Democracy in the Time of Coronavirus

Danielle Allen

University of Chicago Press, $18 (paper)

Laboratories against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics

Jacob M. Grumbach

Princeton University Press, $29.95 (cloth)

In overturning Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court has given Americans yet another jarring reminder that these United States are deeply divided. Though Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health was not decided on federalism grounds, opponents of legal abortion have long argued that there is no national constitutional right to abortion and that state governments are the proper place for such decisions. The overnight implementation of abortion trigger bans in the wake of Dobbs has made good on that argument: the lives of women will now depend much more significantly on the states they live in, as the life and death of Black Americans did for most of U.S. history.

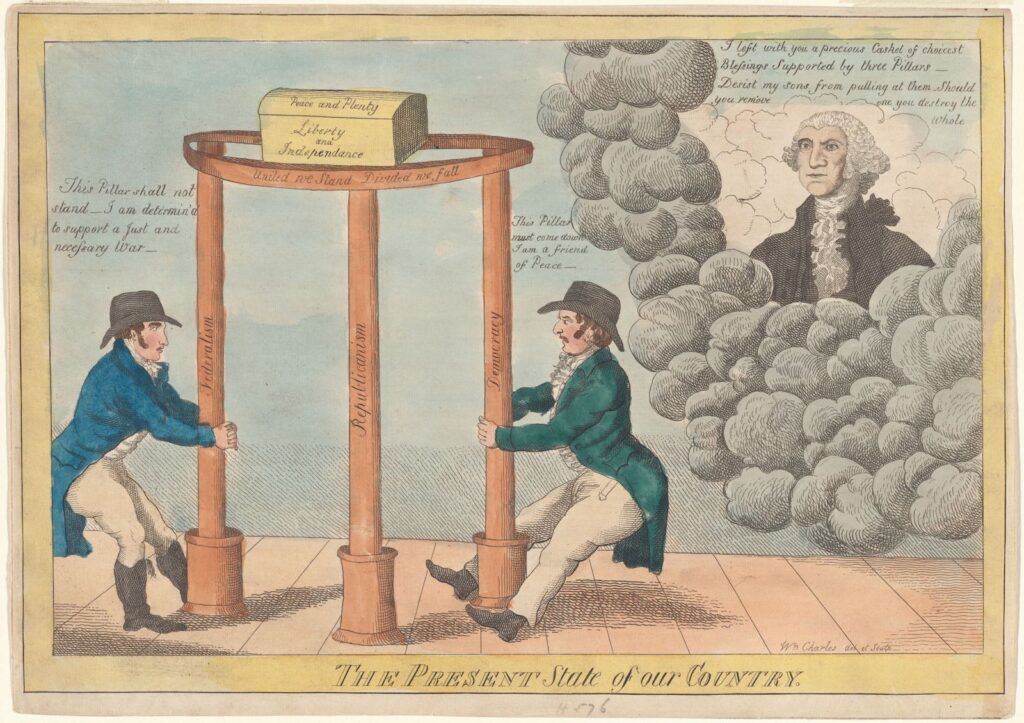

Critiques of federalism for suborning injustice are familiar on the left. Many hear “states’ rights” as a conservative dog whistle, tainted by association with the likes of John C. Calhoun, George Wallace, and a long line of other reactionary figures. In 1964, the same year that Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater ran a presidential campaign focused on states’ rights, political scientist William Riker famously wrote that “if in the United States one disapproves of racism, one should disapprove of federalism.” Though Riker later moderated that claim, generations of scholars echoed his conclusion, arguing that American federalism helped preserve slavery and serves as a major obstacle to social justice. The evidence also extends beyond the United States: scholars of comparative politics have found that some federal systems are associated with lower social welfare provision, higher inequality, and reduced political accountability compared to non-federal ones.

Yet this view has always had to contend with a hallowed tradition in American political culture that sees federalism as an unqualified good. Its virtues were neatly summed up by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a Ronald Reagan appointee, in a 1991 Supreme Court ruling about a Missouri state law requiring mandatory retirement for state judges at age 70. In the majority opinion, which found that the law did not violate the federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act or the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, O’Connor celebrated the power of the states as codified under the Tenth Amendment:

This federalist structure . . . preserves to the people numerous advantages. It assures a decentralized government that will be more sensitive to the diverse needs of a heterogeneous society; it increases opportunity for citizen involvement in democratic processes; it allows for more innovation and experimentation in government; and it makes government more responsive by putting the States in competition for a mobile citizenry. . . . Perhaps the principal benefit of the federalist system is a check on abuses of government power. “The ‘constitutionally mandated balance of power’ between the States and the Federal Government was adopted by the Framers to ensure the protection of ‘our fundamental liberties.’”

This lofty view has its own scholarly bulwark. Daniel J. Elazar argued that federalism could empower people’s need to unite for common purposes but also to remain separate to honor their unique and respective integrities, particularly in divided societies with deep sectarian conflict such as the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, or Northern Ireland. Political scientists, economists, and legal scholars in this tradition have argued that federalism can be a valuable constitutional arrangement that shares power but also preserves spheres of autonomy, helping to protect political minorities and avoid the dangers of too much centralization.

So, which is it? Does federalism promote democratic engagement, policy innovation, and protection from central government overreach, or does it facilitate elite power, exclusion, inequality, and limited accountability? Federalism interacts with a lot of other institutional details, so it doesn’t make sense to try to answer this question in a general sense. What we can ask is whether our federalism is good for us.

Federalism’s critics have typically come from the left and its proponents more from the right, but a curious thing happened on the way to the twenty-first century. Over the past twenty years, as gridlock hamstrung Congress and Republicans won the presidency twice despite losing the popular vote, progressive support for American federalism became more prominent. This shift predates the election of Donald Trump, but it gained significant traction afterward as cities and states resisted the backsliding of national norms on immigration and the environment. With national politics mired in stagnation and retrenchment, progress at state and local levels seemed more promising. These views only intensified after Trump and his acolytes tried to reverse the outcome of the 2020 election. The fact that so many officials at the state and local levels, including Republicans, upheld Biden’s victory was seen by some as a point in favor of federalism. In some progressive quarters of American politics, in short, there has been a rallying cry to double down on federalism’s apparent virtues.

Yet many remain skeptical, and two recent books reflect this divide. Danielle Allen’s Democracy in the Time of Coronavirus and Jacob Grumbach’s Laboratories against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics are both concerned with the role federalism plays in governance and democratic accountability. In terms of their research agendas and methods, these studies are not exactly in conversation with each other. Allen is a distinguished political theorist, and her book—published during her campaign for Massachusetts governor—has an aspirational quality; it is rich with discussion of the purposes of our federal constitutional democracy, the social contract, and political legitimacy. She focuses exclusively on COVID-19 but uses the crisis to illustrate the larger problems of U.S. governance. Grumbach, by contrast, is an empirical political scientist. He is less interested in contemplating missed opportunities for federalism than in assessing its actual impact on policy and social outcomes. He explores the impact of federalism on a wide range of policy issues in the era of high political polarization over the past several decades.

Reading the books together, despite their differences, helps to clarify what is at stake in debates about federalism in the United States. For Allen, the problem with U.S. pandemic response was our failure to capitalize on federalism’s virtues. Grumbach offers a sobering rebuttal, seeing these virtues as more illusory than real.

Before proceeding, some definitions are in order. Federalism is often conflated with decentralization, but the two are not the same. Not all decentralization is federalism, though all federal systems are decentralized to some degree. Most countries have different levels of government—vertical hierarchies that help administer or implement policy. What distinguishes a federal system from a unitary one is the constitutional relationship between the national and subnational governments.

In unitary states, like the United Kingdom and New Zealand, constitutional authority flows from the center. The national government can implement policy through regional governments or grant specific powers down the vertical hierarchy—as is true of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, for example—but the national government is invested with the ultimate legal sovereignty to determine the strength and scope of these decentralized powers. In federal systems, by contrast, both the central government and the regional units (like U.S. states) have constitutionally rooted, self-governing powers. While power can and does shift between levels, both the center and the periphery have at least some constitutional claim to sovereignty.

The historical emergence of such structures has followed two broad patterns. In some countries federalism originated from powerful centrifugal forces pulling the country apart. In those cases, it was crucial to guarantee sufficient authority to distinct regions, leading to what Alfred Stepan has called “holding-together” federalism (think Belgium or Spain). In other cases, federalism was a critical centralizing mechanism for constraining regional governments and ensuring enough central power to engage in nation-building: what Stepan calls “coming-together” federalism (think Switzerland or Australia).

Federalism in the United States was clearly of the coming-together variety. The Articles of Confederation of 1781 essentially maxed out state authority, requiring unanimous consent of the states in order to alter the limited powers it gave Congress. The new nation faced a series of major collective action problems: most states would be better off in the long run if they cooperated on economic and security issues, but in the short term any single state might be better off if it remained parochial and territorial. The only way to overcome this problem was to give the new central government enough authority to force greater cooperation; that is what spawned the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787. Delegates understood that the attachment to state power was an obstacle to the nation’s prosperity, not its salvation. As Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania put it, state authority was “the bane of this country.”

How is it, then, that so many Americans have come to think that the Constitution was designed to protect the states and to limit national authority, rather than the other way around? While the Federalists (more properly called Nationalists) won the ratification debates, the Anti-Federalists won the constitutional narrative. American federalism immediately became a “double battleground,” creating incentives for interested parties to move the political fight away from what government should do to arguments over which level of government should do it. Since the early republic, these arguments were more about power than principle. When national policies benefited regional elites, as when national banks helped the Northeast or the Fugitive Slave Act helped white enslavers in the South, state officials made passionate declarations of loyalty to the new national government. When national policies went against them, as tariffs did for many Southern states, they issued “ringing declarations” about state sovereignty.

At the core of American federalism, then, state sovereignty and limited (national) power have always been two sides of the same coin. Most federal democracies either provide the national government with sufficient powers to address a wide range of national problems or empower it to provide resources to the regional governments to do so. But in the United States, the power of the national government to address national problems is itself regularly contested, creating an extraordinarily decentralized system overlaid with periodic constitutional challenges to the authority of governmental at all levels.

American federalism has additional outlier features as well. All federal systems are decentralized, but the U.S. system exhibits decentralization on steroids: states are further divided into localities, adding more layers of elections and governance, and the national, state, and local governments are often doing the same kinds of things. In the United States there is no federal equalization of resources across the country that is found in other federal democracies. Bicameralism is a feature of all federal countries because they have a second legislative chamber to represent regional governments, but those chambers don’t always have equal legislative authority; the U.S. Senate does, however, and is one of the most malapportioned bodies in the world. The strong system of judicial review in the United States is also unusual, with federal courts routinely becoming involved in the most pressing and controversial political issues of the day. A significant part of the federal court docket is about the allocation of powers under federalism and the extent of congressional authority.

For defenders of federalism, this extensive diffusion of political power points to its democracy-enhancing possibilities. Many venues can serve as a mechanism for promoting citizen engagement, empowering political minorities and limiting the dangerous reach of central power.

In Allen’s analysis, the problem with the U.S. COVID-19 response was that it failed to capitalize on these potential benefits. Her book extends her work as director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, which led a major policy response initiative in the spring of 2020. Rather than see the pandemic as a utilitarian trade-off between economic prosperity and the protection of health, Allen argues that the crisis was existential and demanded a full mobilization of multi-level governance akin to fighting a war. That this did not occur at sufficient scale to prevent the deaths of over 1 million Americans (500,000 at the time of Allen’s writing) was largely the result of a crisis of legitimacy and the failure of the social contract. Federalism, in Allen’s view, can help to reinvigorate both.

Long before the pandemic, Allen argues, the United States was failing on many of the prerequisites of modern, well-ordered political regimes: basic material security, negative rights (like free speech and freedom of religion), positive rights (the right to participate and vote), social rights (like education and health care), as well as equality and non-discrimination. In particular, Allen highlights long-standing neglect of these basic needs for the elderly, essential workers, the young, and Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Indigenous, and rural Americans. In a chapter titled, “Federalism Is an Asset,” Allen argues that the United States should have more effectively capitalized on the strengths of federalism in response to the pandemic to build up these prerequisites. She situates her argument in the historical context of the Constitutional Convention and subsequent amendments to highlight the core values they produced: the national government should promote national purposes, equal protection of the laws, and harmony across the states, while regional governments should help integrate policy into the “networked structure of social life.”

Allen rightly notes that many of the problems that arose during the pandemic—collective action, supply chain, and fiscal solvency problems—were of central concern to the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. In her view, the federal structure that the Convention produced provides the tools necessary to respond to COVID-19 effectively. The national government should have activated its ample authority to temporarily control the supply chain of pandemic-fighting resources, served as a “backstop” for state and local fiscal health, and established a minimally acceptable floor on issues like mask mandates. State governments, meanwhile, operating within these national standards, could have designed the best ways to contract-trace, test, treat the sick, support the isolated, create in-person learning guidelines, and other policies in ways that best suited local needs.

Because Allen is particularly concerned with the fate of marginalized groups—the elderly, racial minorities, the poor—she also highlights the potential value of federalism as a resource for empowerment and equality. The tiered structure of American politics “modularizes our society,” she writes, so that those who are part of a minority can “nonetheless exercise majoritarian power within more local jurisdictions.” These groups can acquire autonomy and use power to shape policy in their distinctive interests, thereby more fulling empowering a diverse population. Here, Allen draws on the work of law professor Heather Gerken, who explores how federalism’s flexibility can provide additional routes to justice for these groups. Ideally, groups that were particularly hard-hit by the pandemic, especially Black and Latinx communities, would have been empowered to make more of the decisions that directly impacted them.

What went wrong, in Allen’s view, was not the institutional setup, but a failure of the respective levels of government to step up to their responsibilities and obligations. Allen’s references to Gerken put her squarely in the camp of those who reject the idea that the only version of U.S. federalism is the one that protected Jim Crow. These scholars aspire to a new vision of federalism—what Gerken calls Federalism 3.0—that utilizes the federal structure to channel and resolve collective action problems and creates greater equality in voice and representation.

For Allen, in short, American federalism is not the cause of the legitimacy crisis or the failure of the social contract, only a potential solution. But here we can begin to see the problems with equating federalism and decentralization, rather than seeing federalism as a contestation over power and the scope of national authority. In Allen’s aspirational federalism, the national and state governments would have been working toward a common purpose, with the national government “activating the ties that bind fifty states and eleven territories in support of a coordinated, harmonized, but tiered national strategy.”

But, then, why do we need federalism? A unitary system could define national standards, decentralize implementation, and even carve out specific areas of authority for the states. If the goal is to get the national government to ensure coordination and harmony of social policy, it hardly seems ideal to have a system where the scope of national authority can be regularly challenged by opponents of coordination and harmony—a system, that is, rife with veto points. A relatively high level of decentralization might be useful for implementing a national response, but it’s not clear why a federal system of any kind is necessary—let alone the messy, constitutionally contested American version.

The value of understanding American federalism as a struggle over power is that it helps us see that the very powers of the national government are themselves open to contestation. The double battleground of American federalism has long led opponents of national policy to shift the debate away from substantive policy proposals and toward the constitutional claim of a limited national government authority. In fact, it was arguably American-style federalism that facilitated state and national governments working at cross-purposes during the pandemic. Even when the national government tried to establish national standards for masks and vaccines and encourage compliance, many states capitalized on their autonomy and went in the opposite direction, with deadly consequences for areas with higher Republican vote share.

A key part of the problem was Trump’s entirely transactional response to the pandemic. But skepticism of national power facilitated, and for some even legitimated, Trump’s anemic reaction. Americans have become accustomed to the national government doing little or nothing in the wake of a crisis, from mass shootings to minimum wage stagnation. It is not enough to show that a national policy could benefit the nation as whole. American federalism allows powerful opponents of almost any national policy to claim that Congress is acting outside the scope of its constitutional authority. And the effects of federalism on our national political structure through bicameralism and equal representation in the Senate make it sometimes possible to actually block these policies. Allen’s plea that the national government focus on the “big picture” understates the fact that American federalism has long created opportunities for sustained—and frequently successful—efforts to stop the national government from doing just that.

A different president might have used his or her national authority to mobilize the federal government and its relationship with the states in more productive ways, as Allen proposes. But any activation of national authority to force states to comply with certain national standards was almost certain to bring objection and challenge in this polarized era. The lawsuits against Biden’s vaccine mandates for health care workers at facilities receiving federal funding and those for large private employers illustrate this fact. While the Supreme Court upheld the former, it voided the latter.

This arrangement helps to explain why the United States lags behind the rest of the rich democratized world in health outcomes, income inequality, and a host of other social and economic outcomes. Nearly every president since Eisenhower has tried to produce a more equitable health system that would cover all Americans—an idea that Americans have supported for seventy-five years. These efforts have been thwarted for many reasons, but at least some of them are a function of our federal system. Claims to state constitutional authority are inseparable from claims about hard constraints on congressional power and these arguments have been used to challenge, stymie, and sometimes reject national social policies on everything from social security, minimum wage, and labor relations to universal health care, gun control, and voting rights.

Of course, limiting national governmental authority is also lauded as one of federalism’s key virtues. Allen seems to want at least some assurance of a constitutionally protected sphere of authority at the state and local level to protect political minorities from the potential of exclusion and oppression in the national arena. Other advocates of federalism from the left are less attached to the concept of state sovereignty but nonetheless champion the ability of racial and ethnic minorities to hold power at the local level as facilitating a “politics of recognition.”

But here again we run into problems with the distinction between federalism and decentralization. Under American federalism, local governments have no constitutional status; they are creatures of state constitutions. Even in home rule states—states that allow municipalities to draft local charters that transfer some powers from the state to the locality—the scope of local authority can be changed by the state legislature. In fact, as cities have become the province of liberals, states dominated by conservative lawmakers have increasingly enacted pre-emption laws, limiting the scope of municipal authority on issues like minimum wage, paid leave, anti-discrimination, gun control, and even the creation of municipal broadband. And even where local governments operate in liberal states, they face extraordinary fiscal imbalance compared to the host of problems confronting them.

Perhaps most puzzling, there is nothing in the structure of American federalism that ensures that vulnerable (as opposed to powerful) minority groups will be the ones whose voices, representation, and influence are supposedly amplified in subnational governments. Some, arguably all, of the most powerful interests in American society are political minorities: the “one percent,” corporate CEOs and shareholders, and other individuals and groups with a high degree of economic resources. So, too, are white nativists, who have long sought to confine American power and citizenship to white people (or at least, the right kind of white people). As Grant McConnell trenchantly noted in his 1996 book, Private Power and American Democracy, constraining the power of the national government does not eliminate the problem of power; it simply moves it elsewhere, primarily to the private sector and regional elites.

Grumbach sheds light on this phenomenon by asking what happens when limited national government leads to more policy activity at the state level. His focus is on the past few decades of increasing political polarization and the nationalization of the political parties.

There is little doubt that polarization has increased, particularly on the right, and that polarization has largely incapacitated Congress. At the same time, political parties at all levels of government have also become more national in focus, with increasing national coordination among groups, activists, incumbents, platforms, and candidates. Grumbach argues that the intersection of these two developments—deep polarization and nationalization of parties—has transformed American federalism into a system that exacerbates, more than mitigates, the nation’s challenges. Whereas the conventional narratives about federalism highlight its capacity for participation, accountability, experimentation, and protection against oppressive power, Grumbach finds that today’s federalism is more likely to do the opposite. It reinforces and even worsens unequal political influence, reduces political accountability, and enables antidemocratic interests, especially the wealthy, to win out, despite their unpopular policies.

Grumbach begins by showing that, whereas divided government in Congress is now fairly common, partisan control at the state level has become more unified. For both Democrats and Republicans, there are almost always a few states where they have control. To study the impact of this trend, Grumbach examines interest groups, donors to state political campaigns, and state policies between 1970 and 2018, drawing on an original dataset of 135 policies across 15 issue areas: abortion, campaign finance, civil rights, criminal justice, education, environment, guns, health/welfare, housing/transportation, immigration, labor, LGBT rights, marijuana, public sector labor, taxation, and voting.

Grumbach finds that states have been very busy over the last twenty years, with policy changes occurring across all issues. But it turns out that state elections are just as elite-driven as national ones, and donors are actually more likely to be white and wealthy at the state level than the national. Contrary to the hopes of progressive federalists, it is not grassroots groups of ordinary voters (let alone the most vulnerable political minorities) that dominate state politics but rather highly organized, highly resourced activists, donors, and organizations. Policy is being changed by the parties in power, but public opinion has been relatively static on most issues. And the adoption of “innovative” policies from other states seems to occur not on the basis of their effectiveness and consistency with public preferences in the state but, rather, on whether they were implemented by states controlled by the same political party. States, in short, don’t appear to be very robust “laboratories” of democracy (as in the metaphor made famous by Justice Louis Brandeis).

Most challenging to federalism’s aspirationalists is Grumbach’s evidence of democratic backsliding. Over the past two decades, if your state was controlled by the Republican party, it likely became less democratic than the average Democratic-controlled state: more voter restrictions, more restricted access to the ballot, more gerrymandering, more disenfranchisement, more registrations rejected, fewer resources for identifying polling places, less same-day registration and absentee voting. This assault on democracy would not have been so successful, Grumbach argues, if it were not for American federalism, which structures power in ways that facilitate elite influence at every level of government. It is worth quoting him at length here:

The major crises in modern American politics are not just the result of institutional racism, plutocratic influence, or partisan polarization. They are a product of these forces flowing in a federal institutional system of government. . . . The structure and multiplicity of these venues make it more difficult for ordinary Americans to hold politicians accountable in elections. This structure is advantageous to well-resourced interests, who can move their political money and influence across venues in highly strategic ways. Federalism makes it easier for political actors to tilt the rules of American democracy, itself, to their advantage. Antidemocratic interests need only to take control of a state government for a short period of time to implement changes that make it harder for their opponents to participate in politics at all levels—local, state, and national.

Rather than enhance political accountability, then, the multiplicity of overlapping political authorities in American federalism seems to weaken the incentives of lawmakers to perform well. One reason, Grumbach argues, is that it is harder for voters to trace which level of government is responsible for what. This information asymmetry undermines the power of ordinary people but strengthens it for economic elites, whose concentrated and narrower interests allow them to sustain mobilization, propose model legislation, and get in early on blocking policies adverse to their interests. In any political system, elites have greater access to power than the masses. But the fractured landscape of American federalism provides them with many more venues than they might otherwise have.

What do we have to show for the massive social engineering states have undertaken over the last twenty years? For Grumbach, we can hardly say that the United States as a whole is better off than it was a generation ago. “Rather than ushering in democratic responsiveness, social harmony, and economic prosperity,” he notes, “the shift in policymaking from the national to the state level since the 1970s has coincided with the weakening of democratic institutions, the precipitous rise of economic inequality, and growing mass polarization and discontent.” Aspirational federalists might counter with the observation that Grumbach’s own findings show that states under Democratic control have become more progressive and, on some issues, like environmental regulation, health, and welfare, the overall effect across the country has been more liberalizing. But on other issues, of course—abortion, civil rights, guns, immigration, labor, and voting rights—the overall trend has tacked right.

This is the devil’s deal for the left that comes with American federalism. Victories in California and Massachusetts may be gratifying, but they do not solve national problems or nationwide inequality, and losses in states controlled by conservatives or reactionaries only exacerbate unequal opportunities and outcomes. Pandemics, guns, pollution, and racist groups all travel across state borders; rules about participation and representation vary widely, too. Until there were national rules with aggressive federal enforcement, fair policies on voting rights, equal protection, clean air, the minimum wage, and labor organizing—among other areas—were not safe or fully effective. (As Jamila Michener has recently shown in relation to Medicaid, for example, variation across states has a profound impact on the lives and political disempowerment of individuals, families, and communities.) Ironically, many of the policies adopted in liberal states—like legal abortion, gun safety measures, and expansion of Medicaid—are popular nationally. Championing federalism for producing innovative liberal policies at the state level overlooks the fact that American federalism may be one of the reasons why at least some of these policies do not exist on the national scale in the first place.

In a final challenge to the hopes of federalism’s progressive aspirationalists, Grumbach argues that, by creating new opportunities for the states to gerrymander, suppress votes, and diminish the power of labor unions, American federalism may have indirectly contributed to the rise of Trump, rather than served as its antidote.

Maybe a different vision of American federalism, like the one Allen and other progressive federalists imagine, is the answer. But Grumbach is not alone in finding that the structure and complexity of American-style federalism seems to benefit powerful elites more than ordinary people, no matter how much we may wish it were otherwise. In the United States, federalism has always been a battleground over the nature of American democracy itself—who gets to participate, to decide what we, as a nation, will be and do. As promising as it sounds in theory to diffuse political authority through multiple locations where different groups can engage in political combat and find common ground, the messy landscape of American federalism has often functioned to limit democracy rather than expand it, and to empower already powerful elites rather than restrain them.

Indeed, the most significant achievements of social, economic, and racial progress in the United States have been driven by mass democratization and the nationalization of social policies. The Civil War, the Progressive Era, women’s suffrage, the New Deal, the social movements of the 1960s and ’70s: all exhibit this pattern. In this sense, Americans have been trying to extricate themselves from federalism for the past 150 years. As a matter of governance, the transformation of the United States into a more equitable and democratic nation has mostly come from “forceful federalism”—the direct intervention of a robust and effective national government. And forceful federalism, in turn, has primarily come from social movements winning national elections.

Progressive federalists would be right to point out that many of these movements began at the state level and that it wasn’t until the pressure bubbled up from below that at least one national party chose to embrace them. But there is a difference between parlaying state and local efforts into national victories and doubling down on state constitutional authority. The former doesn’t require championing federalism so much as exploiting its structure for realpolitik. The latter risks reifying the worst features of American federalism: arbitrary limitations on the scope of national authority, asymmetry of information and reduced democratic accountability, and the right of states to exclude, marginalize, and even kill their own citizens. Since progressive victories have generally meant overcoming federalism, it is not surprising that a major tactic of opponents of progress has been to champion federalism’s limits on national power and the virtues of state governance.

This is not to say that progressives—or any Americans interested in moving beyond the status quo—should ignore state and local politics, of course; Grumbach’s own analysis, and rulings like Dobbs, make clear why they cannot afford to. But to secure multiracial democracy and reduce inequality, progressive strategy must also not lose sight of the imperative of forceful and effective national power.