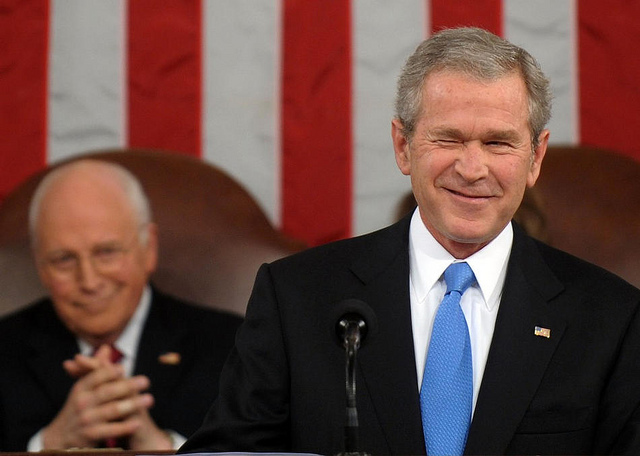

We have at the present time two government leaders, a president and a vice president, who, according to all available evidence, have carried out grave crimes. Will these two men leave office and live out their lives without being subjected to legal proceedings? Such proceedings will surely release new documents and provide additional testimony important in resolving their guilt or innocence. But the public record is now so elaborate, so detailed, and validated from so many directions that a weight is on the population’s shoulders: Does our already existing knowledge of what they have done obligate us to press for legal redress?

The question is painful even to ask, so painful that we may all yield to an easy temptation not to pursue it at all.

A major seduction away from prosecution is the euphoria that has surrounded the 2008 election campaign, even as the contest sharpens. “America at its Best” reads the front cover of the June 5, 2008, issue of The Economist, with a photograph of Barack Obama and John McCain pictured there. The elated sense that we might be restored to dignity in our own eyes and in the eyes of the world has rightly been credited first and foremost to Barack Obama, to his spiritual carriage, his open cadences, his refusal to degrade opponents or adversaries. But John McCain, too, is responsible for the atmosphere of well-being. Despite the large areas of overlap between his beliefs and those of George Bush, he has come before the electorate with a voice free of greed and cruelty. On countless occasions, he has spoken clearly about torture at a time when many other people have spoken confusedly.

This confidence in the power of the presidential nominees to restore us to ourselves is based above all on one attribute—not charisma, not eloquence, not heroism, but another quality that they share: their commitment to the rule of law. Since November will almost surely bring a return to the rule of law, why not devote our energies and full attention to the electoral process? To keep our eyes on the nominees is to be filled with renewed self-belief; to turn back to the current administration is to feel heartsick and ashamed. Why willingly look in one direction when one can look in the other?

First, because November will only “almost surely,” not surely, bring a return to the rule of law. Between now and November, any one of us could be taken ill, and so could one of the candidates. If John McCain suddenly became ill, for example, the Republican commitment to the rule of law would instantly cease to exist with clarion certainty. Anyone who doubts that a return to confusion is possible should be reminded that as late as this spring—when Bush vetoed a bill that outlawed the use of torture by the CIA—the Congress failed to achieve the two-thirds affirmative vote that would override the veto. The vote, like other congressional votes on torture, split along party lines. The pool of candidates committed to the rule of law is not deep: there are no back-up Republican candidates who have spoken out decisively against torture or the need to close Guantánamo. Moreover, McCain or Obama might lapse from law. Indeed, McCain—whose aggressive insistence on war with Iraq began within days of 9/11—voted with his party and President Bush on the CIA bill. McCain has consistently opposed making the federal courts available to detainees, and he condemned the recent Supreme Court decision ensuring habeas corpus protections for Guantánamo detainees as “one of the worst” in the country’s history.

Still, and this is a second reason to address the wrongdoing of the current administration, let us suppose what is fair to suppose, that Barack Obama and John McCain continue in good health, are as wedded to the law as they appear, that one of the two is elected fairly and honestly, and that the country begins its mighty pivot back to its gravitational center in the rule of law. It will be almost like a miracle cure, an overnight release from our eight-year-long affliction.

Or will it? What will this shift over to the rule of law mean? It will mean that when we are led by a person who does not believe in the rule of law, we will not as a country follow the rule of law; and when we are led by a person who does believe in the rule of law, we will follow the rule of law. If that is the case, the United States will continue to be what it has been during the last eight years: a country governed by the rule of men (their beliefs, their preferences, their choices), not by the rule of law (where beliefs, preferences, and choices are constrained by invariable and nonnegotiable prohibitions on cruelty and fraud). Just as one might in the past have said, “this president was short whereas the next president was tall” or “this president was isolationist whereas as the next president was internationalist,” so now one might shrug and say, “this president believed it was his prerogative to torture whereas the next president believed it was not.” The incalculable damage left by Bush and Cheney’s day-in-and-day-out contempt for national and international law includes the power to sweep forward in time and trivialize into a matter of personal preference any future president’s adherence to the law. Will we become a country in which the rule of law is just another policy preference? Do we really think that the rule of law is to be left in the hands of our leaders?

In deciding about legal redress, we need to be clear about the large stakes in our decision. The very multiplicity of the apparent crimes, the sheer array of arguably broken laws, is dizzying. But that multiplicity must be faced, for in it we will see that what got in President Bush’s way was not any one law but the rule of law itself. It is the rule of law that has been put in jeopardy by a project of executive domination; it is the rule of law that will continue to be in peril; and it is only, therefore, by addressing the crimes through legal instruments—through a formal, legal arena, and not simply through the electoral repudiation of bad policy—that the grave and widespread damage stands a chance of being repaired.

On March 4, 2008, the citizens of Brattleboro, Vermont, went to the polls and voted by a count of 2,012 to 1,795 to endorse the recommendation that if President Bush or Vice President Cheney came to that town, they should be “arrested and detained” for “crimes against our Constitution.” The citywide vote on Brattleboro’s non-binding resolution was the third step in a many-months-long process that scrupulously followed the procedures laid out in a section of the Brattleboro Town Charter entitled “Powers of the People.” In winter 2007 a petition (written and circulated by town resident Kurt Daims) was signed by the required 5 percent of the population. Then in January the Board of Selectman, by a three to two vote, forwarded the issue to the town-wide ballot scheduled for early spring.

How likely is it that President Bush or Vice President Cheney will visit Vermont, the single state in the country that George Bush has not entered in his first seven-and-a-half-years in office? Less likely, even, than it was before March 4. This still leaves a large geography in which the pair are at liberty.

Or does it? In the recent history of U.S. cities, one city often acts as the catalyst for hundreds of others: in January 2002, Ann Arbor, Michigan passed a resolution voicing its noncompliance with the Patriot Act; there are now 406 towns (and eight states) that have passed similar resolutions.1 So, too, the governing councils of ninety-two towns have, by a formal vote, called upon the U.S. Congress to begin impeachment proceedings against President Bush and Vice President Cheney.2 Perhaps not surprisingly, thirty-nine of those towns are in Vermont, twenty-one in Massachusetts; but the roll call of states represented includes California, Oregon, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Colorado, North Carolina, Maryland, Ohio, New Hampshire, and New York.

So far, only one other city has reenacted the Brattleboro arrest resolution. In a town meeting this past spring, Marlboro, Vermont voted 43 to 25 to draft and publish indictments of the country’s president and vice president, and “to arrest and detain” them should they arrive in town. But what if over the next two years the number of towns that formally vote to indict and arrest President Bush and Vice President Cheney steadily grows and eventually—as in the case of the town resolutions in favor of presidential impeachment or the resolutions against the Patriot Act—reaches the number 92 or 402? Cross-country travel will then become more restrictive for the former president and vice president. The felt-duty of the population to uphold the rule of law will be encoded in the geography of the country. These efforts provide a powerful historical record whether or not they result in a forcible assertion of the rule of law.

Can the harm done by Bush and Cheney be addressed through a more direct application of law? Vincent Bugliosi—who has successfully prosecuted twenty-one murder cases (most famously, Charles Manson) and eighty-four other felonies (losing only one case)—argues that Bush’s fabrications about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, connection to al Qaeda, and status as an imminent threat to the United States provide the legal basis for charging him with murder3 and trying him in any state that meets one condition: that it is the former residence of a soldier who has died in Iraq. All fifty states meet that condition. (A state-by-state list of the dead can be found at the Washington Post.) Early this summer, Bugliosi published a book outlining the argument for prosecution, forwarded a copy of the book to every state’s attorney general, and offered his assistance to any office that takes on the case.

Some of Bugliosi’s early chapters have the lurching rage of a grieving parent. (Most of us have a more anemic form of citizenship and can watch with poise as 4,000 twenty-year-olds die believing they are fighting the country that struck us on 9/11.) But the central chapters—on evidence, case law, jurisdiction, court arguments, and the lack of any exonerating defense—display a dispassionate, master prosecutor at work. Convinced that the defendant is guilty of mass murder and conspiracy to commit murder, this citizen means to win this case. Though each of the fifty states provides an appropriate venue, Bugliosi argues that a federal district court (the country has ninety-three) would be an even more appropriate site: Washington, D. C. heads the list. Prosecution can begin at any time after President Bush leaves office (he is immune while in office), and there is no statute of limitations.

As Bugliosi’s preference for a federal rather than a state venue suggests, the main domestic arena for addressing the administration’s aggressive dismantling of the rule of law is not individual citizen, town, or state, but the federal government: the Congress and the Supreme Court. The Senate’s recently released Report on Whether Public Statements Regarding Iraq by U.S. Government Officials Were Substantiated by Intelligence Information points in the same direction. While it does not make a case for murder prosecutions, it is nonetheless a devastating document, meticulous and relentless, that substantiates Bugliosi’s argument about culpable deceptions.

The Report takes five major policy statements about Iraq between late August 2002 and early February 2003—three speeches by President Bush, one by Vice President Cheney, one by Secretary of State Powell—and juxtaposes the information contained in specific sentences to the information available at the time from the intelligence community. It then draws on an array of other sentences spoken by top officials, including Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld and National Security Advisor Rice, and assesses their accuracy. This same sentence-by-sentence procedure is followed across eight categories: nuclear weapons, biological weapons, chemical weapons, weapons of mass destruction in general, weapons delivery systems, connections to terrorism, regime intent, and forecasts of post-war Iraq.

Two discrepancies are striking: between what the leaders of our country said about Iraq’s nuclear weapons and what the intelligence community believed at the time, and between what the leaders of our country said about Iraq’s connections to al Qaeda, before and after September 11, and what the intelligence community believed at the time.

The two subjects have a crucial effect on one another in creating the impression that Iraq poses an imminent nuclear threat to the United States. If Iraq has or is close to having a nuclear weapon but has no will to attack us, we remain in a safety zone: many countries have nuclear weapons; some of them, such as the United States, have thousands. If, conversely, Iraq is collaborating with al Qaeda but has no nuclear weapon (or other weapons of mass destruction), we once more remain in relative safety. Only if the two features are simultaneously present do we enter a high-alarm zone.

The two lies together proved to be much more potent than either one alone in building an alternative, extra-legal universe. The escalating use of the commander-in-chief clause to amplify presidential power is magnified once the country is fighting not a metaphorical war (a war on terror) but a literal war against another state, armed with weapons of mass destruction and ready to use them, perhaps by making them available to a proxy.

The virtuoso sentence-by-sentence Senate Report shows that the Bush administration starkly lied on the subject of Iraq’s collaboration with al Qaeda. The intelligence community repeatedly stated that they could find no reliable evidence of such a partnership: “Intelligence assessments, including multiple CIA reports and the November 2002 National Intelligence Estimate dismissed the claim that Iraq and al Qaeda were cooperating partners.”4 President Bush, in contrast, repeatedly announced that they worked together. “Al Qaeda hides, Saddam doesn’t, but the danger is, is that they work in concert. The danger is, is that al Qaeda becomes an extension of Saddam’s madness and his hatred and his capacity to extend weapons of mass destruction around the world. . . . [Y]ou can’t distinguish between al Qaeda and Saddam when you talk about the war on terror.”5

The intelligence community had noted a single source, Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, who spoke of Saddam Hussein providing al Qaeda with biological and chemical weapons training. But the intelligence reports on this information always stipulate that the man appears to be a fabricator.6 Once the war was underway, al-Libi—who had been renditioned to Egypt—acknowledged that he fabricated the information because he was threatened with (and was possibly subjected to) torture; only by giving the information his interrogators appeared to want, he alleges, could he stop the interrogation.7 According to Colin Powell’s chief of staff Lawrence Wilkerson, this misinformation played a decisive role in Powell’s willingness to make his UN speech, though he had no idea the information was elicited under coercion.8

The National Intelligence Estimate had noted that there was no intelligence indicating Iraq’s intention of supplying al Qaeda with any weapons of mass destruction. But this claim was repeatedly made by President Bush (“Iraq has longstanding ties to terrorist groups which are capable of, and willing to, deliver weapons of mass destruction”), Vice President Cheney (“[T]he war on terror will not be won ’till Iraq is completely and verifiably deprived of weapons of mass destruction”), and others such as Secretary of Defense Powell and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz.9 This constant assertion that al Qaeda and Iraq worked hand-in-hand made it possible for President Bush to announce in his March 17, 2003 “Address to the Nation” that “with the help of Iraq, the terrorists could fulfill their stated ambitions and kill thousands or hundreds of thousands of innocent people in our country.”10

The Senate Report shows that on the subject of Iraq’s nuclear weapon’s program President Bush and Vice President Cheney again fabricated, but this time not as starkly. Rather than issuing announcements that had no basis whatsoever in existing intelligence, they revised the intelligence community’s picture by exaggeration and omission.

One way to describe Iraq’s level of nuclear readiness is on a scale that goes from 1, where that country has no program at all for producing nuclear weapons, to 4, where it has an actual weapon in hand. Postwar intelligence would eventually certify that Iraq, in the months and years before the war began, was at level one, with no attempt underway to develop nuclear weapons, nor any programs to develop chemical or biological weapons. But prior to the war the intelligence reports were divided between level 1 and level 2. For example, in the fall of 2002 the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research stated its view that Iraq had no program for reconstituting nuclear weapons; the National Intelligence Estimate, in contrast, stated its belief that one was underway. No divided judgment, however, is registered in White House statements that instead used adrenalized constructions such as Dick Cheney’s “irrefutable evidence” and “absolutely devoted”: “We now have irrefutable evidence that he has . . . set up and reconstituted his program,” and “[w]e know he has been absolutely devoted to trying to acquire nuclear weapons. And we believe he has, in fact, reconstituted nuclear weapons.”11

A similar instance of division within the intelligence community that was translated into univocal certainty by the administration was over the subject of aluminum tubes. The CIA and the Department of Energy disagreed about whether aluminum tubes procured by Iraq were destined for nuclear weapons or instead the more benign purpose of rocket construction.12 President Bush and National Security Advisor Rice repeatedly cited the aluminum tubes, while never mentioning the disagreement.13

If the intelligence community said “no,” the administration said “maybe”; if the intelligence community said “maybe,” the administration said “certainly.” If the intelligence community said “long time,” the administration said “tomorrow.” For example, the intelligence community had repeatedly stated that even if Saddam Hussein had a weapons program, it would take 5 to 7 years to complete (with a caveat that if Iraq could acquire weapons parts from another country, the final product could be ready in 1 year). With the exception of Secretary of State Powell’s February 2003 speech to the United Nations, the 5-to-7 year window is simply never mentioned by anyone in the administration.14

The intelligence community assessments on nuclear weapons never strayed beyond level two. The Bush Administration, in contrast, started at level two and allowed them to slide up toward the highest zone of alarm. Insofar as the Bush administration acknowledged any uncertainty, they repositioned the site of it. Rather than locating the question mark (as the intelligence community had) at the boundary between “no interest in weapons development” and “attempts now underway at developing weapons,” they shifted the question mark to the line between “having the weapon” and “using the weapon.” “The first time we may be completely certain he has a—nuclear weapon is when, God forbids, he uses one,” President Bush announced in September of 2002.15 In the months that followed, President Bush would repeatedly sound the alarm: “Facing clear evidence of peril we cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.”16

The Senate Report contains a critical minority report from some Republican members of the Select Committee on Intelligence that, on close inspection, does nothing to weaken the majority report. For example, the minority report is at pains to show that members of Congress are themselves on record as having echoed the reckless statements about Iraq’s nuclear weapons.17 But far from exonerating President Bush, Vice President Cheney and Secretary of State Powell, the record of these statements by senators helps us comprehend why having leaders lie about highly classified information is devastating. A president’s words have, and should have, transmissible authority.18 It ought to be the case that a congressman or senator or citizen hearing the president’s statements can rely on the leader’s scrupulous accuracy and therefore repeat those words. A president’s words—that the country was conceived in liberty, that we have nothing to fear but fear itself, that we should guard against unwarranted influence by the military-industrial complex, that we should ask what we can do for our country—will, through repetition, eventually become part of the population’s own words; they will be dispersed throughout the verbal fabric of the country.19 The office of the presidency is a site of widespread emulation; that is why the act of violating that office by lying to Congress and the country about national security should be regarded as a high crime, thus meeting the Constitution’s standard for impeachment and removal. Perhaps the offense should be called not “Lying” but “Lying-While-Holding-an-Office-that-Will-Inspire-Millions-of-Repetitions-of-the-Lies and-Tens-of-Thousands-of-Deaths.”

Finally, the majority report, which is almost wholly dedicated to juxtaposing sentences spoken by the administration with sentences issued by the intelligence community, briefly notes two additional avenues of fabrication that appear to have been in play. First, various sectors of the intelligence community themselves were under White House pressure to come up with suitable answers. The question, then, is not just, did the White House exaggerate minimal information given by intelligence, but did the White House exaggerate minimal information that had itself been produced under pressure from the White House?20 Second, the White House has the power to declassify intelligence information selectively: President Bush released information that he wanted a wider readership to see and kept other intelligence (that presented an alternative or dissenting view) classified.21 The Senate Report directs attention to, but does not provide a sustained study of, the two problems.22

The President and his highest officers together erected a vast structure of lies about Iraq’s phantom nuclear partnership with al Qaeda. But is this latticework of lies itself a prosecutable crime? What is the crime? “Murder, conspiracy to commit murder, and aiding and assisting murder,” says Vincent Bugliosi, triable in either state or federal court. Others might say that the deceptions leading to war are “crimes against humanity” and “crimes against peace.” Still others think that impeachment and removal are the place to start.

On June 10, 2008, Congressmen Dennis Kucinich from Ohio and Robert Wexler from Florida cosponsored thirty-five articles of impeachment outlining the grounds for indicting George Bush. Included in the list of impeachable offenses are the President’s exaggerated fabrications about Iraq’s nuclear weapons; his direct lies about Iraq’s connections to al Qaeda; his retaliation against those who tried to tell the truth about the lack of nuclear weapons in Iraq, specifically his felonious disclosure of Valerie Plame Wilson’s clandestine CIA identity; his authorization and encouragement of torture as official policy; his direct responsibility for rendition; his illegal detention of “U.S. citizens and foreign captives” (including the “imprisonment of children”); his warrantless wiretapping; his failure to protect the United States by heeding pre-9/11 warnings; his failure to protect soldiers in Iraq with proper armor; his failure to protect the residents of New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina; his acts instructing subordinates to disregard congressional subpoenas; and his 1,100 signing statements releasing him from carrying out even those laws passed during his own administration. The House voted to forward the articles of impeachment to the Judiciary Committee. The articles of impeachment against George Bush are now side by side in the Judiciary Committee with articles of impeachment against Dick Cheney, first presented to the House of Representatives by Congressman Kucinich in the fall of 2007.

While the grounds of impeachment are appropriately numerous, and lying in the run-up to the Iraq War is one essential ground, it is crucial for the country to recognize that there is one crime with a legal profile so singular that it can—even standing alone—convey the wholesale contempt for the rule of law displayed by the Bush administration. That crime is the act of torture. The absolute prohibition on torture in national and international law, as Jeremy Waldron has argued in a recent article in Columbia Law Review, “epitomizes” the “spirit and genius of our law,” the prohibition “draw[s] a line between law and savagery,” it requires a “respect for human dignity” even when “law is at its most forceful and its subjects at their most vulnerable.” The absolute rule against torture is foundational and minimal: it is the bedrock on which the whole structure of law is erected. It is only “our clear grip on [this] well-known prohibition” that acts as a “crucial point of reference for sustaining . . . other less confident beliefs” about other prohibitions.23

The congressional articles of impeachment include “Authorizing, and Encouraging the Use of Torture.” Congress has begun to address the crime along other avenues of action that may remain independent from, or instead contribute to, the impeachment effort. Crucial to these efforts has been the research carried out by British barrister Philippe Sands and published in his 2008 book Torture Team: Rumsfeld’s Memo and the Betrayal of American Values. Sands’s essential point is that the pressure for torture originated in the White House, not—as the White House has tried to portray—among military interrogators at Guantánamo. Top attorneys—Attorney General Alberto Gonzales (then legal counsel for Bush), David Addington (legal counsel for Cheney), and William Haynes (legal counsel for Rumsfeld)—together visited Guantánamo with almost no other discernible purpose than to make clear to the military interrogators there how keenly the White House was awaiting whatever new information they could elicit.24

Sands’s Torture Team is not only a riveting book but a brilliantly designed and executed legal case with a series of witnesses for the prosecution taking the stand and together providing a set of damning revelations. Focused on the fifty-four consecutive days of torture inflicted on one particular prisoner, Mohammed al-Qahtani (a prisoner against whom all legal charges have recently been dropped), the case, by the very pressure of its single-mindedness, successfully shows that President Bush’s team was in direct contact with the room in which the physical injury was taking place. Sands shows not only that White House attorneys personally visited Guantánamo to convey the President, Vice President, and Secretary of Defense’s personal interest in “information” produced by the interrogations, but that between January 12 and January 15, 2003, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, who was under steady pressure from Navy General Counsel Alberto Mora to rescind the list of fifteen torture techniques that he, Rumsfeld, had personally authorized, was buying time. Rumsfeld hoped that in those additional seventy-two hours the continuing torture of al-Qahtani would at last yield the hoped-for information before he issued the order that the torture cease.

Did those interrogating al-Qahtani have a direct telephone line into Rumsfeld’s office during that last seventy-two hours? During the 1,296 hours of the full fifty-four days? That question and others will inevitably be asked during formal legal inquiries into White House torture either in Congress or in a courtroom.

Though focused on one prison and one prisoner, Sands’s book sets up an echo chamber in which years of revelations suddenly gather cumulative force. His book obligates us to remember all the instances of direct White House pressure that other investigatory reports have shown. For example, just as attorneys Gonzales, Addington, and Haynes personally visited Guantánamo, so a “senior member of the National Security Council” made a parallel visit to Abu Ghraib in November 2003.

Brigadier General Janis Karpinski described the visit to the authors of the 2004 Schlesinger Report, who summarized her words. The visit led “some personnel at the facility to conclude, perhaps incorrectly, that even the White House was interested in the intelligence gleaned from their interrogation reports.”25 In Brigadier General Karpinski’s August 3, 2005 interview with Jefferson Law School professor Marjorie Cohn, Karpinski revealed that posted on a pole at Abu Ghraib was a short list of interrogation techniques (including the use of dogs, stress positions, and lack of food) signed by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld with a handwritten postscript, “Make sure this happens!!”26 Top administration pressure for more “information” has also been described by former Pentagon lawyer Richard Schiffrin. Schiffrin, speaking to the New York Times on the eve of his June 2008 testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, stated that Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld’s lawyer William Haynes and others repeatedly “expressed ‘great frustration’ that the military was not effectively obtaining information from prisoners,” and complained that “the intelligence being obtained from detainees” was “insufficient.”27 These reports all indicate that the White House not only suspended the Geneva Conventions and signed the list of torture techniques, but personally leaned on the torturers to get ‘answers.’

In response to a report issued by the Inspector General in the Justice Department describing open debate at the White House about torture techniques, fifty-nine members of Congress have written a letter to the Justice Department urging the appointment of a special counsel to investigate whether President Bush and other high executive officers are guilty of crimes of torture.28 The Senate Armed Services Committee also requested that former Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld’s counsel, William Haynes (along with others) testify on the issue of interrogation practices in June 2008.29 And retired Major General Antonio Taguba, who authored one of the early studies of the abuse carried out by soldiers and military police at Abu Ghraib, has made public his assessment of the part played by the White House inner circle in formulating and promulgating a government policy of torture: “There is no longer any doubt as to whether the current administration has committed war crimes. The only question that remains to be answered is whether those who ordered the use of torture will be held to account.”30

Some hope for legal redress of the kind that Taguba calls for comes from the willingness of courts to resist presidential authority, as the very names of the leading Supreme Court cases indicate: Rasul v. Bush, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Boumediene v. Bush.

In Rasul v. Bush the court ruled 6 to 3 that detainees held at Guantánamo can challenge the legality of their detention in U.S. courts. Writing for the majority, Justice Stevens stressed that historically the writ of habeas corpus is, at its very core, “a means of reviewing the legality of Executive detention.”31 The fulcrum of the opinion is a passage in which he points out that the writ of habeas corpus “does not act upon the prisoner who seeks relief, but upon the person who holds him in what is alleged to be unlawful custody.”32 In other words, the question is not ‘Is Rasul within reach of the US courts?’ but ‘Is President Bush within reach of the United States courts?’ The answer to that question is yes. Justice Stevens closes the opinion by again stating that the issue is not whether foreign nationals and the zone of Guantánamo stand within the penumbra of the law but whether President Bush does: “What is presently at stake is only whether the federal courts have jurisdiction to determine the legality of the Executive’s potentially indefinite detention of individuals who claim to be wholly innocent of wrongdoing.”33 The answer, again: yes.

Two years later the Supreme Court examined the legitimacy of the military tribunals President Bush designed for Guantánamo, tribunals in which—as petitioner Salim Ahmed Hamdan complained—the accused is “excluded from his own trial.”34 The Court agreed: the tribunals violate what Justice Stevens, writing for the majority, identified as “the right to be present”—“one of the most fundamental protections.”35 A “glaring” feature of the tribunal design was its provision that the accused and his civilian counsel could be prohibited from hearing the evidence against him; a second feature was its inclusion of forms of evidence normally excluded—hearsay, information extracted by coercion, and testimony that was not sworn.36

The President’s tribunals, the Court ruled, are illegal. Their design lacks any legislative authorization and violates both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. In the earlier case, Rasul v. Bush, the Geneva accords had been repeatedly mentioned in the oral arguments (and twice referred to as “the supreme law of the land”) but had not been part of the decision itself.37 Now in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld Common Article 3 provided the foundation for the Court’s ruling. Among Common Article 3’s provisions is the requirement that a defendant be tried “by a regularly constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.” The requirement of a regularly constituted court is quoted 8 times by Justice Stevens and 13 times by Justice Kennedy in his concurring opinion.38

Responding to the President’s longstanding complaint that Geneva rules are vague, Justice Stevens observed that in order to accommodate many different legal systems, the Geneva Conventions are broad and flexible in their requirements. “But requirements they are nonetheless”.39 Justice Kennedy similarly stressed the meaning of the word “requirement.” When the United States ratified the Geneva Conventions, he noted, they became “binding law” in this country; moreover, he continued, as a result of Congress’s 1996 War Crimes Act, a violation of Common Article 3 is “a war crime.”40

In explaining what a “regularly constituted court” is, Justice Stevens and Justice Kennedy both invoked the definition given by the International Red Cross: a court “established and organized in accordance with the laws and procedures already in force in a country.”41 For detainees at Guantánamo, that would mean the court martial procedures established by the 1950 Uniform Code of Military Justice, or some other legislative base not yet provided by Congress.42 The executive branch contention that it would be “hamstrung” by the procedures of a military court martial is dismissed as insupportable by Justice Stevens who repeatedly faults the government for its “wholesale jettisoning of procedural protections.”43 Hamdan may (as the government argues) be extremely dangerous, concludes Justice Stevens, “but in undertaking to try Hamdan . . . the Executive is bound to comply with the Rule of Law.”44

Justice Kennedy comments on the odd necessity, apparently felt by Justice Stevens and him, to announce basic principles of international and national law (as though they were addressing a visitor from outer space), such as the fact just noted that following the rule of law is obligatory and that the legislative, executive, and judicial branches cannot act beyond the powers conferred on them by the Constitution.45 But the main rebuke to the executive is the stark invocation of the Geneva rules and the reminder that their violation constitutes a “war crime.” In January 2002 President Bush decided that Guantánamo detainees were not eligible for Geneva-rules protection; he later announced that he had the power to suspend them in Afghanistan but for the time being would not do so. In Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Court reminded the President and the American people that the Geneva rules had never ceased to be in effect, and that their violation is a war crime.

As the President’s mock-judicial schemes have been addressed and corrected in Rasul v. Bush and Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (as well as in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld and Boumediene v. Bush), it is to be hoped that the U.S. courts will eventually try President Bush for direct acts of licensing torture. A remarkable step in this direction took place on August 14, 2008, when a federal appeals court in New York agreed sua sponte (on their own initiative, without a request from either party) to rehear the rendition and torture case Arar v. Ashcroft. The court, presided over by 3 of its 12 judges, had earlier dismissed the case on national security grounds. Maher Arar—a Canadian citizen arrested at JFK airport without charge, held in solitary confinement for two weeks, flown to Syria where he was tortured, and imprisoned in a 3’ x 6’ x 7’ underground cell for a year—will have his case reheard by all twelve judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on December 9, 2008.

Some of the evidence for other torture cases may well come from the executive branch itself. Beginning in spring 2002, FBI agents in Afghanistan, who witnessed the torture of Abu Zubaydah by the military and the CIA, expressed alarm to their headquarters; by fall 2002 (a year before the worst abuses in Abu Ghraib, and a year and a half before those abuses were made public) FBI agents’ continuing distress regarding military interrogation practices at Guantánamo had reached the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice and the Attorney General of the United States, John Ashcroft.46 The conflict between the FBI and the military became most intense over the interrogation of al-Qahtani and Mohamedou Ould Slahi.47 In both cases, the aversive interrogation procedures were directly approved by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld. The FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, through fingerprints and timing, had discovered al-Qahtani’s role in the events of 9/11, but at Guantánamo the military was subjecting al-Qahtani to forms of questioning that were not only absolutely prohibited by the FBI on moral and legal grounds (it allows only “rapport based” techniques), but would surely ruin any chance of getting actual information.48

Although a formal system of reporting within the FBI only began after the Abu Ghraib revelations, an elaborate survey of one thousand FBI agents carried out by the Office of the Inspector General at the Department of Justice in 2005 has documented the agents’ early and ongoing alarm, as well as their largely ineffective attempts to address it. The roughly 400-page A Review of the FBI’s Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantánamo Bay, Afghanistan, and Iraq is important for its record of cruelties, both inside and outside the interrogation room.49

What the study chronicles, however, is not only cruelty but also a kind of widespread cognitive anarchy across the three geographies of Guantánamo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. FBI agents were completely clear about what kind of deeds had to be reported if carried out by an FBI agent: criminal acts, misconduct, or any act that might be perceived by someone else, and later reported, as misconduct. They also understood their “obligation to report” the actions of non-FBI government employees if the act was criminal (an obligation all government employees have under federal law).50 Following the Abu Ghraib revelations, they were instructed that if they saw a person exceeding not the FBI interrogation rules, as in the past, but the rules governing the body to which that person belonged—whether military or the CIA—they were obliged to report that as well.51

But what were the rules governing those other bodies? The FBI agents did not know, and constantly emailed headquarters to ask what constituted “abuse.”52 The soldiers posted at U.S. foreign detention centers—perhaps because the Secretary of Defense had issued six different sets of rules—also did not know, though they cheerfully thought they did and repeatedly assured FBI agents that the events underway were legal: an FBI agent walking through a corridor at Abu Ghraib and seeing men in cells wearing only underwear (a violation of Geneva rules) was assured by a sergeant escorting him that their nudity was authorized; forty-seven separate FBI agents either saw or were told about sleep deprivation yet were informed that this was standard, approved military procedure; FBI agents present at Abu Zubaydah’s initial CIA interrogations were entrusted with the information that the procedures being used had been approved “at the highest levels.”53

The cognitive anarchy documented in the FBI Review again underscores the important phenomenon of transmissible authority. We saw earlier that a president’s lying about another country is far more criminal in its consequence than the lying of an ordinary citizen because it is a lie that will be transmitted across millions of people and because it authorizes the widespread infliction of injury and death. So, too, the White House’s decision to lift the prohibition on torture was transmitted to tens of thousands of soldiers who repeated false sentences about the suspendability of the Geneva Conventions and believed themselves authorized to practice once-forbidden acts. Even the one thousand FBI agents who would in the past have had the means to stop torture, lost their bearings and did not know what to report.54

President Bush’s assault on the rule of law has thus been devastatingly effective. But it is challengeable, and those challenges may come from a range of Americans and domestic offices. It is also challengeable in international arenas. An array of international legal challenges have already been issued against members of the executive branch who carried out President Bush’s program of “extraordinary rendition,” a process in which individuals were seized and flown to countries (often those with a history of practicing torture) to be detained and interrogated. In January 2007 German prosecutors in Munich issued arrest warrants for thirteen CIA agents who allegedly participated in the kidnapping and imprisonment of German citizen Khaled al-Masri.55 The following month, an Italian judge ordered the arrest and trial of twenty-five CIA agents who allegedly kidnapped Osama Mustafa Hassan Nasr on a Milan street and flew him to Egypt to be interrogated.56 Several studies carried out by the European Parliament—one completed in November 2006 and another in February 2007—have documented the 1,245 CIA flights that traveled through European airspace or made stopovers at European airports in the period between October 2001 and November 2006. In February 2007 the parliament voted to condemn extraordinary rendition and urged the twenty-seven member states of the European Union to continue their investigations and documentation of all flights.57

According to Sands, who has participated in international cases against government officials who torture, a case against President Bush or other members of his administration may be brought in an international forum. Citing Spain’s demand that England extradite former Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet for crimes he had committed twenty-two years earlier, Sands suggests how probable such a scenario is if the United States itself fails to confront the grave crimes carried out by the administration, and if Bush or Cheney travel to, or through, other countries in the near or even distant future.58

The Bush administration has dedicated itself to creating an alternative universe, an offshore world with no legal constraints on the American executive. Creating this universe has required fabricating stories and details, like the made-up account of nuclear weapons and the made-up account of Iraq’s connection to al Qaeda, and the made-up sources and dossiers for this made-up information. Ever effective at generating false information, torture has also been used to produce these fictions. Sometimes the interrogators wore fake uniforms and flew a false national flag. The administration has also falsified body counts and accounts of injury and suppressed genuine accounts.59 This fabricated universe also requires fabricating rules about habeas corpus to ensure that this made-up universe lies beyond the reach of real-world courts.

What has not been fabricated, however, are the actual injuries and deaths. The New England Journal of Medicine counts the number of dead Iraqi civilians at 151,000; in October of 2006 Great Britain’s medical journal Lancet placed the number at more than 650,000. The number, though uncertain, is real and large. The number of U.S. soldiers who have fallen as of August 18, 2008 is 4,145. The number of U.S. soldiers sent home with grave injuries is 13,453; another 17,056 less severely injured have remained on foreign soil.60 The number of people tortured is not at present known, but, again, the number is real. It may seem surprising that a fabricated universe can bring about devastating injury, but, of course, it is exactly the purpose of the real world system of laws to prohibit such injuries, so it is not surprising that fabricated worlds lead to widespread bodily harm.

The avenues of address that have been outlined above may seem inadequate to the harm done. Will the Congressional articles of impeachment remain stuck in the Judiciary Committee? Will the Justice Department appoint a special counsel to investigate the White House authorization of torture? Will any state’s Attorney General now answer Bugliosi’s call to prosecute President Bush for the deaths of U.S. soldiers? Will other towns join Brattleboro and Marlboro by drafting and publishing their own indictments and arrest warrants, thus transforming the Brattleboro-Marlboro symbols into profound safeguards against future executive wrongdoing? Will the Second Circuit Court of Appeals hear Arar v. Ashcroft without this time allowing national security claims to silence the case? Will the United States extradite the thirteen who have been indicted in Germany for their part in the rendition of a German citizen? Will Belgium reinstate the “universal jurisdiction” statute that they repealed when former Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld threatened to have NATO headquarters moved because a Belgium court had agreed to hear a war crimes case brought by a group of injured and bereaved Iraqi civilians?

“How long won’t you stand for injustice?” asks Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage. If you’re going to get tired after half an hour, she advises, or after a week, or after a month, you might as well leave right now. Mother Courage storms into a military headquarters to lodge a complaint, and, finding a young lieutenant there who is waiting to make his own complaint, she launches into her disquisition on the impossible fortitude and stamina required, and does this so effectively that she persuades herself. She promptly leaves without lodging any complaint. The event takes place shortly after the military execution, without trial, of her soldier son.

Part of what makes the thought of prosecuting Bush so aversive is that it would be utterly exhausting. President Bush has repeatedly short circuited protest against one outrageous illegality by quickly carrying out a second, third, fourth, and fifth, so that the citizenry is kept in a permanent state of astonishment and cannot recover its own ground long enough to do more than cry out. Now, at the end of his administration, the sheer number of accumulated wrongful acts disempowers the collective will to act, and tempts us to elect our way back into a legal order, and simply close the door on the revolting spectacle of the last eight years.

But is closing the door actually an option? If the country is to renew its commitment to the rule of law, that outcome will require reeducating ourselves about what the law is. The law aspires to symmetry across cases. Among the more than two million Americans in prison and jail in 2006 was a young woman, Lynndie England, whose smiling face was photographed at Abu Ghraib as she held a dog leash attached to the neck of a naked prisoner. Yet at Guantánamo, where direct White House agency has been elaborately documented, the long list of acts actually practiced includes: “Tying a dog leash to detainee’s chain, walking him around the room and leading him through a series of dog tricks.”61 How long won’t you stand for injustice?

The legal memos to and from the White House have no power to alter the national and international rules against torture. Geneva rules state that they cannot be suspended in wartime, and a country can only withdraw from the accords in peacetime with a one year lead time. Though the definition of torture in the Convention Against Torture is 118 words long, it has only “two key elements” that must be present: “that the act intentionally cause severe suffering and that it have official sanction.”62 The legal memos back and forth among the White House, the Secretary of Defense, and the Office of Legal Counsel, far from minimizing the crime of torture, fulfill its definitional requirements by verifying that it was done with “official sanction.”

Finally—and for us, most important—the international rules against war crimes and torture do not allow prosecution to be thought of as discretionary; they do not allow an escape provision based on electoral euphoria or on one’s doubts about one’s own stamina in fighting injustice. Very distant from a mere disinclination to prosecute is a country’s act of granting an amnesty. The international laws about some criminal acts do, in fact, allow for amnesty if required to establish peace. But torture is not one of those crimes. As Michael Scharf writes, the Commentary to the Geneva Conventions (the “official history” of their adoption) “confirms that the obligation to prosecute is ‘absolute,’ meaning . . . that states parties can under no circumstances grant perpetrators immunity or amnesty from prosecution for grave breaches.”63 So, too, the Convention against Torture requires that states “submit” cases to the “competent authorities for the purpose of prosecution.”64 This means, writes Scharf, that “where persons under color of law commit acts of torture in a country that is a party to the Torture Convention, the Convention requires Prosecution.”65

The United States is a party to these agreements. The duty to prosecute means that the failure of a government to do so violates international law and that the country reneges on its treaty obligations.66 It also increases the pressure of other countries to bring cases against President Bush, Vice President Cheney, and former Secretary of State Rumsfeld based on the principle of “universal jurisdiction” that permits all parties to a treaty to prosecute grave war crimes that originated in another country.

It is odd that the designers of the Brattleboro resolution used “universal jurisdiction” as one of its legal bases, since that doctrine exists to enable countries distinct from the wrongdoer’s home ground to indict and arrest them. It is also odd that New York City’s Center for Constitutional Rights, which in 2004 successfully argued for Guantánamo detainees to be heard in federal court, a year later chose to file a torture case by Iraqi prisoners against Donald Rumsfeld in Germany rather than in the United States. Their choice of venue was based on the fact that Germany has an explicit statute permitting them to try war crimes carried out anywhere in the world if the home country neglects to do so. The logic both in Vermont and New York seems to be: if the doctrine of universal jurisdiction allows citizens of a different country to try a case, surely it authorizes citizens of the home country to do so. Perhaps the valiant Brattleboro citizens and the stern fighters at the Center for Constitutional Rights doubt whether the ground they stand on is still in the United States. Can the ground be put back under their feet? How long?

Notes:

1) The town resolutions against the Patriot Act can be read on the Web site of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee: www.bordc.org.

2) The town resolutions urging impeachment can be read at www.afterdowningstreet.org.

3) Vincent Bugliosi, The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder (Vanguard Press, 2008). Bugliosi is not unmindful of the horror of the Iraqi dead; the U.S. laws under which the case he outlines would be tried do not, however, accommodate foreign soldiers and civilians.

4) Senate Report on Whether Public Statements Regarding Iraq by U.S. Government Officials Were Substantiated by Intelligence Information, p. 71.

5) Senate Report, p. 80.

6) Senate Report, pp. 55, 56.

7) Senate Report, p. 72.

8) Jane Mayer, The Dark Side (Doubleday, 2008), p. 137.

9) Senate Report, p. 81.

10) Senate Report, p. 82.

11) Senate Report, pp. 14, 15 quoting Dick Cheney, speech made in Casper Wyoming and distributed by Associated Press, September 20, 2002; and Meet the Press, March 16, 2003. Emphasis added. In an interview, Cheney retracted his statement that Saddam Hussein “has, in fact, reconstituted nuclear weapons,” but many more people saw Meet the Press than saw the interview.

12) Senate Report, p. 7 notes 11 and 13, citing CIA and Department of Energy reports.

13) Senate Report, pp. 4, 5, 14.

14) In general, Colin Powell is much more careful to cite ambiguities and equivocations than are George Bush, Dick Cheney, or Condoleezza Rice. However, Powell will sometimes build from that position of acknowledged uncertainty to a climactic certainty that (precisely because of his willingness to be detailed and nuanced) ends up being dangerously compelling. In his UN speech in February 2003, he alludes to the uncertainty surrounding the aluminum tubes, then goes on to make their use in nuclear weapons sound certain (Senate Report, p. 5). Again, with regard to the 5-7 year time window: in his September 26, 2002 testimony before the Senate he includes a sentence that acknowledges the possibility that the completion of a weapon of mass destruction may be 7 years away, but also includes what is nowhere present in the intelligence, that it may be 1 day away: “They have not lost the intent to develop these weapons of mass destruction, whether they are one day, five days, one year or seven years away from any particular weapon” (Senate Report, p. 45).

15) Senate Report, p. 4.

16) Senate Report, p. 5.

17) Senate Report, “Minority Views of Vice Chairman Bond and Senators Chambliss, Hatch, and Burr” pp. 102, 103.

18) This is not say that the speakers repeating the president’s words—a list that includes former presidential candidates Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, and John Kerry as well as John Rockefeller, the chair of the committee authoring the Senate Report—are wholly without fault. Some senators, hundreds of thousands of citizens, and many citizens of many other countries went on record as saying no evidence warranting invasion had yet been given.

19) Thus Vincent Bugliosi reminds us that in September 2001 a national poll showed that only 3 percent of the population mentioned Iraq as a possible participant in the events of 9/11; by August 2002, 70 percent of the population attributed responsibility to Iraq. So often was the lie repeated by the White House that even after President Bush eventually acknowledged that there was no evidence linking Iraq to 9/11, 43 percent of the population continued to believe Iraq was responsible; among troops in Iraq, the figure is 90 percent (Prosecution of George W. Bush, pp. 137, 138).

20) For example, a report issued by the Inspector General at the Department of Defense (February 2007) states that the Pentagon “inappropriately disseminated” an analysis linking Iraq and the al Qaeda 9/11 terrorists that intelligence had been “unable to substantiate.” The 2004 Senate Report examining the accuracy of the pre-war intelligence noted, “the DoD policy office attempted to shape the CIA’s terrorism analysis in late 2002 and, when it failed, prepared an alternative intelligence analysis denigrating the CIA for not embracing a link between Iraq and the 9/11 terrorist attacks (2008 Senate Report, pp. 89, 90, 92, citing 2004 Senate Report). As later sections of this essay will indicate, the pressure to produce information about an al Qaeda–Iraq partnership appears to have involved the White House licensing of torture. This possibility is not included in the Senate Report, except in its account of al-Libi as described above.

21) Senate Report, p. 92.

22) Bugliosi pursues both these matters in Prosecution of George W. Bush.

23) Jeremy Waldron, “Torture and Positive Law: Jurisprudence for the White House,” 105 Columbia Law Review 6 (October 2005), pp. 1749, 1727, 1735.

24) Philippe Sands, Torture Team: Rumsfeld’s Memo and the Betrayal of American Values (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), pp. 63, 64.

25) Final Report of the Independent Panel to Review DoD Detention Operations [The Schlesinger Report], in ed. Mark Danner, Torture and Truth (New York: 2004 ), p. 365. In her interview with Major General Taguba, Karpinski had cited the repeated visits of Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz to Abu Ghraib, without indicating whether he was the official who conveyed the White House’s keen interest in the interrogation results (Interview Transcript included in “The Taguba Report: Article 15-6 Investigation of the 800th Military Police Brigade” in Karen J. Greenberg and Joshua L. Dratel, The Torture Papers: the Road to Abu Ghraib, [Cambridge University Press, 2005]).

26) Cited by Jordon J. Paust, “Above the Law: Unlawful, Executive Authorizations Regarding Detainee Treatment, Secret Renditions, Domestic Spying, and Claims to Unchecked Executive Power,” Utah Law Review (2007), no. 2, p. 348.

27) Mark Mazzetti, “Ex-Pentagon Lawyers Face Inquiry on Interrogation Role,” New York Times, June 17, 2008.

28) Joby Warrick, “Justice Dept. Urged to Examine Authorization of Harsh Interrogation Tactics,” Washington Post, June 7, 2008.

29) Scott Shane, “Elusive Starting Point on Harsh Interrogations,” New York Times, June 11, 2008.

30) Major General Antonio Taguba, preface to “Broken Laws, Broken Lives,” http://brokenlives.info/.

31) Justice Stevens, quoting INS v. St. Cyr, 533 U.S. 289, 301 (2001) in Shafiq Rasul, et al., Petitioners v. George W. Bush, President of the United States et al., June 28, 2004, p. 5.

32) Justice Stevens, quoting Braden v. 30th Judicial Circuit Court of Ky., 421 U.S. 484, 495 (1973) in Rasul v. Bush, p. 10.

33) Justice Stevens, Rasul v. Bush, p. 17.

34) Justice Stevens, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, Petitioner v. Donald H. Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, et al. June 29, 2006, p. 53.

35) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, p. 61.

36) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, pp. 50, 51.

37) Oral Arguments, Rasul v. Bush, April 20, 2004, pp. 3, 8, 15.

38) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, pp. 25, 69 (four times), 70 (twice); Kennedy, Hamdan vs. Rumsfeld, pp. 2 (twice), 6, 8 (four times), 9, 10 (twice), 16, 19, 20.

39) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, p. 72. Emphasis in original.

40) Kennedy, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, p. 7.

41) Stevens, Hamdan p. 69; Kennedy, Hamdan p. 8.

42) One might argue that all three legal grounds—the Geneva Conventions, the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and the absent Congressional legislation—provide equal foundations for Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. But as Justice Kennedy notes in his concurring opinion, the requirement to follow the court martial procedures of the UCMJ or to have Congress provide a legislative base are both themselves derived from the Geneva requirement for a “regularly constituted court“ (Kennedy, p. 2).

43) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, pp. 58, 61 (drawing on W. Winthrop, Military Law and Precedents [re. 2d ed. 1920], p. 831).

44) Stevens, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, p. 72.

45) Kennedy, Hamdan p. 2; Stevens, Hamdan p. 27.

46) Office of the Inspector General, U.S. Department of Justice, A Review of the FBI’s Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantánamo Bay, Afghanistan, and Iraq (2008), pp. ix, xi, xxii.

47) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, pp. 122, 123.

48) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, p. 78. From 2002 onward an important voice in maintaining the FBI’s adherence to its exclusive reliance on rapport-building techniques was Assistant Director Pasquale D’Amuro, who stressed in high-level meetings that force techniques, even though apparently approved by the White House Office of Legal Counsel, would produce false information, would make any testimony received from the detainee inadmissible in court, and would in the long run be the subject—he predicted—of a Congressional hearing (Review of the FBI’s Involvement, pp. 71, 72).

49) The Review of the FBI’s Involvement acknowledges that the FBI reports understate what took place: the FBI officers had access only to military interrogation centers, not to the CIA black holes; of those military centers, FBI agents at Abu Ghraib never saw the inside of the building where the events that later became notorious took place; and they were never on the ground at night when most abusive acts occurred. FBI rules required that the agent leave the room if any act incompatible with the FBI’s own procedures began. Therefore they were able to report only what they witnessed at the opening of the session. Only the classified version of the Review of the FBI’s Involvement contains the full description of what FBI agents witnessed in the interrogations of “high value” detainees such as Abu Zubaydah (see p. x, note 5; and blacked-out passages throughout the report).

50) 28 U.S.C. sec 535.

51) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, p. 52.

52) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, passim. One agent in Afghanistan contacted headquarters to ask how much time had to elapse between the abusive non-FBI interrogation and his own in order for the information he received not to be contaminated by that other interrogation (xv). The Justice Department Report concludes that the FBI still has not answered this critically important question (xvii).

53) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, pp. 252, 255, 69.

54) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, p. 1.

55) Hugh Williamson, “Germany Seeks Arrest of 13 ‘CIA Agents,’” Financial Times, January 31, 2007.

56) Tony Barber, “Americans to Stand Trial in Rendition Case,” Financial Times, February 16, 2007. The former head of the Italian intelligence service was also charged by Judge Caterina Interlandi for the assistance he allegedly gave to the American agents.

57) Tom Burgis, “Poland, Italy ‘Colluded on CIA Detentions,’” Financial Times, November 28, 2006; and Andrew Bounds, “MEPs Condemn Rendition Flights,” Financial Times, February 14, 2007.

58) Sands, Torture Team, p. 204. Britain’s handling of Spain’s request for Pinochet’s extradition is described at length in Sands’s earlier book, Lawless World (Penguin, 2005), pp. 23-45.

59) See Articles of Impeachment, article 10. See also E. Scarry, “Rules of Engagement: Why Military Honor Matters,” Boston Review, November/December 2006, pp. 23-30 (https://www.bostonreview.net/BR31.6/scarry.php).

60) Department of Defense, “Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) U.S. Casualty Status Fatalities as of: August 18, 2008, 10 a.m. EDT (http://www.defenselink.mil/news/casualty.pdf, accessed August 18, 2008).

61) Review of the FBI’s Involvement, p.102. See also Philippe Sands, “Interrogation Log of Detainee 063, Day 28, December 20, 2002,” Torture Team, p.106. Sands ends each chapter by including a passage from the interrogation log of detainee al-Qahtani, a deeply effective way of alerting the reader to the concrete discrepancy between one’s freedom to read and what happened to this prisoner in fifty-four days of consecutive torture. One inevitably feels, after one turns the page to start a new chapter, and enters into the fascinating details of life in Washington D.C., that one has left the torture itself behind, only to be reminded at this new chapter’s end, that the torture continues. Though the time it takes to read the book is half a day, al-Qahtani was tortured for fifty-four days. Interrupting the reading act with the record of his torture acquaints the reader with the sense of unending time.

62) Roman Boed, “The Effect of a Domestic Amnesty on the Ability of Foreign States to Prosecute Alleged Perpetrators of Serious Human Rights Violations,” 33 Cornell International Law Journal, 297 (2000), p. 311.

63) Grave breaches include “willful killing, torture, or inhuman treatment, including . . . willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, extensive destruction of property not justified by military necessity, willfully depriving a civilian of the rights of a fair and regular trial, and unlawful confinement of a civilian.” Michael Scharf, “Accountability for International Crime and Serious Violations of Fundamental Human Rights: the Letter of the Law: the Scope of the International Legal Obligation to Prosecute Human Rights Crimes,” 59 Law & Contemporary Problems 41 (1997), pp. 43, 44.

64) Conventions Against Torture, quoted in Scharf, p. 46. Because the wording requires “submitting the case” to prosecution rather than requiring “prosecution,” some analysts have seen the Convention as less than absolute; but Scharf compellingly argues that the “submit for prosecution” language is there to allow for the possibility that the person’s innocence or the lack of evidence then leads to a release from prosecution. On this point, see Scharf, p. 46 and Boed, p. 321.

65) Scharf, p. 60.

66) Boed, p. 322.