A number of recent books have put the methods of the social sciences in the service of understanding Trump, his movement, and his enablers, from Russell Muirhead and Nancy Rosenblum’s A Lot of People Are Saying (2019) to Jennifer Mercieca’s Demagogue for President (2020). But it may be equally constructive to examine the older works of social science and theory upon which these new studies, at least implicitly, rest. On this list would be canonical sociological studies such as Max Weber’s Economy and Society (1922) and historical essays such as Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” (1964) as well as the radically interdisciplinary projects undertaken by the researchers and theorists who comprised the Frankfurt School—Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse, and less familiar figures such as Leo Lowenthal and Friedrich Pollock.

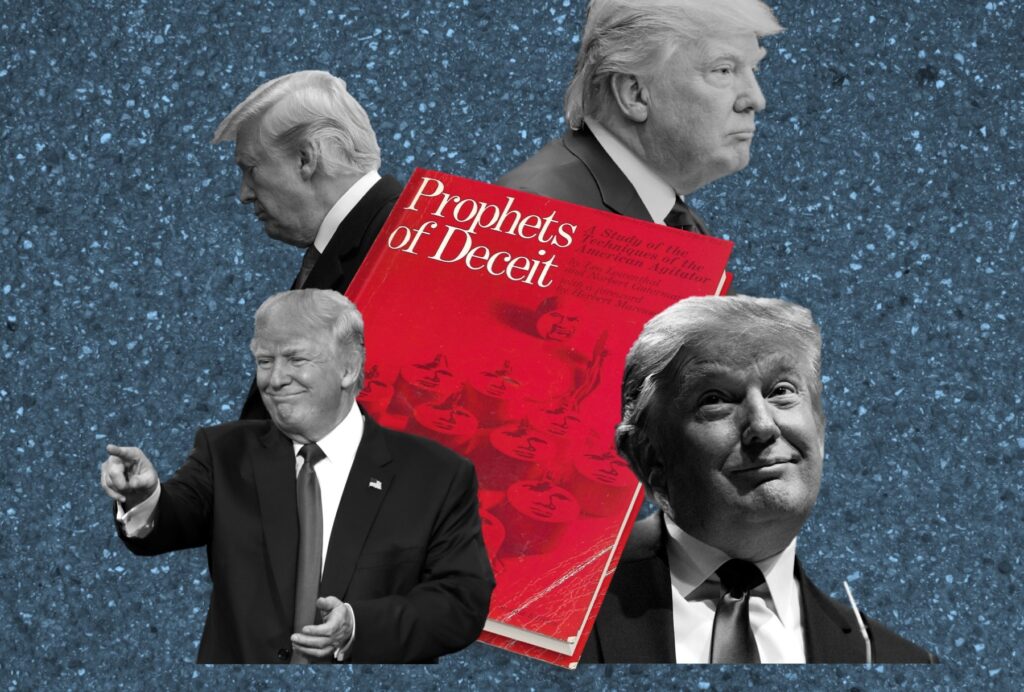

Among the school’s midcentury empirical projects, The Authoritarian Personality (1950), a groundbreaking study of fascism as a psychological phenomenon, had the most impact and remains the most influential. But another, less well-known project, Leo Lowenthal and Norbert Guterman’s Prophets of Deceit: A Study of the Techniques of the American Agitator (1949), offers the most striking insights into Trump and Trumpism. The president and his movement, Lowenthal and Guterman suggest, are the inevitable outcomes of a social, economic, and political order that generates human needs, both material and psychological, that it cannot satisfy. Promising to resolve this “social malaise” even as he reinforces the conditions that generate it, Trump dupes his followers into perpetuating their own misery and preparing them for the totalitarian order he hopes to bring about.

Seventy years later, the book offers a trenchant analysis of our current situation. There can no lasting solution to Trump’s destructive style of politics, the authors suggest, unless we reckon with the conditions that produce it.

Prophets reflects an important but neglected strand of the work of the Frankfurt School. Although best known for its philosophical account of modernity and mass culture, the group was equally committed to the design and execution of empirical research projects.

This work has dropped out of public memory in part because of the dominant historical narrative of the school’s development. During the 1920s and early 1930s in Germany, affiliates of the school pursued a Marxist-aligned research program that combined methods from across the social sciences in order to investigate the economy, society, ideology, and culture of twentieth-century capitalism. In his 1937 programmatic description of this “critical theory,” Horkheimer insisted that the Frankfurt School go beyond mere description and diagnosis to release the potential for justice, freedom, and material security immanent—but repressed—in the social and economic order of the day. From this goal, the Frankfurt School derived standards of rationality and progress. Whatever contributed to emancipation, equity, and well-being was rational and progressive; whatever inhibited it was irrational, regressive, and self-defeating.

These ideas soon came face to face with Nazism, which forced the school’s members to flee for the United States in 1934. According to the typical story, this encounter with U.S. society—including its distinctive form of social science—impelled the group to abandon its interdisciplinary materialism for a theoretical critique of instrumental rationality. But this account misses dozens of empirical studies members of the Frankfurt School conducted during their decade-and-a-half-long exile, many in collaboration with their new American colleagues. Some studies extended lines of inquiry initiated during the Weimar Republic, while others reflected the new political context and intellectual climate. As Horkheimer put it in 1942, the school aimed to combine “highly developed American empirical and quantitative” methods and the “more theoretical European” approach.

Prophets was a product of this interaction. Already in 1936, Horkheimer had argued that earlier demagogues—Girolamo Savonarola, Cola di Rienzo, and Maximilien Robespierre—illuminated the intertwinement of social and psychological forces, exemplified the contradictions of bourgeois morality, and perpetuated irrational modes of domination. During the next decade, Frankfurt School researchers used this approach to study some of the “agitators,” as they called them, whose rallies, radio programs, and propaganda saturated prewar and wartime America with anti-Semitic, anti-Communist, nationalist, and frankly fascist vitriol. By 1944 Lowenthal, Adorno, and Paul Massing had completed three studies—on Joe McWilliams, Martin Luther Thomas, and George Allison Phelps—as well as a methodological essay. According to Lowenthal, the period was one of intense collaboration, especially between himself and Adorno. Adorno explained in 1948 that the forthcoming Prophets was a synthesis of the Frankfurt School’s analysis of the agitator.

Prophets also bears the marks of close collaboration with U.S. institutions and thinkers. Most apparent were the contributions of the American Jewish Committee, the advocacy organization that sponsored much of the Frankfurt School’s research into anti-Semitism in the United States and that published both Prophets and Authoritarian Personality. Less obvious, but no less important, was the influence of American intellectuals—from pragmatist John Dewey and progressive Walter Lippmann to the lesser-known social scientists Harold Lasswell and Robert Lynd—worried by the rise of fascism and the perceived crisis of democratic institutions and political culture. In this sense, Prophets embodied Horkheimer’s proposed interweaving of critical theory and U.S. social science.

Perhaps the most consequential result of this collaboration was the study’s dual methodological approach. The first prong was “content analysis,” a new method for systematically analyzing the creation and transmission of meaning through speech and text. Researchers in the emerging field of communications studies practiced content analysis by assembling a large body of evidence and then parsing each text, cataloging recurring images, tropes, claims, and rhetorical devices. Armed with this evidence, the researchers developed comparative, and, in their view, empirical arguments about the discourse as a whole. Prophets, in particular, applied content analysis to dozens of agitators’ radio addresses, rally speeches, periodicals, and pamphlets, ultimately identifying twenty one recurring themes, from the “charade of doom” and the “corrupt government” to the “simple Americans” and the “bullet-proof martyr.” No matter which agitator was speaking, content analysis showed, the audience always heard the same thing. It was this consistency, this endless repetition, that enabled agitators to gather supporters and build movements.

The second methodological prong was psychoanalytic theory (used by other Frankfurt School members as well). Lowenthal and Guterman drew on the writings of Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson to explain how the agitator’s material activated “unconscious mechanisms” in followers’ minds, reinforcing deep-seated fears, manipulating their behavior, and diminishing their abilities to think and act independently. By combining content analysis and psychoanalysis, Lowenthal and Guterman developed a method that, while “frankly experimental,” explained how agitators transformed their listeners into followers, constructed the specter of an existential enemy, established themselves as leaders, and created a hostile world.

Prophets begins with the following scenario. Picture a New York City bus during rush hour. One passenger complains that she is choking as a result of the pushing and squeezing; “something should be done about it,” she shouts to her fellow commuters. “Yes, it’s terrible,” another passenger responds. “The bus company should assign more busses to this route. If we did something about it, we might get results.” Another rider speaks up with a different message: “This has nothing to do with the bus company. It’s all those foreigners who don’t even speak good English. They should be sent back where they came from.”

Lowenthal and Guterman take this scene as a parable of modern politics. They identified the agitator—almost always male—by his ability to magnify his listeners’ emotional reactions and, consequently, to diminish their rational responses to the problems they faced. On its face, this was a relatively straightforward argument: by vilifying foreigners for not speaking English, the agitator drowned out the reformer; through the spectacle of his rallies, he captured his adherents’ attention and energy; by calling for outrageous policies, he disoriented and exhausted his opponents. “The audience,” Lowenthal and Guterman concluded, “is driven to submit to the agitator’s incessant harangues until it is ready to accept everything he says in order to gain a moment’s rest.”

But the agitator also went beyond distraction and dissimulation. Reformers, Lowenthal and Guterman argued, framed complaints in rational terms and offered a plan of concerted action that would solve the underlying problems. Write to the management of the bus company, they might advise; raise the issue at the next meeting of the city council. Agitators, by contrast, encouraged followers to indulge in unreflective, spontaneous behavior: vilify immigrants; rail against crowded cities; claim that the routes were determined by “special interests.” As rituals of emotional catharsis, these outbursts may well have provided momentary relief, but at a high cost: the problem remained. Whatever energy that could have sustained a project of real reform had been uselessly dissipated. “Under the guise of a protest against the oppressive situation,” Lowenthal and Guterman explained, “the agitator binds his audience to it.” Instead of being dismantled, the conditions that needed to be changed were only reinforced. According to Prophets and in keeping with Horkheimer’s program of critical theory, then, the agitator’s platform was not only normatively objectionable but also inherently irrational. Demanding that foreigners speak English might make some passengers feel better, but it would not make the bus less crowded.

Prophets takes the scene on the bus as just one example of the condition of “social malaise.” Following a line of argumentation being developed by their Frankfurt School colleagues, Lowenthal and Guterman claimed that industrial capitalism and mass society had dissolved the nuclear family, destabilized social institutions, and hollowed out traditional cultures, leaving people feeling anxious, alienated, and resentful. Perhaps as a consequence of their suffering, most individuals were unable to understand that their malaise was symptomatic of real needs—for equality, justice, and well-being—that the current configuration of social and economic forces could not satisfy.

“The agitator gravitates towards malaise like a fly to dung,” Lowenthal and Guterman wrote. Unlike reformers, revolutionaries, and even fascists, the agitator spoke directly to his followers’ malaise, telling them what they already felt within themselves: that they had been humiliated, cheated, and excluded by a system—and its leaders—constructed to keep them downtrodden. Instead of trying to resolve malaise by changing the conditions that gave rise to it, the agitator “grovels in it, he relishes it, he distorts and deepens and exaggerates the malaise to the point where it becomes almost a paranoiac relationship to the external world.” What did the agitator hope to accomplish by stoking malaise? Prophets offered a chilling answer: when the audience had been driven to this “paranoic point,” it was ready to be transformed from democratic citizens into totalitarian subjects.

Every movement requires loyal followers; what set the agitator apart from other charismatic leaders was his ability to gain adherents by demeaning them. According to Lowenthal and Guterman, the economic upheaval created by the Great Depression, New Deal, and wartime mobilization left many Americans with the uneasy sense that they had been cheated out of their share of prosperity. Rather than explain or assuage this feeling, however, agitators magnified it, telling their followers over and over again that they were “suckers” and “saps” who had fallen for the many “hoaxes”—the New Deal, World War II, the Marshall Plan—perpetrated by government bureaucrats, foreigners, Communists, and Jews.

Content analysis showed that this humiliation was a key component of the agitator’s material, but the method could not explain why such an apparently counterintuitive technique worked. Turning to psychoanalysis, Lowenthal and Guterman argued that, even as he labeled them “eternal dupes,” the agitator validated his followers’ self-identification as society’s misunderstood and forgotten. Through this constant refrain, the agitator transformed humiliation into a badge of masochistic honor and perceived alienation into a source of identity. What is more, by reinforcing what his audience already—if unreflectively—believed about themselves, the agitator seemed to offer a kind of cynical honesty: they may be suckers, but at least they know it.

What about those who oppose the agitator? For him and his followers, there are no opponents—only enemies. Lowenthal and Guterman explore this conceit through careful study of the agitator’s ability to create a spiraling series of representations. From specific accusations against suspected communists the agitator turned to vague but emphatic claims that violent revolution was imminent; that communism was the “‘RED THREAD’” tying together journalism, global politics, international business, European courts, and the Catholic Church; and, finally, that communism was nothing but a “‘front’” for still-more-nefarious cabals. The agitator’s accusations became so nonspecific that they merged, enabling him to sermonize against the demonic “Communist Banker” who threatened all freedom-loving Americans. This composite was suited to the agitator’s purpose: by depicting enemies as at once strong and weak, cunning and unintelligent, disguised and identifiable, eternal and doomed, pulling the strings and yet never in power, this image convinced the agitator’s adherents that all who opposed them deserved punishment—and, moreover, that these enemies had it coming.

Over and over again—at rallies, on the radio, and in print—the agitator’s audience took this message in. To some observers, the agitator seemed to cast a spell over his audience, to manipulate them with mass hypnosis. Lowenthal, Guterman, and their Frankfurt School colleagues understood the process differently: their analysis showed that the repetition of images and slogans wore down the listeners’ psychological defenses. Beginning with his first offer of temporary emotional relief from social malaise, the agitator encouraged his listeners to set aside autonomous, logical, evidence-based thought; he invited his followers into the realm of hostility, paranoia, and irrationality. Having undermined rational faculties from within, the agitator proceeded to impose an alternate reality of his own making, a world split by the existential distinction between friend and enemy, survival and death, strength and weakness. Whenever the agitator spoke, his followers heard the same message: “The world is an arena of a grim struggle for survival. You might as well get your share of the gravy.”

In exchange for loyalty and submission, the agitator’s adherents were promised protection, guidance, and, especially, revenge. Soon, he continually assured his followers, government institutions and state power would be turned on the movement’s enemies: foreigners, immigrants, refugees, dissidents, and, especially, Jews. But this promise was only superficially political. At its core, the pledge addressed the malaise of the audience. The agitator never promised his followers direct access to power. Instead, they were to remain perpetual “watchdogs of order,” thrown the bone of witnessing the humiliation, degradation, and persecution of those outside the movement. Although there would be no real change—no resolution the problems behind social malaise—this violence would be “great fun.”

This argument linked Prophets to the Frankfurt School’s best-known work, Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), and especially to the chapter on the psychological meaning of anti-Semitism (to which Lowenthal also contributed). Building on Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents (1930), the authors argued that, from its earliest origins, human society required its members to repress their instinctual drives in order to enable coexistence and, ultimately, to realize higher ends. In modern times, this dynamic had revealed its true pathology as mass society, culture, and politics joined with industrial and consumer capitalism to demand that subjects violently repress the pursuit of individuality, community, and happiness, generating the feeling that Freud termed “discontent” and Lowenthal and Guterman described as malaise.

Examined in this psychoanalytic framework, calls for persecution were part of a dynamic of repression and projection: the agitator exhorted his followers to ascribe everything that they must deny themselves—the development of individuality, the desire for community, and the quest for happiness—to an “other” who became an object of their hatred. These rituals of persecution, stoked by the agitator, vented the excess pressure that would otherwise destabilize the status quo. But, lest the movement collapse in a paroxysm of violence, the agitator must always defer his “call to the hunt”—his performances must be nothing more than a “strip tease without end.”

There is an argument to be made that, like Authoritarian Personality, Prophets used empirical evidence to bolster the psychoanalytic theory developed in Dialectic. For Authoritarian Personality, the evidence came from hundreds of questionnaires, interviews, and calculations provide; in the case of Prophets, it came from systematic content analysis. But despite this similarity, Lowenthal and Guterman’s study moved along a different course from Horkheimer and Adorno’s text. For one thing, Prophets was more concrete than Dialectic. And, in its concreteness, the study was explicitly political. It analyzed contemporary social movements, infamous demagogues, and current events; it spoke about the challenges the United States was facing and about the dangers that it might face in the future. Perhaps the most important manifestation of this political focus was the text’s explanation of the consequences of agitation: according to Lowenthal and Guterman, the agitator was remaking his followers from the inside, preparing American citizens for totalitarianism.

Unlike Hannah Arendt, whose Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) appeared soon after Prophets, Lowenthal and Guterman argued that totalitarianism did not dominate its subjects through cruelty and terror. Instead it made them compliant with psychological manipulation. Overwhelmed by the endless repetition of racist stereotypes, political invective, and violent fantasies, Americans were primed to accept whatever they were told without a moment of hesitation. Taken in by the agitator’s constant patter of self-aggrandizement, victimhood, and accusation, his adherents were trained to support their would-be leader unconditionally. Long exposure to agitation would transform the engaged citizens into pliant subjects.

Making this argument led Lowenthal and Guterman to dissent from Arendt in another important respect: according to Prophets, totalitarianism arose not from the long-term challenges and acute crises faced by European nations but from the basic structure of market economies and democratic states. The needs generated in, but unresolved by, the U.S. economy, society, and culture created the path that led from democracy to totalitarianism. “It is as though,” Lowenthal and Guterman wrote, “the American agitator had evolved a method of directly converting the poisons generated by contemporary society into the quack remedies of totalitarianism.”

One fear that prompted Prophets and other texts in the Frankfurt School’s Studies in Prejudice series was the researchers’ anxiety that, as the political compromises, sense of unity, and economic growth that were integral to U.S. successes during World War II broke down, the nation would enter a period of economic contraction, political fracture, and widespread social malaise. Agitators thrived in such moments. When thousands of demobilized troops returned home, the agitator had the potential to become as successful as he had been at the peak of the Great Depression. (Such troops were a group particularly susceptible to demagoguery, another volume in the Studies in Prejudice series argued.) When Prophets appeared, it seemed that the United States had managed to avoid this worst-possible outcome. The threat posed by agitation was, for the moment, largely hypothetical.

But the threat of agitation remained. Every industrialized, free-market democracy that generated needs it could not satisfy had the potential to become a totalitarian regime: the United States, the other Allies, and all the nations restored or created out of the wreckage of the Third Reich. “The psychological attitudes and social concerns that flow from the crisis of liberal society,” Lowenthal and Guterman explained, “provide a sufficiently fertile soil for the growth of anti-democratic tendencies.” This crisis could be deferred but not overcome. Even a small change in the precarious balance of material, political, and economic conditions might enable the rise of an agitator, a demagogue able to activate the potential for totalitarianism, often unseen and ineradicable, in the nations of the postwar West.

Some seventy years later, Prophets is now diagnosis rather than prognosis. Much of what Trump does and says fits neatly within Lowenthal and Guterman’s analytical framework—from his conspiracy theories of black-clad thugs on planes (a charge that aptly illustrates the agitator’s construction of an enemy that is simultaneously weak and strong, recognizable and unseen) and his ritualistic performance of Oscar Brown Jr.’s song “The Snake” (an example of the agitator’s relentless demonization of immigrants and refugees as an insidious threat to his followers) to his characteristic combination of preening self-aggrandizement and bottomless sense of persecution (a central component of the agitator’s self-representation) and his constant, raucous rallies (events that serve the agitator’s need to keep his followers in a continual emotional frenzy).

And it is not only Trump who exemplifies the arguments of Prophets. Much like the adherents of midcentury agitators Lowenthal and Guterman studied, Trump’s followers have transformed their perception of social and economic marginalization into a kind of identity reinforced by their chosen leader—only instead of “eternal dupes” they are the “silent majority.” On a more structural level, Prophets illuminates the chaotic dysfunction of the Trump administration: the agitator has no real ideology, doctrine, or favored policies; there is only the movement, only “winning.”

The congruence is striking, but the value of Lowenthal and Guterman’s text goes beyond such isolated insights; it lies in its ability to explain, across the intervening decades, both the rise of Trump and the enduring appeal of Trumpism, despite nearly four years of constant crisis. According to the argument of Prophets, Trump keeps followers because he speaks directly to their experience of social malaise. He tells them what they already feel: “The system is rigged; it’s crooked.” And, as Trump put it in at the 2016 RNC, “I alone can fix it.” Trump is correct—there is something deeply wrong—but his fix is an illusion. Even as he demonizes immigrants and minorities, rehearses his cultural and personal grievances, and rails against his perceived enemies, Trump has enacted policies, from deregulating industry and erecting protectionist tariffs to attacking the Affordable Care Act and cutting taxes for the wealthy, that not only do not help but in many cases hurt his most fervent supporters. Like the rabble-rouser on the bus, Trump channels his followers away from rational redress and toward emotional outbursts. In the end, “he tricks his audience into accepting the very situation that produced its malaise.”

It is imperative that we understand this change not only as the lamentable end of an era of bipartisan comity but also as evidence of Trump’s power over his voters’ actions, attitudes, and perception of reality itself. Prophets warns us that Trump will use—is using—this power to prepare his followers for totalitarianism.

At the very heart of Trumpism, Lowenthal and Guterman would argue, stands the threat of violence: the agitator’s constant promise that his followers will visit revenge—in the form of physical harm, political persecution, and social sanction—on those who, they believe, demonized and excluded them. Violence is both the animating principle of Trumpism and one of Trump’s most powerful tools. Trump’s most fervent followers, from QAnon conspiracists to white nationalists, glory in the conviction that arrests of prominent Democrats, purges of pedophiles, and pitched street battles against the left are just around the corner. From his assertion that there were “good people on both sides” at Charlottesville to his order that the Proud Boys “stand back and stand by,” Trump has shown, time and again, that there is no Trumpism without violence. During an October rally in Michigan, Trump casually remarked that there is “something beautiful” about watching protestors get “pushed around” by the National Guard. “You people get it,” he told his loyal followers. “You probably get it better than I do.”

Perhaps the most important lesson to be gotten from reading Prophets in the age of Trump is that he is not an exception to postwar U.S. society but rather its inevitable fulfillment. Trump arose from, and thrives on, needs created by consumer capitalism and mass society—needs not only for a more equitable distribution of wealth but also for dignity, identity, and recognition. Even if Trump loses the coming election, we cannot go back to the way things were before 2016, for it was the normal course of society, economics, and politics that delivered our deeply precarious present. Trumpism will not be defeated until the problems that give rise to malaise are solved, until basic needs are satisfied.

Trump is, in short, America’s agitator-in-chief. His reactionary politics are our creation, and his proto-totalitarianism is our possible future. But Prophets would hardly countenance despair. As Lowenthal and Guterman show, the agitator does not create complaints; he merely redirects them. Through his lies, deception, violence, and spectacle, the agitator distorts what might otherwise be powerful forces for change; instead he induces his followers to work against their interests. But the possibility of change remains. Prophets of Deceit protects this hope, even as it shows us the difficulty of realizing it—and the stakes of failing to do so.