As journalists and scholars have rushed to respond to the “populist explosion” in recent years, a broadly shared approach to the notoriously ambiguous concept populism has begun to take shape. In the populist effort to represent or incarnate the capital-P People’s sovereign will, scholars have identified a “political logic” naturally culminating in charismatic personalism or authoritarianism. On this account, the effort to speak and act on behalf of a morally pure and unitary people against the ruling power of a corrupted and unrepresentative elite inevitably threatens democracy. This is a view shared by many liberal critics of populism, and, in slightly modified form, by some advocates of left populism, as well. The appalling success of contemporary examples of popular authoritarianism around the world—from Modi to Trump, Erdogan to Bolsonaro—seems to demonstrate populism’s inherently anti-democratic logic.

Several contributors to this forum have written against this prevailing view, attempting to recover a more egalitarian, radically democratic, and institutionally experimental populist politics. One form that pushback takes is a return to populism’s diverse histories, especially in the Americas. This history offers not only a way of criticizing the crumbling liberal consensus from which the contemporary critique of populism often emanates; it also helps us envision different paths forward. This task is part of broader efforts to imagine and organize multiracial coalitions built around an emancipatory class politics. Debating whether we should call such movements “populist” is a semantic distraction: it too often mires us in unproductive verbal disputes or obfuscates ideological differences that should be engaged on their own terms. The urgent question is not what we call the politics, but what the politics should be.

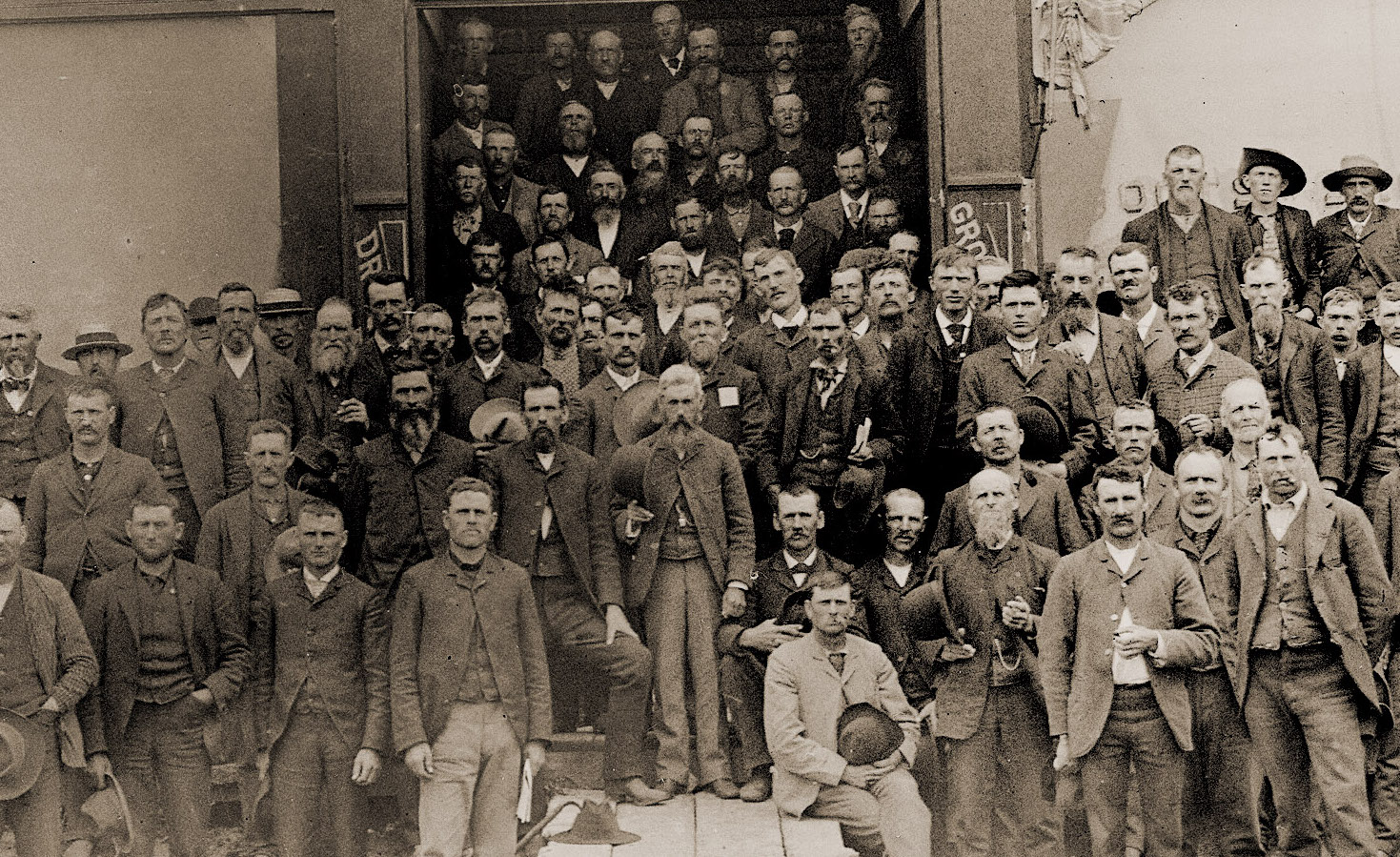

The histories many of us have drawn upon provide valuable exemplars of that politics, as well as counterexamples to common critiques. My own writing on these questions has focused on nineteenth-century populism in the United States—the Farmer’s Alliance and the People’s Party—and efforts to build what a wide array of radicals in that era called a “cooperative commonwealth” in the face of the social dislocations and radical inequalities of the first Gilded Age. Their experimentation has much to teach us about generating democratic power outside established institutions of governance—from the alliances and suballiances that proliferated in the 1880s, to cooperative economic organizations such as cooperative stores, commodity exchange pools, and lending agencies, to the formation of the People’s Party itself. These experiments in building a cooperative commonwealth contrast sharply with the authoritarian personalism so often decried by populism’s contemporary critics.

There is another influential liberal critique of populism, however, that may seem to have more force against nineteenth-century U.S. populism: what Nadia Urbinati has identified as populism’s intrinsic antipluralism. Others have argued, along similar lines, for populism’s close and perhaps inextricable ties with identarian politics. The idea makes it into the very title of William Galston’s recent defense of centrist liberalism, Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy (2018). But the nineteenth-century history is not quite so susceptible to this critique as many assume. We need not accept the ahistorical caricatures of populism found in books like Galston’s to recognize that the conceit of “the people” has too often and too easily been identified with “the Christian” or “the white,” or to confront the undeniable resonance between contemporary forms of popular authoritarianism and a reinvigorated identarianism around the globe.

The historian Richard Hofstadter influentially claimed that the “paranoid style” of American politics—and its recurrent appeals to nativism, xenophobia, and bigotry—had its origins in nineteenth-century populism, but this argument has been thoroughly dismantled by a mountain of subsequent scholarship. Nineteenth-century populism in the United States was clearly not an identarian movement. It was a farmer-labor working class movement that aimed, in the language of the Omaha Platform, “to restore the government of the Republic to the hands of the ‘plain people,’ with which class it originated.” The question of racial division was a deeply contested part of U.S. populism from the very beginning: How could it not be, in the wake of Reconstruction and alongside the emergence of white supremacist “Redeemer democracy”? White supremacy and its institutional expression in the form of the Democratic Party contributed powerfully to the collapse of white and black populism in the late 1890s as the Jim Crow regime was established throughout the South.

The public life of Tom Watson, a Congressman and prominent populist leader from Georgia, is sometimes taken to exemplify the broader political transformations of the period. Watson’s early activism on behalf of the Farmer’s Alliance and then the People’s Party was defined by a remarkably forthright understanding of how the U.S. caste system was sustained by pitting white and black farmers and workers against each other. Addressing black and white southerners in 1892, at the high tide of populist radicalism, Watson proclaimed, “you are kept apart that you may be separately fleeced of your earnings. You are made to hate each other because upon that hatred is rested the keystone of the arch of financial despotism which enslaves you both.” By the end of the century, Watson was one of the South’s most famous advocates of black disenfranchisement and Jim Crow.

Watson’s dramatic reversal on the promise of interracial class coalition was reflected more broadly across the complicated and often contradictory terrain of populist politics in the 1880s and ’90s. Many historians have emphasized and valorized populist efforts to pursue what Lawrence Goodwyn called “the most radical dream of all—a farmer-labor coalition of the ‘plain people’ that was interracial” while also detailing the obstacles both within the movement and external to it that prevented this dream from becoming a general feature of populist radicalism. During this period white and black populists organized boycotts and strikes together and occasionally built successful political campaigns against the entrenched Democratic establishment, and they did so in the face of almost inconceivable political opposition, intimidation, and violence.

The political successes and failures of these “adventurous innovations in interracial politics”—the phrase is Goodwyn’s—were distributed unevenly across the geography of the alliances and suballiances and within the People’s Party itself. The Southern Farmer’s Alliance, for example, never allowed black membership at all, and the Colored Alliance responded in kind, although in practice it had white membership and officers. The fraught question of racial coalition was often a source of conflict between Northern and Southern organizers and became especially acute with the efforts to establish a national People’s Party beginning in the St. Louis Convention of 1889. Northern leaders such as Ignatius Donnelly could propose to wipe the Mason Dixon line out of geography and wipe the color line out of politics, even as Southern delegates sponsored measures to segregate the floor of the convention itself.

The familiar divisions between North and South, however, are not themselves adequate to explain populist conflicts over race or the dynamics of interracial coalition within the movement. For one thing, the most politically successful example of populist interracial coalition was in North Carolina, where North Carolina Republicans forged a fragile but successful “Fusionist” coalition with black and white populists to triumph over state Democrats in 1894. This political success was fleeting, however, in that it provoked a violent political backlash that set the stage for the “white supremacy campaign” of 1898 that culminated in the Wilmington massacre and the violent overthrow of the democratically elected government.

More recent historical scholarship, especially the work of Charles Postel and Omar Ali, has argued that in many respects there were two separate populist movements: a white populism and a black populism, each with its own distinctive institutions and goals, with black populists’ goals typically more radical and pushing the movement to the left. Black populists consistently advocated for the interests of sharecroppers and propertyless tenant farmers. They also helped mobilize third-party radicalism within the movement. While they worked toward many of the same economic goals as white populists, they campaigned against the growing institutionalization of white supremacy in the South in the wake of Reconstruction, opposing the wide array of discriminatory legislation passed in the 1880s and ’90s, such as separate coach laws, the exclusion of black jurors, and the convict lease system. They also let the demand for federal oversight in public education and the electoral process. White populists did not prioritize any of these issues.

This scholarship helpfully corrects an earlier generation’s overly optimistic accounts of interracial cooperation in this period, but it also risks committing the error that Erin Pineda discusses: imposing a liberal grid of competing group interests and “identity politics” on these movements at the expense of engaging with their shared—however flawed and ultimately defeated—radical democratic project of peopling. The political theorist Sheldon Wolin once wrote that in popular struggles against inequality, the people aim “to transform the political system in order to enable itself to emerge, to make possible a new actor, collective in nature.” “The people,” on this view, is not the expression of a shared past, nor is it the fantasy of homogeneous identity. It is instead a form of political power that takes shape through concrete practices. Strengthening democratic power requires recovering a sense of political commonality across enforced lines of difference.

The collapse of the populist movement began in 1896 with the fusion of the People’s Party and the Democratic Party in the presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan. This political alignment led many white populists to abandon their former black allies, setting the stage for the Party of the South to destroy any remaining independent leadership within the movement and to declare war against its interracial coalitions, however imperfect. That war had its legal face in a wide array of black disenfranchisement and segregation laws, and its extralegal face in sweeping campaigns of bribery, fraud, intimidation, and terror.

This complicated history does not confirm common critiques of populism’s supposedly inherent antipluralism or identarianism. To the contrary, it testifies to the power of white supremacy, racial capitalism, and the institutional and structural obstacles to radical change. It was neither the first time nor the last that a movement of industrial laborers, farmers, and other working people have been undone by the politics of racial division. It is possible to acknowledge the risks of these abiding forces of division while also looking to these experiments as the imperfect but inspiring examples that they are.