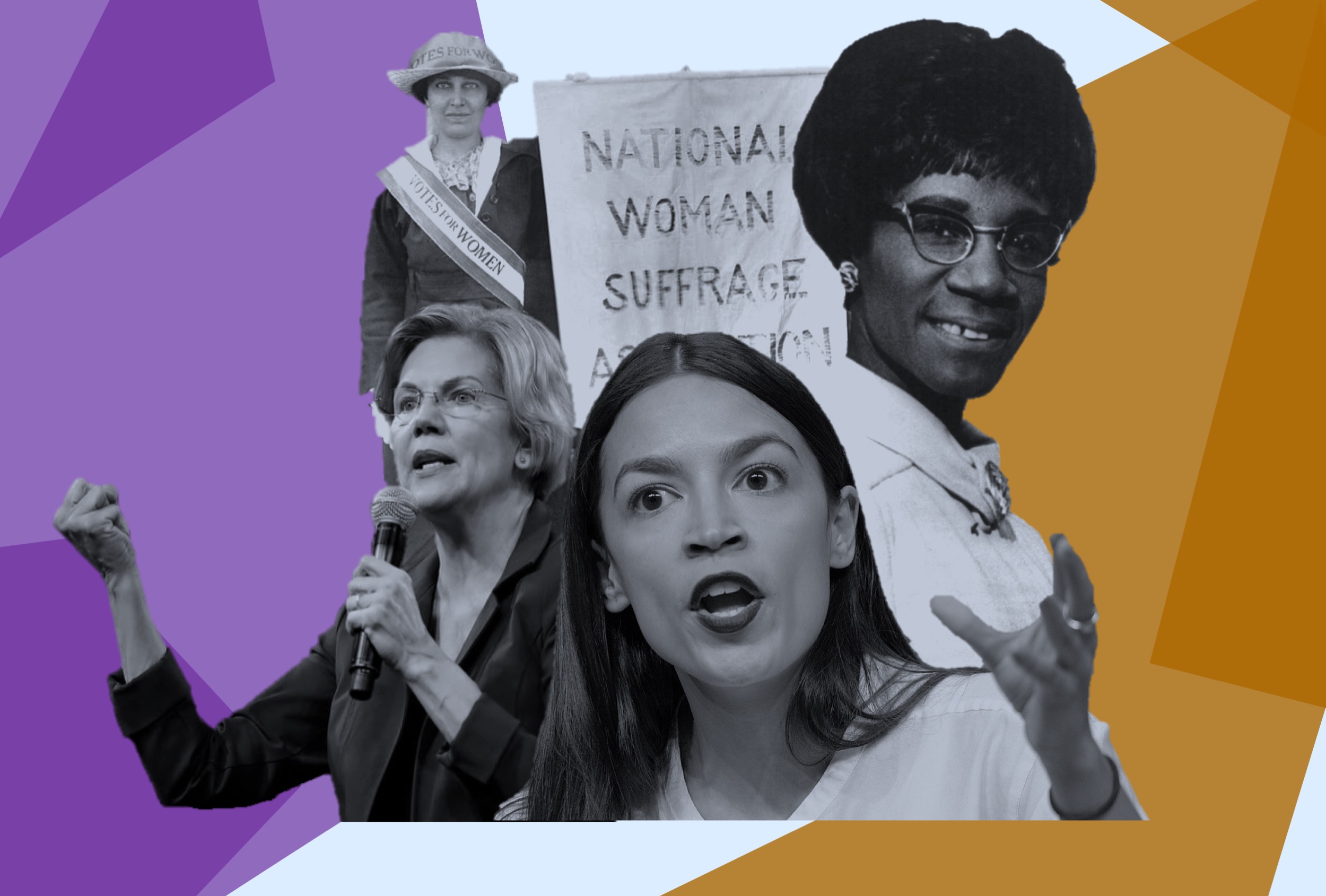

A hundred years ago, the United States became the eighteenth country to give white women the right to vote, an accomplishment that many Americans today look back on with pride. Yet within that club of early enfranchisers, the United States is one of only a few that has never elected a woman to its highest political office. Iceland and Norway have even elected women prime ministers more than once—Iceland in 1980 and 2017, and Norway in 1981 and 2013.

Indeed, as Jennifer Piscopo points out, the United States is far from being a leader when it comes to women holding elected offices, and I agree with her that women’s representation is the battle of this century. However, as a scholar of gender and politics, I am wary of overfocusing on the status of women in high executive offices and legislatures. The battle for women’s representation will be won or lost in our homes.

Early twentieth-century anti-suffrage arguments placed a striking emphasis on the domestic role reversals that would result if women were permitted to partake in politics. Political cartoons depicted hapless men holding naked, screaming babies while their wives went off to vote, or a suffragist’s house filled with unwashed clothes when her husband came home from work. If you give a woman the right to vote, these propaganda pieces suggested, she will probably ask you to pick up the kids from school, make your own dinner, and do the laundry before bed.

In response, suffragists went to great lengths to allay these fears. The scholarly literature on “maternalist” politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries highlights how women activists worked to convince men and hesitant women that the right to vote would not hinder but actually help women fulfill their roles in the private sphere. Far from inducing mothers to neglect their children or household duties, women’s suffrage would cultivate the civic virtues required for proper republican parenting, making mothers more capable of rearing the citizens of tomorrow.

By stressing the consistency of women’s suffrage with women’s caregiving as daughters, wives, and mothers, suffragists mobilized a broader subset of men and women than might have been possible with a more militant message. But maternalist politics did not disappear after the vote was won. On the contrary, the lines that suffragists strategically toed established limits that have proven difficult to overcome. “Women’s issues” in politics are still defined by the family, while issues of diplomacy, public finance, and security, among others, are still left to men.

For a while, this division was easier to maintain. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, for instance, women’s equal participation in politics was not generally incompatible with conventional gender roles in the household. Incomes were rising for many men, and many women could exit the workforce without endangering their families’ middle-class lives. To be sure, this was a privilege that many poor women and most women of color never enjoyed, but matters shifted for all women in the late 1980s, as men’s wages stagnated and the social safety net frayed, allowing families to fall into what Elizabeth Warren called the “two-income trap.”

When women at all income levels entered the workforce and stayed there, many feminists expected political gains would naturally follow. And, indeed, there were signs that the political terrain was changing. By 1980, as white men shifted toward the Republican party and white women began voting at the same rates as men, the first gender gap for the Democrats emerged. Within the Democratic Party, there were improvements in women’s representation at all levels of government.

But thirty years still separated Geraldine Ferraro’s failed vice-presidential bid from Hillary Clinton’s failed presidential run. And we know decisively that no woman will be at the helm in 2020. Moreover, women’s sustained roles in the economy have not fundamentally altered household dynamics. Forty years ago, Arlie Hochschild found that women who worked and earned substantially more than men did as great a share of housework as women who worked and earned substantially less—an observation that continues to hold true, as sociologists find that women today do far more in the household in every dimension.

So long as working women bear the brunt of the emotional, physical, and cognitive labor in the home, women will never have the intellectual space or the free time to participate fully in politics. Addressing this problem requires a combination of public policy and cultural change. We need excellent health care that is easy to understand, access, and pay for at minimum wage. We need well-funded daycare that is available not just during the hours of the white-collar workday but also when service workers are on the clock. We need a tax system that makes it easy to pay social security for domestic workers so that they too have access to retirement benefits in old age. We need no-exceptions rules for closing the gender pay gaps across all occupations. We need excellent family leave and sick leave that is socially mandated for all caregivers, especially men. And, as the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates, we need to acknowledge that many women are primary breadwinners and primary caregivers. In sum, representation begins by changing the rhythms and routines of the household for those who work in it. We must reform the household economy so that no one person or gender is primarily responsible for its maintenance.

Given the current political environment, with its backlash against women in power and resistance to increased diversity in many institutional settings, the prospect for women’s representation looks grim. In celebrating this centennial, it is high time to shuck off the maternalist impulses and fess up to what is really required to complete the suffragists’ dreams of political equality. Giving women more rights is not about making them better mothers, but about allowing them to be good at whatever they want to do with their lives.

Most importantly, those with privilege have to make the space for women to participate more fully in public life. Men need to be more than allies. They need to understand that fixing home life is not primarily women’s responsibility and then take up the mantle of improving family politics. Only then will democracy be freer for women, and only then will women finally be able to enter into the political world on equal terms.