“I’ve never understood why mindfulness couldn’t be constituted by a brimming-full mind,” writes Matt Donovan in his new book of essays, A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape, and this book brims indeed. In one essay, Donovan leaps from Bashō to First Lady Helen Taft to shipwrecked Aeneas to the bombing of Hiroshima, all while detailing the peculiarities of the history of Washington, D.C.’s famous cherry trees. In another he chronicles how a minimalist sculpture of a halved pillow on a blue pedestal, constructed by a friend with cancer, calls to mind the bust in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” and its famous last line, “You must change your life.” Donovan’s mind moves like a Tesla coil, riding the energetic frequencies between polarities and points of experience: the book is a compendium of synaptic flairs.

The overarching concern of A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape is how we contend with ruin. Its central locales are Pompeii, the Pantheon, and anywhere scarred by the birth of the atom bomb. For Donovan, the past too is a place: time and memory offer historical and personal topographies to survey. The book commits great acts of ekphrasis: Pompeiian frescoes, the paintings of Raphael, Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field, and all manner of kitschy Americana are but some of the objects that help Donovan think. Just as often, Donovan thinks about what cannot be seen, from radioactivity to God, and explores the value of mystery and uncertainty. And for all the backward gazing of these essays, it can feel, reading them, as though the past were speaking to us now about our anxieties about the future. In this way, A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape is a very timely book.

—Dana Levin

Dana Levin: This is your first book of essays, after doing time (ha!) as a poet. What led you to the essay form, and how is working with it different from writing poems?

Matt Donovan: There was a very specific moment that lured me toward the essay form. Years ago, at a time when I was only writing poetry, I felt compelled to tackle the subject of the Trinity Site in New Mexico where they tested the first nuclear bomb. I did a bit of research, found my odd little foothold in the topic, and wrote a hot, unresolved mess of a poem. Not long after writing it, though, I visited the Trinity Site during one of its biannual open houses, and after a truly visceral response to experiencing that disturbing place, found myself loaded with new facts and strangeness that I desperately wanted to write about. Suddenly, honing the poetic line and privileging compression interested me far less than trying to interrogate that intersection of history and personal experience. I don’t mean, of course, that poems can’t enact those same strategies as well, but for me as a writer, the essay provided me a more immediate and direct means of addressing that place. Even if I ultimately wanted to forge metaphor and explore motifs and hone my language just as I would in a poem, I also felt the need to deliver some fairly complex history, or even basic terms and facts, which I didn’t want to risk obfuscating.

Daily life in the Internet age makes us constantly careen between the sacred and profane, the ridiculous and sublime.

DL: I wanted to ask about the relationship between art and empathy, a relationship the book explores in numerous essays: In “Garden of the Fugitives,” you meditate on the plaster casts at Pompeii, casts of those killed in the explosion of Mount Vesuvius, saying, “Any lurch toward empathy was consistently derailed by an interest in process and form.” In “House of the Tragic Poet,” you write, “A site of devastation becomes a spot for someone like me to parse through ruin, looking for things rich and strange.” Can you talk about how making and appreciating art keeps empathy at bay? Can art also be a vehicle for empathy?

MD: In writing the essays in the collection, I found myself preoccupied with the complexities of any empathetic response. I wanted to investigate the extent to which empathy is possible, and the myriad ways in which the self and even artistic craft might muddle it. I felt emotionally overwhelmed after my visit to the Trinity Site—one of the twentieth century’s many hubs of atrocity—and yet eventually hopped in the car and drove away. As it happened, I had to head directly to a friend’s wedding reception, which was truly disorienting and afforded an occasion to chase down this theme in the piece. Meanwhile, in those essays about Pompeii, I wanted to explore our ability to sustain an emotional remove from the tragedies we are confronted with. When I encountered those famous plaster body casts, I found myself occasionally blindsided by something resembling grief—and some of those figures have been deliberately arranged in order to have an emotional impact on the viewer—but more frequently felt myself merely intrigued by what I was looking at. I wanted to know how the forms had been made, and I could already feel metaphors tugging at my sleeve. And, of course, I wanted to hone my language. Wordsworth famously defined poetry as emotion recollected in tranquility, but I am interested in the ways craft, in the midst of all that quiet, can potentially dilute that incipient emotive response as we go about shaping our syntax, culling our words, and racing after some chosen motif.

Pompeii / Photograph: Matt Donovan

DL: I love the way the book seamlessly mixes the sacred and the profane, the classical and the kitschy. You seem to have an impulse to bring the lofty down to earth, as in the essay “Dew Point,” where you keep calling Masaccio “Sloppy Tom” (telling us this is what “Masaccio” means), or your essay on the Pantheon where you describe Rome as a city in “infinite shades of Tang.” What drives this impulse?

MD: I have a couple of thoughts on that. First, it seems as if daily life in the Internet age makes us constantly careen between the sacred and profane, the ridiculous and sublime. Here is a photograph of a refugee boy drowned on a beach, and, with a click, here is an animated GIF of a pug on a sled. Looking through the postcards at the Pompeii souvenir shops, I saw images of plaster casts of whole families who must have asphyxiated in the volcanic ash and then, with a turn of the rack, flipped through erotic statues and frescoes excavated from the homes. Meanwhile, I talk to my writing students quite a bit about the importance of incorporating their own idiosyncratic lenses on the world into their writing. Writers can potentially find a lovely distillation of accuracy and originality by not shying away from an association that only one’s wacky own self might make. There is a fabulous essay by David Gessner, “Sick of Nature,” in which he beautifully eschews the conventions of nature writing by describing a heron’s “funky seventies TV pimp strut.” Besides, who wants to truck with untouchable grandeur?

Most artists and writers are more at ease tackling the tragic than trying to wrangle with some personal happiness or fulfillment.

DL: I sensed a self-portrait in the moment in “No Fuller On Earth” where you talk about what x-rays have revealed about Raphael’s Transfiguration: his “struggle with the painting’s composition didn’t take place within the darkened lower half where the crowd gathers. . . . Instead, all his reworking and uncertainty took place in the realm of light.” The whole book seems written by someone both drawn toward and skeptical about the spiritual, the religious, the transcendent. Can you talk about this?

MD: I love this question. I definitely thought about that line in terms of the book’s themes, but hadn’t considered it as autobiography. First, I am guessing that the majority of artists and writers would find themselves—for better or worse—more at ease tackling the tragic than trying to wrangle with some personal happiness or fulfillment. I would argue that this is similar for readers, too. Many of us get increasingly restless with The Divine Comedy as we ascend toward the grace and weird choreographies of Paradise, decidedly preferring the smoke and spears of Hell. But to speak to the question of self-portrait, I was raised Lutheran, and even if I fell from faith in my early teens, I know that my early church-going shaped my frames of reference and who I am. No matter my skepticism or entrenched agnosticism, I am still fascinated by the biblical stories that were hammered into me as a kid, as well as the rituals of faith and our desire to believe.

DL: This seems related to a moment where you write, “Who knew our salvation lay in obfuscation, in not knowing, in the dazzling out of reach?” How does not knowing become a vehicle of salvation?

MD: That is actually a concrete example of appropriating one of the Christian tropes that I was raised with, since the larger context of the line you mention is from a riff on the Tower of Babel. That essay is specifically about the Pantheon—."nd [then] race after…ax and culling our words,"too much.n a list of otherwise literal specificity.cal, and natural ecosystema building I became fairly obsessed with during a year that I lived in Rome—and ."nd [then] race after…ax and culling our words,"too much.n a list of otherwise literal specificity.cal, and natural ecosystem."nd [then] race after…ax and culling our words,"too much.n a list of otherwise literal specificity.cal, and natural ecosystemI found myself riding a little eddy of correspondence between the two buildings, both mythical in their own way. When I went back to look at Genesis, though, I found something potentially different from the retaliatory vengeance I remembered from my Sunday-school classes. Just before he destroys the tower, God says, “Now nothing will be restrained from them,” which I took pleasure in interpreting as a gesture of concern about the curse of omniscience. What would the human condition be without our guesswork and fumbling wonder? One of my favorite lines from Shakespeare—and maybe the only text I have ever personally considered for a tattoo—comes from Touchstone in As You Like It. Toward the end of the play, in the midst of all of that beautiful confusion and absurdity, he mock-sermonizes against any codification of beliefs, claiming there is “much virtue in If.”

DL: Last question: I hear you are working on an opera! Tell us about it.

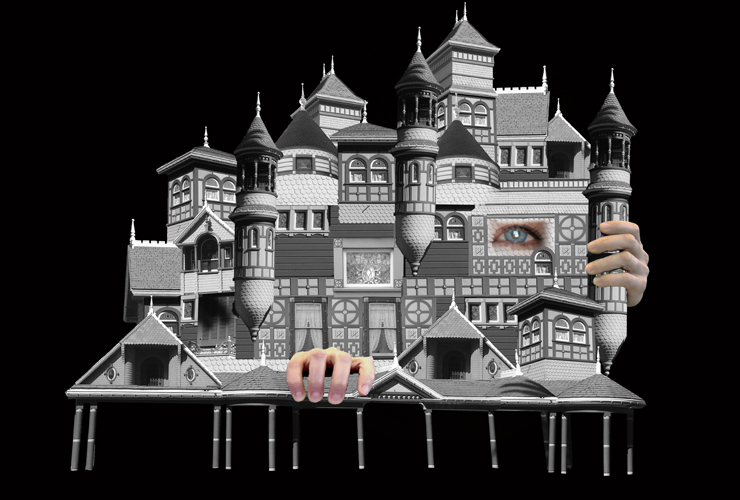

MD: Yes, I am incredibly excited about the project. For the last year, I have been working with a collaborative team on a chamber opera called Inheritance that is based on the life of Sarah Winchester. Although her name might not be immediately recognizable, many people have heard of her home. In brief, she inherited a fortune from the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and, according to legend, was advised by a Boston psychic to move west and to build a home that needed to be kept under constant construction in order to keep the spirits of the dead at bay. I had long wanted to do something that would address the subject of guns in this country, and the legends linked to Winchester afforded an immediate metaphor for many of us in contemporary America: here is someone who inherited a staggering amount of weapons, and who responded to feelings of complicity and guilt by constructing a maze-like home with no conceivable resolution. Writing the libretto has afforded me a re-entrance into poetry, so in a sense I am back serving my time. The work will premiere in 2018, and I am thrilled to be collaborating with artist Ligia Bouton, composer Lei Liang, and soprano Susan Narucki—a wildly talented team!