History does not repeat itself, even if it sometimes rhymes. But, as the president calls for 15,000 new ICE and border patrol agents to bolster an already hypertrophic deportation machine, it is worth pausing to reflect on an earlier moment of fugitivity and federal power, of crisis and resistance: the years following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

The resistance had its roots decades earlier, when a despised and subordinated minority—northern free blacks—inspired the enduringly unpopular interracial social movement called abolitionism. That movement formed a periodic, conflict-ridden coalition with a much larger group of whites who opposed the extension of slavery but did not seek its abolition. The radicals drove the non-radicals steadily forward in defense of fugitive slaves, defying both federal law and the warnings of the major political parties. In some places, such as Boston, that defense and the federal reaction to it were so fierce that it gave birth to a new politics of race, slavery, and freedom.

Free black people of the mid-nineteenth century prefigured the struggles of later generations of “alien citizens.”

That history is over. It cannot directly shape how a resistance movement behaves today. But an account of its roots, complexities, and achievements may suggest how radicals can shift the field of political play and debate in their direction, pursuing their goals while persuading the persuadable. At the very least, it is one of the United States’ great freedom songs. It may do us good to learn the words.

• • •

The struggle of the 1850s began in and drew its animating energy from African Americans’ analysis of their own circumstances. Slavery hung a shadow over the lives of free black people, even in places where slavery had long been legally abolished, such as Massachusetts. There, African Americans possessed nearly every formal right on the same basis as the “free white persons” legally eligible for immigration and naturalization. But African Americans commonly experienced northern freedom as mocking, hostile, and violent. For the fugitive slave Frederick Douglass, liberty in Massachusetts included a constant, oppressive awareness of being perceived as an inferior. “Prejudice against color is stronger north than south,” he declared; “it hangs around my neck like a heavy weight. . . . I have met it at every step the three years I have been out of southern slavery.” Even in Massachusetts, African Americans were barred from nearly every avenue of economic or educational advancement. Railroad companies segregated black passengers in Jim Crow cars, a policy their conductors enforced with violence. State officials ejected free blacks from official processions, and ruffians chased them from Boston Common. The foremost form of popular entertainment, the minstrel show, mocked their appearance and aspirations. No wonder northern black activists bleakly called themselves “the nominally free,” or “the two-thirds free.” One African American newspaper was entitled the Aliened American.

In this sense, the free black people of the mid-nineteenth century prefigured the struggles of later generations of what historian Mae Ngai calls “alien citizens.” Ngai’s analysis reveals how the U.S. citizenship of native-born Americans of Chinese, Mexican, Japanese, and Muslim background has in practice been limited or nullified by what many consider to be their unalterable foreignness. The radical black activists of a century and a half ago well understood that their compatriots regarded them mainly through the prism of their racial association with slaves. So it has been since, for Chinese Americans figured as unassimilable aliens, Japanese Americans assailed as members of an enemy race, Mexican Americans dubbed “illegals” and rapists, and Muslim Americans branded terrorists. Even those formally vested with citizenship cannot escape the gravitational drag of their racialized association with a dangerous and foreign otherness. Even the mildest formulation of alien citizenship tells the tale: “Right, but where are you really from?”

Within the coalition, radicals drove the non-radicals, many of whom were most concerned about slavery’s threat to their own liberties.

Instead of seeking to overcome their association with slavery, antebellum African American activists built their activism around it. Defiantly dubbing themselves “colored citizens,” they pursued twin and inseparable projects: freedom to the slave and equal citizenship for all. Some embraced this course because they had been slaves themselves. Others did so because they understood that they could only escape from slavery’s stigmatizing shadow by asserting their common unity, dignity, and equality.

In one sense, the conditions of black freedom left them no choice. Most states that had abolished slavery did not require black people to prove they were free. But the U.S. Constitution’s Fugitive Slave clause curtailed this presumption of freedom. In theory, a 1793 law that gave teeth to this clause provided only for the capture and return of escaping slaves. But the law did not guarantee those accused of being fugitives the right to testify in their own defense, which made it quite possible to enslave a free person. Nor was this the only existential risk free black people faced: the demand for slaves birthed a kidnapping industry with hundreds (possibly thousands) of victims, among them Solomon Northup, who authored Twelve Years a Slave (1853) based on his experience of being illegally enslaved.

The “colored citizens” built their politics on broader solidarities than the fear of kidnapping. They understood that their struggle required powerful allies—God, certainly, but also concert of action among African Americans, and, in a region where they formed a tiny minority of the population, white allies as well. So they extended their hands in two directions. They built a black counter-public of churches, schools, lodges, and literary and burial societies in which they could secure their own ends in conditions of dignity. But they also repeatedly reached out, insisting on their equal status in the broader world and seeking white allies to help them achieve that. As the firebrand Boston activist and pamphleteer David Walker put it in his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens (1829), “what a happy country this will be, if the whites will listen.”

A few white men and women did. In the 1830s a new wave of interracial abolitionist societies and a newspaper, the Liberator, began to promote both freedom and equality. Over the following decade this movement—small, radical, socially anathema—became such a powerful force for propaganda, petitioning, and the defense of fugitive slaves that it engendered a fierce and often violent backlash across the North and South.

The radical claims of abolition and equality could not move white-supremacist political majorities in the North, but the illiberal injustice of unlawful enslavement did. During the 1830s and 1840s, many northern states passed “anti-kidnapping” or “personal liberty” laws. Some guaranteed rights to the accused, especially the right to testify; others barred state officials from participating in forcible renditions. Inspired by abolitionist activism but drawing on a broader though attenuated antislavery sentiment, these laws began to set limits on slaveholders’ ability to reclaim their fugitive property.

Massachusetts’s personal liberty law was the product of radical resistance inspiring liberal proceduralism. It had its origins in the year 1842, when black and white Bostonians thwarted the rendition of a fugitive couple, George and Rebecca Latimer. Hundreds of black protesters filled the streets between the courthouse where George Latimer was examined and the jail where he was held, and some tried to free him as he passed. Antislavery lawyers pressed every angle of a possible defense, winning a crucial delay, while several young white men of means started a newspaper dedicated to the cause, thus keeping the controversy in public view. Others brought political pressure to bear on the city jailor. Soon the Latimers’ owner capitulated, selling them at a loss. But freedom for the pair was not the end of the story: activists used the attention created by all of this violence, maneuvering, and propaganda to gather tens of thousands of signatures on two petitions—one to Congress, asking for laws and amendments that would insulate Massachusetts from the fugitive slave law, and one to the state legislature for a law barring state officials from participating in renditions. The latter became the state’s 1843 personal liberty law.

Alone, neither crowd action, legal stratagem, propaganda, nor petitioning could have secured the Latimers’ freedom and then turned that into a broader political victory. Together, they did. Crucially, as today, this concert did not require explicit agreement among the diverse participants. Some sought to influence the major political parties, while others saw the Constitution itself as corrupt. Some denounced the use of violence, while others celebrated it. One faction of abolitionists howled against another’s paying “ransom” for George Latimer’s freedom. The movement had many parts, and they did not have to agree on all points in order to create effects that most desired.

But in the national political field, moral sympathy turned out to be no match for political ambition and capitalist expansion. In the midst of a struggle over the status of slavery in the vast territories wrested from Mexico in 1848, slaveholders were able to demand a new, stronger fugitive slave law that gave them potent new weapons: a new system of federal tribunals for fugitive-slave cases; a streamlined hearing and rendition process that granted no rights to the accused; and stringent criminal penalties for attempting to obstruct the return of a fugitive. Worse, these mechanisms were promoted as part of a national compromise to ensure peace between the slaveholding and non-slaveholding interests of the nation. To defy them was to threaten national unity.

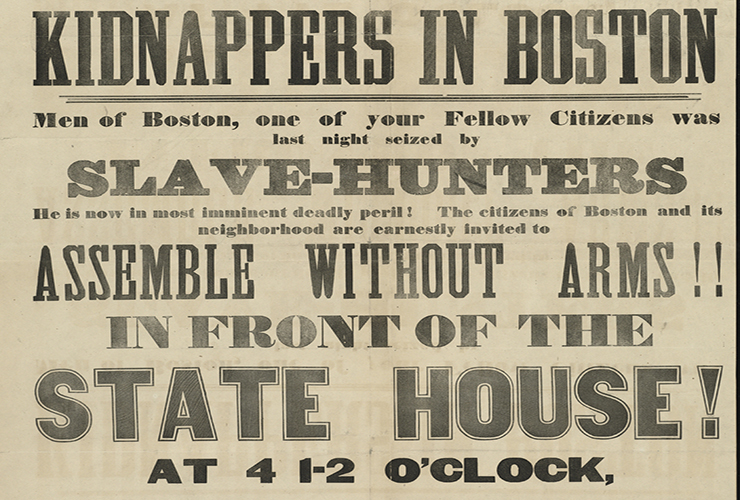

There were always a few white people who were willing to flout the law, but the concerted, mass resistance began in the black community. As federal marshals and private slave hunters began pursuing fugitives through the streets of Boston, a meeting of the city’s black activists swore “to resist this law, rescue and protect the slave, at every hazard.” Over the next few years, they brought their white allies along, managed the day-to-day work of keeping the movement together, and produced spectacular public collisions that forced the federal government to react—and finally to overreact. If black resisters did not quite make Boston and other cities “Canada to the slave,” they expanded these spaces of refuge, in reality and in political imaginations, until they reached whites who cared not a whit for abolition or for African Americans generally.

Much of the work took place behind the scenes, in the boarding house of former fugitives Lewis and Harriet Hayden, in incessant meetings and fundraising efforts, in the gathering of signatures and posting of notices. No movement succeeds without these daily labors. But far more visible to people beyond the movement’s core were the spectacular public defenses, rescues, and attempted rescues of fugitives in Boston in the early 1850s.

Sometimes the victories were clear-cut. In the defense of fugitives William and Ellen Craft, the movement’s entire repertoire of strategies came to bear on the two slave-hunting agents sent to retrieve the self-liberated pair. In the end, the slave hunters were driven from the city by crowds of black protesters, abolitionist lawyers, and a militant minister who plainly threatened that their lives would be in danger if they remained in the city. The Crafts then fled to greater safety in England; British domains were the era’s only truly reliable sanctuary for American slaves. The Crafts were only the first. In February 1851, when a fugitive named Shadrach Minkins was arrested and hustled into a fugitive-slave commissioner’s court, lawyers, ministers, and a crowd again quickly mobilized. Lawyers delayed the proceedings, which allowed the 1843 law to come to Minkins’s aid: court officials, fearing prosecution and the loss of their positions if they assisted in a rendition, refused to lock him in the jail. As a result, during a brief adjournment he was held in the much less secure courtroom. This gave other activists, including Lewis Hayden, the opening they needed. They forced their way into the courtroom and literally carried the fugitive to a waiting carriage. Men and women sheltered and guided him through and beyond the city, and within days he was safely in Canada. When the conspirators were tried, antislavery-minded men ensured hung juries, freeing Hayden and a half-dozen more black and white conspirators.

To prevent the rescue of an escaped slave, the court house was surrounded with a heavy chain. It was an irresistible image: justice in chains, and judges bowing beneath it to enter their own courthouse.

The backlash to these thwarted renditions, like today’s nativist politics, portrayed the subordinate group’s challenge as a racial threat to national identity. In response to Minkins’s rescue, the fugitive-slave commissioner in Boston described the rescuers as “levying war” on the United States. The leading figures of U.S. politics agreed. Henry Clay took to the Senate floor to vent his anger at this “outrage,” the work of “African descendants . . . people who possess no part, as I contend, in our political system.” Massachusetts’s own Daniel Webster, the secretary of state, called the rescue “treason.” A newspaper allied with the administration pulled out all the stops, screaming the headline “OVERTHROW OF THE WHITE POWER AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE BLACK EMPIRE OF MASSACHUSETTS!”

To overthrow the republic that explicitly defined itself as white was indeed activists’ goal, but their public counterargument to this black scare focused instead on white vulnerability. Ten years before, the white editors of the newspaper dedicated to the Latimers’ defense frankly avowed that “We do not exist therefore out of compassion for Latimer, but out of compassion for this community,” and that the case exposed “the insecurity of the liberty of all of us.” This argument surged to the fore in the 1850s, and many radicals accepted its power even when they did not agree with its moral logic. They simply pointed to what their enemies were doing. In order to prevent the rescue of another arrested fugitive, Thomas Sims, authorities surrounded the Boston Court House with a heavy chain. It was an irresistible image: justice in chains, and judges bowing beneath it to enter their own courthouse—the white polity of the city abased before the “slave power.” As authorities ratcheted up their preparations and safeguards in response to the very real threat of a forcible rescue, they confirmed what African Americans had said first, what white abolitionists had then proclaimed, and what even non-egalitarian antislavery forces were now saying: slaveholders were tyrants who would exert their will wherever they could.

Beyond the radical core of the movement, a broad and attenuated array of supporters was gathering. Some felt sympathy for fugitives without embracing the movement’s activism or its egalitarianism. Others perceived abolitionists as allies only in the sense that they both opposed the ambitions of the slaveholders. A larger number, still politically inarticulate and in no meaningful sense abolitionist, were coming to feel that slavery now somehow threatened their own liberties.

In 1854 this political situation turned apparent defeat into the movement’s most important victory. When the fugitive Anthony Burns was arrested and imprisoned in the Boston Court House, thousands of people attended meetings and rallies, including in Faneuil Hall; the entire city was preoccupied with the affair. A few days after Burns’s arrest, a band of militants, including Lewis Hayden and the white radical minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson, attempted to break into the building to free him. In the course of their unsuccessful assault, they shot and killed a deputy marshal and were forced to flee.

It could have proved to be a debacle. Instead the failed and bloody raid, capping the persistent challenges of the prior four years, provoked the federal government to an unprecedented show of force. Calling out the city police, the state militia, and federal troops, authorities formed a phalanx around Burns and marched him with rifle and cannon from the courthouse to the wharf, where a ship waited to return him to slavery. Across a suddenly wide swath of opinion, the federal government had gone too far in the service of protecting slavery, and confirmed what to many people had long seemed to be a hysterical fear of the “slave power.” Here it was, plain as day, enforcing the law of slavery in Boston.

The display of force backfired spectacularly. Thousands lined the streets to jeer and protest the parade of soldiers. Law and newspaper offices draped their buildings in black crepe, or flew the U.S. flag upside down. Walt Whitman, no friend to abolitionism, wrote a scathing poem in which the specters of the Revolutionary dead came clattering to life to chastise the men marching Burns to slavery. In the days that followed, white men across the state formed “Anti-Man-Hunting Leagues,” which held drills to prepare for confronting slave catchers wherever they next appeared. The legislature soon overrode the governor’s veto to enact a vigorous new personal liberty law, modeled after the 1843 law but with sanctions aimed directly at countering the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. The industrialist Amos Lawrence declared that he and his peers “went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs, and waked up stark mad abolitionists.”

He exaggerated. Such men’s commitments to equality remained vague and dim. A few years later, when confronted with the possibility of losing their profitable trading relationship with the slave states, many hastily backpedaled toward appeasement and compromise with slaveholders. But although the movement’s core remained small, that group had changed the field of play. It galvanized potential allies into supporters, and brought concerted, militant resistance to the slave power—even when represented by the federal government—into the mainstream of political debate.

Although these core resisters did not know it, they were also building the road to the Civil War. When South Carolina seceded in December 1860, the legislators’ account of their grievances read like a list of the northern freedom movement’s accomplishments: personal liberty laws, fugitive rescues, abolitionism, and free black claims to citizenship. Secessionists, exhausted and enraged by free blacks and northern radicals, their sanctuaries and their coalitions, struck for slaveholding liberty. The black and white activists who inspired them did not know they were lighting that particular spark, but when the war came they continued their work. Their struggles, and those of southern slaves, transformed the suppression of a rebellion into a war of emancipation. Before long, many white northerners found themselves ready to take that leap as well.

History is neither a map nor an oracle. We are often called to embrace Seamus Heaney’s stirring invocation of its possibilities, that “once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme.” But justice, like history, is neither a tidal wave, nor a tendency, nor a once-in-a-lifetime event. Justice is deduced by people from their circumstances, and brought into being by their actions. That is in part how history is made as well. That is why the people on the frontlines of the struggle, people such as Lewis and Harriet Hayden, demand our attention. Perhaps a moment is before us when that call and response between radical activists and a broader public can build and grow. Whether the transformative achievements of a small band of radicals a century and a half ago can inspire and encourage today’s vision of ever-expanding sanctuary remains to be seen. In any case, as the Haydens well understood, neither the lessons nor the cycles of history will dictate the outcome.