Donna Murch is right that the rhetoric on drugs has softened along racial lines. The dominant narrative now mostly describes working-class white victims in rural states, despite recent data showing that drug death rates are rising sharply for African Americans. Prior drug “crises,” such as those involving crack and heroin, were seen as inner-city issues that exclusively affected people of color, who were rarely extended the moral purity of victimhood. This racial transformation has led lawmakers, law enforcement, and mainstream media alike to display more compassion toward people who use drugs, as exemplified by the 2015 New York Times headline “White Families Seek Gentler War on Drugs.” Yet public policies have not matched the rhetoric. Although in some cases we have moved toward a more health-centered approach to the overdose crisis, the rhetoric of compassion belies an ongoing and insidious entanglement with capitalism.

It is true that the government’s response to the opioid epidemic has differed markedly from earlier drug panics. Traditional upticks in drug use—whether crack in the 1980s or methamphetamine in the 1990s—were met (under the Reagan, Clinton, and both Bush administrations) with an enforcement-centered response: tougher sentences, narcotic task forces, more prisons and law enforcement funding. The overdose crisis, by contrast, has led lawmakers to call for compassion and treatment. Under Obama, Congress passed legislation aimed at tackling the overdose crisis with a public health focus. Both the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act and the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in 2016, poured billions of dollars into treatment. But beneath this compassionate approach, many of the quintessential characteristics of the drug war persist—fueled by money and power, not evidence.

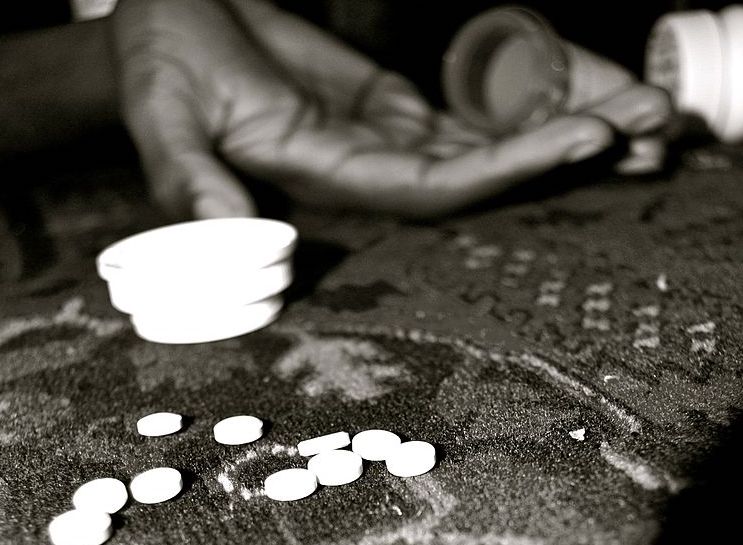

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is a case in point. Despite overwhelming evidence for the efficacy of methadone and buprenorphine, the gold standard treatments for opioid use disorders, the government still fails when it comes to following the research. Both treatment options have decades of evidence demonstrating their effectiveness in reducing overdose deaths, yet they are increasingly superseded by a third medication for opioid use disorder, naltrexone. This drug’s domination of the addiction field in recent years is partly driven by money.

According to the New York Times, the company that manufactures the drug under the brand name Vivitrol “has spent millions of dollars on contributions to officials struggling to stem the epidemic of opioid abuse. It has also provided thousands of free doses to encourage the use of Vivitrol in jails and prisons, which have by default become major detox centers.” Unlike methadone and buprenorphine, which are carefully regulated opioids, Vivitrol literally blocks opioid receptors, making it a kind of forced abstinence drug. Yet the evidence base for Vivitrol, compared to that for methadone and buprenorphine, is weak. It is also far more expensive, at around $1,100 per injection. Nonetheless, naltrexone has received millions of dollars in government funding as well as some heavyweight endorsements. Trump’s first health secretary, Tom Price, stated that though he supported MAT, he disapproved of methadone and buprenorphine because they “simply substitute” one drug for another. Vivitrol lobbyists have also successfully had it added to numerous pieces of state and local legislation at the exclusion of the other two, rather than “letting the market decide.”

The expansion of drug courts is another example of the suppression of evidence-based policymaking, as lawmakers say one thing but do another. Drug courts have received millions in government funding during the overdose crisis. On one level, the bipartisan support for this intervention is easy to understand. Drug court advocates pitch the intervention as a way of connecting people to treatment without putting them through the traditional criminal justice system. Yet the reality is not so simple. Admission criteria are so restrictive that many are still forced to face the traditional criminal justice system. Judges are given the authority to make medical decisions outside of their scope of practice. Relapse can be cause for punishment, even though it is a typical component of substance use treatment and recovery. And evidence-based treatments such as buprenorphine and methadone may not be offered to participants—indeed, their use is often penalized.

Even treatment facilities themselves are fraught with systemic issues, including poor integration with traditional medical treatment, a lack of qualified and trained staff, limited implementation of evidence-based practices, and little regulatory oversight. The pharmaceutical deregulation Murch details has occurred alongside the explosion of the “rehab” industry, one of the most unregulated, reckless, and dangerous in health care. It is no surprise to see companies that run private prisons increasingly involved in a lucrative treatment-industrial complex worth $35 billion. It is not simply that these programs are a waste of money; poor-quality health care kills. People who do not get adequate treatment are at high risk of relapse and overdose.

And we must not forget that even if the United States has embraced the rhetoric (rather than reality) of compassion domestically, the same cannot be said for U.S. foreign policy. The United States has exported its drug war to Latin America and beyond, sending weapons and military support to corrupt governments across the world. Billions of dollars are spent and thousands of lives lost in places such as Mexico and Honduras, at the behest of the United States. There is no compassion here, rhetorical or otherwise. Instead we see the truth. The global war on drugs is about imposing U.S. policies and practices on countries with majority black and brown people. In 2006, when Mexico passed a bill decriminalizing possession of small amounts of certain drugs, including cannabis and cocaine, George W. Bush called President Vicente Fox and pushed him to block the bill. Fox obliged and vetoed it.

In short, though U.S. drug policy has tried to present a more compassionate face, it is still rotten at its core. The drug war continues unabated, with drug arrests and incarceration near record highs. It is simply taking on new forms, morphing to keep up with changing winds in public sentiment. The War on Drugs has always been about control—control of communities of color, control of countries, and control of capital, often under the guise of benevolence, paternalism, and compassion. Until we confront these truths, we will never begin to make real change.