August Kleinzahler seems like the last poet who would try to explain himself in public terms. He has been so much a poet of elapsing moments and sudden access to feelings and sensations, that reflecting on his own processes could only defeat, rather than clarify, his purposes. But in this new book, his second with a commercial publisher after a long foreground of small presses, we are intrigued to find many of the poems concerned with their own natures. That Kleinazhler has dramatized this concern in a way that engages the reader intensely is one measure of the book's success.

This book is dedicated to the British poet Thom Gunn, and the two poets' respective careers make an instructive comparison. Gunn's early work snickered with its own incongruities as he depicted biker bars and Elvis Presley's final days in precious, complex forms. But his later poems manage to be streetwise without being so smart-ass. Their technical skill gives them poise as much as polish, and the poet uses this to lend dignity to the desperate souls he writes about.

Kleinzahler's progress has been somewhat the opposite. He has never been merely crude or raunchy, although these qualities abound in his poems. Like early Gunn, he mixes the high and low for comic effect, but with the important difference that he also reveals how well, even subtly, they complement each other. Kleinzahler can compare a drunk, sitting on the sidewalk and hacking phlegm until the effort makes him vomit, to a chivalrous knight jousting in the lists, so that the analogy seems natural, perfectly toward. That, in spite of the incongruity, is what makes you laugh. Gunn had to develop this sense of balance. For whatever reason, Kleinzahler has never been saddled with the either/or conflicts that Gunn had to unlearn, or learn to live with. He has felt free to ventriloquize, perfectly, cabbies and bartenders; to see the world through the eyes of loitering cats; or simply to sketch the weather, which for him is the complexion of life.

But in his new work, Kleinzahler is less comfortable with his freedom. He steps back to consider his relation to the given. There are fewer street folk in Green Sees Things in Waves, and more artists looking at streets, although it's hard ever to claim certainty about Kleinzahler's point of view. The "Green" of the title poem, for instance, turns out to be a character, not a color. Green is someone whose doors of perception have been warped by LSD, and who now sees waves where the rest of us detect stable matter. The title then turns out to be a statement of pathological fact, rather than playful nonsense. Yet the trick it plays on the reader's perception, coupled with the poem's composition in an un-stopped, wave-like syntax, suggests that Green's distorted vision is close to the poet's.

Kleinzahler's poems often simply stage a process in which sense turns into nonsense and back again, depending on how we use our senses, or perceive a word. Just as often, in this book, that process is caught and released, so we can examine, and not only experience, its workings. In "Silver Gelatin," we stand with a photographer on the fourteenth floor above a park, preparing to ambush life when it strays into "an hour, an afternoon light / well along into winter" that he has chosen for background. When "a solitary young domestic" pushes a pram into view, not sitting for a portrait but literally stepping into the frame, he sees what he has been looking for: the angle she makes "could not be improved upon." But since this is life, not art, he is taking a picture of, her perfect composure doesn't last. In pushing through the terrible cold to get "the baby home for dinner," she assumes an "extreme angle." This upsets his plans at first, but in the end life finds the form that fits it best, and the photographer is pleased with the result:

she looks, for all the world, from here,

a broken off piece of Chinese ideogram

moving across the page.

The comparative "like" that would make the analogy explicit is missing, because seeing and likening have become the same act. Life and form both have a hand in creation, if not first without some disagreement. The domestic's physical difficulties broke the photographer's concentration, but they forced him to recognize a new, more striking form. It was his trained eye that recovered an even better picture than he had preconceived.

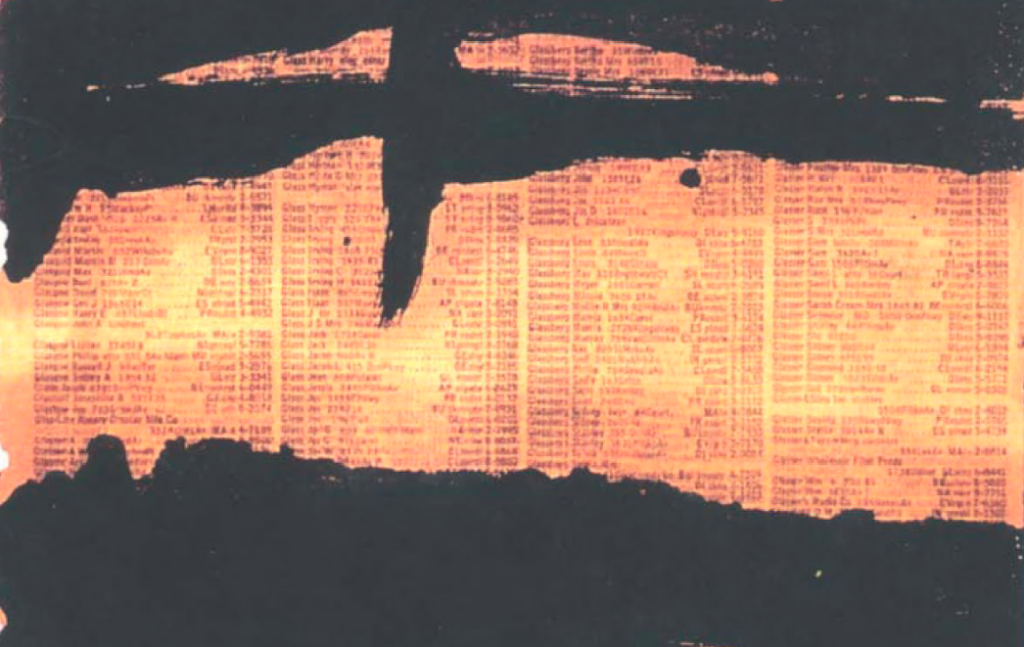

The title takes us back to an era when photographers were forced, by the limitations of their equipment, to take pains in choosing and composing their subjects. Photographers worked faster than painters, but taking and developing pictures was still much slower than the snapshot technology of today. The photography of that era, as practised by someone like Stieglitz, provides Kleinzahler with his model of an art that captures life while it happens, but also reminds us there is someone around and behind the lens, choosing and arranging the shots. The ideogram is likewise poised between high modernist and contemporary interpretations of that form of writing. It condenses, as Pound taught, capturing "all the world" in a finite shape. But it is also partial in itself, and active, communicating just the movement to which it lends an edge, as on Franz Kline's canvases. (One of Kline's studies, black daubs on a page from a phone book, adorns the cover of this book.)

Kleinzahler's poems have always performed both these functions, but only in new work, like "Silver Gelatin," has he drawn that fact out for emphasis and consideration. In "Poem," from the earlier book Like Cities, Like Storms, he described orgasmic shudders with an analogy-"She's flipping like a marlin / in lamplight"-then in terms of negative space around the body:

the air above her

thrashed to a foamthat eddies awhile

and then drifts down to crackle

and glow on her belly.

The first device is verbally, the second physically, remote from her body, yet the focus on sensation seems seamless. Only a second look acknowledges that the focus is composed by distant and distancing elements. By exploiting this insight, Kleinzahler's new poems cease to appear as pure, elapsing content, and beg to be considered in terms of their boundaries and limits. By showing us the photographer at work behind the camera, the poet exposes his role in framing the final image. "Silver Gelatin" coincides with the picture the photographer takes, but it is also a picture of the photographer, and clearly there are things about him we must judge. These include his already mentioned disappointment, when the domestic's suffering disrupts his aesthetic preconceptions. That is selfish, to say the least. Also, the deliberate choice of time and setting, which is passed off to the viewer as the immediate response, perhaps of a flaneur. The photographer isn't wandering about the city, but perched like a vulture on a cliff.

As if to illustrate this last point, another poem in the book, "Vulture Under the Palisades," describes the "narrow russet instrument of face" that one of these creatures, waiting high above the river, possesses. Combining the organic and mechanical in its features, it must be what the photographer, looking through his lens, looks like from the domestic's point of view. The vulture wasn't interested in Kleinzahler because he was still alive. To the photographer, only interested in cold form, the domestic and the baby may as well be dead meat. The poet's artlessness is partially contrived, and his appetite for life turns out to have a disturbing bestial element. These duplicities are put on trial in "The Dead Canary," where the poet is accused of transgressions that only resemble his real crimes. When he and an old lady both come across a dead canary on the sidewalk, the old lady suggests a conspiracy behind the corpse. "Someone's poisoning them," she says, then flashes the poet "an eldritch look." The accusation is as daffy as her paranoia, but the poet still feels defensive:

As if I spent my days with a dropper,

skulking about in search of their feeders,alive only to cancel out their color and song.

This defense goes on for several more lines, until we think the poet has protested too much. Not because he really is some kind of murderous taxidermist but because, as a poet, he murders to dissect. He protests he is "not a beast, but a clement soul," who can "fill with pity" at the bird's "ruined wings." But then he also marvels "at what a picture it makes,"

nicely off-center and ravaged enough

but not too, spread out there

on a square of sidewalk-framed:

The poet is unfairly framed by the old lady-he isn't out thrill-killing pets-but he is guilty of framing the bird's tragedy as a pretty picture. On the other hand if art preys on life, even kills it by framing it, the poet feels justified in his criminality because his admiration for the canary's rumpled form also preserves it, if only momentarily, from the ravages of life. The latter are represented by examples of real animal hunger that provide the poem's ultimate frame: at the beginning, the old lady has to give "her black Scottie / a yank before he inhales the remains"; in the last lines, the poet knows that the bird will only look like this until "a cat comes along to tear it apart / or it's sluiced to the gutter by rain." That these appetites are indifferent to beauty makes their indifference to life truly spiteful and pathetic. Between them, the poet confesses to his own "beast savor," as he calls it in another poem, but mingles this with purely human remorse.