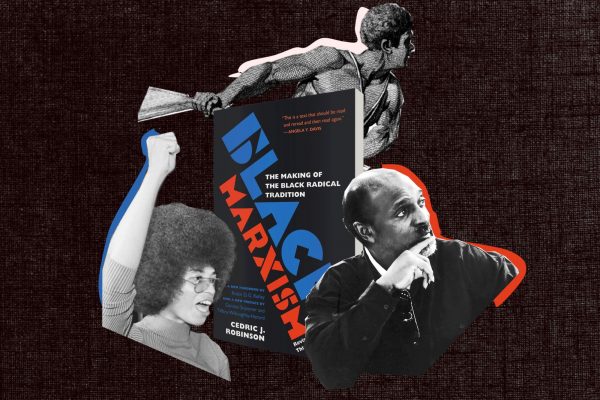

The inspiration to bring out a new edition of Cedric Robinson’s classic, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, came from the estimated 26 million people who took to the streets during the spring and summer of 2020 to protest the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and the many others who lost their lives to the police. During this time, the world bore witness to the Black radical tradition in motion, driving what was arguably the most dynamic mass rebellion against state-sanctioned violence and racial capitalism we have seen in North America since the 1960s—maybe the 1860s. The boldest activists demanded that we abolish police and prisons and shift the resources funding police and prisons to housing, universal healthcare, living-wage jobs, universal basic income, green energy, and a system of restorative justice. These new abolitionists are not interested in making capitalism fairer, safer, and less racist—they know this is impossible. They want to bring an end to “racial capitalism.”

The threat of fascism is no longer rhetorical, a hollow epithet. It is real.

The state’s reaction to these protests has also brought us to the precipice of fascism. The organized protests in the streets and places of public assembly, on campuses, inside prisons, in state houses and courtrooms and police stations, portended the rise of a police state in the United States. For the past several years, the Movement for Black Lives and its dozens of allied organizations warned the country that we were headed for a fascist state if we did not end racist state-sanctioned violence and the mass caging of Black and brown people. They issued these warnings before Trump’s election. As the protests waned and COVID-19 entered a second, deadlier wave, the fascist threat grew right before our eyes. We’ve seen armed white militias gun down protesters; Trump and his acolytes attempt to hold on to power despite losing the presidential election; the federal government deploy armed force to suppress dissent, round up and deport undocumented workers, and intimidate the public; and, most recently the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol by members of the alt-right, racists, Neo-Nazis, and assorted fascist gangs whose ranks included off-duty cops, active military members, and veterans. The threat of fascism is no longer rhetorical, a hollow epithet. It is real.

The crossroads where Black revolt and fascism meet is precisely the space where Cedric’s main interlocutors find the Black radical tradition. Black Marxism is, in part, about an earlier generation of Black antifascists, written at the dawn of a global right-wing, neoliberal order that one political theorist called the era of “friendly fascism.”

Black Marxism was primarily about Black revolt, not racial capitalism.

What did Robinson mean by the Black radical tradition, and why is it relevant now? Contrary to popular belief, Black Marxism was primarily about Black revolt, not racial capitalism. Robinson takes Marx and Engels to task for underestimating the material force of racial ideology on proletarian consciousness, and for conflating the English working class with the workers of the world. In his preface to the 2000 edition of Black Marxism, Cedric wrote, “Marxism’s internationalism was not global; its materialism was exposed as an insufficient explanator of cultural and social forces; and its economic determinism too often politically compromised freedom struggles beyond or outside of the metropole.” It is a damning observation. Many would counter by pointing to Marx’s writings on India, the United States, Russia, slavery, colonialism, imperialism, and peasants. Others would argue that Marx himself only ever claimed to understand capitalist development in Western Europe. But because neither Marx nor Engels considered the colonies and their plantations central to modern capitalist processes, class struggles within the slave regime or peasant rebellions within the colonial order were ignored or dismissed as underdeveloped or peripheral—especially since they looked nothing like the secular radical humanism of 1848 or 1789.

Cedric’s point is that Marx and Engels missed the significance of revolt in the rest of the world, specifically by non-Western peoples who made up the vast majority of the world’s unfree and nonindustrial labor force. Unfree laborers in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the islands of the sea were producing the lion’s share of surplus value for a world system of racial capitalism, but the ideological source of their revolts was not the mode of production. Africans kidnapped and drawn into this system were ripped from “superstructures” with radically different beliefs, moralities, cosmologies, metaphysics, and intellectual traditions. Robinson observes,

Marx had not realized fully that the cargoes of laborers also contained African cultures, critical mixes and admixtures of language and thought, of cosmology and metaphysics, of habits, beliefs and morality. These were the actual terms of their humanity. These cargoes, then, did not consist of intellectual isolates or decultured blanks—men, women, and children separated from their previous universe. African labor brought the past with it, a past that had produced it and settled on it the first elements of consciousness and comprehension.

With this observation Robinson unveils the secret history of the Black radical tradition, which he describes as “a revolutionary consciousness that proceeded from the whole historical experience of Black people.” The Black radical tradition defies racial capitalism’s efforts to remake African social life and generate new categories of human experience stripped bare of the historical consciousness embedded in culture. Robinson traces the roots of Black radical thought to a shared epistemology among diverse African people, arguing that the first waves of African New World revolts were governed not by a critique rooted in Western conceptions of freedom but by a total rejection of enslavement and racism as it was experienced. Behind these revolts were not charismatic men but, more often than not, women. In fact, the female and queer-led horizontal formations that are currently at the forefront of resisting state violence and racial capitalism are more in line with the Black radical tradition than traditional civil rights organizations.

Africans chose flight and marronage because they were not interested in transforming Western society but in finding a way “home,” even if it meant death. Yet, the advent of formal colonialism and the incorporation of Black labor into a fully governed social structure produced the “native bourgeoisie,” the Black intellectuals whose positions within the political, educational, and bureaucratic structures of the dominant racial and colonial order gave them greater access to European life and thought. Their contradictory role as descendants of the enslaved, victims of racial domination, and tools of empire compelled some of these men and women to rebel, thus producing the radical Black intelligentsia. This intelligentsia occupies the last section of Black Marxism. Robinson reveals how W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, and Richard Wright, by confronting Black mass movements, revised Western Marxism or broke with it altogether. The way they came to the Black radical tradition was more an act of recognition than of invention; they divined a theory of Black radicalism through what they found in the movements of the Black masses.

The final section has also been a source of confusion and misapprehension. Black Marxism is not a book about “Black Marxists” or the ways in which Black intellectuals “improved” Marxism by attending to race. This is a fundamental misunderstanding that has led even the most sympathetic readers to treat the Black radical tradition as a checklist of our favorite Black radical intellectuals. Isn’t Frantz Fanon part of the Black radical tradition? What about Claudia Jones? Why not Walter Rodney? Where are the African Marxists? Of course Cedric would agree that these and other figures were products of, and contributors to, the Black radical tradition. As he humbly closed his preface to the 2000 edition, “It was never my purpose to exhaust the subject, only to suggest that it was there.”

Black Marxism is neither Marxist nor anti-Marxist. It is a dialectical critique of Marxism that turns to the long history of Black revolt.

The Black radical tradition is not a greatest hits list. Cedric was clear that the Black intellectuals at the center of this work were not the Black radical tradition, nor did they stand outside it—through praxis they discovered it. Or, better yet, they were overtaken by it. And, as far as Cedric was concerned, sometimes the Black intellectuals about whom he writes fell short. Marxism was their path toward discovery, but apprehending the Black radical tradition required a break with Marx and Engels’s historical materialism.

Black Marxism is neither Marxist nor anti-Marxist. It is a dialectical critique of Marxism that turns to the long history of Black revolt—and to Black radical intellectuals who also turned to the history of Black revolt—to construct a wholly original theory of revolution and interpretation of the history of the modern world.

When the London-based Zed Press published Black Marxism in 1983, few could have predicted the impact it would have on political theory, political economy, historical analysis, Black studies, Marxist studies, and our broader understanding of the rise of the modern world. It appeared with little fanfare. For years it was treated as a curiosity, grossly misunderstood or simply ignored. Given its current “rebirth,” some may argue that Black Marxism was simply ahead of its time. Or, to paraphrase the sociologist George Lipsitz quoting the late activist Ivory Perry, perhaps Cedric was on time but the rest of us are late? Indeed, how we determine where we are depends on our conception of time.

We should think of the Black radical tradition as generative rather than prefigurative. The road is constantly changing.

Cedric took Marx’s historical materialism to task in part for its conception of time and temporality. From The Terms of Order to An Anthropology of Marxism, he consistently critiqued Marxism for its fidelity to a stadial view of history and linear time or teleology, and dismissed the belief that revolts occur at certain stages or only when the objective conditions are “ripe.” And yet there was something in Cedric—perhaps his grandfather’s notion of faith—that related to some utopian elements of Marxism, notably the commitment to eschatological time, or the idea of “end times” rooted in earlier Christian notions of prophecy. Anyone who has read “The Communist Manifesto” or sang “The Internationale” will recognize the promise of proletarian victory and a socialist future. On the one hand, Robinson considered the absence of “the promise of a certain future” a unique feature of Black radicalism. “Only when that radicalism is costumed or achieves an envelope in Black Christianity,” he explained in a 2012 lecture, “is there a certainty to it. Otherwise it is about a kind of resistance that does not promise triumph or victory at the end, only liberation. No nice package at the end, only that you would be free. . . . Only the promise of liberation, only the promise of liberation!”

“Only the promise of liberation” captures the essence of Black revolt and introduces a completely different temporality: blues time. Blues time eschews any reassurance that the path to liberation is preordained. Blues time is flexible and improvisatory; it is simultaneously in the moment, the past, the future, and the timeless space of the imagination. As the geographer Clyde Woods taught us, the blues is not a lament but a clear-eyed way of knowing and revealing the world that recognizes the tragedy and humor in everyday life, as well as the capacity of people to survive, think, and resist in the face of adversity. Blues time resembles what the anarchist theorist Uri Gordon calls a “generative temporality,” a temporality that treats the future itself as indeterminate and full of contingencies. In thinking of the Black radical tradition as generative rather than prefigurative, not only is the future uncertain, but the road is constantly changing, along with new social relations that require new visions and expose new contradictions and challenges.

Cedric reminded us repeatedly that the forces we face are not as strong as we think. They can be disassembled.

What we are witnessing now, across the country and around the world, is a struggle to interrupt historical processes leading to catastrophe. These struggles are not doomed, nor are they guaranteed. Thanks in no small measure to this book, we fight with greater clarity, with a more expansive conception of the task before us, and with ever more questions. Cedric reminded us repeatedly that the forces we face are not as strong as we think. They are held together by guns, tanks, and fictions. They can be disassembled, though that is easier said than done. In the meantime, we need to be prepared to fight for our collective lives.

Editors’ Note: This essay is adapted from the foreword to the third and updated edition of Black Marxism: The Making of a Radical Tradition, Copyright © 1983 by Cedric Robinson. Foreword Copyright © 2021 by Robin D. G. Kelley. Used by permission of the publisher.