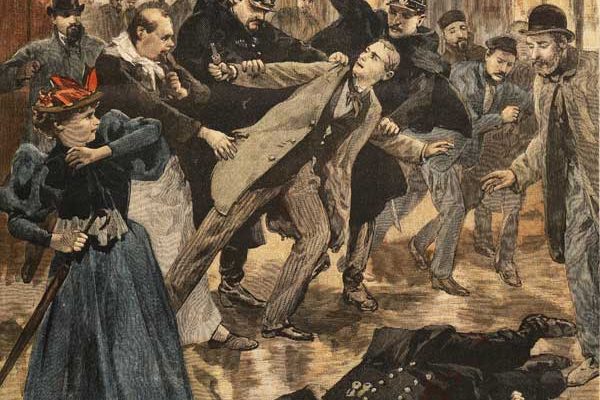

On October 2, 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech warning of the rising threat of “Islamist separatism.” This radical political project, Macron contended, is testing the resilience of the secular French Republic and menacing “freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, and the right to blasphemy.” Two weeks later Samuel Paty, a French instructor who had shown the 2012 Charlie Hebdo cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad to his middle school students in a class on freedom of expression, was murdered by Abdullakh Anzorov, an eighteen-year-old Chechnyan Muslim refugee.

Whereas laïcité once served as a legal principle guaranteeing freedom of worship, it has become a hegemonic cultural norm mobilized against religious minorities in the service of an exclusionary political agenda.

In the wake of Samuel Paty’s murder, the French government proposed a “draft law to strengthen republican values” aimed at reinforcing the principles of French laïcité. Laïcité, often translated as secularism, refers to the French Law of 1905 on the Separation of Churches and State which legally established state secularism. Article 1 ensured liberty of conscience and guaranteed the free exercise of religion, while Article 2 acknowledged that the Republic would not recognize, remunerate, or subsidize any religious denomination. These articles put an end to government funding of religious associations and the government’s ability to name French archbishops and bishops. At the same time, the law declared that all religious buildings were the property of the state and were to be made available to religious associations free of charge. A complex process of negotiation and partial reconciliation between the Catholic Church and the French state followed, continuing on throughout the twentieth century. Today many question the extent to which this historic legal settlement and cultural tradition is equipped to accommodate minority religions and meet the needs of an increasingly diverse society. Yet President Macron has advanced a law against “separatism” to defend laïcité, describing Islam as a religion “that is in crisis.”

The proposed legislation passed the French National Assembly last month and is being debated in the Senate this March. Containing fifty-one articles, it is an aggressive defense of one particular understanding of laïcité and the republican values that anchor the French national project. In the understanding that it advances, laïcité is seen as the key solution to the challenges of vivre ensemble (living together). Its proponents believe vivre ensemble is currently under siege by immigrants (especially those of Muslim background), certain rigorous forms of religious practice, and an unwelcome contingent of “woke” academics and activists who insist on importing concerns about race and politics from other national contexts. If passed, the legislation will monitor international funding for French mosques, restrict online hate speech, and increase the monitoring by the state of the activities and public accountability of religious associations. In parallel, and in close relation to this legislative discussion, the French government has called for curbs on foreign imams in France and pressed the French Council of Muslim Religion (CFCM, Conseil Français du Culte Musulman) to elaborate a “Charter of Principles for Islam of France (Islam de France).” These advances demand a clear demonstration of loyalty to the French Republic in the traumatic context following Paty’s murder. The charter has been severely criticized by French Muslims who question the CFCM’s representativeness and worry about this new attempt at formatting their religious practice in a top down and centralized way.

This is part of a larger government attempt to cultivate and design a reformed “French Islam” that aligns with one interpretation of laïcité specifically, and republican values more broadly. Civil and human rights organizations have expressed alarm over how the proposed legislation would impact public and individual freedoms. A significant majority of the French Muslim population, as well, interpret it as an instrument to monitor and potentially restrict Muslims’ rights in line with the objectives of the War on Terror. In this charged context, the French Ministry of the Interior called to disband the Collectif Contre l’Islamophobie en France (CCIF), an organization dedicated to defending the civil rights of Muslims, in November 2020. The ministerial decree for the CCIF’s dissolution accused the organization of cultivating links with Islamist and radical thinkers and spreading fear among French Muslims in the name of the fight against Islamophobia.

Article 4 of the proposed legislation, which creates a new type of offense for individuals threatening or assaulting an elected official or public sector employee, has also raised eyebrows among free speech proponents. Prima facie, punishing the use of violence against elected officials or public sector employees seems reasonable. However, that this provision is included in this particular package of legislation raises concerns that prosecutors will use it selectively to target claims for exemptions based on religious freedom and more broadly any form of legitimate dissent that is framed as a threat to the Republic.

The move to legally protect a right to blasphemy refuses the right to critically interrogate laïcité itself.

For the past thirty years at least, controversy over Islam in France has returned every year with the predictable regularity of the seasonal flu. Public disputes about the veil, the burqa, the burkini, halal food, and, now, separatism have transformed laïcité. Whereas it once served as a legal principle guaranteeing freedom of worship in the context of a historically Catholic majoritarianism, it has become a hegemonic cultural norm mobilized against religious minorities in the service of an exclusionary political agenda.

In the wake of Paty’s murder, many commentators and politicians have advocated the right to blasphemy and encouraged the brandishing of the Charlie Hebdo caricatures. Yet paradoxically the move to legally protect a right to blasphemy refuses the right to critically interrogate laïcité itself. Proponents of the right to blasphemy understand this right as a part of laïcité. In so doing they situate laïcité above the fray and exempt it from the very critique that they allegedly seek to protect.

In contemporary France the defense of laïcité has come to serve as a litmus test for discerning who is loyal to the Republic and who is a heretic. Leading sociologists, such as Eric Fassin, have been subject to death threats and threats of violence for writing critically about certain aspects of the French politics of countering violent extremism. Two right-wing deputies have called for an investigation into academic social scientists as part of an advance to pass a law that would criminalize what they describe as “ideological deviance.” Historian Christelle Rabier, one of the scholars targeted by a tweet from right-wing deputy Julien Aubert (Les Républicains) attempting to disqualify her as an Islamo-leftist, has pressed charges for “public insult” (injure publique).

In contemporary France postcolonial studies, race and ethnic studies, and gender studies are grouped together in an ill-defined manner and roundly dismissed as a threat to republicanism.

This echoes a broader trend in certain conservative circles of the French intellectual establishment to bemoan the nefarious influence of postcolonial studies, race and ethnic studies, and gender studies. These fields are grouped together in an ill-defined manner and roundly dismissed as a threat to republicanism. The increasing influence of these fields in French academia, the argument goes, is a sign of the toxic infiltration of U.S. theories of race. Transplanted to the otherwise “color-blind” French context, these approaches supposedly sow division and threaten the unity of the Republic. Washington Post correspondent James McAuley and New York Times correspondent Ben Smith have been virulently attacked by adherents of these views for encouraging such allegedly seditious misrepresentations of France’s treatment of minorities in their coverage of the separatism debate. All of these attacks transform republicanism—a French political ideal placing the general interest of the res publica above the private interests of sub-groups and individuals—into a form of ritualist puritanism. This narrow understanding of national community functions primarily as a means of excluding and disciplining actions and thoughts that are deemed deviant.

Last week Minister of Higher Education Frédérique Vidal entered the fray with a vitriolic attack against academia when she announced a plan for the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) to investigate the damage caused by “Islamo-leftism” in French universities. “Islamo-leftism” is a nebulous category that conservative intellectuals and politicians from the left and the right have promoted over the past decade. The category is used to describe an alleged coalition between leftist academics and Islamists, the former acting as the spokespeople for the latter through writings that contextualize the development of illiberal discourse and violence against the French republic. According to Vidal, the CNRS investigation is intended to differentiate between research and activism. Her statement launched a massive wave of critique and condemnation from university presidents, student unions, academic associations, and CNRS itself, all of whom decried the plan as a dangerous infringement on academic freedom that amounts to little more than a witch-hunt. CNRS published a communiqué that unequivocally rejected the notion of “Islamo-leftism” as an unscientific category that has served as an instrument for politicians to regulate social scientific research on Islam. On February 20 Le Monde published a petition signed by 600 scholars, a great majority from CNRS, calling for the minister’s resignation.

Recourse to laïcité evokes a series of contentious debates about what it means to be French. Among them are long-simmering concerns about how assimilation, race, and religion function within the republican project and its varied colonial expressions at home and abroad. Contemporary republican defenders of laïcité have re-dedicated themselves to a series of quixotic efforts to insulate the history, law, and politics of secularism from public debate and discussion, often nodding to the foreign and allegedly divisive influence of a U.S. multiculturalist politics of race. This premature silencing relegates racism, religion, and colonialism beyond the bounds of legitimate public debate. But these concerns demand public discussion.

Contemporary republican defenders of laïcité often nod to the foreign and allegedly divisive influence of a U.S. multiculturalist politics of race.

French protestors have taken to the streets in recent weeks and months to draw attention to the discrimination Muslims face and the sidelining of debate over the role of anti-Muslim racism in both colonial and contemporary France. Many scholars in France and abroad stand with the protestors. To shut down discussions of race, religion, and the limits of free speech in the supposed name of “free speech” and the fight against terrorism is, as Mira Kamdar and Nadia Fadil have suggested, profoundly anti-democratic. The criminalization of allegedly suspect populations who are often at the forefront of such debates perpetuates an atmosphere of suspicion toward immigrants and foreigners more generally. For example, one aspect of the proposed legislation places restrictions on homeschooling and specifies that teaching must take place in French. This flagrantly displays France’s xenophobic tendency, even as proponents of the legislation insist that Muslim French individuals are not outsiders or foreigners, but French citizens.

Critics of the legislation believe that extreme acts of violence by French jihadists, such as Paty’s murder, should be addressed through a combination of complementary methods that operate at different levels and in different temporalities. Only through the combined efforts of educators, social workers, intelligence officers, religious leaders, and community associations can violence in certain segments of the French populace be understood and curtailed. Equal access to education, jobs, and opportunities for advancement and flourishing in French society is of central concern. Those who critique the legislation are well aware of the complexity of prevention and deterrence, as well as the urgency of formulating effective responses in a moment haunted by traumatic memories of the Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan, and Conflans attacks. In their eyes the proposed legislation not only fails as a means of preventing extreme violence, but also promises to further alienate and stigmatize French Muslims who reject violent extremism.

The anti-separatism law focuses on reforming potentially violent Muslims by disarticulating suspect individuals and groups from the broader social, economic, and political contexts in which they are embedded.

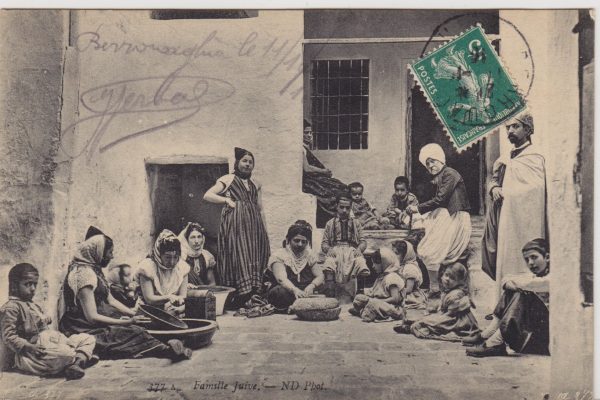

Though laïcité is often considered in the more limited scope of French domestic politics, it has a historical relationship with France’s colonial projects that is fraught with ambivalence. One way to counter attempts to censor debate today is to foreground this complex politics of Islam and secularism in French colonial history. A strong political commitment to laïcité emerged in late nineteenth-century France as part of an assemblage of modernizing developments. While the Law of 1905 was celebrated at home for emancipating French citizens from the authoritarianism of religious institutions, the law was received and wielded quite differently amid the emancipatory politics of North African protectorates and colonies. Scholars such as Raberh Achi, Oissila Saaidia, Mohamed Amer Meziane, and Todd Shepard have discussed how the French colonial regime in North Africa managed religious categorizations and citizenship rights to advance the imperial project of conquest, and to divide and rule. The extent to which the 1905 law had any positive or emancipatory impact on Muslim citizens in the colonies is deeply contested.

Domestic debates over laïcité have never been fully separable from France’s colonial and postcolonial condition; today France continues a legacy of invoking laïcité to claim moral supremacy in contemporary global politics. Of significance is the proposed legislation’s relationship to the Global War on Terror (GWOT); the reinforcement of republican principles; and the call for a militarized form of secularism. The GWOT framework leads to a myopic focus on counterterrorism which, as Bruno Charbonneau and others have shown in their studies of French interventions in Mali, obscures the local forms of political authority and legitimacy that so-called “terrorists” often draw upon. As Charbonneau explains, “the ‘terrorist’ label disarticulates these groups, movements, and dynamics from the contexts of their historical and contemporary relations.” Like the GWOT, the anti-separatism law focuses on reforming potentially violent Muslims in part by disarticulating suspect individuals and groups from the broader social, economic, and political contexts in which they are embedded.

The separatism debate is also occurring in the wake of a major French report on the war in Algeria and the memory of colonization. This report, commissioned by the president of the Republic and written by historian Benjamin Stora, offers analyses and recommendations to better understand the history between France and Algeria. It has been widely criticized by Algerian historians and politicians as an unwelcome unilateral French effort to enunciate the terms of political reconciliation without engaging in the difficult bilateral and reciprocal work demanded by France’s colonial history. The report should have included a more substantive acknowledgement of the violence of French colonialism in Algeria. As Ariella Azoulay recently expressed in these pages in a powerful critique of the imperial erasure of the history of Algerian Jews, the report effectively endorses the outcome of imperial violence as progress. Nabila Ramdani writes in Foreign Policy that the “toothless Stora report feigns an interest in justice while whitewashing colonial crimes.” Elsewhere, Noureddine Amara suggests that Stora “puts the (re)making of a nation before historical work.”

In discussions about separatism, as in discussions of the Algerian war, unity is dictated from above at the expense of plurality, reciprocity, and equality.

In discussions about separatism, as in discussions of the Algerian war, unity is dictated from above at the expense of plurality, reciprocity, and equality. The contemporaneity of the Stora report and the “separatism” debate illustrates the pitfalls of Macron’s ideology of “neither right nor left.” While the bill regarding republican principles was meant to reassure right-wing voters, the Stora report’s attempt at articulating the terms of a reconciliation with colonial memory was meant as a peace offering to the left. But the shortcomings of the report have instead confirmed the government’s attempt to impose a consensus around issues of migration, Islam, and colonialism. The purportedly centrist rhetoric of “neither right nor left” increasingly appears to serve a policy agenda in tune with the right.

It is in this charged context that the defense of laïcité has become akin to a form of religious orthodoxy for supporters of the separatism bill and the “Islamo-leftism” investigation. Choosing the phrase “right to blasphemy” to describe the defense of the right to offend Muslims’ sensitivities and test their potential for successful integration in French society speaks volumes. In a country as laïc as France thinks itself to be, it is odd to introduce into the public sphere the language of “blasphemy,” a notion belonging to religious normativity. Strictly speaking there can be no such thing as “blasphemy” within the terms of secular public order; there is only free speech that may be regulated depending on its potential to disturb public order. In a secular republic, what standard determines what is or is not blasphemous? This phrase indicates a theologico-political use of the notion of laïcité. Acknowledging this shift and contending with the processes through which laïcité has been transformed from a legal principle to a set of norms used to discipline dissent is not, however, to justify violence. The recent claim by staunch defenders of laïcité that the social sciences in France are complicit in violence through their work of historical and sociological contextualization (“expliquer c’est excuser”) exemplifies how dissent is turned into heresy.

In a secular republic, what standard determines what is or is not blasphemous? The defense of laïcité has become akin to a form of religious orthodoxy for supporters of the separatism bill.

The uses of laïcité in France today point to a form of the “illiberal religification of law,” to use a phrase crafted by religious studies scholar Spencer Dew. With this concept Dew shows how some religious communities have come to use “the legal system as a potential tool against the state.” The legal system in such cases becomes a means of transcending the state. Ironically, in the French context, it is the politicians advocating for stricter legislation around laïcité who seem to be turning law into religion, in an illiberal move that places a reformulated laïcité above the state and politics. In the process they confer upon it a sacred status.

On February 1 Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin suggested on radio that “we can’t talk with people who refuse to write on a paper that the law of the Republic is superior to the law of God.” As Olivier Roy notes, this kind of controversial claim expresses a “surprising ignorance of what religion is and of the place of religion in relation to the state. No believer can say that the law of the Republic is superior to the law of God.” The minister’s statement perfectly embodies the move toward the illiberal religification of law. Laïcité calls into legal presence an ambiguous form of extra-state authority that stands apart from the sovereign. Its power lies precisely in this ambivalent relation to the state, in which it both embodies and exceeds state authority.

The French government has been fixated with the task of reforming Islamic theology and training imams since the late 1980s, indicating this double movement from politics to law and from law to sovereignty. Proponents of the new bill to reinforce republicanism seem to see Islam as a threatening rival legal order. This perception draws sustenance from a long history. As scholars such as Iza Hussin have shown, there has been a continuous (re)-invention of Islamic law as a specific kind of “problem-space” for the modern state.

Finally, contemporary attempts to elevate laïcité above politics and history express the political elite’s increasing distrust of French society. In recent years grassroots mobilization against anti-Black racism, police violence, and suppressed civil liberties has proliferated in France and around the globe. These protests represent a formidable force of nonviolent politics from below as a counter force to the global rise of populism and nationalism. And yet the French authorities often understand this international solidarity and cross-national learning as a product of foreign importation. The exasperation expressed by French racial and religious minorities—due to racism, economic inequality, and segregated neighborhoods with poor public services—shares parallels with the indignation that has galvanized the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. Yet numerous French politicians and intellectuals decried the wave of French protests that took place after the murder of George Floyd as no more than a symptom of U.S. imperialism. How far have we come from the Enlightenment “sapere aude” motto that the French defenders of blasphemy claim to embody?

On February 1 Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin suggested that “we can’t talk with people who refuse to write on a paper that the law of the Republic is superior to the law of God.”

This commitment to imposing unanimity also works to obscure substantial tensions and disagreements among French citizens about laïcité. In addition to academics who oppose government projects to police speech and thought in the university, many non-Muslim religious leaders are skeptical of the caricatures and notions of blasphemy in circulation today. After the terrorist church attack in Nice, Monsignor Le Gall, the archbishop of Toulouse, suggested that spaces of peace, introspection, and kindness were more necessary than the right to blasphemy. More recently Protestant and Catholic leaders have expressed reservations about the bill’s impact on religious freedom. Hugues Portelli, president of the Catholic Academy in France, a Catholic advocacy group created in 2008, has warned against replacing the relationship of trust between the state and religious groups with one of fear and suspicion.

While numerous religious leaders have expressed concerns about the law’s impact on religious freedom, the conclusions they draw differ. Some emphasize the problematic restrictions on religious freedom implied by the law, others suggest that the law should more clearly target Islam as a “problem religion” or Islamic extremism. “This is a project that targets one issue and that strikes another issue,” declared François Clavairoly, the president of the French Protestant Federation to Le Monde. “There is indeed a threat, but the bill precisely targets those who play by the rules of the Republic.”

Official associations of Muslim leaders are also divided about the bill. Most Muslim French citizens perceive it as stigmatizing and are mystified by official Muslim organizations’ reluctance to critically engage with its wording. Within Parliament, a thin veneer of consensus belies the numerous divisions surrounding the proper extent of the restrictions in the proposed law. The extent of the administrative power of préfets over the monitoring of religious associations and the right to homeschool children continue to cause divisions among and within parties. To most participants in these polemics, it has become clear that the bill serves primarily as an instrument for Macron’s LREM (La République en Marche) to position itself as the main competitor of the far-right party RN (Rassemblement National, known until 2018 as the Front National, or FN) in the upcoming presidential election.

Proponents of the new bill to reinforce republicanism seem to see Islam as a threatening rival legal order. The bill functions to turn dissent into heresy.

It is ironic that a law ostensibly intended to prevent separatism is in fact deepening divisions and stifling much-needed democratic debate. France’s League of Human Rights has spoken out in opposition to the requirement that all associations in France that receive public funding sign a contract pledging to respect republican values. Whether the gamble to appease the far right with an eye on next year’s presidential elections will pay off remains to be seen. But the serious consideration of this legislation at the highest levels of government has already had a chilling effect among Muslim French individuals, academics, and activists.