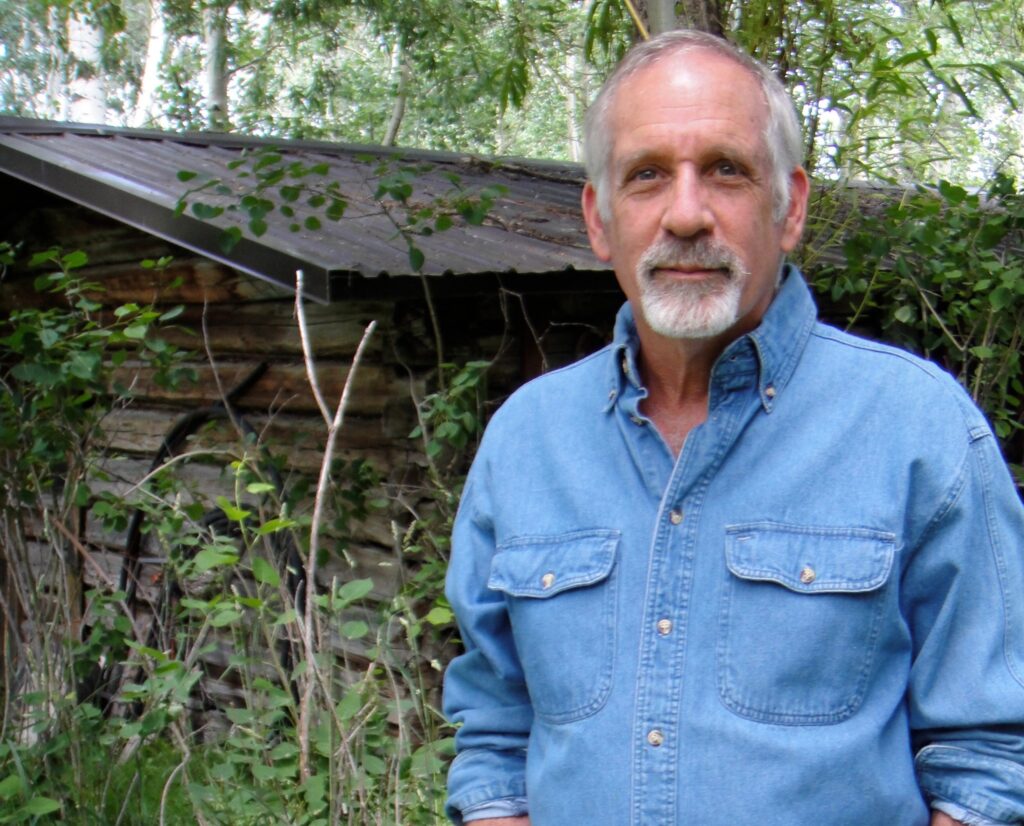

For a certain kind of American, Robert Stone exercises as large an influence as any contemporary writer. He is that rare bird in American letters who has managed to combine intellectual respectability (in the New York Review of Books, Al Alvarez admired his cultural sophistication, "full of sly quotes and literary references, strong on moral ambiguities") with a consistent popular readership. Stone straddles a transformative generational divide: between the benign paternalism of Eisenhower, when hipster culture was still largely underground, and the social explosions borne of the Vietnam war. His fiction expresses this historical transformation for many who also lived through it, and that accounts for much of his crossover appeal. In critical terms, he is often lumped with the "new neo-realists," such as Raymond Carver and Richard Ford. Stone also has his detractors, who typically complain about two characteristics of his work:the heavy influence of drugs (stemming from his days with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters) and his unabashedly violent and strung-out maleness.

All of these responses, to one degree or another, obscure his radical importance. For at the heart of Stone’s fiction is neither action-adventure nor philosophic challenge–though both are there–but a sustained exploration of a world of psychic delusion.

Stone himself touched on this in a 1985 interview with the Paris Review, when he said, "There are people who have delusional systems they are really quite aware of." He was speaking about the schizophrenic actress, Lu Anne, in his fourth novel Children of Light. In the course of that novel Lu Anne makes a critical decision: she will stop taking her medication in order to be in closer touch with herself as she works. By removing the pharmacological scrim that protects her from the dangerous core of her being, she surrenders to her delusions and knowingly risks madness. Among other things, Children of Light is about the consequence of Lu Anne’s decision. But Stone’s statement echoes far beyond that particular work.

Delusion, in his fictional world, is more than a symptom of madness–it is an essential condition of consciousness. We are fallen beings, fragmented souls, his novels suggest, and delusion, in its various forms, is our natural response to that condition. It is what we succumb to in our attempt to make ourselves coherent and whole. Like certain kinds of faith, with which it is curiously entwined, delusion offers two extreme alternatives: insanity and transcendence. The two aren’t mutually exclusive: Stone’s people wrestle with their delusions as demons, while simultaneously embracing them as guiding existential forces. In six novels, written over more than thirty years, he has explored this coexistence through the fractured lens of two recurring modern archetypes: the jaded intellectual hipster, and the violent sociopath. This exploration had taken Stone from the Civil Rights movement, through Vietnam, to Central America, and back to the contemporary United States in search of a moral and political response to our times.

• • •

Born in New York City in 1937, Stone grew up with his mother as an only child. Apparently he never met his father, who had been a railroad detective and worked on tugboats in New York harbor. By Stone’s own account, his upbringing was both eventful and scary. Like Lu Anne in Children of Light, his mother was schizophrenic. He calls it a case of "curious luck" to have been raised by her. It gave him, he says, "a tremendous advantage in understanding the relationship of language to reality … I had to sort out causality for myself." An unavoidable aspect of this upbringing, one may assume, was to internalize his mother’s delusions. If the mother was touched by fire, so was the child.

Her illness was severe enough to land her in a psychiatric hospital when Stone was six years old. With no other family to take him in, Stone went to live in an orphanage run by the Marist Brothers, a Catholic order on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He stayed with them for four years.

At seventeen, shortly after the Korean War, Stone served in the US Navy; then he married, moved from New York to New Orleans, and then to San Francisco, where he hooked up with Ken Kesey in the early days of his experiments with acid. Here, the relevant biographical data ends. But it is enough to give us a singularly American portrait: a boarder’s intimacy with two potent institutional cultures (the navy and the Catholic Church); a theologian’s preoccupation with apocalypse and faith; drugs, politics, violence, schizophrenia–these are the ingredients of Robert Stone’s America. His canvas is big, and his bias ideological in the sense that he tends to imbue his characters with an obsession with large ideas (God, political justice, moral necessity), then chronicles what occurs when these ideas collide with the fluctuant chaos of their psyches.

Despite the inherently surreal nature of his material–or perhaps because of it–Stone is a traditional writer. Each of his six novels employs an identical structure: an omniscient narrator shifts its focus among a handful of central characters in more or less alternating scenes. The structure is loose rather than stringent, functional rather than formalistic, and it serves Stone well (as it served Tolstoy, among other nineteenth-century masters) in that it allows him the wide aperture his material requires.

His literary forebears are equally as obvious. In his first novel, A Hall of Mirrors (1967), one encounters a dizzying gallery of influences: Dostoyevsky in its undisguised exploration of clashing ideas (one character is named Alyosha after the youngest brother Karamazov); Nelson Algren for its impressionistically gritty street life; pulp fiction in its reach for a kind of shorthand urgency. ("But even as he raised the water glass for the next bitter mule-whip thong of bourbon, the glittering Christmas-tree nostalgia had drained away into cold dark empty streets.") The broad caricaturing strokes to describe minor characters feel straight out of Dos Passos (one walk-on character has a "face like a lambchop"), and the inevitable echoes of Hemingway float in and out of the prose. ("She got out of bed and opened the sooty black shutters … the wind came against her face charged with blossoms and soft sunlight.") One sees the imprint of Mailer in Stone’s depiction of the hipster as a philosophical psychopath. And Ralph Ellison’s 1952 masterpiece Invisible Man casts a long shadow over A Hall of Mirrors both in what Ellison called "the politicization of hate," which is Mirrors’central theme, and in the cynically staged race riot that forms the climax of Mirrors, which is reminiscent of the melee near the end of Invisible Man.

Despite these derivations, A Hall of Mirrors’ central character, Rheinhardt, made clear the originality of Stone’s particular objective. A vision-haunted, alcoholic hipster, Rheinhardt washes up broke in New Orleans, and lands a job at a right-wing radio station whose purpose is to agitate its listeners into joining a violent race war. Though he sees through the nefarious plot, Rheinhardt has no qualms about supporting it. Where Mailer saw the hipster as an existential hero, Stone is in touch with his amoral derangement. Rheinhardt gladly takes the dough, and puts his considerable skills at the service of inciting the masses to evil. Imagine Kerouac during his finest improvisational days, dee-jaying for a radio station run by the Ku Klux Klan, and you’ll get the picture. (The image isn’t far-fetched–by the 1960s Kerouac was a self-described reactionary, with openly racist and anti-Semitic leanings.) Rheinhardt is a symptom of the larger psychosis, rather than the corrective to it postulated by Mailer in "The White Negro," or by Allen Ginsberg, later, as he carefully handled the public image of the Beats. Stone’s hipster is desperate, faithless, and dangerous–a strung out poet in love with the perverse:

Now that’s where I really live, [Rheinhardt] told himself, that’s where my heart’s balm flows. Perversion resolves what any number of other things cannot. Perversion is what makes the world, as they say, go round.

When one more altruistic (if not necessarily purer) than Rheinhardt tells him, "Your cool is cheap," Rheinhardt justifies his cynicism by invoking his own poisoned nights of terror. In the face of such demons, he suggests, there can’t be even the desire for redemption.

Stone’s great challenge is to enter his characters’ psychotic delusions and recreate them for his reader as accessible, experiential reality. The problems in his first book reveal the enormity of this challenge, and how much Stone would have to overcome in his later work to meet it. The paradox of his subject lies in the fact that the delusionary condition of his characters is, objectively speaking, one of incoherence. And A Hall of Mirrors is, unsurprisingly, marked by frequent incoherent jags:"Clarity and again clarity. A winter sky. The ornamentation is out to be slurred; each seed of ornamentation may be opened to reveal an ordered structure." The connective tissue of the narrative is made of hallucinatory stuff, so that much of the time the reader feels as if he is being told a dream whose private allusions he’ll never quite be able to understand. The inner experiences of the characters suffer from a flattening sameness–there is little nuance to be found in their extreme states of mind, and they tend to exist in a kind of visionary bardo, disembodied yet over-explained, lacking mystery and definition at the same time. But for all A Hall of Mirrors’ faults, the primal, clairsentient power of its author’s contact with a certain kind of American psychosis–the subculture of drugs and violence in which Rheinhardt lives–was impossible to ignore.

• • •

And it wasn't ignored. Mirrors won the 1968 Faulkner Foundation Award for a first novel, launching a career that Stone has had the good fortune to follow without any apparent artistic compromise. He is one of a handful of American novelists who has been able to build a body of work on his own terms–and at his own speed. Stone has never been one to rush his work; and seven years would pass before the publication of his second novel Dog Soldiers, which won the National Book Award for 1975.

The novel represents a quantum leap over his first book, especially in Stone’s ability to make coherent the delusional workings of his characters’ minds. The story is simple enough: a frayed playwright travels to Vietnam with the vague hope of finding material to jump start his stalled creative career. In the course of hanging around Saigon, the material doesn’t present itself, but the proposition to smuggle a couple of kilos of heroin does. Converse, as the writer is called, accepts the proposition, and enlists the help of Hicks, an old acquaintance from his days in the Marines. Converse offers Hicks twenty-five hundred bucks to be the mule. Hicks agrees and duly carries the dope back to America, where the deal predictably goes awry. Hicks takes off with the heroin (and with Converse’s drug-addicted wife) and the chase is on, through various California canyons, and finally to a mountaintop near the Mexican border where a classic Western-style showdown occurs.

In the juxtaposition of Hicks and Converse, Stone begins to tap into his richest imaginative vein, adding new elements to Rheinhardt, stripping away others, and splitting the result in two to create counterbalancing psyches who viscerally recognize in each other unexpressed and threatening sides of themselves. Converse is less strung-out than Rheinhardt, he’s less vicious and extreme, but they share the same amoral core–both are immune to any form of idealistic conviction. Converse may recognize idealism in others and even hold it in a certain esteem, he just has no inner capacity for it–it seems to him an existential lie. Here he is weighing his decision to get into the drug trade:

There were moral objections to children … being burned to death by jellied petroleum…. And there were moral objections to people spending their lives shooting scag. Everyone felt these things. Everyone must, or the value of human life would decline. It was important that the value of human life not decline.

But a few pages later Converse concludes that, the world being the way it is, "people are just naturally going to want to get high. So there … that’s the way it’s done. He had confronted a moral objection and overridden it. He could deal with these matters as well as anyone."

This is the opposite of Hicks, who possesses a naïve talent for conviction, a native capacity for high sentiment–and a psychopath’s understanding of violence. If power is the ability to will one’s delusion into reality, then for most of Dog Soldiers the power belongs to Hicks. With this character, Stone subverts the pulp formula he cagily employs: Hicks is the sociopath as action hero. He contemplates love and kills with spontaneous coldness. While Converse greedily measures his fear ("It was the basis of his life … the medium through which he perceived his own soul, the formula through which he could confirm his existence"), Hicks has none, functioning on animal sense, hope, and adrenaline. He is a repulsive creature–one would instinctively recoil from him. But in the end the reader wonders who is more barbaric: he who murders for a deluded idea of justice and love, or Converse, the stalled writer who put the death-dance in motion because "A small rush of admiration, desire, and apocalyptic religion [subverted] his common sense."

In the novel’s final pages, Hicks drags his bleeding body through a burnt landscape, still clutching his talismanic bag of scag. Stone plunges deep inside the experience of this death-walk. The groundwork of the novel, the complexity of the character, combine to give us access to the workings of Hicks’ mind; so that what was, to the reader, delusional incoherence in A Hall of Mirrors, is now excruciating clarity. We are disturbed by the human dimension of this homicidal psychopath; we even empathize with his twisted code of justice. The triumph ofDog Soldiers is that when Hicks finally dies, the reader feels a conflicting mixture of immense relief and mourning.

• • •

With a certain Biblical symmetry, seven years would pass before Stone published his third novel, A Flag for Sunrise (1981), his most daring work, and quite possibly the most politically complex American novel of the 1980s. The protagonist, Frank Holliwell, (an older, more nuanced version of Converse fromDog Soldiers) is a professor of anthropology at an East Coast University. Looking for something to jolt him out of the generic funk of his academic routine, he arranges to give a lecture at a university in Central America. On his way, he is approached by an old friend from his Jesuit high school days. The friend, who works for the CIA, wants Holliwell to do him a "favor" of the kind he occasionally used to perform when he was in "government service" in Vietnam: to check up on a Catholic mission at a remote harbor in the embattled country of "Tecan." The Church has attempted to close the mission, but the American nun and priest who run it have refused to return home.

Citing professional compunction, Holliwell rejects the assignment. But after he delivers his lecture–a comically disastrous tableau of cultural misapprehension and paranoia–he decides to go ahead and visit the mission on his own. Once there, he finds himself in the midst of an impending uprising that the CIA and various international corporate interests are doing their best to abort.

This may sound like the set up for a run-of-the-mill political thriller, but from its opening pages A Flag for Sunrise declares itself to be much more. Stone doesn’t settle for an impressionistic shorthand here, as he had when writing about Saigon in Dog Soldiers. The fictitious country of Tecan–an amalgam of Guatemala, Honduras, and pre-Sandinista Nicaragua–is superbly imagined. The instant Holliwell approaches the airline desk on his way down south, his senses are perked for his passage into a nether zone: "the brightly lit corners began to reek of poverty and revenge, the drawling Spanish in the general din to sound of false-bottomed laughter." When he describes a local painter as "an imitator of Orozco," Stone nails the dwarfed cultural position of his tiny Central American pastiche. And of Tecan’s "malignant" volcanoes (into whose mouths, from other contexts, we know the bodies of so many dissenters have been discarded) he writes:

They rose solitary out of featureless tableland, bare, without harmony, unbeautiful enough to appear exactly what they were–burst excrescences on Tecan’s pocked dusty hide…. They communicated a troubling sense of the earth as nothing more than itself, of blind force and mortality. As mindlessly refuting of hope as a skull and bones. The landscape was a memento mori, the view ahead like a dead ocean floor.

In addition to his usual collection of variously exiled Americans, Stone presents an ambitious range of Central American figures. It’s a risky move, and it pays off, texturing the novel while extending its scope to a degree that none of his other work achieves. The character portraits are dead on–especially that of Oscar Ocampo, Holliwell’s Central American colleague. An academic with leftist sympathies, Ocampo is destroyed by a sexual indiscretion, then bought off by the CIA, and ultimately murdered. Here Stone captures the nightmare of being a precariously privileged intellectual in a country where disaffiliation is an impossible luxury. The landscape of Ocampo’s dream-life is so thoroughly stunted as to permit only a grotesque sentimentality by way of compensation. In the United States he would be a teacher with an inviolable private life like any other. In Central America he is doomed.

Stone’s banana republic, with its contradictions and tragic ironies, is unlike anything since V. S. Naipaul conjured Uganda in A Bend in the River.Indeed, for all their circumstantial differences, Holliwell shares an underlying sensibility with Naipaul’s narrator. Both are witnesses to a social atrocity to which they know there is no solution. Holliwell is "without beliefs, without hope–either for himself or for the world. Almost without friends, certainly without allies. Alone." In Tecan, he knows he is in the presence of evil–"an invisible shadow, a silence within a silence … a cold stone on the heart." And like Naipaul, Stone offers no softening metaphorical comfort, instead forcing the reader to share the anxiety of his insights.

When he falls spontaneously in love with Justin, the American nun from the besieged mission, it is because she possesses what he can never have: faith in ultimate justice. In Justin, this faith manifests as a self-annihilating surrender to the suffering of others that is beyond argument or reason. This is delusion of a different, higher order–the delusion of religious redemption. Justin is no mystical ecstatic, but a hard-eyed Catholic martyr in the mold of Simone Weil. "It’ll kill her, [Holliwell] thought, drive her crazy. Her eyes were already clouding with sorrow and loss."

• • •

His prophecy proves correct. When the revolution comes–and fails–Justin is arrested and murdered by her Tecanean nemesis, a fervently Catholic and sexually deviant lieutenant. Holliwell, for all the quasi-heroics and near-betrayals of his love, is unable to save her. Among Justin’s final words to him are: "I don’t have your faith in despair. I can’t take comfort in it like you can." Except as an impotent witness, Holliwell’s presence in Tecan has had no practical impact. He has effected nothing. And he ends up at sea, fleeing Tecan with another lost archetypal American, Pablo Tabor.

Since we are in the world of Robert Stone, we are in the world of the psychopath, and Pablo Tabor, a free-lancing, amphetamine-crazed reject from the US Coast Guard sounds a major chord throughout A Flag for Sunrise. A variant of Hicks from Dog Soldiers, Pablo doesn’t have a pot to piss in, yet he regards the vistas of his life as limitless. He is the American wildcard and curse: loyal to no one, casually homicidal, and a firm believer in the delusion of his personal Manifest Destiny.

Afloat together in a tiny open boat on the burning equatorial sea, Holliwell and Pablo are in a poisoned embrace. In a sense, Stone’s first three novels had been leading up to this encounter. For Holliwell, it is like being marooned with the demon side of his soul. As he studies the contours of Pablo’s face, his overheated eyes:

It was like looking into some visceral nastiness, something foul. And somehow familiar…. It was as though he had been cornered after a lifelong chase by his personal devil. All his life, he thought, from childhood, the likes of Pablo had been in pursuit of him.

Pablo, for his part, feverish and wounded, with the spoils of murder in the form of a large diamond in his pocket, is convinced that his very survival is proof that he is divinely chosen. "You got to understand something," he tells Holliwell. "There’s a process and I’m in the middle of it. A lot of stuff I do is meant to be."

This delusion is Pablo’s weakness. Lost in its coils, he fails to realize that his seemingly benign shipmate is about to kill him. "I know you, [Holliwell] thought, watching Pablo. Should have known you. Know you of old." And he steals Pablo’s knife, plunges it past his ribs, and then rolls him overboard.

Holliwell has killed his nemesis, but he is far from redeemed. There is no catharsis here. All he has gained is the right to continue living–which under the circumstances is no joyous prize:

He had learned what empty places were in him. He had undertaken a little assay at the good fight and found that neither good nor fight was left to him. Instead of quitting while he was ahead, he had gone after life again and they had shown him life and made him eat it.

There are no answers in A Flag for Sunrise,only questions. There is no right or wrong, only degrees of wrong. In the face of this, Stone suggests, abiding faith may be the only admirable path. But such faith–a delusion like any other after all–is for most of us impossible. And for those who can attain it, it leads to violence and death just the same.

• • •

There is a moment in A Flag for Sunrise when Holliwell, in an exasperated attempt to explain himself to his foreign antagonists, says: "What’s best about my country is not exportable." Asked by the Paris Review to name some of America’s best non-exportables, Stone answered: "Idealism. A tradition of rectitude that … sometimes has been translated into government Enlightenment ideas written into the Constitution…. The whole tradition so wonderfully mythologized in John Ford’s Westerns."

In Outerbridge Reach (1992), Stone dramatizes this "tradition of rectitude" in the person of former naval officer Owen Browne. Owen is Stone’s straightest major character to date. Husband, father, honest salesman of pleasure yachts for a large corporation, he is unexpectedly presented with the opportunity to sail one of his company’s vessels in a solo race around the world. Owen seizes upon this as the chance to right the disappointments of his life, "a chance … to get a hold of things … to make it up"–to be, on his own terms, true to the heroic dreams of his youth.

The race will estrange him from his wife, put him in unwitting collusion with the corrupt motives of the corporation he works for, and turn him into a liar and a public relations pawn. On the other hand, it will allow him to discover the parameters of his courage–both physical and moral–in exactly the way in which he had yearned. Ultimately, Owen’s journey will lead him to the brink of clarity and madness. And in the end, betrayed by his own "unexportable" code, he will take his life in an actual suicide of honor–a rare event in life as in fiction.

In Stone’s perennial fictional equation, Ron Strickland–hired by Owen’s employer to invade his life for the purpose of making a documentary film–carries the load of the sociopath. Like Pablo and Hicks, Strickland has an enormous capacity for withstanding humiliation, and the patience to exact revenge–mainly through his ability to trap people with his camera and re- assemble them at the editing console. But Strickland is different from those others. His radar may be in search of enmity and contention, but as an artist his job is to pop the bubble of people’s delusions, and reveal "the difference between what [they] say they’re doing and what’s really going on." What distinguishes Strickland is his sense that he too may be deluded, that "his own insight might be the result of some minor mutation … that things had some aspect he could not perceive."

Strickland stands alone among Stone’s sociopaths for the depth of his self-awareness, just as Outerbridge Reach stands alone among Stone’s other work for the understated quality of its prose. The distracting, sensational flourishes of his earlier fiction are absent from this novel, as is his weakness for what he elsewhere calls "epiphenomenal jolts"–sudden and irrepressible existential insight. There is almost no direct violence in Outerbridge Reach, and the author’s fondness for pulp action is eschewed in favor of a more subdued, finely calibrated tone. More importantly, Stone here doesn’t treat his characters as the avatar of pre-formed ideas; Outerbridge Reach penetrates its characters by quieter more confident means. In some ways, the novel’s success can be measured by the masterful representation of Owen’s transformative dementia at sea. Utterly alone with his psyche, Owen faces the collapse of everything he had believed in, or believed himself to be. On the surface it seems that he has succumbed to delusion and madness at sea. But in fact he has faced the delusional quality of the very dream that had brought him to sea. Here is perhaps Stone’s finest expression of delusion as clarity. In existential terms, Owen has never been saner. Outerbridge Reachpossesses an underlying compassion that gives new dimension to his work.

By contrast, Stone’s most recent novel, Damascus Gate (1998), about millennial obsession in Jerusalem, is strangely disappointing. All the subjects that have engaged him are in place–religious salvation, doomed love, social justice in a politically embattled country–but somehow the novel feels bloodless. Though Stone rarely wrote about New York, the anarchic quick-changing rhythms of the city in the 1950s was always present in his work. When he described Saigon, New Orleans, or a Central American capital, one could feel the native New Yorker’s facility for chaos–a naturalness with the coexistence of seemingly unrelated realities. This facility should have served him well in Jerusalem, but instead the city exists as a series of street-names and landmarks that never take on a life of their own. The same is true of the novel’s sprawling cast of characters. Lost souls, they succumb to all the chimeric passions that have preoccupied Stone throughout his writing career, but somehow their search seems mechanical. For the first time, Stone seems removed from his characters’ delusions–they read like case studies in the so-called Jerusalem Syndrome, that state of mind that has given rise to so many apocalyptic cults in Israel. Stone has a thorough and impressive knowledge of these cults, but it feels like a connoisseur’s knowledge, a collector’s knowledge–it never quite makes that critical journey from intellectual concept to imagined reality. One has the sense, at moments, that the author himself is experiencing a kind of millennial exhaustion: he is too much the theologian inDamascus Gate, and too little the novelist.

• • •

Near the end of Damascus Gate one of the many believers says: "If we try we can make things the way they were. The way they were is the way they’re supposed to be." The spirit of that simple statement is Gnostic, which may well be the world-view closest to the heart of Stone’s work. The Gnostic myth is one of fundamental loss. In a great battle between good and evil, it says, the divine being was destroyed and we were created. Our sole purpose on earth is to reassemble that divine being, to undo that ruin, to make things "the way they were," because "the way they were is the way they’re supposed to be."

From this longing to re-assemble ourselves, his stories suggest, come our dramas and our delusions. They are sublime and they are dangerous, these delusions, they are what drive us forward and make us human. Time and again the fractured souls in Stone’s best novels reach out to each other for some impossible semblance of wholeness. This act is almost always predicated on delusions–whether they be the anarchic, hallucinatory delusions borne of addiction and madness, like Rheinhardt’s and Lu Anne’s; or those borne of faith, like Justin’s; or grandiosity, like Pablo’s; or heroic honor, like Owen Browne’s; or love, like Holliwell’s and Hicks’. Very often they lead to death.

For more than thirty years, Stone has practiced an insistent, sometimes courageous, ability to enter his character’s psychoses, to take them into the narrative heart of his work and force the reader to live there. He wants you to feel as lost, as desperate, and as febrile as they, gasping for air under the untenable (and at times incommunicable) deluge of their ideas. When he fails at this, his work crashes up against the narrative shoals of incoherence. When he succeeds, it can be as powerfully experiential as an altered mind-state–a simulation of the delusional condition he so often describes.

But what is this condition?The dictionary defines delusion as "a belief held in spite of invalidating evidence." The definition may just as well apply to religious faith in redemption, or to political faith in absolute justice, and in Stone it often does. In his ambition to articulate the tragedy of this condition lies the largeness of Robert Stone’s fiction, and its accomplishment.