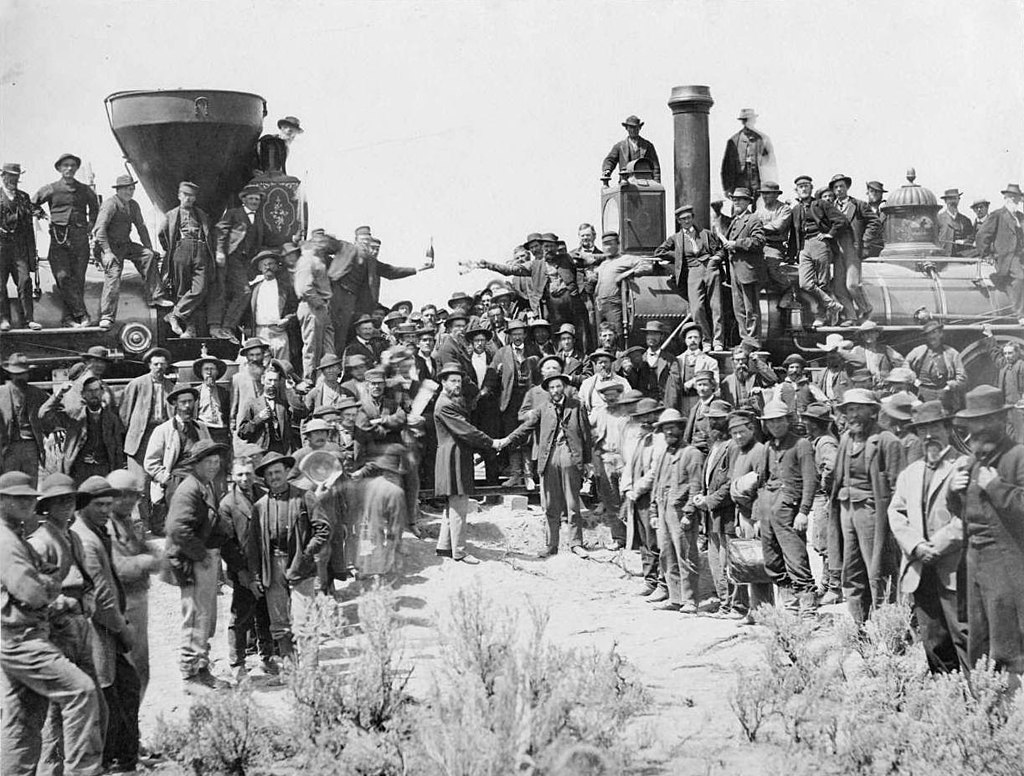

On May 10, 1869, a group of business leaders, politicians, workers, and journalists gathered beside the railroad tracks in Promontory, Utah, about eighty miles northwest of Salt Lake City. This area, located in Western Shoshone traditional territory, had been formally incorporated into the United States only nineteen years earlier. The group had assembled for a ceremony connecting the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, completing the first transcontinental railroad in North America. The ceremony climaxed when Leland Stanford, former governor of California and president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company, swung a silver-tipped maul to drive a golden spike into the ground, symbolically completing the last link in a rail line that now spanned the continent. The golden spike was promptly replaced with an actual spike and is now on display at Stanford University.

The ceremony one hundred and fifty years ago marked a moment of triumph for industrial capitalism, completing a hitherto utopian project of continental scale.

This ceremony one hundred fifty years ago is remembered as an iconic moment in the history of U.S. westward expansion. The golden spike sutured the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War. It marked a moment of triumph for industrial capitalism, completing a hitherto utopian project of continental scale. Given its focus on infrastructure, capitalism, and nationalism, the golden spike ceremony was a historical event that seems to speak, in startling ways, to central concerns of our own contemporary moment.

There are, however, other ways to understand the railroad’s significance, and its sharp resonance for our times. The Civil War had involved a massive increase in the size of the U.S. military. In its aftermath, the military occupation of Indigenous nations west of the Mississippi became a way to keep this behemoth running. Civil War veterans complained bitterly of winning a brutal war, only to be sent to suffer in Lakota country. Confederate prisoners of war, rehabilitated into U.S. Army soldiers, guarded railroad construction crews as part of this military occupation. Midwestern farmers and small businessmen had funded the Civil War effort through investments in new Wall Street financial institutions. Following the defeat of the Confederacy, railroad corporations became a primary outlet for reinvesting their capital.

This anniversary provides an opportunity for us to reflect on imperialism, racism, and genocide as core aspects of North American history.

Joining this nexus of war and finance was also government subsidy. The 1862 Pacific Railway Act, which chartered the Union Pacific Railroad and legislated the terms of railroad construction, directly contravened multiple existing treaties between the United States and tribal nations. The law granted tribal lands—lands the United States had explicitly recognized to be tribal lands—to the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies. These expropriated lands provided a foundation upon which corporations raised capital for construction. The transcontinental railroad was therefore less an achievement of economic competition than a product of colonialism and military occupation.

And it was built by bonded labor. The railroad companies employed a multiracial labor force, including thousands of immigrant Chinese workers, who were organized and paid along racial lines and disciplined by racist violence. After the railroad’s completion, a movement against Chinese immigration fanned outwards from California, culminating in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. In 1885, white people killed between twenty-eight and fifty Chinese miners who were working in a Union Pacific coal mine at Rock Springs, Wyoming, touching off a wave of anti-Chinese violence across North America. A year later, in 1886, the Supreme Court would find that the Southern Pacific Railroad Company enjoyed the rights of persons as enunciated in the Fourteenth Amendment—a finding that shapes U.S. corporate law to this day.

War and military occupation, Confederate rehabilitation, racist violence, abridgement of tribal sovereignty, massive corporate monopolies, anti-immigrant politics, and corporate personhood are some of the historical resonances of the transcontinental railroad for our own moment. It is relevant to note then that at the golden spike ceremony, Stanford actually missed the spike, though his errant swing was glossed over in most of the newspaper accounts of the event. The journalists wanted to tell a different story: one of the triumph of ingenuity and progress. Like Stanford, their stories missed the mark. This anniversary provides an opportunity for us to reflect on imperialism, racism, and genocide as core aspects of North American history, rather than exceptions to the proposition of U.S. exceptionalism.

U.S. nationalist mythology naturalizes the North American continent as the “homeland.” The golden spike anniversary makes it seem that there never was any alternative. But with the recent United Nations report that capitalism has spurred the sixth major extinction in planetary history, with over one million species at risk of disappearance, it is worth focusing on the ongoing, contested nature of claims to ownership and jurisdiction of Indigenous lands. As we look back at the golden spike, a more accurate perspective would have us see North America as the space of hundreds of colonized Indigenous nations.

The choice we face is decolonization or mass extinction.

This insight can make our internationalism more concrete. Of our current moment, Samir Amin, the long-term director of the Third World Forum, wrote, “To bring the militarist project of the United States to defeat has become the primary task, the major responsibility, for everyone.”

In North America, the longstanding call from Indigenous nations to honor the treaties deepens our anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist practice in a way that prioritizes and proceeds from Indigenous life and knowledge. Amin argued that the task at hand, in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, is to “abolish the still-present heritage of . . . historic conquest.” In our moment, the choice we face is decolonization or mass extinction. There is no alternative.