American Radicals establishes the truly riotous nature of nineteenth-century activism, chronicling the central role that radical social movements played in shaping U.S. life, politics, and culture. Holly Jackson’s cast of characters includes everyone from millenarian militants and agrarian anarchists to abolitionist feminists espousing Free Love. Rather than rehearsing nineteenth-century reform as a history of bourgeois abolitionists having tea and organizing anti-slavery bazaars for their friends, Jackson offers electrifying accounts of Boston freedom fighters locking down courthouses and brawling with the police. We learn of preachers concealing guns in crates of Bibles and sending them off to abolitionists battling the expansion of slavery in the Midwest. We glimpse nominally free black communities forming secret mutual aid networks and arming themselves in preparation for a coming confrontation with the state. And we find that antebellum activists were also free lovers who experimented with unconventional and queer relationships while fighting against the institution of marriage and gendered subjugation. Traversing the nineteenth-century history of countless “strikes, raids, rallies, boycotts, secret councils, [and] hidden weapons,” American Radicals is a study of highly organized attempts to bring down a racist, heteropatriarchal settler state—and of winning, for a time.

Reframing the nineteenth-century United States as a war society, Jackson helps us to see social movements—from abolitionism and labor to feminism and early environmental activism—as a continuation of the Revolutionary War by other means.

Jackson illuminates how the creative and performative qualities of nineteenth-century public protest sought to interrupt the status quo. When, in 1854, 50,000 people showed up in Boston to protest the return of fugitive slave Anthony Burns back to slavery, an act authorized by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, protestors staged an elaborate funeral for democracy: black crepe adorned the street, a huge U.S. flag was hung upside down, and a coffin labeled “Liberty” was hung out of a building while the crowd below shouted “Shame!” at federal troops deployed to transport Burns back to the South. Then, as now, the threatening spectacle of both police and military were marshalled as a “bellicose display” intended to intimidate the massive political—and creative—energy of protestors who dared to question the nation’s daily acts of anti-democratic violence and violation of its own founding documents.

The antebellum United States was a deeply unstable formation, suffused with the symbolic and physical traces of the Revolutionary War and, government officials feared, teetering on the verge of anarchy. Reframing the nineteenth-century United States as a war society, Jackson helps us to see social movements—from abolitionism and labor to feminism and early environmental activism—as a continuation of the Revolutionary War by other means. In other words, the militancy of the American Revolution lived on in the many factions and revolts that fomented among the nation’s multitude.

The United States sought to reaffirm its sovereignty through routine celebrations of its independence from Britain. But a militaristic society always celebrating its freedom from tyranny is a powder keg: it constantly threatened to tip over into rebellion against a standing government that many deemed illegitimate. In this way, when African Americans in Boston dressed up and walked in parades celebrating the abolition of the slave trade, they weren’t participating in a quaint ritual that reaffirmed the U.S. social order: they were reminding the nation of its recent betrayal of its black citizens, who took up arms and joined the fight against the British in the name of freedom but still remained in chains. Their presence in the streets must have registered to onlookers as a haunting, insurgent body, in formation and ready to revolt, to start the nation anew or to jettison it for a completely new form of governance.

Activists across various reform movements continued to return to the country’s founding documents—notably the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence—as well as the events of the Revolutionary War as inspiration in their struggle to dismantle structures of exploitation and oppression. This was not based in some sense of idealism about the nation’s character or potential: for most nineteenth-century radicals, especially those dispossessed, displaced, and held in captivity, the nation was helpful only insofar as it was a commonplace for revolutionary rhetoric. Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson calls the Constitution “one of the most successful counterrevolutionary schemes ever devised,” but notes that, as an ur-fetish, it has often served as a site of social cohesion. American Radicals is, in many ways, a history of what was done with that founding fetish.

• • •

Sex radicalism was prominent within the broader terrain of anti-slavery. Indeed, abolitionists were often discredited in the press for their reputation as ‘queers.’

Jackson’s story of collective action is told, somewhat paradoxically, through a set of individual biographies. For example, she traces black intellectual and activist Martin Delany’s journey from antebellum militancy to a baffling postwar conservatism. Readers will also learn about the inspiring rise and then tragic downfall of Franny Wright, a European heiress who believed so strongly in the ideals espoused during the American Revolution that she moved to the United States to help bring about the nation’s unfulfilled promise of freedom and liberty for all. A supporter of Free Love, she agitated for the abolition of marriage, became a notorious figure in the press, and founded a utopian settlement on indigenous lands in Nashoba, Illinois, that ultimately reproduced the gravest errors of the nation’s founders.

American Radicals is particularly attentive to the long and storied career of William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist leader and staunch radical pacifist who was unrelenting in his hatred of the U.S. government. For Garrison, the United States was an unsalvageable formation. Garrison burned the Constitution before a Boston crowd; he rejoiced when the South seceded from the Union; he, like other members of the Non-Resistance movement, did not vote, pay taxes, or serve in the military. Amid the intensification of anti-black state violence and surveillance in the 1850s, along with the expansion of slavery into the Midwest, Garrison’s political commitments were pushed to the brink: at a speech in Boston after John Brown’s execution, Garrison called out to his fellow “Non-Resistants,” dwindling in number by the 1850s, but then went on to wish success to every slave rebellion in the South. This was an incredible reversal for Garrison, who had preached total pacifism since the 1830s. Garrison ultimately locked arms with abolitionists who advocated the use of force as he became increasingly aware that the United States was never going to voluntary give up its reliance on enslaved labor.

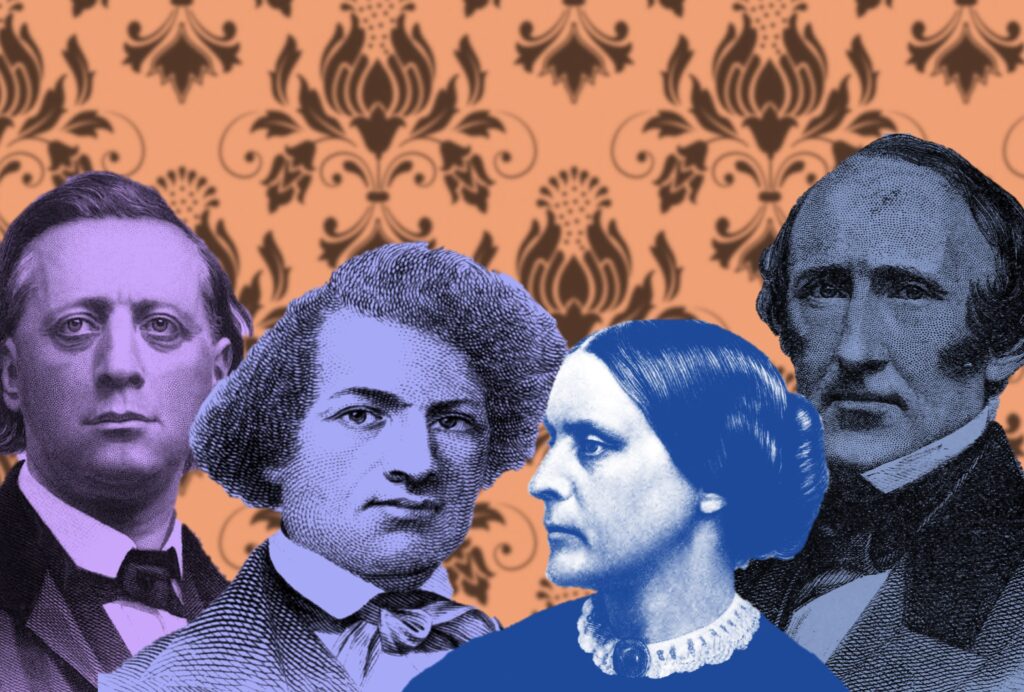

Jackson’s book highlights the degree to which nineteenth-century social movements were deeply interconnected, drawing inspiration from one another and often sharing members, even meeting space. Spanning from the beginning of organized abolition in the 1830s to the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, American Radicals explores not just coalitional successes, but also the critical moments when alliances broke down. For example, Jackson details the splintering between anti-racism and suffrage after the war, when white suffragists sought to mainstream their struggle by disconnecting it from racial equality. At the 1869 Equal Rights Association meeting in New York, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton showed up to face down Frederick Douglass, who had been a longstanding defender of suffrage but was critical of members of the movement who had turned their back on black Americans. When Douglass stood up to deliver his remarks at the meeting, Anthony jumped to her feet and charged down the aisle toward Douglass. Douglass, in turn, raised his hand while declaring, “No, no Susan.” Susan sat down.

Jackson’s account of the 1850s is especially energetic. The decade witnessed an intensification of anti-abolitionist and anti-black violence, growing sectionalist discord, the territorial expansion of slavery, and the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. The shift to direct action and use of force among abolitionists in the 1850s shines through in Jackson’s meticulous, play-by-play account of John Brown’s plot to capture the national armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and thus (he hoped) begin an insurrection that would end slavery and topple the U.S. government. Jackson’s account of the raid on Harpers Ferry as a highly orchestrated but also deeply collective action, involving many networks of black abolitionists, allows her to subsequently reconceptualize the beginning of the Civil War as one of Confederate insurgency. In the aftermath of the state’s violent suppression of the rebellion, Confederate insurgents captured the arsenal at Harpers Ferry for themselves. This is a helpful reminder that well before the Civil War was officially declared, violent, extralegal battles were being waged directly between abolitionists and white supremacists. In other words, by the time the Civil War was declared, it had already been underway for years.

• • •

Sex scandals plagued abolitionists, many of whom were committed to what was then called Free Love: they denounced their marriage vows, had affairs, and were polyamorous.

American Radicals is perhaps most groundbreaking for how it illuminates the place of sexual freedom within the history of nineteenth-century reform. Sex radicalism, experiments in communal living, and free love were prominent within the broader terrain of anti-slavery, labor, anarchist, and feminist activism in the nineteenth century. Yet histories of abolition have long sanitized the movement, overlooking the extent to which anti-slavery activists were often also involved with movements to abolish marriage and dismantle heteropatriarchy. Indeed, abolitionists and other reformists were often discredited in the press for their fanaticism and for their reputation as “queers.”

Sex scandals plagued abolitionists such as Fanny Wright and Henry Ward Beecher. Many were committed to what was then called Free Love (disconnected in time though not in spirit from the Free Love movement of the 1960s): they denounced their marriage vows, had affairs, were polyamorous. Jackson takes political and erotic desire—and their intersection—seriously, in a way that has rarely been the case for scholars of abolition. As a result, American Radicals liberates abolitionist history from the stuffy confines of Civil War historiography, a tradition that has long leaned toward nationalism and sexual normativity. So doing, Jackson not only offers a compelling revision of abolitionist history, but offers a long-hidden genealogy for today’s queer and trans abolitionists.

Jackson notes that many reformers cross-dressed or were ostentatious in their style: they wore bloomers or dashikis, full beards, and even flowers in their hair. Describing what she dubs “reform weirdos,” Jackson draws out the countercultural dimensions of nineteenth-century reform and its clear connections to more recent iterations of U.S. counterculture, perhaps most obviously the blending of the anti–Vietnam War and hippie movements. She reminds us that in memorializing reform history and venerating individual heroes, the “weirder” elements of nineteenth-century reform have been “edited out.”

At the same time, Jackson’s account of antebellum bohemianism drives home how a movement can simultaneously be an activist vanguard and contain within itself the ugliest of mainstream bigotry. Jackson’s exploration of experiments in communal and intentional living helps us to recognize such utopias as white utopias. In addition to reproducing bourgeois social arrangements and entertainments, they often reproduced divisions of labor that were patriarchal and racist. Jackson does not shy away from the racist underbelly of nineteenth-century communes, offering a frank account, for example, of how, when Fanny Wright left Nashoba, she put a cruel and abusive overseer-type in charge. He whipped black residents, coerced them into plantation labor, and fueled a culture of sexual terror. Here, the transformation of an idyllic agricultural paradise into a racial dystopia is a reminder of the disingenuity with which some communal experiments sought to fulfill and extend the American experiment. The sadism of Wright’s inheritor also reveals the continuity between the (white) commune and the plantation, as a space that gave free reign to white libertinism, sadism, and the exploitation of black flesh.

Jackson offers a highly original account of postwar Reconstruction as a strategy aimed at conscripting the activist energy and anarchic spirit of the antebellum period toward rebuilding the state.

In Jackson’s account, Free Love at times also feels both really white and really repressed. Undergirded by eccentric theories of self-denial and bodily control, we see that nineteenth-century reform was also animated by (settler) fantasies of mastery and by anxieties about excess, contamination, and miscegenation. In these moments, Free Love’s connection to an emerging regime of eugenics become clear. What is less clear from Jackson’s work is how activists of color themselves pursued their utopian visions in ways that were inadequately documented by institutional archives. What, in other words, is the history of the black commune? Of black—and Native—free love, gendered experimentation, and sex radicalism in the nineteenth century? That book has yet to be written.

• • •

So what happened to all of this energy and organizing around radical social causes? How was the end result a Victorian U.S. society remembered, not altogether incorrectly, for its conformism? Jackson offers a highly original account of postwar Reconstruction as a strategy aimed at conscripting the activist energy and anarchic spirit of the antebellum period toward rebuilding the state. In this account, Reconstruction’s failure is already written on the wall by as early as 1866, when former free lovers, labor organizers, and abolitionists became officers in and representatives of the reunited state: “Men formerly involved with socialist communes and treasonous plots were now leaders of the federal project that would shape the American future—proof of their vindication but also their containment.”

Across the board, this was a moment when former abolitionists and reformists saw an opportunity to make strategic and practical gains at the federal level. But in the name of visibility, recognition, and concrete political gains, reformers jettisoned the coalitional politics, intersectionality, and radical imagination that had once infused the movement. A handful of figures, including Wendell Phillips, critiqued former movement leaders for selling out, while figures such as Delany decided to play what they thought of as the “long game”—in Delany’s case, ultimately becoming such an accommodationist that he supported former Confederates and segregationists for office. Even Garrison, a “hardcore Non-Resistant,” “now felt confident handing his life’s work over to the state, going so far as to declare that ‘the American army was now the American antislavery society.’”

Since its founding the nation has trafficked in a language of plurality and diversity while policing and criminalizing actual acts of sexual, gendered, and racial freedom because of their insurgent potential.

When Jackson offers vivid descriptions of roundups and executions in the wake of racial rebellion; of draconian ID laws meant to hobble African Americans; of the raiding of queer salons and Free Love boarding houses; of national gaslighting campaigns and the emboldening of white supremacists from a white supremacist White House, it’s hard not to see connections to the suppression of U.S. protest—and social life—in the twenty-first century. As it turns out, since its founding the nation has trafficked in a language of plurality and diversity while policing and criminalizing actual acts of sexual, gendered, and racial freedom because of their insurgent potential.

Though deeply rooted in the historical record, Jackson’s book also helps illuminate the terrors of our own moment as ones related to transition rather than apocalypse. (It’s a common error: Walter Benjamin describes historical moments such as these as ones in which “the dreaming collective” mistakes “the decline of an economic era” for the “end of the world.”) To collapse a world-historical transitional phase of capitalism with the end of the world itself would indeed be a mistake. But it would also be a missed opportunity. Or as Jackson writes, “One upside to the failure of the world is that other worlds become imaginable.” In some ways, Jackson’s is a history that asks activists to persist in the face of likely failure, and even imminent doom. She reminds us that some experiments in abolition were successful precisely because they failed: the failure of Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry was a lightning rod that ignited the start of the Civil War.

In this way, American Radicals stands as a surprisingly non-instrumental history of U.S. social movements. It asks us to pay attention to political experiments whose effects can’t objectively be measured and to remember that all liberal reform now ensconced in U.S. law began as radical demands. It advocates for a slower and more thoughtful relationship to the history of radicalism. At the same time, American Radicals feels so electrifying and alive, so textured and so real, it is a book that asks to be used. A deep dive into the archives of U.S. radicalism, it doubles as a tool to be mobilized by radical actors, collectives, and dreamers today. Against the grain of our apocalyptic-feeling present, American Radicals asks us not to despair, but to organize.