The ancient Greek and Roman Stoics told prospective pupils a story about the hero Hercules. Arriving at a fork in the road, the young hero is approached by two goddesses. One is beautiful and tempting; she promises happiness and worldly renown. The other, named Virtue, tells him that her path involves hard work, risk, and suffering—and yet wisdom, justice, and courage will be their own rewards. The original hero was a thickheaded tough guy whose deeds belonged more to the world of pro wrestling than to the world of ideas. But the Stoics gave his story an intellectual spin, using it to proclaim the virtues of learning, study, and a type of philosophical ambition in which ideas are closely linked to political leadership. (The school produced two outstanding leaders, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, and heavily influenced countless others.)

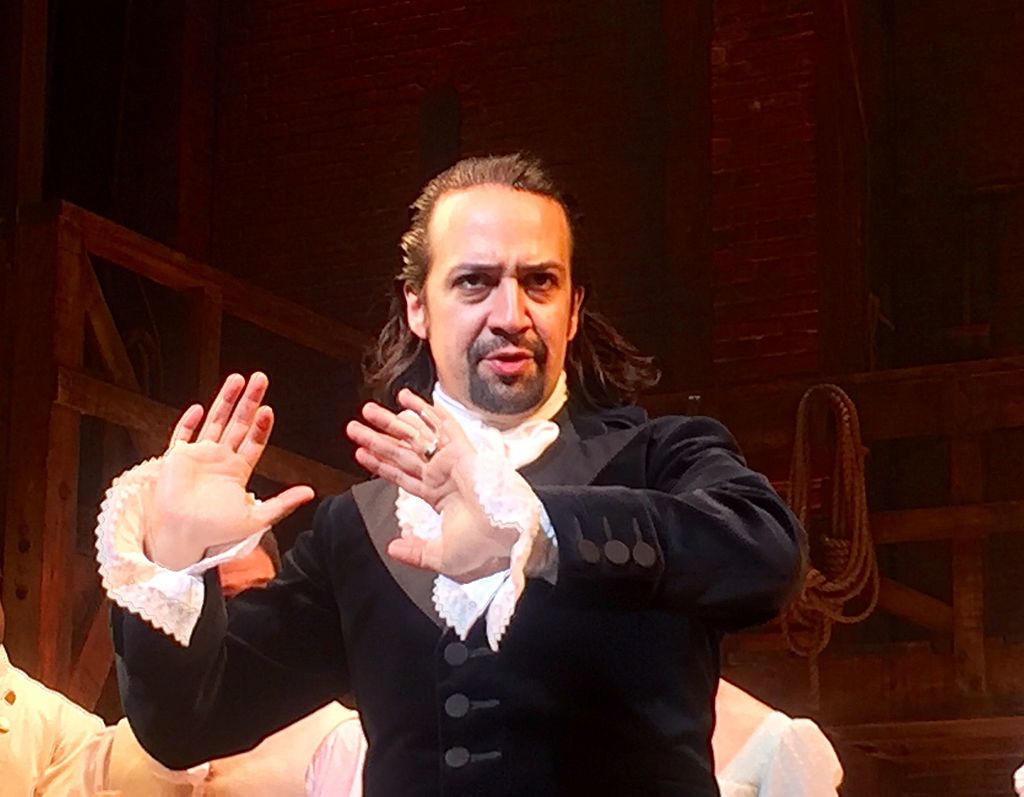

At its heart, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton is the Choice of Hercules, retold in a more subtle and compelling form, as a choice between two kinds of political life, one of service and another of positional preeminence. These types are represented in Miranda’s narrative by Hamilton and his associate and friend (to a point) Aaron Burr. Both lives involve an ambition for preeminence and a desire to make a difference. Neither is a life of indolence and profligate vice that makes the bad side in the myth such an obvious loser. Instead both choices are powerfully tempting to an aspiring politician, and to ambitious young people more generally. And how they choose makes a large difference both to their individual lives and to the lives of those they govern.

• • •

Closely following Ron Chernow’s excellent biography, Alexander Hamilton (2004), Miranda depicts Hamilton, the illegitimate West Indian, arriving in the future United States with huge ambition and drive. He makes an impression on George Washington, who makes him a confidant. During the Revolution Hamilton plays a military role, but he already shows a knack for nation-building. Known for his strong interest in women, he meets and marries the sweet-natured Eliza Schuyler, but is equally drawn to her more intellectual and high-spirited sister Angelica—and, reportedly, to quite a few others. After the victory at Yorktown, working alongside Washington, Hamilton helps to map out the nation’s institutional structure, especially focusing on a strong centralized economy. Writing a large proportion of The Federalist Papers, he galvanizes support for the Constitution. Washington chooses him to be the first Treasury secretary.

If you are not in the room where it happens, you cannot influence history’s course.

Aaron Burr, meanwhile, though highly capable, never quite manages to gain Washington’s trust. As a practicing lawyer, Burr can at times outdo Hamilton, but his lack of clear principles inhibits his political rise. When Hamilton helps broker a compromise with Jefferson and Madison about the location of the nation’s capital, over a famous dinner that only a select few attend, Burr is not included. Hamilton, meanwhile, makes a fatal misstep, falling into an extended sexual affair with the married Maria Reynolds, who, with her husband, blackmails him. When knowledge of the blackmail becomes public, Hamilton’s political adversaries initially think the payments are a sign of political corruption—until Hamilton, who seems to think that prolix writing can solve any problem, publishes a detailed, soul-baring pamphlet narrating the scandalous story, thus clearing himself from the charge of corruption but permanently barring himself from becoming president. The news also devastates his wife, who burns all the letters relating to the affair. A few years later, Hamilton’s beloved son dies in a duel defending his father’s honor. The election of 1800 leads to a deadlock between Burr and Jefferson. Hamilton throws his support behind Jefferson. A few years later, Burr, seething over his stalled career and blaming everything on Hamilton, challenges him to a duel. Hamilton, though abhorring the custom, accepts and is killed.

In Miranda’s version of the Choice of Hercules, one goddess whispers that preeminence and insider status are the only things that matter: you just have to be “in the room where it happens.” If you take this path, you still have to be smart, disciplined, and hard-working. But it may seem best not to have firm ideas or deep moral commitments, since it may be prudent to change course in accordance with prevailing fashion. That’s Burr, charismatic and immensely able, but unwilling to take a stand: “Don’t let them know what you’re against or what you’re for.” (To which Hamilton replies, “You can’t be serious.”)

The other goddess (who might be named George Washington) counsels that making a splash is easy, but creating something fine is difficult and risky. Political creation requires study, deliberation, maybe even philosophy! (All the framers read at least Locke and Montesquieu, but Hamilton read far more.) And it involves risk and suffering. The reward is that you may be able to create something that lives on after you.

The choice, in a sense, is Hamilton’s, but he really has made his choice from the start, and needs only minor course-correction from Washington. From his first entrance, he announces his aim to be both “a hero and a scholar,” reading “every treatise on the shelf.” And while Burr sings about his urgent desire to be inside that room, Hamilton sings, “I wanna build / something that’s / gonna / outlive me.”

Burr sees Hamilton as foolish: if you want preeminence and insider status, you should not put your cards on the table (or even have any cards). “Talk less! / Smile more!” Hamilton, for his part, simply cannot comprehend the emptiness at Burr’s core: “Burr, we studied and we fought and we killed / for the notion of a nation we now get to build. / For once in your life, take a stand with pride. / I don’t understand how you stand to the side.” When he decides to back Jefferson—a long-time rival whose principles he in some ways deplores—over Burr, a moral cipher, Hamilton explains, “Jefferson has beliefs, Burr has none.”

Hamilton is the Choice of Hercules retold as a choice between two kinds of political life.

Miranda thus vividly dramatizes two democratic possibilities: the life of virtue—which may yield honor and fame, if things work out—and the life of honor-seeking, in which virtue is a servant to fashion. The choice is much harder than the one that faced Hercules. The Greco-Roman moralists liked to say that the life of virtue involves no competition: the more the better, and the world is large enough for many to be at the top. Miranda endorses that idea up to a point: in the show’s final number, Burr acknowledges, with remorse, that “the world was wide enough for both Hamilton and me.” But Hamilton’s story makes it clear that things are more complicated: Hamilton’s creations can succeed only because he, too, is a relentless competitor. He is able to leave a “legacy” to posterity only because he gains preeminence (winning Washington’s regard and trust, for example).

While virtue may be its own reward, it is not sufficient for political creation. The aspiration to create something fine may be enough if you are trying to be virtuous in a family, or a religious community; but the minute you enter a realm where the wherewithal to do good is in short supply, you have to play Burr’s game, at least up to a point. Burr is not wrong: if you are not in the room where it happens, you cannot influence history’s course. And you do not get to be in the room without successful competition against others.

I said that the musical depicts two democratic political lives, and it is true that the choice it dramatizes occurs especially sharply in the political realm. But the musical clearly intends a more general point about ambition and competition. The minute one embarks upon a type of virtuous action that has employment or distinction or offices attached, creative and virtuous conduct become to some extent positional. In theory there can never be too many fine musicians or artists or composers or philosophers: but you have to be hired first, and you have to have support for the dissemination of your work. Maya Lin had to win a competition before she could build her vision of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Young musicians have to be hired before they can play before a public. Young philosophers have to compete for scarce positions, or else their creativity will be silenced.

Creative pursuits do not all involve the same degree of forced competition. Thus some women could succeed as poets or novelists even though the literary world was shaped by sexism, but they could not become orchestra conductors or sculptors—though even as solitary writers, they still faced external obstacles that Virginia Woolf famously described. Democratic politics is not a sui generis case, but it lies at an extreme: there is little possibility of creative action unless one is an insider, and no possibility of winning that status without competition for the favor of both the populace and its elected leaders. Competition need not compromise virtue, but it always introduces temptations: slander, shading the truth, and above all narcissism and lack of respect for others.

Moreover the drive for fame and public honor is probably an important ingredient in political creativity. At least we see that Hamilton’s genuine ardor for ideas is always accompanied, and probably energized, by a desire to make a splash, which propels him past many obstacles. A “bastard, orphan, son of a whore,” he has a thirst for success and recognition that accompanies and feeds his ardor for virtue and ideas: “I’m just like my country, / I’m young, scrappy and hungry.” To the extent that he eventually fails to achieve all he aims for (his failure to become president is emphasized), his failure is ascribed, in the play, to too much honest disclosure (as in his ill-judged pamphlet about his affair with Maria Reynolds) and too little Burr-like craft. He does indeed talk and write too much, and he thus gives his enemies the fodder they need to stop his rise. These acute insights complicate and deepen the mythic “choice.”

But the moral psychology of the two paths, shrewdly observed, nonetheless makes us see two profoundly distinct alternatives. Hamilton, like Shakespeare’s Othello, is proud and thirsty for honor, but almost entirely free of envy. (Othello is jealous, but, as we will see, that is a different emotion.) Burr, like Iago, is utterly consumed by envy, and the play makes a case that envy is a cancer in the body politic, one which we must resist individually and collectively.

The play argues that envy is a cancer in the body politic, one which we must resist individually and collectively.

Envy has threatened democracies from their beginnings. Under absolute monarchy, people’s possibilities were fixed and they might come to believe that fate, or divine justice, had placed them where they were. But a society that rejects fixed orders and destinies in favor of mobility and competition opens the door wide to envy the positional achievements of others. If envy is sufficiently widespread, it can eventually threaten political order, particularly when a society has committed itself to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

What, then, is envy? Envy is a painful emotion that focuses on the good fortune or advantages of others, comparing one’s own situation unfavorably to theirs. It involves a rival, and a good or goods the envier thinks very important; the envier is pained because the rival possesses those good things and she does not. Typically envy involves some type of hostility toward the fortunate rival: the envier wants what the rival has, and feels ill will toward the rival in consequence. Envy thus creates animosity and tension at the heart of society, and this may ultimately serve as an obstacle to collective achievement.

Envy is similar to jealousy: both involve hostility toward a rival with respect to the possession or enjoyment of a valued good. Jealousy, however, is typically about the fear of a specific loss (usually, though not always, a loss of personal attention or love). It focuses on protecting the self’s most cherished relationships. It can therefore often be satisfied, as when it becomes clear that the rival is no longer a competitor for the affections of the loved person, or was never a real competitor. Only pathological jealousy keeps inventing new and often imaginary rivals, and jealousy is not always pathological.

Envy, by contrast, is rarely satisfied because the goods on which it typically focuses (status, wealth, other positional and competitive goods) are unevenly distributed in all societies, and no person can be sure of being at all times “in the room where it happens.” Burr hates Hamilton not for any specific quality, but as someone who eclipses him and looms above him. Underlying the hatred is an obsessive focus on positional preeminence rather than genuine achievement. “The room where it happens” is an anthem of poisonous envy worthy of Iago. The fact that Burr is possibly the drama’s sexiest and most charismatic figure makes the poison seductive, as in real life it so often is.

Envy supplies the envier with a distorting prism through which to see the world, subtly falsifying the claims of virtue. Thus, in Washington’s support for Hamilton, Burr sees only cronyism and not substance: “It must be nice . . . to have Washington on your side.” Later Burr thinks Hamilton endorsed Jefferson “just to keep me from winning.” The envier’s gaze is fixed on relative position, and can’t quite see the intrinsic qualities of actions and policies. A green haze is thrown over everything.

In his discussion of envy in A Theory of Justice (1971), John Rawls mentions three conditions under which outbreaks of socially destructive envy are especially likely. First, there is a psychological condition: people “lack sure confidence in their own value and in their ability to do anything worthwhile.” Second, there is a social condition: many circumstances arise when this psychological condition is experienced as painful and humiliating because the conditions of social life make the discrepancies that give rise to envy highly visible. Third, the envious see their position as offering them no constructive alternative to mere hostility. The only relief they can envisage is to inflict pain on others.

Positional preeminence is essential to getting the chance to do anything fine, and to acquire preeminence you have to obey the rules of the positional game.

These conditions fit Miranda’s Burr to a T. Some emptiness at his core—a lack of confidence in his ability to do anything worthwhile—makes him obsessed with concealing his real self. For example, his idealization of his dead mother and his intense love of his daughter surface only in solitary moments, as do his moving observations about love. The conditions of social life in the new rough-and-tumble nation make everyone’s position precarious. (Miranda suggests that Burr’s awareness that his distinguished parents leave him a “legacy to protect” makes uncertainty all the more intolerable to him.) Rawls plausibly holds that a stable and decent political structure can mitigate envy, but when the structure itself is still being created, no such mitigation can be expected. As for alternatives to hostility, Burr, having attempted unsuccessfully to become close to Washington—and then having attempted electoral politics without gaining the top office—finds nothing to fall back on other than hate. Envy begins in something specific: the desire to be at one particular secret meeting, to be “in the room where it happened.” But quickly it expands and becomes global: “I’ve got to be in the room where it happens.”

But unlike the irredeemable Iago, Burr is no cardboard villain, and the musical gestures toward his emotional depth. Hamilton, brilliant political theorist of federalism and shrewd creator of policy, is a mess when it comes to women and love. He spurns Eliza’s vision of a modest life of love and devotion. He is an easy mark for Maria and James Reynolds. He may have slept with Eliza’s sister, Angelica. Never do we feel he has any insight into personal love. It is Burr who, having fallen in love with Theodosia Prevost (ten years his senior), sings the memorable lyric: “Love doesn’t discriminate / between the sinners / and the saints, / it takes and it takes and it takes / and we keep loving anyway.” Miranda omits Burr’s real-life rapacious lechery, but he probably does accurately depict Burr’s love for Theodosia, as he does Burr’s intense love for his daughter, also named Theodosia.

Burr exchanged thousands of letters with this daughter, whom he taught to ride and hunt, to understand mathematics, and to read Latin and Greek. They corresponded intensely even when he was close by, since he used letters as a way of supervising her education, as he implemented his ideas about the equal education of women. Burr’s wife died in 1794, and his daughter thereafter became his right-hand partner and hostess. He had many affairs with other women, but confided above all in her, even after her marriage in 1801 to a wealthy landowner and politician from South Carolina. Her death at sea in 1813 was a devastating loss. An early feminist, Burr kept a portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft on the wall of his study, and he introduced a bill for women’s suffrage in the New York legislature. Although these details are omitted from Miranda’s libretto, Burr’s general cast of mind with regard to women is accurately depicted, and in one song Miranda’s Burr even refers to his mother as a genius.

Of course, we do not need Miranda’s play to tell us that envy in the domain of politics can coexist with real love and creativity in the domain of women and family; and that dedicated political creativity can coexist (and frequently does) with emotional stupidity. Some of history’s greatest politicians have explicitly deplored their deficiencies as husbands and family men (Nehru and Mandela are two moving examples). And those are the ones who had the emotional maturity to value love and thus to understand their own lack.

The climax of Miranda’s musical is the famous duel between Hamilton and Burr. Basically following history, Burr writes a provocative letter alluding to insults by Hamilton against his honor. Hamilton, far from seeking accommodation or offering apology—common escape options offered by the code of honor—writes back detailing a list of criticisms he has made and is willing to make once again:

Mr. Vice President,

I am not the reason no one trusts you.

No one knows what you believe.

I will not equivocate on my opinion,

I have always worn it on my sleeve. . . .

Here’s an itemized list of thirty years of disagreements. . . .

Burr, your grievance is legitimate.

I stand by what I said, every bit of it.

You stand only for yourself.

It’s what you do.

I can’t apologize because it’s true.

Joanne Freeman argues in Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (2001) that the honor code in this period imposed highly stylized and rigid requirements on all gentlemen. If a person shirked these, he would be deprived of standing. Freeman seems to me to slight the Founders by failing to make my distinction between the honor one seeks through virtue and the honor one might, like Burr, seek as an end in itself. The Founders had all read Plato’s Republic, and all knew of the ring of Gyges, which challenged the person of virtue to endure even dishonor for virtue’s sake. They did not confuse virtue and honor. All knew, in principle, that virtue even without honor is superior to honor without virtue.

A “bastard, orphan, son of a whore,” Hamilton has a thirst for success that feeds his ardor.

Their more subtle problem was that politics has entrance conditions: as I have said, positional preeminence is essential to getting the chance to do anything fine, and to acquire preeminence you have to obey the rules of the positional game. That, at any rate, is how Hamilton clearly understood his choices.

Indeed, my one quarrel with Miranda is that, despite giving almost the entirety of Washington’s Farewell Address in the original words, he does not make room for (nor even paraphrase) a public statement Hamilton left in which he describes his reason for accepting Burr’s challenge, despite his opposition to dueling on religious and moral grounds. It concludes:

. . . all the considerations which constitute what men of the world denominate honor, impressed on me (as I thought) a peculiar necessity not to decline the call. The ability to be in future useful, whether in resisting mischief or effecting good, in those crises of our public affairs, which seem likely to happen, would probably be inseparable from a conformity with public prejudice in this particular.

Virtue, then, has conditions: in such a case as this, it might require putting one’s very life on the line. Hamilton explains that his solution to the dilemma is to accept the risk but “throw away my first shot,” that is, deliberately shoot off-target. Thus, ironically, the man whose zeal for work and virtuous action makes him repeatedly proclaim, near the opening of Miranda’s musical, “I am not throwing away my shot!” resolves to throw his shot away—which means, as it turns out, throwing away the chance to continue to act, work, and create.

So they meet with their seconds out in New Jersey, where anything goes. As virtue (in his view) required, Hamilton shoots in the air. Burr shoots to kill. A fascinating touch is that Burr is not thinking of hatred and envy at the crucial moment. Miranda imputes to him “only one thought, / This man will not make an orphan out of my daughter.” (There are multiple narratives of what actually happened, but it appears clear that Hamilton had resolved beforehand to shoot away from the mark, and that Burr, by contrast, had taken target practice before the event, and arrived at the dueling ground clad in a thick gabardine jacket that Chernow calls the eighteenth-century equivalent of a bulletproof vest. Whether Hamilton actually shot in the air or his pistol discharged involuntarily after he was hit—the two major possibilities—the asymmetry of intentions is clear.)

Neither hero is the naive Hercules of myth. Both are men of depth and complex political and personal ability. Burr makes his choice and Hamilton his, and Hamilton dies because his choice cannot be executed without outward conformity to the code of manly honor that is Burr’s only value. That is the hard thing about political leadership: you have to be two people and pursue two ends. But the moral of Miranda’s tale is clear: virtue and creativity are not just their own reward, they are ours. Dying, Hamilton sings, “I wrote some notes at the beginning of a song someone will sing for me.” And of course we are hearing it. Hamilton has prevailed because—orphan, immigrant, son of a whore—he offers a creative achievement that Miranda (and Ron Chernow before him) have found inspiring. Moreover Hamilton’s achievement in many respects is already in us and our lives: the Constitution, with all its flaws, and a national bank are apparently mundane matters that remain the backbone of our flawed yet still operating democracy.

Even Burr sees in the end that the zero-sum game of honor is stupid: “I should’ve known / the world was wide enough for both Hamilton and me.” And now his reward is to be remembered as “the villain in your history.” (I find this summation an all-too-tidy note in the musical, even though Burr did say exactly this, many years later, no doubt to make a good impression on somebody.)

Ultimately the choice of Hercules rests not on the stage but with Miranda’s audience, in a nation confused by the lure of fame and glitz and wary of intellectual work, a nation that prides itself on its preeminence but often delivers only hierarchy. It belongs, as well, to each young person choosing between reading and writing and easy popularity; to any person in any career that involves possibilities of both external honor and real creativity; to teenagers in our cities, where gangs offer a path to honor and influence that is seductive by contrast to the Hamiltonian life of self-education and self-reliance; to the immigrants and minorities so constantly referenced by the casting, who can make amazing contributions to a country that sorely needs their energy, if that country will only stop calling them names and if they are willing to tough it out and put up with adversity in order to do something fine; to aspiring artists, who can take either the path of fame or a path like Miranda’s (which included a liberal arts education at Wesleyan), a path that involves immense intellectual and historical work as well as extraordinary discipline and labor. As Washington would say: Envious detraction is easy, creating a good life is harder.