Today marks three years since the passing of Aretha Franklin. Though she’s known as the “Queen of Soul,” Aretha was more than this, argues BR contributing arts editor Ed Pavlić. “She was a Black prophet,” as Amazing Grace, the long-lost film of her gospel album of the same name, reveals. Indeed, after viewing the movie, Reverend William Barber II told Variety that Aretha was “singing from not only her physical belly, but from the depths of history . . . not only out of her soul but out of the soul of the people.”

Pavlić goes on to note that to fully appreciate Amazing Grace one needs “a lesson in the origins of Black music, a tradition rich with complex and at times contradictory cultural and political power.” With this in mind, today’s reading list takes a short tour through this history: from the musician who arguably did more than any other to build the canon of American folk song, to Franklin’s contemporaries like Marvin Gaye—here remembered by “Sexual Healing” co-writer David Ritz—via Black feminist blues and Bessie Smith.

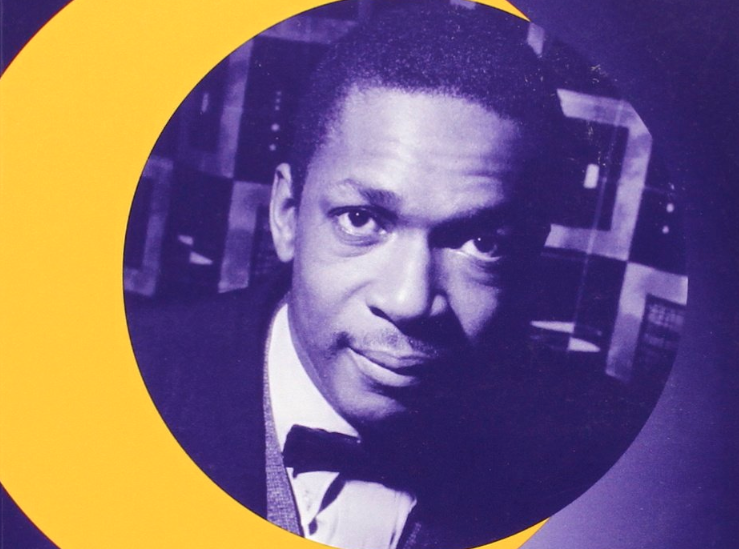

Many pieces in today’s list focus on Jazz, making mention of household names such as Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and other members of the “Sacred Black Masculine.” But less well-remembered artists also feature, with a recent essay exploring the seminal civil rights album We Insist! from Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Oscar Brown, Jr. “They refused the choice between great art and political art,” Michael Reagan writes, “embracing a new unity of social context, personal expression, and experimentation. . . . It is a lasting testament to the open expanse of struggle, the boundless horizon of Black liberation.”

But as renowned jazz musician Vijay Iyer noted in an interview with Robin D. G. Kelley, this liberatory legacy has been warped, repackaged as both fashionable and something to maintain distance from. “I think many people think I’m cool because of my proximity to Blackness—but also because I’m not actually Black, you know?” Iyer comments. “And that’s inextricable from the history of Black music in the United States being sold by white companies and appropriated by non-Black people, or inhabited in different ways by non-Black people, which is this sort of way of managing and selling proximity to Blackness without the guilt.”

Rap also has a fraught cultural heritage, as several authors in our archive have examined. In 1991, fresh from her coining of the idea of “intersectionality,” legal scholar Kimberlé W. Crenshaw turned to our pages to apply the concept to the controversy surrounding the hip hop group 2 Live Crew, then facing prosecution for their misogynistic lyrics. While recognizing that their album “objectified Black women and represented them as legitimate targets for sexual violence,” Crenshaw argued that a Black feminist response “must also consider whether an exclusive focus on issues of gender risks overlooking aspects of the prosecution of 2 Live Crew that raise serious questions of racism.”

Two decades later and the criminalization of Black art has still not improved. Indeed, rap lyrics now appear in murder and assault trials where prosecutors try and use them to win cases despite flimsy evidence. “No other art form, musical or otherwise, is treated this way in court,” remarked lawyer Andrea L. Dennis and liberal arts scholar Erik Nielson in a 2019 essay. “Society has long viewed Black art as a threat and turned to the criminal justice system to control Black speech and creative endeavors.”

But all is not lost. As last summer’s rebellions show, Black popular music is also being recognized for its ability to shape everyday activism, protest, and resistance, utilizing digital platforms such as TikTok to create communities of mutually invested participants. Looking toward the future, we end with two essays that focus on the contributions made to Afrofuturist culture by women musicians—an important task, given that discussions of Afrofuturism often privilege male figures. Combining themes of cyberspace and science with celebrations of Blackness and queerness, artists like Janelle Monáe and Labelle “beam a progressive vision of an emancipated future.”

Through online fan communities and digital platforms like TikTok, popular music is finding powerful new ways to shape everyday activism, protest, and resistance.

Amazing Grace, the long-lost film of Franklin’s gospel album, offers a lesson in the deep connections between gospel and soul music.