moment. Today the UAPD has only 4,000 members. In contrast, nurses have a history of unionization dating back to 1946, and over a fifth of American nurses today are members of a union. The cost constraints associated with managed care have forced nurses to care for more patients than in the past. And those patients are proportionately sicker, because insurance companies and HMOs have limited access to hospital care to only the sickest patients. However, unlike doctors, nurses have embraced unionization to protect themselves from the workplace demands associated with managed care. At the turn of the twentieth-first century, a greater proportion of nurses were members of unions than that of the overall workforce in the United States. Nursing unions have successfully negotiated minimum staffing levels, nursing practice committees, and greater nurse input in patient care decision-making. At the legislative level, nursing unions have worked to establish nurse-to-patient staffing ratios and to ban mandatory overtime in some states—protections not afforded to doctors. And amid this pandemic, unions of nurses have appealed to regulatory bodies, such as OSHA, to protect their workers in hospitals that lack adequate personal protective equipment.

Throughout its history the AMA has vociferously opposed the formation of physician unions, precisely because unionization would undercut the sense of elitism that organized medicine cultivated during its “Golden Age.” As Michael Halberstam, a prominent cardiologist and author, wrote in 1973, that although “unionization would give us some temporary bargaining power, we’d pay for it in loss of prestige, influence. . . . Medicine is not just another way to earn a living. . . . it’s a profession.” Physicians’ resistance to seeing themselves as workers is also present in the long-standing debate over doctors’ right to strike. The AMA’s position, and that of most bioethicists, is that doctors can strike for the sake of patient care, but never simply to improve their own working conditions.

Even before COVID-19, physicians, like other workers, suffered stress related to working long hours in an emotionally taxing environment. Structural changes under managed care—including excessive documentation and bloated bureaucracies to facilitate billing—have contributed to staggering levels of occupational burnout. Primary care physicians, for example, often spend over half their workday on electronic medical records that facilitate reimbursement from insurance companies, instead of seeing patients. Each year, a quarter to a third of doctors report symptoms of depression. While reliable statistics on rates of suicide by profession are difficult to come by, estimates suggest that some four hundred physicians die by suicide in the United States each year, a rate twice that of the general population and higher than that of active duty U.S. military members. In the context of COVID-19, the risks to physicians’ wellbeing are even greater, as frontline care providers have been forced to work in environments without adequate protections for their physical or psychological health.

Unlike doctors, nurses have embraced unionization to protect themselves from the workplace demands associated with managed care.

While doctors’ labor has shifted under managed care, their political consciousness remains stuck in the Golden Age. Professional medical societies have refused to let go of their nostalgia for the twentieth-century image of the autonomous, self-employed, white collar professional. This is partly due to the fact that doctors still tend to come from upper-middle class families who may find the identity of the worker, and the labor politics that come with it, alien or even beneath them. Against the backdrop of high private tuition costs and low initial stipends in training, the average family that produces a doctor is in the top 20 percent of earners. Only 5 percent of medical students come from the lowest quintile of America’s income distribution.

The historical effects of racial exclusion from medical schools also persist. The lack of diversity in medicine was finally acknowledged in the early 1970s by the Association of American Medical Colleges, which set a goal of 12 percent enrollment of minority medical students for the 1975 class. This goal was not met in 1975 or at any point in the subsequent decade. And today, diversity in the medical profession remains a significant problem. Black or Hispanic people made up 30 percent of the U.S. population in 2019, but only 11.5 percent of medical school graduates and 10 percent of all practicing physicians.

The slow matriculation of these groups into medicine since the 1970s has led to discrimination in training environments that were designed to accommodate affluent, white men, and not to account for, much less address, workplace discrimination. Women and underrepresented minorities suffer disparities in both pay and professional promotion in academic medical centers. Especially at the level of leadership, the medical profession remains overwhelmingly white and has, by and large, rejected the activist tactics associated with movements for racial justice and worker’s rights.

• • •

Working Toward Justice in Medicine

COVID-19 should be a reality check for physicians. It shatters any illusion that doctors do not function as labor-for-profit in the current health care system. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the long-standing emphasis on individualism in the field of medicine, the physicians who have spoken up about unsafe working conditions during this pandemic have often been isolated whistleblowers, and many of them have faced retaliation from hospital administration or lost their jobs for speaking up about a lack of access to PPE. Reflecting on doctors’ lack of resistance to unsafe working conditions, the emergency medicine physician Steven McDonald recently wrote in The Atlantic, “This is not why I became a physician, but I did not resist, because I have ceased to expect appropriate support from administrators, institutions, and the government itself.”

McDonald is right. Doctors will not get sustained support from the government, hospital administration, or even their professional organization. But this does not mean that resistance is futile.

To engage in meaningful resistance, physicians will have to learn to see themselves differently. They must abandon any nostalgia for the elitism and moral superiority of their supposed Golden Age.

To engage in meaningful resistance, physicians will have to learn to see themselves differently. They must abandon any nostalgia for the elitism and moral superiority of their supposed Golden Age. While these values afforded the medical profession prestige and autonomy, they were also based on a racist, sexist, and classist system that continues to structure organized medicine and that prevents physicians from advocating for themselves or their patients. The elitism that doctors inherited from the previous century encourages individualism instead of collective organization. It prevents doctors from seeing themselves as workers who can learn from nurses and technicians, professions with generations of experience organizing for their rights. It casts the protest tactics associated with racial justice movements such as Black Lives Matter as “unprofessional,” “counter-productive,” or simply as outside of medicine’s purview. And amid this pandemic, doctors’ moral superiority encourages the harmful view that their deaths from COVID-19 are a “noble, heroic sacrifice,” instead of a tragic and preventable consequence of unsafe workplaces.

The vision of the doctor as an elite professional was designed to oppress and exclude marginalized people, not lift them up. We should not be surprised that it continues to function this way today. Doctors need to reimagine their collective identity to bring it in line with the political realities of the twenty-first century. American medicine is long overdue for a reckoning with its past. Doctors need to acknowledge and relinquish the violence engendered by their pursuit of prestige, so that they can organize to fight structural oppression.

This effort will not be led by the AMA or other professional medical societies. Instead, it is already beginning with a new generation of doctors, many of whom would have been excluded from the medical profession in the early twentieth century. They are the Black and Brown doctors-in-training who agitate with White Coats for Black Lives to fight racism in health care and who are inspired by the health activism of the Black Panthers and Young Lords from the 1970s. They are the first-generation doctors who work as street medics to support protests against police brutality, create mutual-aid programs to support their neighbors during this pandemic, and organize as union activists to stand in solidarity and protect workers’ rights in their hospitals. These leaders are experimenting with novel political tactics and strategies. They will forge a new understanding of what it means to pursue justice through medicine and, even more fundamentally, a new image of what it means to be a doctor.