Someone, I think Boris Vian, described the 'Pataphysician as that individual who, given a form to fill out in triplicate, throws away the carbons and completes each form individually-with different information on each. Even this response would prove too straightforward for Oulipians. They'd kick the game up a few notches, creating elaborate anagrams for the first sheet, perhaps, allowing themselves use of a single vowel for the second, for the third replacing each noun with its next door neighbor from the dictionary. Or as Raymond Queneau, co-founder with François Le Lionnais of Oulipo (for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, workshop for potential literature), described them: "Rats who build the labyrinth from which they plan to escape."

For all its seriousness, the French avant-garde has retained a sense of fun missing from its counterparts in the English-speaking world. It's impossible to imagine a writer like Queneau, for instance, eventuating anywhere but in France. His first novel began as a playful translation of Descartes into spoken French; in another, a character escapes its book and, like Gogol's nose, roves all about Paris having adventures, pursued by its desperate author; his Exercises in Style relates the same incident in ninety-nine versions ranging from anecdote to reportage to haiku to philosophical treatise.

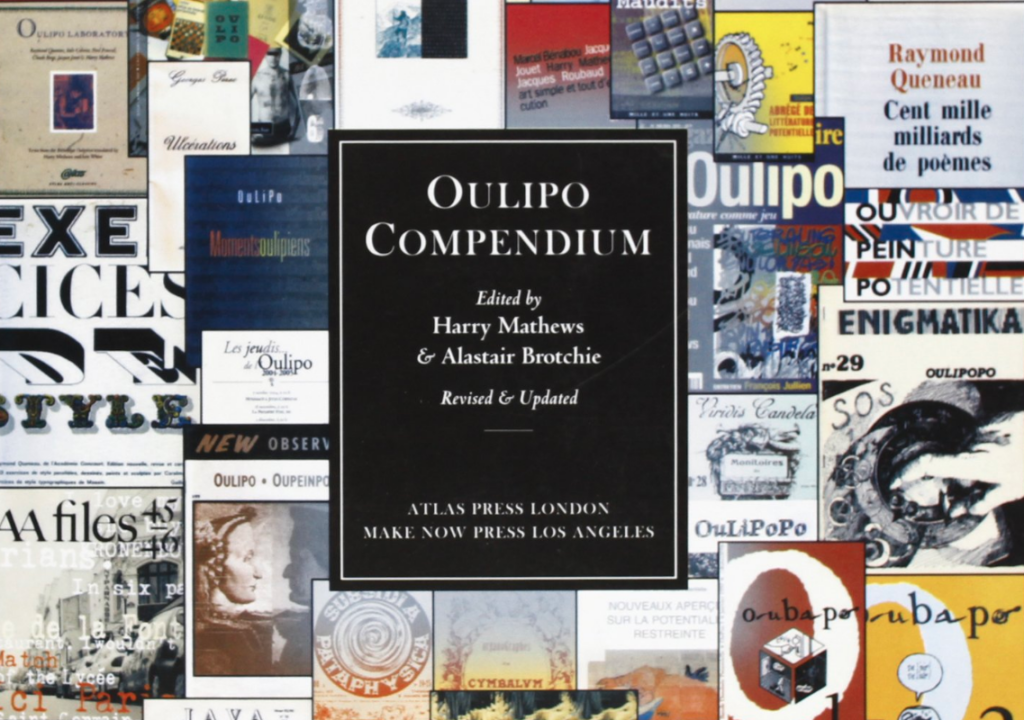

Though largely unknown in the United States, Queneau is a direct precursor to much that is most interesting and influential in modern continental literature, from surrealism and le nouveau roman to contemporary experimentalism and the postmodern. Atlas Publishers have made it their brief over the past few years to present the documents of the avant-garde, and they now offer this beautifully produced notebook-part sampler, part reference work, part travel guide-of the equally neglected Oulipo. Subtitled "Atlas Archive Six," the compendium joins earlier Atlas volumes such as The Dada Almanac, The Book of Masks (on French Symbolist and fin-de-siecle decadent writing), A Mammal's Notebook: Collected Writings of Eric Satie, and The Automatic Message, an anthology of generative Surrealist works by André Breton, Paul Eluard and Philippe Soupault.

If 'Pataphysics was, as claimed, the science of imaginary solutions, then Oulipo might be described as that of imaginary problems, a small monument to man's stubborn insistence upon making things as difficult as possible for himself. Appropriately, the Compendium begins with Queneau's "Cent mille milliards de poèmes," written in 1960, the same year he founded Oulipo. This work consists of ten 14-line sonnets written in such a way that, as with books of heads, bodies and legs for children, any line may be juxtaposed with any other. (Dotted lines are provided to cut along.) Queneau, ever the amateur mathematician, put tongue firmly in cheek and calculated that the reader would require 190,258,751 years to read the book in its entirety. If this seems thoroughly mad as a project for the writer, consider the translator's plight. Yet Stanley Chapman, whose translations include spectacularly felicitous editions of Boris Vian's novels, has done an outstanding job. Here, assembled quite at random, is a sonnet:

Don Pedro from his shirt has washed the fleas

His nasal ecstasy beats best Cologne

The Turks said just take anything you please

And empty cages show life's bird has flown

It's one of many horrid happenings

Nought can the mouse's timid nibbling stave

Proud death quiet il-le-gi-ti-mate-ly stings

For burning bushes never fish forgave

Staunch pilgrims longest journeys can't de press

In Indian summers Englishmen drink grog

On wheels the tourist follows his hostess

We'll suffocate before the epilogue

Ventriloquists be blowed you strike me dumb

he bell tolls fee-less fi-less fo-less fum

How you feel about that is likely to prove a good indicator of your attitude towards Oulipo. Think it's silly? Then Oulipo may not be for you. But if instead you find it intriguing, if you sense the energy roiling up out of those odd joinings, if it makes you laugh or cock your head to one side for a moment to think, if you sense, yes, the potential, then this book may become for a time your new best friend.

An essentially collaborative effort to create new work by arbitrary systems of constraint, recombination, transposition, and displacement, Oulipo is on one level a game-though of course all art is game-playing. And on another level, it is a means of breaking through what one knows and knows how to do, a way of forcing oneself to think in different categories, to come face to face with the surprising. Take the lipogram, for instance: a text excluding one or more letters of the alphabet. Georges Perec wrote an entire novel, A Void (La disparition), without using the letter e. Walter Abish's Alphabetical Africa consists of 52 chapters, each word in the first chapter beginning with a, each in the second chapter with either a or b and so on, until with chapter 26, where all letters are allowed, the process reverses, each word in the final chapter again beginning witha. Others have written texts in which each noun was replaced by that found seventh ahead of it in the dictionary, texts using no letters that extend above or below the line, texts in which all r's have been eased-make that erased.

Though in no sense is this a mere glossary, editors Mathews and Brotchie arrange their material alphabetically. "Processes, definitions, and personalities," they say, brief entries of biography and unusual reference (a definition and examples of homosemantic translation, for instance) opening onto longer discussions of various schemata for composition, both in theory and as realized in specific works. Included are discussions of such Oulipo keystones as Queneau's Exercises in Style and Georges Perec's Life A User's Manual, as well as generous samples of work from the panoply of Oulipian activity. Shorter sections on Oulipopo (crime fiction), Oupeinpo (painting) and Ou-x-pos (comics) supplement the 250-page Oulipo section.

Of particular interest, offered here as introduction, is Jacques Roubaud's "The Oulipo and Combinatorial Art," a readable and often hilarious summa of things Oulipian. In describing the group's founding, for instance, referring to the many schisms, dismissals, and leavetakings of the Surrealist movement:

b. No one can be expelled from the Oulipo.

c. Conversely (you can't have something for

nothing) no

one can resign from the Oulipo or stop be-

longing

to it. . . . The dead continue to belong to the

Oulipo.

Or, speaking of its methodology:

For anyone at all familiar with literature

of Oulipian inspiration, it is obvious that many

of the constraints it uses predate the foundation

of the Oulipo: they are to be found scattered

across the world and the ages. We have described

this phenomenon as anticipatory plagiary.

Or here, addressing rather brilliantly, I think, the group's origins in what one might think of as the eternal avant-garde:

The reasoning is as follows: "asserting one's

freedom" in art makes sense only referentially-

it is an act of destroying traditional

artistic methods. After these crises of freedom-

they are often creative and enriching

in their opposition to the fossilised relics

of tradition-it finds sustenance only in a

parrot-like repetition of the original gesture,

a self-parody that immediately becomes irrelevant.

One then finds oneself confronted

with an increasingly weak, sad, and bitter

involvement with the unconscious leavings

of tradition.

Harry Mathews, Alastair Brotchie, and Atlas Publishers are to be congratulated and resoundingly thanked for bringing this volume together, making available for the first time in English a clear view out of the Oulipian window, where strange smiling folk carry their imaginations like small silver buckets about the world.