Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993

Sarah Schulman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $40 (cloth)

Let the Record Show, Sarah Schulman’s monumental new history of ACT UP New York, is a war chronicle in which the teller is both scribe and veteran. Schulman joined the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) a few months after it was founded in 1987. At that point, six years into the crisis, there were an estimated 500,000 people living with HIV in the United States alone, there were still no effective medical treatments, and the U.S. government’s anemic response to the pandemic was a toxic cocktail of homophobia and hysteria.

ACT UP burst onto this scene determined to confront apathy and create change on every level, from getting new drugs approved to creating alternative media through which to disseminate accurate information about the crisis. As the founding chapter, ACT UP New York was “the mother ship,” but 148 other chapters, all acting autonomously, have since sprung up around the globe. Unquestionably, they have been one of the most effective activist movements in modern U.S. history—though as Schulman chronicles, their successes did not come without great costs. In fact, Let the Record Show is in part a grand accounting, tallying up what was won, what was lost, and the process through which those battles were fought. Only by this kind of rigorous analysis can the lessons of ACT UP be passed on to current and future activists.

By the time she joined ACT UP, Schulman had already been writing about AIDS for four years, and it has remained a focus of her work ever since. Prior to Let the Record Show, she published several other nonfiction books that significantly dealt with AIDS, and four novels as well. In 2001, with fellow ACT UP member Jim Hubbard, she created the ACT UP Oral History Project, through which they conducted long-form video interviews with 188 members of ACT UP NY over the course of seventeen years.

Let the Record Show is a work of considerable formal daring composed almost entirely of quotes taken from those oral histories, woven together with summaries and interstitials that cohere those voices into a narrative. As Schulman writes in her preface, “this is a book in which all people with AIDS are equally important.” This isn’t hollow rhetoric: one of Schulman’s overarching themes is that ACT UP was most effective when it had the broadest coalition of members, and that even its narrowest successes—the ones that seemed to stem from or give benefit to just a small section of the group—were only possible because of the power of the broader collective. As such, the story of ACT UP could not be accurately told in a traditional narrative format that focused on a few “heroes” and their journey. Unfortunately, as Schulman points out, this is all too often how ACT UP has been historicized, particularly in films like How to Survive a Plague (2012), which focused on a small group of white cisgender gay men who worked with the government to develop new drug treatments.

Let the Record Show resists this narrow framing, and instead uses a choral structure, weaving together many voices and letting none dominate. Schulman doesn’t replace one set of heroes with another; rather, she destroys the idea of singular heroes at all. This is a political choice that creates a more honest representation of ACT UP, and it is a strength of the book—but like all strengths, it contains its own weakness. To make room for these voices, Let the Record Show weighs in at over 700 pages. It at times can get repetitive, and the equal weighting of every voice can flatten their particulars, making it easy to lose the thread of who is speaking at any given moment. Let the Record Show is a powerful resource: no one will henceforth write about ACT UP without referencing it, but it is a book few are likely to read straight through. For this reason, Schulman has divided the text into four major thematic sections, and includes an introductory note on how to read it.

However, despite its many voices, Let the Record Show is unquestionably the product of Schulman’s unique vision. Readers familiar with her work will see her fingerprints everywhere: in the analysis of the ways in which disagreements among allies can morph into projections of enemies (Conflict Is Not Abuse, 2016); in the examination of the psychic toll of homophobia, marginalization, and family rejection (Ties that Bind, 2009); and in her nuanced understanding of political tactics (Israel/Palestine and the Queer International, 2012), to name just a few.

But this is no retreading of familiar ground. Instead, it feels like the capstone of a career. Fighting AIDS helped Schulman to understand everything: politics, family, poverty, power, gender, race, sexuality, theater, narrative structure, and the world. Now she is bringing the resulting revelations back to bear on the fight against AIDS itself, and we are all the richer for it.

Schulman imparts many lessons in Let the Record Show, but reading it as the world was engulfed in another global pandemic, one rose to the top: activist movements must set their priorities from the bottom—from those who have the least; those who need the most—or their success will always be partial. The most salient thread we can draw from Let the Record Show is an understanding of how mass movements can succeed and fail, all at the same time, depending on which part of the “mass” you’re in.

Schulman describes Let the Record Show as a political history, and the book’s opening section, “Political Foundations,” analyzes the strategies through which, as she succinctly puts it, “change is made.” This section is deeply practical, and today’s activists—whether in the Movement for Black Lives or the fight for trans rights—will find it instructive. Schulman examines concrete strategies, why they appealed to (or were only possible for) certain groups, and how those strategies changed both their targets and the activists who undertook them.

“The only requirement” for an ACT UP action, Schulman writes, “was that it was direct action, with a goal related to ending the AIDS crisis.” She makes clear that symbolic actions, or protesting for protesting’s sake, is only an option for those who have time to waste. ACT UP actions always had specific, tangible results in mind, and their targets were chosen because they had real power. Because they and their friends were dying terrible imminent deaths, ACT UP embraced simultaneity, freeing each member to work on actions that mattered to them, in the way that made most sense given the material reality of their lives. There was no formal approval process for actions. People proposed ideas at ACT UP’s Monday night meeting, and others joined if they wanted.

For instance, when they wanted to draw attention to the pathetic speed of approvals for new medications, ACT UP went en masse to the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration, which oversaw the approval process. Within this larger protest, small clusters of friends—called affinity groups—planned their own actions, from storming the building to connecting media outlets with AIDS activists in their home regions.

This multipronged approach enabled ACT UP to quickly wrack up wins on many different issues, including “design[ing] a fast-track system in which sick people could access unapproved experimental drugs” and making needle exchange programs legal in New York.

Using diverse tactics to achieve diverse goals was a strategy that drew on the unique strength that came with being an organization rooted in queer life, as Schulman elucidates in the third section of Let the Record Show, “Creating the World You Need to Survive.”

Queerness is not a vertical identity. It hopscotches across communities, blessing only some of us. Thus, the membership of ACT UP was incredibly diverse, yet still united by the extreme marginalization of being queer people and people with AIDS. Shared oppression doesn’t automatically create solidarity among people from different backgrounds, but it does create moments of overlap, echoes of experience that provide potential foundations from which to build. This was key to the success of ACT UP—the ability to imagine a shared, better world—and it is a reminder for activists today that to create change, a building up must always accompany a tearing down. As Schulman writes:

Having been excluded and ignored by straight power for generations, deep undergrounds of queer opposition were built in which our needs and realities could be reflected and expressed and in which our authentic concerns could be engaged.

These “deep undergrounds” facilitated the creation of alternative health collectives, alternative research practices, and alternative media—a whole parallel society, really. Underpinning all of it was a set of alternative values—radical solidarity, empathy, honesty, celebration of difference, and a refusal to be passive in the face of injustice—which were developed from (and necessary for) the experience of being connected to a diverse yet marginalized community.

What gave this subculture its manic energy and urgency was, of course, the ticking clock of AIDS:

The emergency forced those who took responsibility to try to create solutions, at great levels of commitment and effort. Because we wanted to win, which meant to live, ACT UP had to rise to reality and create solutions to problems created by government indifference and incompetence, while continuing to insist that this work was the responsibility of the government and private industry. It was a simultaneous approach of literally designing change while escalating pressure on the society at large to step up and be accountable.

Here again, however, is the double-sided coin of strength and weakness: urgency fueled ACT UP’s embrace of simultaneity, which empowered them to make change. But at the same time, simultaneity allowed some factions to race off in their own direction, inadvertently hobbling the organization as a whole, even as they achieved laudable goals.

In particular, the Treatment and Data (T&D) committee of ACT UP NY (which was mostly, but not entirely, cis white gay men with class privilege—the people often treated as the “heroes” of ACT UP) cohered around a highly effective strategy of working with the government to get more drugs approved. Since these men had health insurance and financial security, a lack of approved drugs was the critical limitation that condemned them to die agonizing early deaths. And because they resembled the people in power in critical ways, negotiating with them was a viable strategy. Government authorities would take their meetings, and these men’s immediate needs could be met without overturning capitalism, tearing down our system of mass incarceration, or rejecting the United States’ corporate approach to health insurance. In other words: their preexisting proximity to power meant powerful people would listen to them, and that their issues could be addressed without fundamentally altering the powers that be.

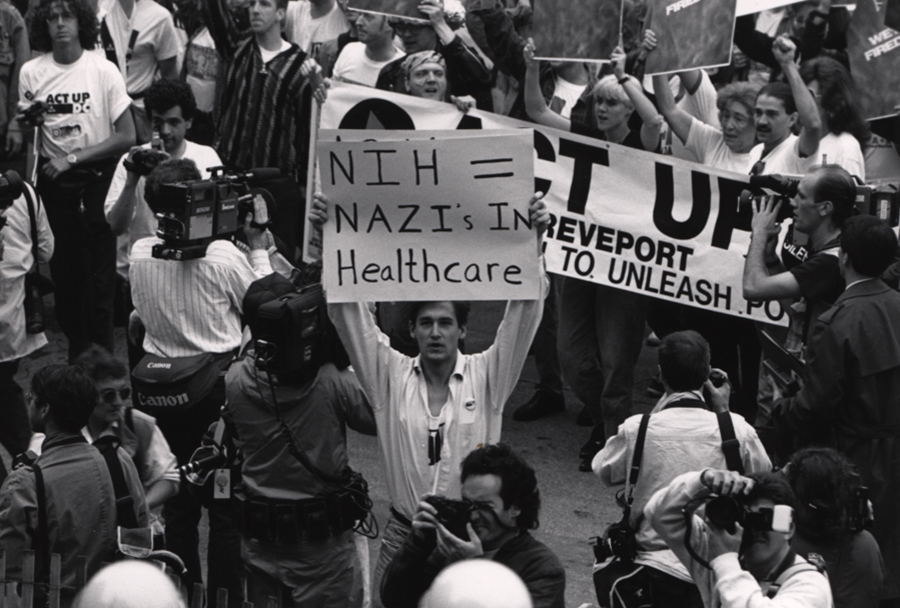

During the six years that Schulman was a member of ACT UP NY, “the gap between what levels of access different activist constituencies had was growing, and in many ways, determining group consciousness.” This deepening division eventually led to the group’s fracturing in 1992. Schulman outlines this traumatic break in the final section of her book, “Desperation,” tracing it to the famous May 21, 1990, action called “Storm the NIH.”

The National Institute of Health (NIH) was located in Bethesda, Maryland, and getting ACT UP NY down there required a massive mobilization, with months of planning and over $60,000 in expenses. The official demands for the action included testing “all potential treatments immediately” and devoting more research to opportunistic infections. In reality, however, the men of T&D had a narrower goal: to get their members placed on government committees, where they would have more direct power to affect long-term change. But, as Schulman notes, “this was not made explicit” to the group as a whole, and as she interviewed ACT UP members for the Oral History Project, “almost no one could tell me . . . what the demands were for this action.”

Afterward, because most participants had no clear understanding of, or agreement with, the goals, there was little feeling of shared success. As Schulman explains:

The manipulating, the false fronts and puppet mastering, even just the difficulties with emotional communication, i.e., the method used by some of these men, represented values and created a feeling of unease among some of the membership. It telegraphed a feeling of superiority and disrespect. . . . Perhaps the membership of ACT UP, those who normally occupied the Outside role, would have supported the same goals, had the goals for the NIH action been honestly stated, but they certainly would have demanded a more varied group of individuals represented ‘at the table.’

Even if that had been the outcome, however, Schulman astutely notes that those government committees might well have just ignored the “dykes, street queens, and women of color” that joined, as “none of the above were represented in government, media, or pharma” already.

It is in this complicated space, where success and failure comingle, that Schulman’s complex understanding of activism shines. She never shames the men of T&D for embracing their power, nor does she minimize their incredible achievements in overhauling the government’s approach to HIV medications. Perhaps what they gained through the Storm the NIH action could not have been gained in any other way; that is unknowable. Schulman is not interested in condemning the choices ACT UP members made, but in analyzing them honestly, in order to gain understanding that can be used by future movements. This spirit of open reflection is also part of the legacy of ACT UP, and helped make the ACT UP Oral History Project so powerful: in the course of conducting 188 interviews, “no one, in seventeen years, refused to answer a question.”

But Schulman also makes clear the long-term limitations of this “insider” strategy: as they effectuated change, these men removed themselves from the diverse community that made that change possible (literally: T&D formed a new organization, the Treatment Action Group, in 1992). These insiders could not have achieved the results they did without the “outsider” activists who worked against, not with, the government. But as their need for treatments got met, these relatively prosperous white gay men were no longer in the same place as other activists who did not have health care, or were imprisoned, or suffered the systemic devaluation of racism, or were women whose illnesses did not even qualify as “AIDS” in the eyes of the medical establishment. Although many of the men in T&D continued to be activists long after their own disease was considered a chronic manageable condition, “AIDS activism’s most radical and socially revolutionary vision evolved when those white men were in the same boat as everybody else who had AIDS: desperate.” This wasn’t because these white men were somehow more critical to making change; rather, everyone was critical, and the narrower the coalition of the desperate, the less they could achieve.

The men who successfully led the Storm the NIH action were indeed appointed to government committees, where they created new practices that are still the gold standard in AIDS research today. However, in these new roles, they also held cordial meetings with the same officials that the women of ACT UP were protesting for refusing to acknowledge that women had AIDS—a refusal that blocked them from treatment and was often a death sentence. Sometimes these meetings and protests were literally on the same day, undercutting the strength of the outsiders for the benefit of those now on the inside.

“The men of T&D were people with AIDS, desperate for new treatments,” Schulman writes empathetically, “and yet so were other people.”

Strategies and what-ifs can be debated endlessly, but results are results. Perhaps the most damning assessment of the cost of this fissure is a simple fact that Schulman notes in her preface: “By 2001 almost every HIV-positive woman in ACT UP New York, except for one confirmed survivor, had died.”

ACT UP’s members achieved incredible wins, against impossible odds, while watching their world crumble around them. They made mistakes and kept going, literally carrying each other when necessary. A few hundred dying people battled the United States, and often they won. Reading Let the Record Show made me wonder what they could have done with more bodies on the line; more help; more hands; more heart; more anger. “Unfortunately, most people do not participate in making change,” Schulman notes. “Only tiny vanguards actually take the actions necessary, and even fewer do this with a commitment to being effective.”

Many of ACT UP’s women—and men, and nonbinary people—fought effectively to their dying breath. Others survived and are still fighting. They succeeded in changing the definition of AIDS to include women. They brought HIV services into detention centers. They made films about the crisis. They are still making films about the crisis. They are writing histories that tell their successes and failures with clear eyes, to enable us to make better choices in the future.

But this story is inherently unfinished; AIDS is still a crisis; activists are still fighting today. ACT UP New York meets every Monday at 7:00 p.m. at the LGBT Community Center in Manhattan.

Everyone is invited.