Blood of Victory

Random House, $24.95 (cloth)

Kingdom of Shadows

Random House, $24.95 (cloth)

Red Gold

Random House, $11.95 (paper)

The World at Night

Random House, $11.95 (paper)

The Polish Officer

Random House, $11.95 (paper)

Dark Star

Random House, $12.95 (paper)

Night Soldiers

Random House, $12.95 (paper)

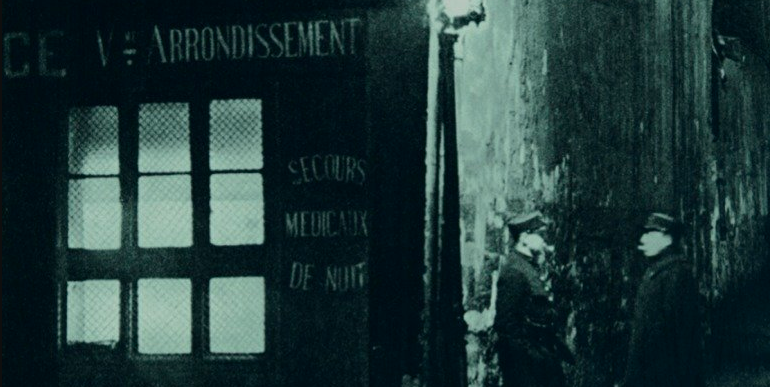

Alan Furst’s stylish entertainments, which he calls “historical spy novels,” are vivid snapshots of Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. His secret-agent plots are worthy successors to Graham Greene’s, and at their best his novels are serious works of moral fiction in the vein of Arthur Koestler or Joseph Conrad. But it is Furst’s brilliant atmosphere, especially in his romantic depictions of prewar Paris, that explains his growing appeal. His fiction evokes the melancholy of a lost world. His images and settings are suffused with the chiaroscuro of those Brassai photographs of 1930s Paris, in which thugs and apachesslouch in Montmartre cafés and streetlights glow dimly in the mist. (Furst’s publisher, Random House, acknowledges this affinity by using Brassai photos to make minor works of art of the book covers themselves.) For example, the opening paragraph of Kingdom of Shadows (2000) is pure Brassai in words:

On the tenth of March 1938, the night train from Budapest pulled into the Gare du Nord a little after four in the morning. There were storms in the Ruhr Valley and down through Picardy and the sides of the wagon-lits glistened with rain.

And you’re there, on the platform at the Gare du Nord on the tenth of March, 1938, squinting through the steam and fog and Gauloise smoke, rain-damp camelhair coat slung over your shoulders, the shadows of world-weariness and a thousand amorous nights under your eyes. Could anything be more romantic? Well, maybe the opening of Furst’s latest novel, Blood of Victory:

On 24 November, 1940, the first light of dawn found the Bulgarian ore freighter Svistov pounding through the Black Sea swells, a long night’s journey from Odessa and bound for Istanbul. The writer I. A. Serebin, sleepless as always, left his cabin and stood at the rail, searched the horizon for a sign of the Turkish coast, found only a blood red streak in the eastern sky.

This is less Brassai, more Casablanca. We’re moved, even excited, but we also admire from a safe distance the beauty of the unreal, a beauty the past never possessed when it was the present. Furst resuscitates the Europe of economic depression, genocide, and mad dictators, and he subtly infuses it with the same spirit that underlies popular interest in such cultural phenomena as the Titanic, the Hindenburg, Habsburg Vienna, the British Raj, or Mallory on Everest—the glamour of the doomed.

It took Furst a while to find his way to his own corner of this glamorous, doomed world. His beginnings were neither. Born in New York City in 1941 of (in his words) “rather normal writing stock, New York Jewish boys who go to prep school and wind up in publishing houses or as writers,” he earned his B.A. at Oberlin College and soon began to travel abroad. His fascination with 1930s and 1940s Europe germinated during his stint in 1970 as a visiting professor at Montpellier University in the south of France. He also lived for long periods in Paris, where, he says, “the past is still available. I remember a blue neon sign in the Eleventh Arrondissement . . . that had possibly been there since the 1930s.” By the late 1970s and early 1980s he was working as a journalist and freelance writer (among other works, he published a biography of cookie entrepreneur Debbie Fields called One Smart Cookie). It was a living, but not a métier. Then in 1983 came the turning point: Esquire magazine sent him on assignment to Moscow.

“It was the day that the Korean airliner was shot down,” recalls Furst. “Moscow had this incredible, intense atmosphere of intrigue and darkness and secrecy.” The fear in people’s eyes “broke my heart,” he says. “I decided it would be a perfect place to write a spy novel,” he adds. “They can’t write it. I’ll write it for them.” Result: Night Soldiers,published in 1988. In his words, “I found my place in life. I had found the little thing I did.”

In the story of Khristo Stoianev, a Bulgarian émigré whose brother is kicked to death by a fascist gang, Night Soldiers clearly lays out the future themes of Furst’s fiction. It’s a powerful, ambitious debut, with echoes of Conrad’s Under Western Eyes and Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. Indeed, Koestler could have had Furst’s Khristo in mind when he said “the vast majority . . . who fell under the totalitarian spell were activated by unselfish motives, ready to accept the role of martyr or executioner, as the cause demanded.” (This included Koestler himself, until the Moscow Trials turned him into an anticommunist.) Indeed, Khristo Stoianev, at least in the beginning—and this distinguishes him from most of Furst’s other heroes—is driven by entirely unselfish motives. He wants to avenge his brother and help destroy fascism, so he signs up with the NKVD in the hope of playing his part to do both. For a time, he serves the Kremlin loyally. Then he is sent to Spain during the civil war and discovers, as did George Orwell in Homage to Catalonia,that his “comrades” have betrayed him. Well, it’s 1937, a good time to become an ex-communist, so Khristo defects and takes that exile’s highway, so well-traveled by Furst’s characters, to Paris, where he encounters the normal opposites of human behavior: further betrayal and cowardice, but compensatory courage and conviction too, the bittersweet ambiguity of life that is the hallmark of Furst’s fiction.

But nothing here was what it seemed. Even the gray stone of the buildings hid within itself a score of secret tints, to be revealed only by one momentary strand of light. At first, the tide of secrecy that rippled through the streets had made him tense and watchful, but in time he realized that in a city of clandestine passions everyone was a spy. Amours.Fleeting or eternally renewed, tender or cruel, a single sip or an endless bacchanal, they were the true life and business of the place where money was never enough and power always drained away . . .

Eventually Khristo’s loyalties dissolve into bitterness, and, bereft of idealism, he learns to put himself first. There’s a hollowness in his soul at the end, but as a character he rings no less true for that. OverallNight Soldiers paints an absorbing portrait of a man who loses his faith in a world gone mad.

Dark Star followed in 1991, by which time Furst’s characters were beginning to develop family resemblances. One such is André Szara, the hero of Dark Star. As a Jew, an intellectual, an outsider, and an exile at heart, he is literary kin to several other Furst characters—second cousin to Khristo Stoianev for one, as another disillusioned NKVD operative. But André is also a correspondent for Pravda, which enables him to travel around Europe when most of his compatriots are locked up, physically or metaphorically, back in Stalin’s Russia. Not having much choice in the matter, Szara goes along with his Kremlin bosses to the extent of becoming deputy director of the Paris branch of the Soviet overseas spy network, known as the Red Orchestra. Still he’s no apparatchik, and he hates having to parrot Moscow’s party line in his articles. But eventually, like all of Furst’s leading men, Szara survives where others have perished, thanks to native intelligence, a nose for danger, and street smarts. He keeps a low profile, or tries to. Of course, in 1937 his options are dwindling by the day, with Hitler firmly in control in Berlin and “the number one toiler” back home starting in on his big purges. Szara’s job becomes just trying to stay alive, no easy task when from one day to the next he might be a target for the Gestapo, or ordinary Jew-hunting Nazis (there’s one harrowing scene in a synagogue on Kristallnacht), or even his own side. And what cause does he ultimately espouse? For that matter, what cause does any of Furst’s main characters espouse? With a couple of exceptions, none. But when a Furst hero is asked to help make it possible for people to continue enjoying life without interference from the authorities, it’s an offer he can’t refuse.

Night Soldiers and Dark Star are outstanding period thrillers, written soon after Furst made the change from journeyman freelancer to noir novelist. Having grown more self-confident, Furst now sees Night Soldiers and Dark Star as “dense, resonant—too serious.” He has opted to streamline his work, like a chef forgoing heavy sauces for the sake of his waistline. Yet these two novels are somber and thought-provoking reading.

The Polish Officer came out next, in 1995, followed by The World at Night (1996), Red Gold (1999), Kingdom of Shadows (2000) and Blood of Victory. Regardless of the novels’ disparate locales and story lines, Furst’s work forms a multi-volume unity. After a while they read like a memoir written by a man whose name may be Khristo or Andre or Alexander or Nicholas, who may be Bulgarian or French or Polish or Hungarian or Russian, who is a cultured, somewhat cynical sensualist, a world-weary man of the world in whose heart some small spark of honor still smoulders . . . and who lives, at least part of the time, in Paris, Furst’s spiritual homeland and the main character of all his fiction. Not since the Lost Generation has an American author been so smitten with the City of Light. No matter where he transports his heroes, and they go all over the map—Budapest, Moscow, Sofia, Berlin, Warsaw, Geneva, Istanbul—Paris is the city through which all must pass, to which all must return. Furst is as possessed by it as is Rastignac in Balzac’s Old Goriot, to whom Paris is the great adversary (“henceforth there is war between us!” he declares in the final chapter, glaring down at the metropolis from the heights of Montmartre). To Furst, Paris is lover, mystery, and allure translated into stone, the heart of Europe, “the central magneto of the engine,” as he has called it. To his characters, too, it is a city of endless wonders. Here is Otto Adler, an anti-Nazi German émigré in Kingdom of Shadows, recently arrived in the French capital:

This would be his first full summer in France, it would find him poor and dreamy, passionate for dark, lovely corners—alleys and churches—full of schemes and opinions, in love with half the women he saw, depressed, amused, and impatient for lunch. In short, Parisian.

This is, of course, a very un-French reaction. No Parisian would be so sentimental.

But any number of foreigners would: Americans like Furst, for instance; or Germans, whose saying “God lives in France” (or “happy as God in France”—“Glücklich wie Gott in Frankreich”) comes up several times in the novels. And Paris lends itself to nostalgia more than most cities, because of its beauty, its self-knowledge, its character, its central place in French—therefore Western—civilization, and its well-preserved, largely nineteenth-century sense of order. Baron Haussmann and the Nazis notwithstanding, Paris is unchanging. So the City of Light is also the Eternal City, especially to a romantic like Furst, who revels in exploring every byway. Like Simenon in his Maigret novels, Furst has a sharp eye for the city’s seamy underside:

He went out to the Montrouge district, beyond the porte de Chatillon and the old cemetery, to the little factory streets around the rue Gabriel. . . . The nineteenth century; tiny cobbled streets shadowed by brick factory walls, huge rusted stacks with towers of brown smoke curling slowly into a dead sky. (The World at Night) To hell and gone up an endless hill in the back streets of Montmartre, a hotel two windows wide and six floors tall, the smell of the toilet in the hall good and strong on the fiery August day. (The Polish Officer)

But Furst also conveys the elegant, decadent delights of the prewar good life. One Hungarian character has his sauerkraut cooked not in beer but champagne. At the dinner parties thrown by an Austrian baroness, well-groomed men and fashionable women “spoke the Austrian dialect with High German flourishes, Hungarian and French, shifting effortlessly between languages when only a very particular expression would say what they meant.” In fact, few of Furst’s Parisians are real Parisians. Most are Central and Eastern European exiles.

One who is not, however, is Jean-Claude Casson, hero of the hauntingly titled The World at Night. He’s the genuine article, a born-and-bred Parisian, a womanizing libertine from the posh Sixteenth Arrondissement, and a second-rate film producer with several mediocre films to his credit. At the beginning of The World at Night, however, he’s about to have his first real success, a movie called Hotel Dorado. Its star is the irresistible Citrine, with whom he’s in love, or rather lust (a necessary subplot in all Furst’s fiction), and the cameras are set to roll. But the Nazis ruin his plans as well as those of millions of others by neatly sidestepping the mighty French Army and goose-stepping into Paris under the golden skies of June, 1940.

As Casson watched, the country died. He saw a granary looted, a farmhouse burned by men in a truck, a crowd of prisoners in gray behind barbed wire. “We’ll all live deep down, now,” the sculptor said, throwing a stick of wood on the fire. “Twenty ways to prepare a crayfish. Or, you know, chess. Sanskrit poetry. It will hurt like hell, sonny, you’ll see.”

In this novel as in the others, Furst’s action plays out on an existentialist stage. Like Camus, Furst burdens his hero with a colossal moral dilemma seemingly beyond his abilities to resolve. We watch fascinated as that character squirms his way through to a moral victory of sorts, then we give him a half hearted two cheers for just surviving. Casson is an even more reluctant hero than most of his colleagues in Furst’s fiction, but now that his beloved native city is overrun by the Wehrmacht and crawling with repulsive local collaborators, even he develops a sense of purpose, if not duty. He becomes involved in an elaborate espionage shell game with various freelancers, opportunists, German agents, and the British Secret Service. He makes futile secret trips to Spain and to the French countryside and nearly gets killed for his pains. Finally he risks everything on a perilous chance to score against the Nazis by agreeing to work for the British as a double agent, and his life turns almost literally into a minefield. But Casson redeems his honor and lives to fight again another day.

That day dawns grayly in Red Gold, the sequel to The World at Night. A year later, alive but down on his luck, Casson resembles Paris itself, also alive—just—but broken and depressed under the German yoke. It’s the chilly autumn of 1941, and Furst sketches the quiet despair of the great city with spooky veracity. After a farcical series of humiliations and a run-in with the authorities, Casson meets Degrave, a sympathetic gendarme who seeks to recruit him for a clandestine branch of de Gaulle’s Free French forces. Casson’s job would be to persuade the Communists, with their extensive network of contacts, to join in the crusade. It’s a hard assignment, but it’s not hard to win over a man like Casson.

“Tell me this, do you have a family? Are there people who depend on you?”

“No. I’m alone.”

“Well,” Degrave said. The word hung in the air, it meantthen what do you have to lose? “You can turn us down right away, or you can think it over. Personally, I’d appreciate your doing at least that.”

“All right.”

Degrave looked down. “The sad truth is,” he said quietly, “a country can’t survive unless people fight for it.”

“I know.”

“You’ll think it over, then. Take an hour. More, if you like.”

There was no point in waiting an hour. He took the job; he didn’t have it in his heart to refuse.

Nor do any of Furst’s heroes, when the moment comes. They’re not bad men, nor particularly good ones, either; they just don’t have anything better or more compelling to do. Except perhaps (at first) Khristo Stoianev in Night Soldiers and Nicolas Morath, hero of Kingdom of Shadows.

Morath has a country to fight for: Hungary. A playboy, heir to a title, man-about-town (Paris, of course), he’s recruited by his uncle, the Count Polanyi, an anti-Nazi master spy <0x00E0> ses heures, to go on a mission for the Shadow Front, a liberal group trying to rescue Hungary from the pro-Nazi Arrow Guard. Patriotic Morath is on board from the start, unlike Jean-Claude Casson; but like Casson, Morath is a neophyte in the espionage game, and he starts his mission on a farcical note with a few dead-end trips to his discredit before he hits his stride, at which point his travels take him into the grim heart of Central Europe where—to judge by its central location on the map of his world—Furst’s heart dwells when it’s not in Paris. Eventually, in the shadowy forests of that remote region, Morath pulls off a bit of a coup, thanks in large part to the efforts of a Mitteleurop<0x00E4>ischer Laurel-and-Hardy pair, Szubl and Mitten, who are probably Furst’s most successful comic—or tragicomic—creations.

Morath got there early, Wolfi Szubl was waiting for him. A heavy man, fifty or so, with a long, lugubrious face and red-rimmed eyes and a back bent by years of carrying sample cases of ladies’ foundation garments to every town in Mitteleuropa. Szubl was a blend of nationalities—he never said exactly which ones they were. Herbert Mitten was a Transylvanian Jew, born in Cluj when it was still in Hungary. Their papers, and their lives, were like dead leaves of the old empire, for years blown aimlessly up and down the streets of a dozen cities.

These two characters could have stepped straight out of a story by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

But Furst’s world, absurd and glamorous as it may be, is also the doom-filled world of the NKVD, the Gestapo, and mass murder, and he never lets us forget it. As mentioned in the opening paragraph quoted at the beginning of this article, his new novel Blood of Victory starts in November 1940, with Hitler apparently well on his way to world conquest. The Russian writer I. A. Serebin (note the accurate Russian style of address, initials used for name and patronymic: V. I. Lenin, L. N. Tolstoy) is arriving in Istanbul aboard a Bulgarian freighter. Ostensibly representing an émigré Russian organization based in now-occupied Paris, Serebin in fact represents nothing but himself. Naturally, he loves women and Paris (“When France fell . . . that day I was Parisian, more than I’d ever been”) and the good life, and as a typical Furstian exile he is a man without a nation, a wanderer, a “rootless cosmopolitan.” Indeed, he is also of Jewish ancestry, as are many of Furst’s characters, as if to heighten their sensitivity to the ambient dangers: “I’m a Jew, you see,” says a minor character in Blood, “and that’s quite out of fashion here.” Serebin has no army to enlist in, no state to swear allegiance to, no cause to fight for. He is falling between the cracks of existence. Then a hand reaches out and snatches him back into the world of the committed, for in the words of Leon Trotsky, “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” The saving, or damning, hand is that of Janos Polanyi, the Hungarian spymaster fromKingdom of Shadows. (The same characters appear and reappear throughout Furst’s recent novels, like relatives at a family gathering.) Polanyi is by now an ex-count, having renounced the title in favor of his nephew Nicolas. (“Can one be a former count?” inquires Serebin. “Oh, one can be anything,” says Polanyi.) Thus Serebin finds himself hired as a spy for an operation run at arm’s length by the British Secret Service. His mission: to disrupt Romanian oil supplies to Germany by scuttling barges in a shallow part of the Danube. Here’s where Furst’s historical research pays off, because it’s all true: Hitler did indeed covet Romania’s oil supplies, on which his armies were dependent, at least until, as expected, the Panzers overran Baku and secured oil supply lines from the Caspian oilfields; but the Führer still fully intended to guarantee the availability of Romanian oil to his armies. This is the backdrop to Serebin’s adventure as he sets off for Bucharest in the company of sexy, silky Marie-Galante, his mistress. Furst’s women tend to blur together after a while, but this one’s a real corker.

. . . she was stunning, glamorous. Exceptionally plucked, buffed and smoothed . . .

Aha! says the reader, recognizing the type. A Mata Hari! Well, maybe not. Furst has a few surprises up his sleeve, as does Marie-Galante.

Meanwhile, Romania itself is in a state of near-permanent civil war, a war within the greater war. All in all, it’s a tricky mission for a writer like Serebin, who is temperamentally more suited to discussion over vodka of the relative merits of the poet Babel (whose death is noted respectfully in passing, as other characters note elsewhere the death of the great Austrian writer Joseph Roth), the novelist Gorky, and sundry other literary compatriots. So he needs help, and he gets it from Ivan Kostyka, a wealthy Russian arms dealer, a newly minted baron (“But it was a Baltic barony, bought from an émigré Lithuanian, and bought in anger”) and apparent cynic of the type so invaluable in wartime dramas. Bogart’s Rick in Casablanca comes to mind. And like Rick—like all of Furst’s heroes, too, come to that—Kostyka is a cynic until faced with true idealism, at which point his cynicism falls apart and he makes a choice with which his creator clearly sympathizes; it’s a rare author who can sympathize with his villains. But in Furst’s writing it’s not always entirely clear who the real villains are. The spies on both sides are pretty louche characters, and espionage is portrayed as intimately bound up with military and business interests. All three are, in Furst’s view, well beyond the demands of mere morality.

More than in Furst’s other work, the spirit of Eric Ambler haunts these pages. Ambler’s Journey Into Fear also opens on a tramp steamer in the Mediterranean, circa 1940, and one of the main characters in hisBackground to Danger (1940), which is about an oil consortium that conspires to seize the Romanian oilfields, is an amoral cynic named Karidza who could be Baron Kostyka’s first cousin. But Ambler’s cynics are irredeemable, whereas Furst’s are usually amenable to a little persuasion.

The plot of Blood of Victory is a bit convoluted, and things take their time getting going, and the conversations, in trying to replicate the paranoia of the day, are somewhat too oblique (“Obliquity—the base element of a police state, learn it or die,” Serebin says to himself—a very perceptive insight, incidentally, into the workings of totalitarianism), but eventually the story cranks up and hurtles along at a speed that reminded me less of Eric Ambler and more of Tintin, another icon of the European 1930s and 1940s. (This is intended as a compliment. Tintin may be a comic-strip character, but in the atmospheric Balkan drama King Ottokar’s Sceptre, with its period villains like Müsstler, Rastapopoulos, and Colonel Sponsz, he’s at least as heroic as I. A. Serebin.) But in the end it doesn’t really matter if the action’s a bit overheated. C’est la guerre. That sensual, aromatic Balkan setting makes up for a lot, and the Romance here is so solidly shored up by History that nothing about Blood of Victory can be presumed to be entirely fictitious. Not even the title, taken from a speech given in 1918 by a French politician of such thoroughgoing obscurity that I can only shake my head in awe at Furst’s exhaustive research.

It is that historical accuracy, along with a deep romantic sensibility, that makes Furst’s bygone world such an irresistible retreat most of the time, when he keeps a firm rein on the plots and isn’t allowing himself to get carried away, as he so often does, by atmosphere. But whatatmosphere! His novels are as redolent of the thirties as a Montparnasse café is of Caporal smoke, and not only in his Paris scenes, although these are by far the best; he can also conjure up Istanbul, Sofia, Warsaw, and Moscow with an in-your-face immediacy. This is no mean feat for a contemporary American writer to pull off, even if the price of this literary legerdemain is sometimes a story line that meanders about a little, like a country cow path. And while I’m picking nits, I must add my opinion of Furst’s female characters. Not that women are given short shrift in Furst’s fiction. Indeed, they’re omnipresent.

Octavian met Serebin’s eyes in the rearview mirror and gave him an immensely oily and conspiratorial smile. Women, always women, only women. (Blood of Victory)

“Women, always women, only women” could be the battle cry of all of Furst’s male characters. Unfortunately, their consorts are interchangeable bits of crumpet fit only for the all-too-frequent rolls in the hay that come to seem perfunctory, even mechanical. There are exceptions: Marie-Galante in Blood of Victory, Mary Day in Kingdom of Shadows. But after a while I found myself taking the naughty parts as read and skipping ahead to the real story.

So Furst’s world is undoubtedly a man’s world. But the men, at least, fill the frame, and many of the characters—Khristo Stoianev, Count Polanyi, Andre Szara, the ruefully comic Szulc-Mitten duo—linger in the mind like fascinating people you met at that dinner party on the Avenue Montaigne, where the wine was flowing and the food was catered by Fouquet’s and all the women were beautiful.

Furst’s fiction focuses on the intersection of ordinary life and the epic horrors of World War II, and his growing popularity has helped him focus more on the sort of writer he wants to be. The kind of writer that is can be inferred from the fact that his own favorite novelist is not LeCarré, Graham Greene, or Koestler, but the elegant stylist Anthony Powell, author of that great roman-fleuve in twelve volumes, A Dance to the Music of Time. “I think he is the finest novelist of the twentieth century,” says Furst. “By a lot. Because he handles more things with more reserve and precision and with . . . beautiful, oblique, quiet, knife-edged perception.” The elegant restraint of Furst’s own prose, at its best, and the subtle allusions with which he fills his pages, shows how well he has learned that lesson.