On June 22, as Pride month reached its crescendo, philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, whose recent work focuses on the politics of identity, took to the pages of the New York Times with a surprising argument: gay history focuses too much on gay agency. Specifically, Appiah contends that the focus on the 1969 Stonewall uprising, feted as the beginning of the U.S. gay liberation movement, propagates a “myth of self-deliverance” that, “whatever its value as a personal goal, is a lousy political ideal.” His chief complaint is that “for the sake of a ‘usable past’,” queer history focuses too much on narratives in which “the oppressed defy and ultimately defeat their oppressors.” This tendency has left queer people with a lopsided view of “how social progress happens” that makes history far less usable than it might otherwise be.

What is queer history’s relationship with political liberation?

“The most usable past of all,” according to Appiah, would accord more prominence to figures such as British Member of Parliament Leo Abse, a straight Jewish man who in 1967 successfully led an effort to repeal Britain’s sodomy law. In Appiah’s telling, history is meant to instruct future action, and only by resigning ourselves to the “unglamorous tale” of incremental progress through legislative dealmaking will queer people see their way to a liberated future. In short, we ought to pay less attention to the partisans on Christopher Street and more to the straight, white, cisgender men who actually did the work of reforming laws in the last half century.

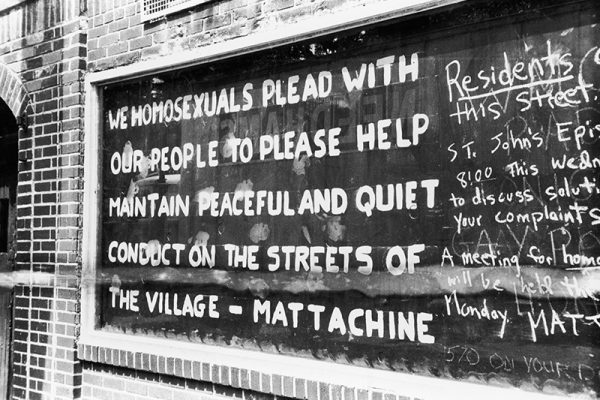

In his broader plea for historians to “accommodate the complex history of social change,” Appiah is, of course, not saying anything controversial. But in its details, the essay argues for a curiously old-fashioned sort of history, one that foregrounds the role of the privileged at the expense of those on the margins. The Stonewall riots present an easy target for this argument because they stand among the rare well-remembered moments of queer history (as opposed to the Compton Cafeteria riot, the West Berlin Pentecost marches, or the work of the Parisian Homosexual Action Front). But for all the problems with how we memorialize Stonewall, you would be hard-pressed to find a historian of sexuality who argues that getting the history right depends on doing less to center the experiences, for example, of black and trans activists such as Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, who helped lead the charge in June 1969.

At base, it seems that Appiah’s beef is with queer history, so perhaps we should begin by asking: What exactly is queer history, and what is its relationship with political liberation?

Queer history is related to, but not synonymous with, the history of sexuality. Queer history is often explicitly allied with other histories of marginalized groups and more closely tied to activism than is the history of sexuality. But insofar as Western queer history is primarily interested in the history of human sexuality, it stretches back to the earliest gay rights movements of nineteenth-century Germany.

Some of the first people in modern history to speak of homosexuality as a distinct identity were German lawyers and scientists. In 1869 Austro-Hungarian writer Károly Mária Kertbeny coined the term Homosexualität in a plea to the Prussian government to do away with its sodomy law. Later in the century, the famous sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing focused on defining homosexuality as a biological (or sometimes psychological or psychiatric) condition. He and his contemporaries believed doing so would prove homosexuality was natural, which would in turn convince governments to abolish sodomy laws.

Wrapped up in that desire to prove the naturalness of homosexuality were efforts to catalog famous homosexuals of centuries past. Emergent homosexual activists—most of them well-educated men—referred their readers to Frederick the Great, Alexander the Great, and Leonardo da Vinci, among others, as proof of homosexuality’s historical ubiquity. Such catalogs were, in essence, gay history—the history of great gay men (and an occasional woman, such as Sappho)—and they suffered from the prejudices and proclivities of their writers. But they also existed primarily as political tools, as handmaidens to the argument that the law should not punish gay people for their sexuality.

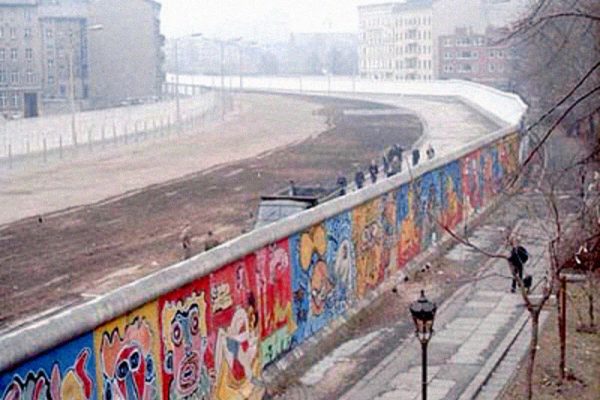

This version of the history of sexuality fell out of favor later in the twentieth century (though echoes of it linger still) and began to change in a noticeable way in the 1970s. In West Germany, writers harkened back to Germany’s queer past as a way of defining gay liberation efforts in the present. Not only did they focus on the queer effervescence of the Weimar Republic, but they also increasingly dedicated themselves to publicizing the Nazi-era persecution of queer people. This was the decade in which Michel Foucault published the first volume of The History of Sexuality (1976), still the foundation of the modern discipline. In 1980 John Boswell wrote Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, another classic. Both of these works—similar to efforts in West Germany—looked not to the famous gay men of the past, but rather to everyday experiences, to questions of persecution and liberation, and to rescuing ordinary queer people from—as British historian E. P. Thompson wrote in a different context—“the enormous condescension of posterity.”

To say that the powerful, the privileged, and the well-connected ‘get the Wite-Out’ in history books is untrue.

These writers were often allied to gay liberation efforts or other contemporary social movements. Jeffrey Weeks, author of Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present (1977), was a member of the London Gay Liberation Front. In 1976 activist historian Jonathan Ned Katz published Gay American History, a massive documentation of queer life in the United States that, as Jim Downs argues in Stand by Me (2016), “single-handedly created a subfield in US social history.” Part of gay liberation was to begin to tell queer history in a complex way, to recover stories not only of the exploits of famous gay men, but also of everyday life, of culture and political struggle, of—in Appiah’s words—“how social progress happens.”

In recent decades, queer historians have challenged these works as well, arguing that they do not do enough to center accounts of those who are not white, cisgender, and male. In addition, they reject out of hand triumphalist narratives, contending that these efface the experiences of the marginalized. Like earlier generations of historians of sexuality, these scholars often conceive of their work in an activist context. Since the 1970s, queer history has occupied a space between activism and the academy, with both scholarly concerns and presentist imperatives informing its progress. As a result, the field has grown from one focusing primarily on the exploits of famous men to one concerned with queer people of color, women, transgender individuals, prostitutes, and the working classes.

But you would not know any of this from Appiah’s rendition of queer history. In his view, there is too much focus on how “the oppressed defy and ultimately defeat their oppressors” and not enough on “the drudgery and temporizing of lawmaking and coalition building.” But history for far too long was only the history of men such as Leo Abse, and queer history for far too long was the history of the influential and powerful.

In fact, if we think of the best-known heroes of gay liberation in the United States today, they are often precisely the kinds of influential, privileged figures that Appiah tells us are forgotten: Justices Anthony Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, former president Barack Obama, and lawyers David Boies and Ted Olson, to name just a few. These individuals deserve the credit due to them, but to say that the powerful, the privileged, and the well-connected “get the Wite-Out” in history books is untrue. Indeed, it is not even true of Abse. His efforts to reform the UK’s sodomy law were recently featured in the BBC’s much-lauded series A Very English Scandal. A quick Google search pulls up numerous contemporary news stories about Abse and his contributions are well covered in contemporary historiography. He was also celebrated in a British gay history exhibition at the British Library that was one of the best attended shows in the library’s history.

In addition to contending that queer history focuses overmuch on the marginalized, Appiah also argues that historians of sexuality and queer activists are wrong on the question of how progress comes about. It is a question I have grappled with in my own research on gay German history, and to which I have found some surprising answers.

Take West Germany’s federal elections of 1980 as one example. On July 12, 1980, West German gay liberation groups staged an event unique in queer history. They had invited representatives of the country’s major parties to Bonn, its capital, for a debate on gay political priorities. What is more, those parties had accepted the invitation. In the city’s mammoth Beethoven Hall, in front of an audience of 2,000 lesbians and gay men, politicians would be asked to debate, among other things, reparations for Nazism’s gay victims and equalizing the age of consent.

Although the event was a flop (pedophile activists interrupted and shut it down before fifteen minutes had passed), it was only one piece of an electoral strategy that activists had planned for the 1980 election. They hoped that by mobilizing gay support for sympathetic parties, they might amplify their voices in the halls of government. Liberation groups campaigned in particular for the liberal Free Democratic Party, whose platform was amended that year to include a paragraph on homosexuality. “Continued discriminations must be abolished,” it read, “in order to grant homosexuals legal and social equality.”

Appiah is correct that change often takes the form of new laws, but those laws frequently come about because of the determined activism of small groups.

These efforts were the culmination of a decade of organizing and brought about a subtle but important shift in favor of gay rights among the decision-makers in Bonn. Activists worked to build alliances with party structures, sometimes even warning that politicians were missing out on a huge reservoir of untapped gay votes. But, crucially, these men and women were not asking for benevolence, as Appiah puts it, but rather making demands of their country’s representatives. The 1980 federal election, in which gay activists helped the Free Democratic Party win over a million more votes, is an example of precisely the kind of titanic impact the politics of self-deliverance can have.

Likewise, as I have written for Boston Review, activists in East Germany began organizing in the 1970s, hoping to convince the communist dictatorship to take their desires and needs as gay men and lesbians seriously. These activists eventually succeeded in pressuring the regime to implement a sweeping program of pro-gay policy. Again, not so much the politics of benevolence as the politics of self-deliverance.

Even in the case of the United Kingdom, Abse did not achieve reform alone. As Appiah mentions, Abse built on the work of the 1957 Wolfenden Report, which had advocated reform, and worked with the Homosexual Law Reform Society. Since 1962 the Society had been led by Antony Grey, a gay journalist and lobbyist whom Lord Arran (Abse’s ally in the House of Lords) said had “done more than any single man to bring this social problem to the notice of the public.”

Appiah is naturally correct that the most visible change often takes the form of new laws, but he skates over the fact that those laws frequently come about because of the determined activism of small groups.

Stonewall is just one of many potential examples of this sort of political engagement, and I find it unhelpful that Stonewall has eclipsed similar revolutionary moments in other countries or even other parts of the United States. I have found, for example, that German gay men and lesbians are often convinced that West German liberation efforts grew out of Stonewall and were only an ugly stepchild of the U.S. gay liberation movement that grew up in the 1970s. But, in fact, many of West Germany’s activists had not heard of Stonewall when they began organizing in 1971. And their agitation did much to remake West Germany. Der Spiegel, West Germany’s periodical of record, noted by 1979 that gay demonstrations were “habitual street scenes.” Because of these activists, who preached an ideology of gay power, political parties put homosexuality on the federal agenda for the first time since the Weimar era. The image of Stonewall can efface the significance of such exertions.

But Stonewall was deeply significant. It was a revolutionary moment that a new generation of activists steeped in other progressive causes used to push gay efforts in a more radical direction. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF), founded in 1969 in Stonewall’s immediate wake, was a boisterous coalition of youthful campaigners fighting not only for gay liberation, but also for anti-imperialism, civil rights, feminism, trans rights, and socialism. And not only in New York: there were gay liberation chapters all over the country as well as abroad, and their protests pushed for changes to local and state laws. Ironically, gay liberation aspired to the very sort of political alliances that Appiah would have us believe Stonewall teaches us to ignore. Though the GLF was short lived, it and other post-Stonewall organizations had an indelible impact on gay political consciousness in the United States.

Indeed, gay liberation efforts in the United States have won queer Americans alliances with rather powerful interests. While we are far from arriving at any kind of queer utopia, it is not in every country that an attorney general declares, as Loretta Lynch did in 2016, “Let me also speak directly to the transgender community . . . we stand with you; and we will do everything we can to protect you.” Even if our standard is the building of political alliances, Stonewall’s progeny looks remarkably successful.

Appiah’s essay could be read as advancing a view of history in which progress only happens through the exertions of the powerful. This calls to mind the famous nineteenth-century German historian Leopold von Ranke, who is today best remembered for the injunction to tell history “as it was.” The statement’s bland empiricism effaces what it came and continues to mean—namely, that history was to be written by those who left the richest documentation, a history of great men doing great things.

For well over a century, that is precisely what academic history was. The experiences and significance of women, the working class, non-white, and queer people were hardly if ever mentioned.

Queer history matters because it helps queer people understand and shape the world around them.

The German theorist Walter Benjamin hated such history. Writing in 1940, while on the run from the Gestapo, he flatly rejected Ranke’s injunction and argued, “To articulate the past historically . . . means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. . . . Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.” Each age has its own monsters, and historians—professional and grassroots alike—should aspire to write histories adequate to the task Benjamin set: to make the past a tool in service of the living.

Queer history matters in large part because it helps queer people understand and shape the world around them. Since the nineteenth century, the history of sexuality has played an important role in queer political movements. It will likely continue to do so in the future. On this, I believe, Appiah and I agree.

Where we disagree is in what will make for “the most usable past of all.” To my mind, public interest in the past is the reason why Stonewall and other moments like it are indispensable to the telling of queer history. As a historian I am interested in finding voices beyond those recorded in parliamentary minutes, because such histories paint a richer, more interesting, and ultimately more informative picture of the past. On the question of how change happens, they reveal that progress rarely comes from the contributions of individuals such as Abse alone, but rather through the sustained efforts of activists often relegated to the margins.

The point of history is not merely to catalog facts, but also to make sense of those facts in ways that help us both understand the world around us and imagine new futures. Through history we see how things might have been and may yet be different.