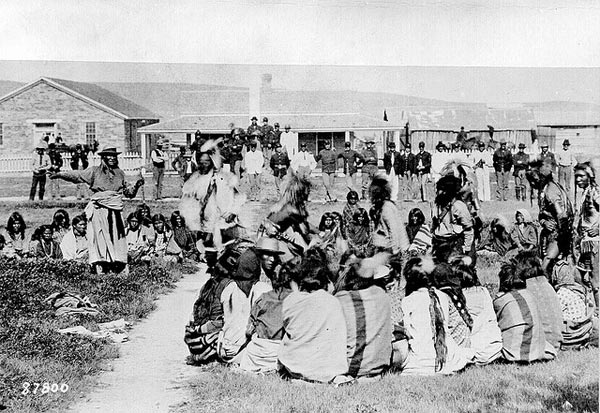

This past Friday, I wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post discussing the christening of U.S. military equipment with American Indian names. I argue that the choice of these names functions as a subtle form of propaganda because it suggests that the American Indians who were systematically killed, displaced, and forcibly assimilated by whites were powerful rivals of the United States and its armed forces. It is notable that white America—through its armaments, sports mascots, warrior narratives, and other means—emphasizes the skill and aggressiveness with which some American Indians resisted theft and genocide, rather than the facts of those crimes. Everyone knows these facts at least in general terms, and most of us genuinely feel badly about them, but our response is to pay tribute to the martial prowess of our defeated enemies. This choice of emphasis concerns me—specifically, the political ramifications of construing victims of imperialism as worthy opponents in a fair fight.

The article was widely misinterpreted as a brief for political correctness. I may not have made my case clearly enough, but no doubt the headline and publicity tweet the Post’s editors wrote without consulting me—a common hazard of publishing—contributed to the misunderstanding. The Post characterized the naming scheme as “offensive” and a “slur of Native Americans,” but these are not my words, they do not accurately convey my meaning, and I repudiate them without reservation. I would never describe the naming scheme as a slur because I have no idea if anyone is offended by the decision to call a missile Tomahawk or a helicopter Chinook. It is not for me to say, I did not say it, and it makes no difference to my argument.

I myself abhor political correctness. But the PC charge is not only misplaced here. It also burns with irony. The critics so quick and strident with their accusation are reinforcing the very phenomenon—political correctness—they claim to despise.

Political correctness is a project of decontextualizing language. When we are politically correct, we police our words to ensure we don’t say or write the ones that some critical mass of people finds offensive regardless of how they are used. So detested are these words that speaking them in any context is considered insulting.

A classic case is the word “nigger.” Thanks to overweening political correctness, you don’t hear it or see it in print even when you should: most mainstream journalists dare not use it even when reporting on its use by others. Instead the media censor it with bleeps and asterisks, resort to childish euphemisms such as “the n-word,” or contort their prose to avoid it. So deep is America’s hysteria that even saying something that sounds like nigger can get a person in trouble. (“Hysteria,” incidentally, is a valuable term too often disparaged as sexist even when it is clearly not being used to advance a sexist agenda.)

This is foolish because it assumes that certain words have unalterable meanings, persistent regardless of context. These words cannot be employed in service of a symbol or story because their symbol and story are constant and inherent in them. Indeed, some words, such as nigger and redskin, project meanings that are understood as pejorative (depending on who is saying them: context), but it is absurd to strike them from the language as a result, to refuse even to recognize their existence, and to reject them even for the purposes of educating and informing.

The politically correct demand—the radical disconnect of words from context—is precisely what my critics also demand. When one troll tweeted “Apache, Apache, Tomahawk, Redskin” at me, he did so, I assume, because he figured that they are not offensive words, but that I am oversensitive and would be insulted anyway. (In case it is not already clear: I am not insulted, on my own behalf or on anyone else’s.) That is to say, the sense of the word, from the troll’s perspective, is inherent in it. It is either actually offensive or it is not, no matter how it is used.

This is the essence of political correctness, and it is antithetical to my argument, which requires that we explore the context of use in order to grasp political narratives that unfold around and are predicated on language and symbols. More concretely, I am saying we should pay attention to context. My critics would rather ignore context and police language. They’d rather declare absolutely which words are offensive and which are not.

So, yes, someone in this debate is grasping for political correctness, but it is not me. My hope is to leave that sort of thinking as far behind as is possible and instead consider the reasons we tell the stories we do and the effects those stories have on our politics, whether or not those effects are intended.

In certain contexts, but not all, our naming tributes to American Indians can banish the discomfort, the sense of guilt that accompanies an uncompensated wrong, we ought to feel about the imperial nature of American conquest and the suffering it has caused. If we focused less on Indian bravery and combat skill and more on victimization, it would not be so easy to just acknowledge guilt and then shelve it in the backs of our minds. If we were not so comfortable, we would take up that guilt as a guiding star in the moral work of governance and accept that those who have been wronged are owed restitution and care, not just tribute and apology.

Sadly, however, reflexive political correctness is being marshaled in support of the political status quo and the historical readings that preserve it.