The United States was made by its frontier. Today it is being unmade by its border. In his recent national address aimed at building public support for a border wall, Donald Trump called the current moment “a crisis of the heart and a crisis of the soul.” He is at least right about that, and it is a crisis a long time coming.

All nations have borders, and many today even have walls. But only the United States has had a frontier, or at least a frontier that has served as a proxy for human liberation, synonymous with the possibilities and promises of modern life itself and held out as a model for the rest of the world to emulate.

For over a century, the frontier has served as the defining myth of the nation’s identity, a wide-open threshold into the world and the future. According to the myth, expansion across the continent transformed Europeans into something new, into a people both coarse and curious, self-disciplined and spontaneous, practical and inventive, filled—as the frontier’s most influential theorist, historian Frederick Jackson Turner, put it in the late 1800s—with a “restless, nervous energy” and lifted by “that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom.” What became known as Turner’s Frontier Thesis—the argument that expansion across a frontier of “free land” created a uniquely U.S. form of political equality and individualism—placed a wager on the future.

For Turner, the ninety-ninth meridian, where the prairie meets the desiccated plains, stood for the symbolic beginning of the frontier. Beyond this line, tenacious, inventive men figured out ways to irrigate dry land and began to think of history as progress, as moving forward toward an ever more bountiful future. That was where the United States became liberal and internationalist, where it learned, as Walt Whitman wrote, how to “feed the world.” The Progressive Era journalist Frank Norris wrote in 1902 that he hoped territorial expansion would lead to a new kind of universalism, to a “brotherhood of man” in which Americans would recognize “the whole world is our nation and simple humanity our countrymen.”

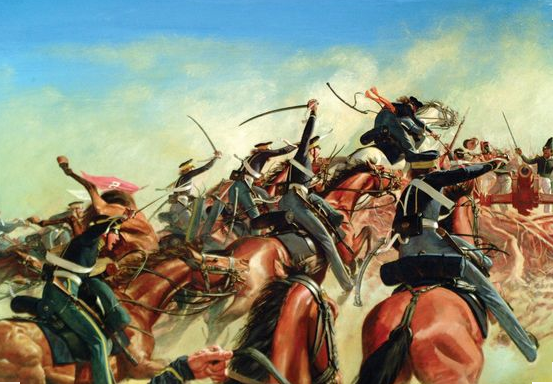

But the U.S. frontier was always also a border. (In fact, before the idea of the frontier was transformed into a site of existential creation, the word frontier simply referred to a political boundary or military front.) The history of that border as it moved, first from the Mississippi, then to the Sabine and Red Rivers, and finally to the Rio Grande and Pacific, is—as it passed over Native American homelands and large swaths of Spanish and Mexican territory—a history of nearly unimaginable terror and grief, land theft, ethnic cleansing, forced marches, concentrated resettlement, war, torture, and rape. These prefigured the great genocides and dispossessions of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, among them Europe’s Scramble for Africa, the Holocaust, the Nakba, and the Indian Partition.

For the first half of the nineteenth century, the U.S. border moved west as part of the great domestic struggle over labor, as the free and slave sections of the country pushed outward—the first hoping to contain the second, the second looking to break free of the first. The Civil War settled that fight, and then border-frontier expansion continued as a unified campaign.

As the United States expanded, first into the West and then into the world, frontier theorists such as Turner—faced with Jim Crow, anti-miscegenation and nativist exclusion laws, the resurgent KKK, Mexican workers being lynched in Texas, the military still massacring Native Americans, and deadly counterinsurgencies in the Caribbean and Pacific—promised that the racism and brutality of outward expansion would soon be relegated to the margins of the nation. Nearly all of these theorists, especially Turner, were Americanized Hegelians, arguing that history moved forward dialectically. That is, they believed that the unilateral will to power that drove the United States to establish continental dominance would help create a world of universal law, which, if allowed to mature, would then establish dominance over Washington’s will to power.

For instance, President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid reader of Turner, had, as an historian, celebrated border vigilantism. The posse, the lynching rope, and even torture, he believed, were “healthy for the community.” Eventually such rough justice, Roosevelt thought, would evolve into more rational forms of state-administered jurisprudence. And as president, he signed some of the world’s first multinational legal treaties, attempting to subordinate the United States to international law. He couldn’t. At home, he couldn’t even subordinate the vigilantes he had earlier hailed. Faced with what he called a lynching “epidemic,” Roosevelt blamed African American men: “The greatest existing cause of lynching,” he said in 1906, “is the perpetration, especially by black men, of the hideous crime of rape.” White men forced into retributive lynching, Roosevelt said, debase themselves, falling to “a level with the criminal.” “Lawlessness,” Roosevelt said, “grows by what it feeds upon; and when mobs begin to lynch for rape they speedily extend the sphere of their operations and lynch for many other kinds of crimes.”

And, as one president after another has learned, the easiest way to control the sphere of domestic extremism is to extend the sphere of outward expansion, to channel the passions beyond the frontier. So Roosevelt pushed forward.

To say that frontier expansion helped “marginalize” extremism is not just a metaphor or a turn of phrase. One strain of Anglo-Saxonism was literally pushed to the margins, to the 2,000 mile border running from Texas to southern California. Other kinds of racism found expression throughout the whole of the country, from lynching and Jim Crow to northern segregation. White supremacy was also kept sharp in the country’s serial wars. But an important current that has fed into today’s resurgence of nativism flows from the border, in the steadily growing animus directed at migrants, first from Mexico and then Central America.

One example in particular captures what could be called the nationalization of border brutalism, or the borderfication of national politics. In 1931 Harlon Carter, the Laredo son of a border patrol agent, shot and killed a Mexican American teenager, fifteen-year-old Ramón Casiano, for talking back to him. Carter then followed his father into the patrol, becoming one of its most cruel directors. Presiding over Operation Wetback in the 1950s, Carter transformed the patrol into, as the Los Angeles Times wrote, an “army” committed to an “all-out war to hurl tens of thousands of Mexican wetbacks back into Mexico.” At the same time, border brutality pulsed outward. In the 1960s, intelligence gathering and rapid-response raid techniques worked out in Operation Wetback started to be exported to the third world, to police and military forces who would organize Latin America’s and Southeast Asia’s infamous death squads.

Carter was already a member of the National Rifle Association when he murdered Casiano, and he remained a high-ranking officer with the organization through his years with the border patrol. Then, in 1977, after his retirement from the patrol, he led what observers called an extremist coup against the (relatively) moderate NRA leadership, transforming the organization into a key institution of the New Right, a bastion of individual-rights absolutism. In a remarkable echo of this history, it was a border patrol agent who in 2015 invited Donald Trump to tour Laredo’s port of entry, just a few days after Trump announced his presidential candidacy.

A different kind of western writer, the novelist Cormac McCarthy, had a name for the place where the frontier meets the border. He called it the blood meridian, where endless sky meets endless hate. His novel Blood Meridian (1985) tells of the marauding of a roving gang of borderland scalp-hunters around the time of the Mexican–American War (1846–48). The blood meridian signaled the place where the conceit of progress gave way to an infernal timelessness, to a land “filled with violent children orphaned by war,” where soldiers and settlers got caught in a dervish swirl, powered by demonic rages, moving in circles going nowhere. That place used to be out there, beyond the frontier. But the United States crossed it so many times that the line was erased.

Trumpism is extremism turned inward, all-consuming and self-devouring.

Now, rather than the frontier opening up, the border is closing in. The nation’s archetype is no longer the pioneer. The icons now are the ICE raider and border agent. The log cabin has given way to detention centers where uniformed men and women—or private contractors—lock children in freezing rooms and force drugs on them so they will sleep, even as they deny them medicine. In The Line Becomes a River (2018), his memoir of his time working with the U.S. Border Patrol, Francisco Cantú tells of what he and his coworkers would do when they came across a stash of supplies hidden by migrants: “We slash their bottles and drain their water into the dry earth . . . we dump their backpacks and pile their food and clothes to be crushed and pissed on and stepped over, strewn across the desert and set ablaze.”

Such reports from the borderlands read like pages from Blood Meridian, from a world completely devoid of morality, stripped of the ability (or the need) to justify violence as necessary to bring about progress: “I still have nightmares,” writes Cantú, “visions of them staggering through the desert . . . men lost and wandering without food or water, dying slowly as they look for some road, some village, some way out. In my dreams I seek them out, searching in vain until finally I discover their bodies lying facedown on the ground before me, dead and stinking on the desert floor, human waypoints in a vast and smoldering expansion.”

The brutality piles up: children sexually and psychologically abused; migrants murdered, their murderers immune to prosecution; families teargassed. Where other frontier-theorist presidents, from Woodrow Wilson to Ronald Reagan, waxed lyrical about big skies and open ranges, the current occupant of the White House sings of a different symbol of the West. “Barbed wire,” Trump said, referring to one of the ways the soldiers he deployed to the border were going to keep out asylum seekers, “can be a beautiful sight.”

Why now? What brought about this moral collapse? That is the question for our times. My answer is that Turner’s “gate of escape” has been slammed shut by endless unwinnable wars; deepening political inequality; a venal, arrogant ruling class; and a realization, acknowledged or not, that the natural world is on the verge of collapse. Trumpism is extremism turned inward, all-consuming and self-devouring. It is what comes when the promise of endless growth, and the diverting power of missionary expeditions, can no longer be used to satisfy interests, reconcile contradictions, dilute factions, or redirect anger.

Where the frontier had been imagined as the future, the borderlands stage the past’s eternal return, the place where all of history’s wars become one war. The Minuteman Project, a group of border vigilantes, was founded by a Vietnam vet, just around the time that the Abu Ghraib prison torture story broke in the national press. Many border patrollers and private security contractors have done multiple stints in Iraq and Afghanistan, or in one of the many other countries where the United States is waging its global War on Terror. “For me, it is therapeutic to come down here and join my fellow veterans,” said one member of a border vigilante group, who after four tours in Iraq was left with brain injury and stress disorder. “I miss it,” a private security guard at a border detention center recently confessed to another veteran, a Border Patrol agent. “I’ll see a Black Hawk fly by and think of those days.” “You’ll never get it back,” came the agent’s reply.

The horrors blend into each other, with the closing of the frontier hastening the hallucinatory collapse of historical time. A recent ACLU report documenting the sexual and psychological abuse of migrant children detained by U.S. border agents could have been written in the years after the Mexican–American War, when U.S. soldiers committed acts so heinous they would, according to General Winfield Scott, “make Heaven weep.” Passages from Cantú’s memoir echo Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confession (1950), the memoir of the author’s involvement with an infamous borderland gang that inspired McCarthy’s Blood Meridian.

In any case, the United States stands on the precipice. As the poet Anne Carson writes, “to live past the end of your myth is a perilous thing.”