Kate Soper makes an excellent critique of the obsession with consumerist gratification that is so widespread in rich capitalist countries (and, increasingly, among the rich in poorer countries). In this way, consumerism indeed serves as the lifeblood of contemporary capitalism. I completely agree with her point that “the overall aim must be to wrest control of global wealth and material resources from the grip—and accompanying ecological dereliction—of a relatively small corporate elite.”

There is no doubt, as I have written elsewhere, that GDP is a terrible indicator of human progress or even of material well-being. I believe that this is something that both those who argue for “green growth” and those who insist on the need for “degrowth” are agreed upon. All of us are concerned with achieving an economy that delivers our desired social goals: health for all; the ability to provide basic needs and develop human capabilities for everyone; the universal ability to contribute to and benefit from society; and living in harmony with nature and the planet.

The main barrier to achieving these goals is obviously the continuing power of big capital and its influence in state policies, aided by a short-termist approach that fails to even recognize the immediate dangers of ecological tipping points. Humanity is hurtling toward environmental, planetary, and social disaster, and patriarchal finance capitalism is our common enemy.

This forum response is featured in The Politics of Pleasure.

Economic and social strategies of both “green growth” and “degrowth” share this view, and they advocate similar if not identical economic and social strategies. So why should we obsess about whether GDP rises or falls as these strategies are implemented? What matters is the pattern of economic activity and the distribution of its gains. In some countries GDP might rise, and in others it might fall; these changes would be byproducts, ideally irrelevant ones. Insisting on degrowth is a distraction—probably a hugely counterproductive one—because it misses the point and alienates many potential allies.

Soper’s concerns about “presentism” and the need to consider previous forms of economic organization could well be justified. Awareness of past social orientations and ongoing efforts to revive them and implement their insights in some form are important. For example, the Quichua notion of Sumak Kawsay, which has been translated as buen vivir or living well, more correctly describes “a life with dignity, plenitude, balance, and harmony.” Ideas like Ubuntu in Africa and Swaraj in India also emphasize not just social cohesion but also harmony with nature.

But we should not romanticize life in the past, which in much of the world, until quite recently, could still be characterized, in Thomas Hobbes’s formulation, as “poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” In the long course of human history, one of the most striking features of the twentieth century—simultaneously a terrible time in many ways and for many people—was the dramatic increase in life expectancy in all the regions of the world. After around two millennia when average life expectancy is estimated to have remained broadly flat at around twenty-eight to thirty-two years, it started increasing in the nineteenth century in today’s rich (then, colonizing) countries. Over the twentieth century the average of world life expectancy doubled—and the gains were spread across countries. What is more, the gaps between countries, though still very large, have reduced since 1950. Max Roser notes that “today most people in the world can expect to live as long as those in the very richest countries in 1950.”

This historically remarkable change reflects major improvements in health: mostly (but not only) declining child and maternal mortality, improved nutrition, and containment of several infectious diseases. This is real human progress, which should not be discounted.

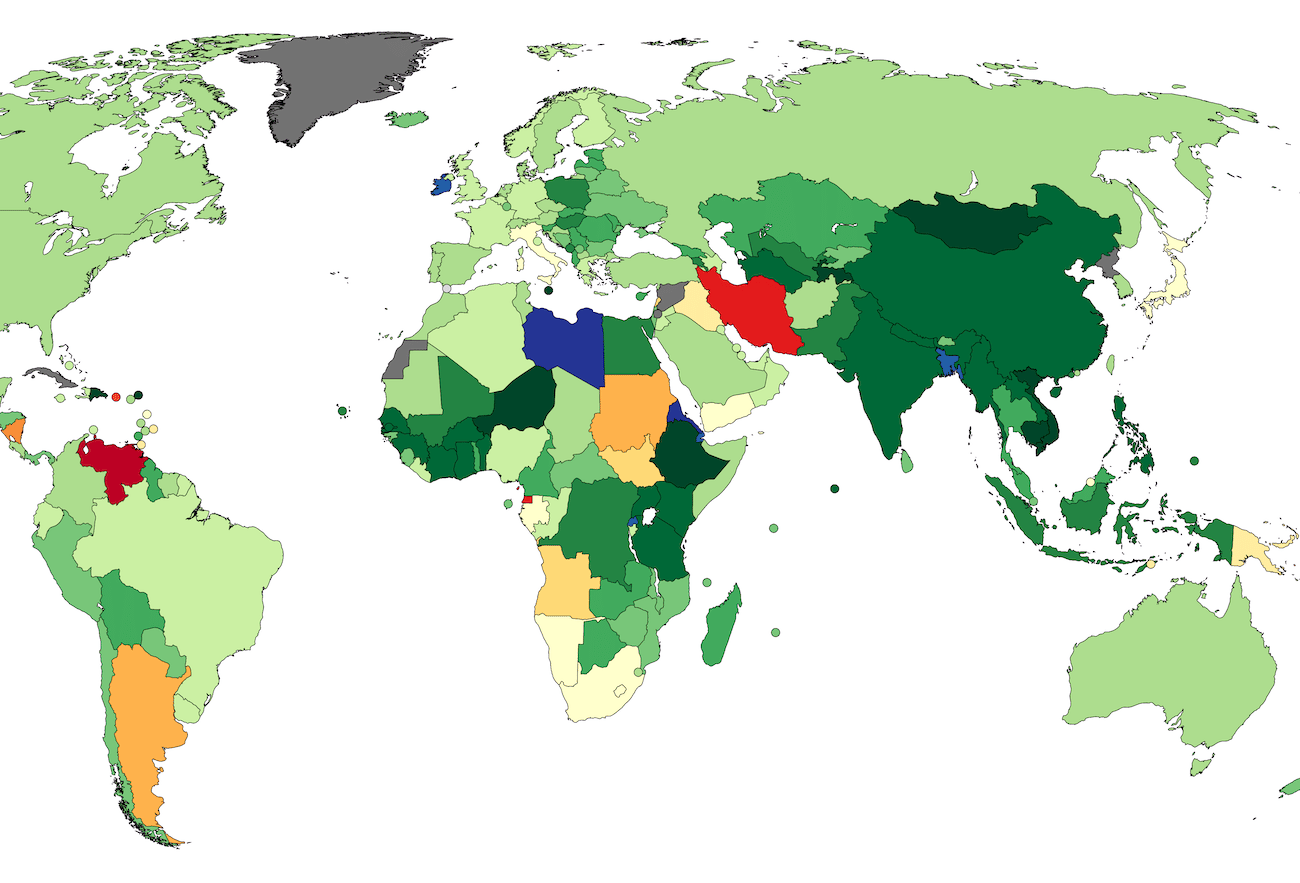

If Soper thinks too well of the past, she also says too little about inequality. She accepts that “economic growth will be needed in the short term to ensure the provision of basic needs in the poorest nations.” But many of Soper’s arguments apply only to the rich in the wealthiest countries, and especially the top 10 percent and richest 1 percent of the income distribution, whose carbon emissions have skyrocketed in the past two decades. They also apply to the top 10 percent and 1 percent of the rest of the world, which has also shown rapidly increasing carbon emissions. But work done by Lucas Chancel of the World Inequality Lab shows that per capita emissions from low- and middle-income groups in rich countries declined between 1990 and 2019. Since emissions are a reasonable proxy for other resource use as well, the data suggests that the very rich globally, not the rest of the society even in rich countries, are to blame for overconsumption.

Soper is right that consumerist aspirations are encouraged and even instigated by a global capitalist system designed to profit from them. But consumerism is not the only route to higher incomes. They also arise in the process of meeting minimum basic needs—those necessary to live with dignity and develop one’s human capability. For the greater part of the world’s population, these goals are still far away. A forthcoming book, Earth for All, from the Transformational Economics Commission of the Club of Rome (of which I am a member), highlights that only at income levels around $15,000 per capita could we create conditions necessary to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Incomes in about a hundred countries—many with large populations—fall well below that level. Increasing them would require not just time but a reversal of many of the current features of the global economic architecture and its economic power imbalances.

From a global perspective, then, some of Soper’s recommendations, while possibly applicable to many economic and social activities in rich countries, ring a little false. Capitalism surely drives people to work excessively and creates desires and fragilities that force them to work, but peasants across much of the world would find the idea of reducing the workweek laughable: nature does not allow for such luxury. And the unpaid women care workers across the world also cannot decide, in the absence of alternatives, simply to avoid such work or reduce the time they allocate to it.

No doubt Soper recognizes all this, and I am in complete agreement with her plea for “a politics of prosperity that dissociates pleasure and fulfilment from resource-intensive consumption.” I would simply argue for a more nuanced interpretation of that vision—one that takes into account the existence of sharp inequalities, looks at broader social goals for the economy rather than focusing on GDP, and takes seriously her own call to “to avoid fanciful assumptions about what would constitute globally sustainable forms of industry and lifestyle.”