Loving Graham Greene

Gloria Emerson

Random House, $22.05 (cloth)

An American Outrage

G. K. Wuori

Algonquin $22.05 (cloth)

Look for the road to hell and you find it paved with good intentions. Look harder, and you begin to wonder: maybe the desire to do good–to live right by oneself and one’s fellows–can become hell itself.

Molly Benson, prime mover of Gloria Emerson’s novelLoving Graham Greene, knows nothing but good intentions. In trying to act on them, she creates unanticipated torments, some petty and some parlous, for people she wants to help. Married, childless, in her forties, Molly runs a small foundation out of her living room in Princeton, N.J. To the dismay of her friends, mother, and stockbroker, she can’t give her inherited money away fast enough to causes that irk the US government: "money for medicines in Cuba, money for the Sandinista tuberculosis clinics in Nicaragua, money for the rebel hospitals in El Salvador, money for Palestinians in Gaza, and so forth." Molly shares her taste for hot zones with her creator; Emerson won the National Book Award in 1978 forWinners & Losers, a study of the effects of the Vietnam War on Americans, and has spent time in and written about El Salvador, Gaza, and Algeria–all of which figure, in one way or another, in this novel.

Every angel of mercy needs a god to pray to; Molly’s is a writer:

Once, Molly tried to explain her devotion to Graham Greene to her mother. "He took sides," she said. "He was fearless." No one who heard this, and there were plenty of them, remembered or cared what all the sides once were but he always had. What he found indecent was the injustice that the poor of the world were in the habit of enduring, and the arrogance of the dictators and the bloated malevolent governments, so often propped up and pampered by the United States.

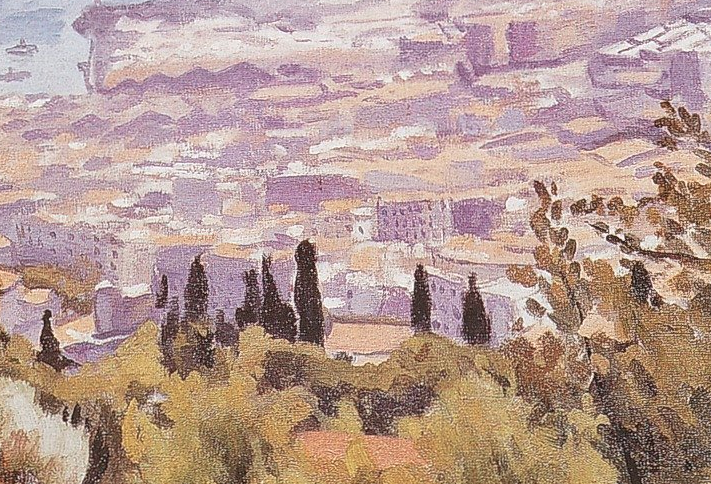

During his last years, Molly adopted Greene as a sort of pet project, barraging him with letters and clippings. On a trip to Antibes, where he kept a home, Molly encountered Greene himself and spent an afternoon making small-talk, an event she cherishes out of all proportion to its significance.

Molly also worships the memory of her brother, Harry, a journalist who shared her altruistic compulsions and was killed "in a small, ravaged country where Spanish was spoken." She needs to believe he was gunned down on purpose by a soldier; other journalists hint at something more useless and random, a heart attack at the wheel, a checkpoint fatally ignored. Harry understood why Molly "did not like money or trust its power"; he understood her "need to distance herself from a culture she abhorred, a society deformed and contaminated by money, sickening itself, insatiable and pathetic. No one could repudiate this except by abnegation, by sharing, and by a strict refusal to consume or to yield to any frivolity."

And yet Molly undertakes her good deeds in a whimsical–one could say frivolous–spirit, the moral equivalent of shopping sprees. From a catalog she orders "an inexpensive summer skirt" for a nun who, "unaccustomed to nice surprises," runs a feeding station in Central America. Undone by a photo of two murdered Salvadoran women, Molly "wanted to protest, but had only the feeblest idea of how to avenge the deaths of the two and honor them at the same time." She and Bertie, her childhood friend and do-good sidekick, stage an elaborate raid on the apartment of the Salvadoran consul general in New York: "the mission was to deface his front door with handprints in white paint, to scare the consul general to death…. ‘Mano Blanco,’ said Molly, remembering a bright red door with huge white hands on it, paint dripping. It was how the death squads in El Salvador announced that an assassination had been carried out in the house." But the consul general’s door turns out to be painted an unaccomodating beige, and the meager handprints the women plant on it might have been left there by "capricious children." Most of Molly’s projects turn out similar successes.

The central action in Loving Graham Greene kicks off after the writer’s death in 1991. As Molly grieves for him and for Harry, civil war looms in Algeria. To ease her pain and honor her hero, Molly conceives another of her schemes:

to lead a little delegation to Algiers in the hope of rescuing a few writers there…. A New York committee advised her, by mail and by telephone, that a growing number of Islamic fundamentalists there were threatening writers and journalists opposed to them. The committee only wanted money, but Molly thought she might locate a few doomed men and pay for their tickets to leave the country. This was a chance, too, to see the great colonial city the French had embraced for 132 years and relinquished in chaos and disgrace.

See the world while saving it.

That’s not absolutely fair to a good-hearted woman. Molly could easily be a figure of fun, an unquiet American bungling her way into places she can’t possibly understand. But Emerson’s heroine–and she is that–carries intelligence and dignity with her even as she wades into situations where her presence is worse than useless. When she sees two men she believes innocent being hauled into a police station in Algiers, "Molly, who passionately felt that all decent people must interfere to save the helpless even if it put them at risk, began hollering and running toward the group…. She was so fast that she was even able to grab the arm of one of the prisoners, as if to pull him free." That she only aggravates the police and makes a bad situation worse doesn’t wipe out the decency of the impulse. She superimposes extraordinary qualities on ordinary craven acts; she wants people to be better than they are, as well as better off. "What made Molly certain, although she had no experience in these matters, that the prisoners were innocent was their cringing appearance, the disbelief on their faces. She thought guilty men would be prouder and more defiant, carrying themselves differently to the beatings that would come and the long hours of interrogation ahead."

In the most basic sense, Molly isn’t naïve. She has read her Algerian history; she can identify the scars of torture; she suspects her own motives and the expeditions that are "clearly an escape to somewhere new, with desperate people as the excuse." She even knows that "her own version of Harry’s death could not hold up forever, however tightly she held on to it." But her flashes of self-awareness are just that; they spark for a moment and then go. Most of the time she runs at goals she can’t quite see. When adolescent Islamistes beat up her small party in the Casbah of Algiers, she flails and lashes out, a tornado of useless energy: "People came into the square, but only to watch. They found Molly entertaining before she collapsed. She urgently wanted to oppose the vicious boys, rather than just scream and crumple and bleed, as if something far greater were expected of her."

To show exactly where and how Molly fails, Emerson takes a surprising risk. Molly’s third-person-limited voice fills most of the story; but the narrative flits in and out of the consciousness of almost everyone who deals with her, often just stopping in for a quick thought or two: Why is this woman so weird? What does she want? Why can’t she live like normal people? When will she leave us alone? Can’t she see she’s causing trouble? That the risk pays off–that the reader can rotate smoothly through ten or twenty points of view in one slim book and hardly register the shifts–testifies to Emerson’s command of story, character and language. One catches shades of Greene in Emerson’s writing, which she keeps taut and smooth and yet flexible enough to wrap around a psychological detail or a telling moment in a glancing phrase or two–one of the many pleasures of a nearly perfect novel.

Loving Graham Greene is a beautifully controlled story about a woman unable to control the consequences of her acts; G. K. Wuori’s novel, An American Outrage, lets itself go from the beginning. It’s a blowsy, folksy, tragi-comic, catch-as-catch-can tale of lives gone off the rails in a small town in Maine. Quillifarkeag–Quilli, for short–has few claims to fame; it "has its basic streets and roads, its basic services. Its institutions consist of a few churches and schools, a branch of the state university, a modest hospital, and a good-sized potato-processing plant whose french fries you have eaten." (It also provided the setting for Wuori’s previous book, the story collection, Nude in Tub.)

The Virgil guiding us through Quilli’s circles of hell is Splotenbrun Doll, nicknamed Splotchy. (Wuori has a distracting weakness for extravagant names).

About me, a few things ought to be said, although the following account is not about me. That I am short, white-haired, middle-aged (a personal definition), divorced (for now), opinionated (thus: wordy, talky), educated, healthy, a newspaper reader, a book reader, and a little chubby are all tags that friends might hang on me if the question was, Who is Splotenbrun Doll? … There is another quality, however, another tag that is now properly mine, and as I write it here for the first time the door will open into this narrative, the beginnings of purpose will be seen: I am the father of a killer.

Splotchy has a devil of a tale to tell, and in the tradition of rural storytellers he takes his time telling it. What emerges, as he wanders through Quilli history, collecting bits and pieces of it from his fellow citizens, is this: after 26 years of seeming contentment, town resident Ellen DeLay left her husband, Joe, and like a latter-day eremite took up residence in a cabin in the woods, where she made a living by dressing hunters’ kill. She liked to do this scantily clothed, a habit that made cleanup easier and fueled the gossip back in town. Faced with the evidence–spousal abandonment, a life spent half-wild and half-naked in the woods–"Quilli, like any town, never cutting with a fine knife when a dull one will do, said Ellen went nuts."

In fact, Ellen seems to have been mostly sane, if unorthodox and confused about the best direction to pursue in life. (In some respects she’s kin to Molly Benson.) That doesn’t matter to the three men who, out drinking beer near Ellen’s woods, find themselves on the receiving end of a stray bullet fired from Ellen’s gun. (Nobody is seriously hurt.) Nor does it matter to the authorities, all women, all armed, who converge on the scene with uncertain motives and hair-trigger dispositions. One of them, town provost Cary Anderson, gets so itchy that she leads an assault on Ellen’s cabin. A personalized version of the Ruby Ridge or Waco sieges, it’s over in a flash, and Ellen’s dead, felled by dozens of rounds of ammunition– expelled from her oddball earthly paradise in a burst of apocalyptic frenzy. Wilma Doll, Splotchy’s forty-plus daughter and Ellen’s best pal, has the misfortune to be visiting Ellen during the assault. She escapes the barrage; she vows revenge, and in good unpremeditated time takes it.

Splotchy’s playing town Virgil at Wilma’s request, trying to beat fragments of memory into a narrative that sticks together and explains something. But Wuori can’t, or won’t, let Splotchy tell us certain things: why Cary "went nuts" at Ellen’s, why Ellen really left Joe (just that she felt something missing, a hollowness at the heart). It’s damn near impossible to decide whether this is deliberate–a way of saying that we can’t know what occupies the minds or controls the actions of other people–or whether Wuori’s characters leave him as baffled as they leave themselves.

Wuori’s characters have farcical, even demonic names–Splotchy, Vendrum Ponus, Fendamius "Poison" Gorelick, Spicy Pelletier–and they could lose a few aphorisms and quirks. But these people have more than a touch of the angel and the philosopher about them, and they know how to put deep feelings into fine words. Just because a place happens to be lowly, small, and inconsequential, Wuori seems to be saying, doesn’t mean that hellish tragedy can’t find it.