“First causes,” wrote Charles Olson, “were Melville’s peculiar preoccupation.” A fixation on origins and impulses, though, is hardly peculiar to Melville: Olson was equally obsessed with primary, primal forces, among which Herman Melville claimed a privileged spot. Both writers, in turn, are marks on the “mappemunde” that Susan Howe has drawn for over three decades. A poet-scholar of usufruct and formidable innovation, Howe has engaged Melville as a source text precisely by considering the sources of his texts. Olson himself has never been a subject of Howe’s inventive investigations, but his ambition and methods certainly inform hers. Similarly rooted in New England—a generation and a gender apart—the poet who traced the founding of Gloucester, Massachusetts in his Maximus Poems and the poet who moves from “from into the way that leads to” in Souls of the Labadie Tract are companion figures of forage, writing through reading and research, transcription and scraping together. Straddling the Aristotelian distinction between historian and poet, Howe, like Olson, leans imaginatively into possible futures while looking behind, interpreting what happened.

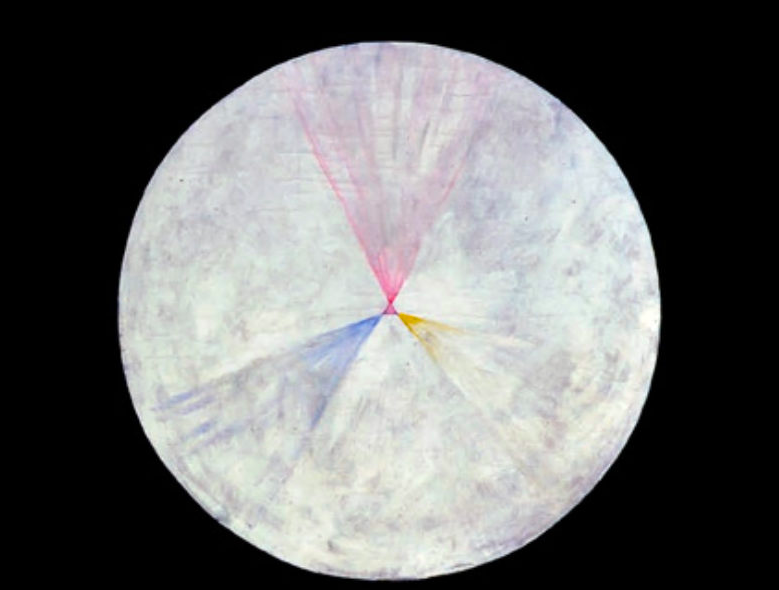

Souls, Howe’s first full-length collection since The Midnight (2003), is an excavation of site and citation, of quasi-utopian polis and poetry “half-smothered in local history.” The notion of “tract” articulates its provenance: a piece of land and a written document. Juxtaposing territory and text, the title poem’s final page comprises a map of the Labadie Tract, a parcel of 3750 acres that in 1684 became home to the Labadists, a Utopian Quietist sect. Depicting the site where Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania converge, the map both represents a crossroads and is itself a crossroads where image intersects with language. Complicating the exchange is a conflation of foreground and back-. The map features a vignette of a single tree (the Labadie poplar) and various waterways resembling a bigger tree’s branches; what appear to be smaller rivers turn out to be trails. Such doubling resounds throughout the poem: truth/trust, blunder/blind, and so on. If Howe is exquisitely sensitive to the physical relations between words (and she is), she is no less so to the resonance between her material and its original context, and Souls charts her effort “to transplant words onto paper with soil”—that of region and of lineage—“sticking to their roots.”

Many writers have constituted the occasions, indeed the unprocessed matter (inventories, squibs, daybooks, drafts) for Howe’s unique treatment—a treatment not of their ideas, per se, but of their practice. Howe does not so much “write through”—as John Cage did—precursors like Thoreau, Peirce, Swift and Stella, as allow herself to be written through. In the Reverend Hope Atherton, for example, she has found “the authority of a prior life for my own writing voice.” This admission is found in a prose text called “Personal Narrative” which, like most of Howe’s books’ seemingly prefatory remarks, proves pivotal to what follows. While the text contains transparently autobiographical information, the “personal” is characteristically channeled from somewhere outside her. An indebted, even insolvent poet, unabashed at being “eternally belated,” Howe has always made inheritance an integral topic of her work; here it is the central concern. Resolutely hooked into a “sonic grid,” hospitable to the “solicitation of innumerable phantoms,” she is uninterested in killing off her fathers, as per Bloom’s agonistics, let alone her mothers. Instead, she affirms the “chemical almost mystical” conversation, traversing time and context, that gathers “our great great grandparents, beginning at the greatest distance from a common mouth” into its elastic fold.

A self-conscious soteriology pervades the notion that “all meet at last, clothed in robes of glory.” Indeed, the last intact word of the book’s last sequence, “Fragment of the Wedding Dress of Sarah Pierpont Edwards,” is divine: “I have already shown that / space is God.” Howe sustains the spirit of what is said—though never at the expense of the letter. For we “cannot afford to dishonor any typographical item,” she warns, “with stark vernacular,” and in fact it is the textual outcast that earns her scrutiny: the marginal or “misshapen,” blank space, the dyslexic inscription, para- and peripheral texts. (This is where Howe’s allegiances to both lyric and Language poetries reside, of course, since a word in her work acts as window and impenetrable pane alike.) The ancestral dialogue she overhears is not necessarily comforting or coherent, for some “sources,” she notes, are “running directly contrary to others.” Nor may “God” have the ultimate say: the book’s final page presents a vertical line of obscured lettering, in which the reader discerns—just maybe—a trace of “a trace of a,” perhaps “a trace of a stain of a.” The Word, once said to be “In the beginning,” is exhausted and wanes at the end—of the world, or at least of this poem. The typefaces of “Fragment,” some bolded, others italicized, many illegible or misaligned, are resolved only to the degree they disappear. A textus in the dual sense of textile and text, the volatile poem is a polygraphy that atrophies, or entropies, unraveling to barely a thread.

Less apocalyptic than merely posthumous, the assembly of souls that Howe envisions will be filed, as she puts it, by “call number coincidence.” The logic she petitions is not that of Revelations but of the library and the database. Her earlier forays into Pragmatism here assign a clear mode and mandate to the poet-historian, consistent with Derrida as well as Aristotle: to organize and augment knowledge, as “raw material paper afterlife,” in readiness for the “vampirism” of future library denizens like herself. The alpha of Howe’s work is the archive—“a damaged edition’s semi-decay is the soil in which I thrive”—and the archive is its omega. When she recalls securing a “green card” to Yale University’s Sterling Library, the term evokes movement, immigration, and residency. But special collections are also zones of “impervious classification,” she fears, insinuating entrapment or exclusion, the sense that, “We are strangers here / on pain of forfeiture.”

Souls acknowledges a prodigious anthology of “Verbal echoes so many ghost / poets I think of you as wild / and fugitive.” Though anonymous, among the guests hosted by, or haunting, the book’s title poem is T.S. Eliot. In The Midnight, Howe stated that Eliot’s “Little Gidding” has served her “as a beacon for what poetry must achieve,” and “Souls of the Labadie Tract” harkens to Eliot’s last major work, its forty-four stanzas intimating four quartets. But the relationship between “Souls of the Labadie Tract” and “Little Gidding” is not only one of form. The Labadists—Dutch followers of French separatist Jean de Labadie—believed in “inner illumination, diligence, and contemplative reflection”; initially renounced private property; and supported themselves through manual labor and trade. William Penn admired the status Labadists accorded to women. Their anchoritic circumstances, valuation of simplicity and intense piety, even the short life span of their cooperative, bear striking similarity to the Anglican community founded in 1626 by Nicholas Ferrar in Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire.

There is no reason to assume Howe affirms either sect as offering an exemplary faith, especially when she calls “for why not unbelief”—and when the Labadists, according to Lucy Forney Bittinger, held slaves and leveled other cruel hypocrisies—or that she explores these socio-spiritual experiments for motives beyond “history qua history.” On the other hand, Howe’s attention to the ideals propelling these movements, when “public under- / current” in our own country is “grave,” seems less nostalgic or academic than flush with “Millennial hopes” for authentic interiority and genuine community.

Eliot’s earlier work is also a fragment that Howe shores against ruin, her question “Who is that phantom in / the foreground after you” conjuring The Waste Land’s “Who is the third who walks always beside you,” itself a citation from Shackleton’s Antarctic travel writing, which echoes strongly Luke 24. To the extent he is never counted, Eliot himself would seem to play the role here of enigmatic accompanist. His position “in / the foreground after you,” though, when he stands in the temporal background, ‘before’ Howe, means he is the addressee of her question, not the “phantom”: so there is yet a “third who walks always beside.” When Howe writes, “Poetry you may do the / map of Hell softly one / voice,” across the page from, “I’ll borrow chapel voices,” she invokes both Little Gidding’s chapel and The Waste Land’s original title, “He Do the Police in Different Voices.” Howe is precisely impersonating, down to her poem’s signoff, “Goodnight goodnight,” already an “ideate echo” of the 1922 precursor’s “Goonight. Goonight.”

Utterances in Howe are often borrowed—or better, “ownerless,” instances of “slippage.” The epigraph to Souls’s title poem is from Wallace Stevens, to whom Howe owes the seeds of the poem, which she explains arose while she was looking into family histories of him and his wife, Elsie Kachel Moll. That Howe alighted on a project while pursuing something else—that one genealogical research unearthed another—is an instance of the “inexorable order only chance creates” that she has long valorized. A later poem addressing Stevens, in turn, opens with a quotation by Henry James, which fittingly mentions an alter ego, as well as walking: Stevens and Jonathan Edwards, subjects of Howe’s earlier “Errand” diptych, each composed pensées while in transit, committing perceptions to paper slips that might well have resembled the swatch of Edwards’s wife’s dress.

Edwards pinned his inscribed slips of paper to his coat, “fixing in his mind an association between the location of the paper and the particular insight,” and locale is crucial to Howe’s Stevens, as well. The title of the poem about Stevens, “118 Westerly Terrace,” was Stevens’s address in New Haven (minutes away from where Howe now resides). “Life is an affair of people not of places,” he laments, “But for me life is an affair of places and that is the trouble.” Stevens’s interest in Conrad Weiser, who may have emigrated with his own forerunners, substantiates this focus. The latter was “a local hero in my part of Pennsylvania,” and reading his biography, Stevens admits in a letter, “has been like having the past crawl out all over the place.” The simile is very un-Howe (although a trio of “as if” invades one section of her poem), but the stress on past and location is mutual. Howe’s Stevens, born in Reading, is less a troubadour of lyric limpidity, ephebe of linguistic force, or metaphysician manqué than gumshoe anthropologist. Howe quotes from his Opus Posthumous, to emphasize the spectral and celebrate the secondary. Apologist for particulars, Stevens is here the descendent of “first parents,” a witness to when “Two ages overlap you and / your predecessors.” Reporting on the old-world syntax that bequeaths to the American patois its strata, Stevens notes that Weiser “has not corrected his spelling. When he speaks of pork he spells it borck.” This “Pennsylvania German,” Stevens confesses—its divergence from Queen’s English akin to the cleft between “Labadie” and “lappadee” that Howe indexes—“kept me up night after night wild with interest.”

Wildness runs wild in Howe’s book, as “true gold” and golden rule. “I believed in an American aesthetic of uncertainty,” she told the 2006 MLA convention for which “Personal Narrative” was originally written, “that could represent beauty in syllables so scarce and rushed they would appear to expand.” Souls of the Labadie Tract realizes those convictions, even as her appeal to “beauty,” her definition of poetry as “love for the felt fact stated in sharpest, most agile and detailed lyric terms,” will delight or disappoint readers who might have alleged, whether in tone deafness or out of some vestigial defense of tribal purity, that her texts oppose sonority, “near-at-hand” experience, or the concerns of a mainstream Modernism considered infallible to one cabal, “quietist” to another. Her work refutes Olson’s diagnosis that “what we have suffered from is manuscript,” and refuses his tenet, “not the eye but the ear,” but her projects nonetheless lend themselves to performance. (To wit: a recent electro-acoustic recording of “Souls of the Labadie Tract,” her second collaboration with composer David Grubbs.) Fascinated by “lexical inscape,” while allured by “allophone tangle,” too, Howe forges the spoken to script. “Font-voices,” she ventures, “summon a reader into visible earshot.”