With the announcement last week that Attorney General Eric Holder has authorized federal prosecutors to seek the death penalty against alleged marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the city of Boston is once again roiling over his case.

Mayor Marty Walsh reiterated his past opposition to the death penalty, while also saying that he respects the federal process over which he has no authority. Ed Davis, who was Boston’s police commissioner at the time of the attack, which killed three people and maimed dozens, supports Holder’s decision. The Globe editorialized against the move, as has Carol Rose, executive director of the Massachusetts ACLU.

“Victims, first responders, spectators, runners, and others profoundly affected by the attack last April responded with mixed feelings about the decision,” wrote Globe reporter David Abel. A poll last September found that Boston residents, by a 57-33 percent margin, prefer a sentence of life imprisonment without parole.

It was inevitable that the prosecution of Tsarnaev, who is also charged in the killing of MIT police officer Sean Collier, would be swept into the long-running American struggle over capital punishment. If Holder had not pursued the death penalty, then its supporters would have cried out at the perceived injustice.

So now it is opponents’ turn. Rose puts it bluntly, “Vengeance is not justice.” That sounds good but also denies the intimate relationship between criminal adjudication and payback. It is a facile assertion, easily deployed on both sides of the issue. As President George W. Bush remarked after the 2001 execution of Timothy McVeigh, “The victims of the Oklahoma City bombing have been given not vengeance but justice.”

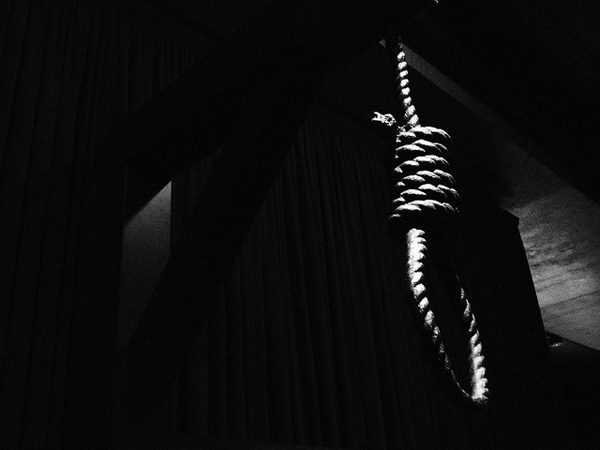

To supporters of the death penalty, it is obvious that an eye must be traded for an eye, although to opponents, it is equally obvious that we are compelled to turn the other cheek—to show mercy, if not complete forgiveness. The primary moral guide of America’s largest religious groups provides little help.

It may be more useful to think about the death penalty in pragmatic terms. What does it gain us, and what do we lose?

One benefit is leverage. In Tsarnaev’s case, prosecutors may be using the capital charge to obtain a guilty plea in exchange for the “lenience” of life without parole.

And arguably the execution of the offender provides solace to the families of victims as well. But, as Abel’s report describes, they may be divided in their opinions. In any case, the misery of aggrieved families is, at least officially, not part of the sentencing calculation.

The practical downsides of capital punishment are considerable. One is the possibility of an irreversible error, a famous instance being that of Cameron Todd Willingham. The justice system makes a lot of mistakes. As BR contributor Beth Schwartzapfel reported in Mother Jones, “A conservative estimate is that 1 percent of the US prison population, approximately 20,000 people, are falsely convicted.” She points out that in Texas, where Willingham was executed, Governor Rick Perry has presided over five death row exonerations. The Death Penalty Information Center notes increasing rates of death row exonerations in the new millennium, perhaps due to the availability of DNA evidence. How many innocents have fallen through the cracks?

Then there is the well-known expense of capital punishment. Housing a criminal for life isn’t cheap, but it is cheaper than execution, thanks in large part to the costs of appeals and the lengthy prison stays of death row inmates before the final day comes. In 2013, there were 3,108 inmates on death row, but only 39 executions. (For some revealing numbers on costs, see the Death Penalty Information Center link above.)

Pam Karlan, formerly BR’s legal columnist, now with the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, offers an important but underappreciated pragmatic argument against capital punishment: it distracts the most able and talented members of the legal profession from critical work on behalf of non-capital defendants. “The concentration on capital cases comes at a cost,” she writes. “Ineffective trial lawyers, inconclusive evidence, inconsistent testimony, and impenetrable procedural thickets are hardly unique to capital cases,” but the best and brightest commit their attention to these cases and their many appeals. Ohio State legal scholar Douglas Berman “has calculated that about one in ten thousand state felony sentences is a death sentence, yet the [Supreme] Court devotes more resources to reviewing death sentences than to reviewing claims in all other criminal cases combined.”

Statistics are straightforward, but we also have to reckon with the unquantifiable: the moral callousness reinforced when a state kills its citizens in pursuit of justice. Only with execution as the loftiest punishment could life imprisonment without parole seem like indulgence. Proponents of the death penalty chastise their opponents for being soft, yet granting mercy is among humanity’s hardest tasks.