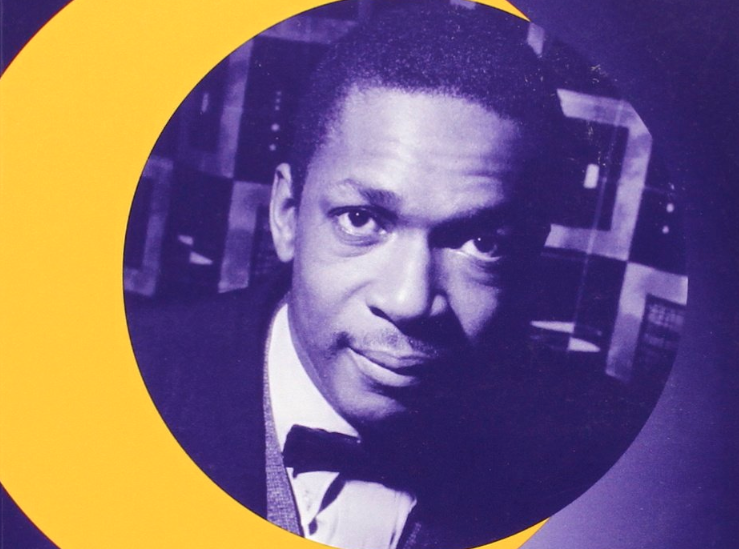

John Coltrane: His Life and Music

Lewis Porter

University of Michigan, $29.95

The John Coltrane Companion: Five Decades of Commentary

Edited by Carl Woideck

Schirmer, $15

On a 1966 tour of Japan, when asked what he wanted to be in ten years, saxophonist John Coltrane replied simply, “I would like to be a saint.” Coltrane died a year later but he succeeded in his ambition. It is no coincidence that the plaque marking his Hamlet, North Carolina, birthplace calls him a “Jazz Messiah,” or that the African Orthodox Church canonized him after the appeal of St. John’s, a San Francisco storefront church which for the last three decades has used Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” as the basis for a saxophone-charged Sunday morning liturgy. Coltrane’s music, especially at its most avant-garde, is sacred music.

At the height of his career in the late fifties and early sixties, Coltrane served as jazz’s pilgrim, infusing the music with a spirit of technical and moral perfectionism. His sound fulfilled that period’s hunger for a style that could combine meditation and militancy, discipline and liberation. Like Martin Luther King Jr., he emphasized the spiritual constancy in the quest for freedom. At the same time his music, which roiled and shifted from album to album, was a prescient artistic illustration of Malcolm X’s call for freedom “by any means necessary.” These two main ingredients—religious gravity and principled errancy—were the basis for the alchemy in Coltrane’s “classic quartet,” which balanced his saxophone’s preacherly exhortations with bracing bass-piano vamps.

Lewis Porter’s John Coltrane: His Life and Music tracks the self-effacing Coltrane with a gumshoe’s tenacity and a scholar’s understanding. The first full-dress Coltrane biography in 25 years, it highlights the musical innovations that spurred his progress from idiosyncratic sideman to exemplary World Music pioneer. Like The John Coltrane Companion, a valuable omnibus gathering of profiles and interviews, it is strong in biographical detail but less interested in the larger puzzle of Coltrane’s impact—how his music tapped into, and redirected, broad currents in black and American life, from civil rights and evangelicalism to the rise of the concept album. Still, no book better captures the spirit of the man who guided jazz through an epoch of giant steps.

Like many hard boppers, Coltrane was born into the segregated South, migrated to the North, and then made music that keyed into the new dilemmas of urban life. Growing up in High Point, North Carolina, in the 1930s, he benefited from a family with interests in music and the ministry. His mother sang and played piano; his father, a tailor, played clarinet and violin. But the true paterfamilias was Coltrane’s maternal grandfather, a Methodist minister who impressed young John with his militancy. During seventh grade, Coltrane’s fortunes took a tragic turn. Within six months, his maternal grandfather, father, and maternal grandmother all passed away, and John became tortured by his inability to remember what his father looked like. In this emotional vacuum, Coltrane threw himself into the clarinet and alto sax.

When his family moved to Philadelphia in 1943, Coltrane found himself in a cauldron of jazz camaraderie and a central breeding ground of the hard bop style. He soon began a journeyman’s life, gigging with cocktail trios and R&B combos. How did this Coltrane grow to become the heavyweight champion of his later years? Porter and The John Coltrane Companion both provide the obvious answer: practice. At the Granoff Studios in Philadelphia, where he took a full course of music theory and lessons funded by the G.I. Bill, Coltrane arrived early in the morning and remained through the evening. As the night wore on, he would finger but not blow into the instrument so that he could quicken his reflexes without waking his neighbors. Coltrane’s perfectionism was legendary. After arranging a big band piece, “Nothing Beats a Trial But a Failure,” he listened to one performance, then quietly dumped all the hand-copied sheaves of music through the grates of the gutter. The piece’s title had said it all.

But Porter also uncovers a less obvious source for the saxophonist’s stylistic originality. Coltrane learned from traditional classical exercises, which produced unforeseen difficulties—and unforeseen technical resources—when transposed from piano to saxophone. Borrowing exercises from a band pianist, he stunned fellow musicians by forcing his fingers to navigate arpeggios, trills, and wide leaps in melody. Meanwhile at Granoff he discovered world-music and ultrachromatic scales. Though Coltrane would eventually be heralded as the avatar of a new black aesthetic, much of his style evolved out of his fervent search to master all idioms, including those outside the scope of his instrument or of jazz itself.

In 1955 his career took off. Trumpeter Miles Davis hired Coltrane into his quintet, gambling on a 29 year-old with a jagged style and a heroin habit. The quintet’s albums-most famously Round About Midnight and Cookin’-were landmarks of musical interplay, but Davis grew aggravated with Coltrane’s unreliability. At one low point, Coltrane and bassist Paul Chambers checked out of a St. Louis hotel through a window. In 1957 Davis fired the saxophonist.

The dismissal was a shock and goad to Coltrane’s career. In its aftermath, he experienced what he called “a spiritual awakening” and quit drugs and alcohol. Under the influence of pianist Thelonious Monk, Coltrane started obsessing over harmonic variation and his solos grew longer and longer. “I would go as far as possible on one phrase,” he said, “until I ran out of ideas.” His style was dubbed “sheets of sound,” as he strung together arpeggios so dense that his saxophone seemed to play many notes at once.

As a composer, he became a virtuoso of feverishly paced harmonic complication, his experiments culminating in the title track of 1959’s Giant Steps. An etude built upon third-related chords, “Giant Steps” was an improviser’s obstacle course; its underlying scales churned at a dizzying rate, guided more by mathematical formula than the single modality of the blues. The album was a great success, but Coltrane himself was dissatisfied. “I’m worried,” he said, “that sometimes what I’m doing sounds just like academic exercises, and I’m trying more and more to make it sound prettier.” That same year, Coltrane found that new direction through his renewed collaboration with Miles Davis. Davis’s “modal” jazz—famously emerging on Kind of Blue (1959)—hung on one scale and left the improviser to superimpose a wide variety of chords upon this fairly static harmonic framework. If “Giant Steps” had shifted its underlying chords every half-measure, Davis’s “So What” gave an improviser sixteen measures to explore a single scale and stack harmonies on top of the rhythm section. With modal forms, Coltrane found a way to combine side-slipping chromatic movement with more lyrical lines. The end result was the sound of searching: a saxophone flitting, hovering, baiting the rhythm section, then colliding with it head-on in a moment of harmonic convergence.

During this period, Coltrane traded a riddle with fellow saxophonist Wayne Shorter: How could you start a sentence in the middle, then come to the beginning and the end at the same time? Coltrane’s 1960s “classic quartet”—Coltrane on tenor and soprano sax, Philadelphians McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison on piano and bass, and drummer Elvin Jones—offered an elliptical answer. In “Chasin’ the Trane” (1961), Coltrane launched the piece in mid-sentence with his solo, a series of disparate squawks and pulsating lines that spoke to an entrapped intensity. Only at the end of a 15-minute solo—his sinuous lines shadow-boxing with Jones’s shifty, hammering accents—did Coltrane explode onto a hummable lead melody. The piece was an exercise in spiritual and musical reorientation. Said Coltrane, “I used to listen to it and wonder what happened to me.”

Not everyone was impressed. Critics called Coltrane’s music “anti-jazz” and lambasted the anger in his style. There was some justice to their reproach. Coltrane stripped jazz of many of its ironic devices. His favorite musical genre, as seen on signature compositions like “Blue Train,” “Mr. P. C.,” and “Equinox,” was the minor blues. His hard tone and on-the-beat accents had little in common with, say, the teasing, understated phrasing of his swing hero Lester Young. He rarely stitched quotations from popular songs into his solos; his desperate interiority had little room for such playful influences. His musical seriousness was extreme: he reportedly loved the Marx Brothers movies, but only because he was intrigued by Harpo’s harp playing.

His greatest popular successes offered sweet relief along with this intensity. My Favorite Things (1960), which reintroduced the soprano sax to jazz, had a bouncy lilt that came from its waltz-time and an optimism that shone through its second mode, structured around a bright major vamp. The album went gold. A Love Supreme (1964), meanwhile, modeled the pursuit and achievement of spiritual deliverance. A jazz blockbuster—over a million copies sold—it solidified Coltrane’s persona as a musical theosophist, and more than any other album broke down the lingering division between black religious music (gospel) and the devil’s music (jazz, blues, and R&B). In one of jazz’s defining moments, Coltrane conjugated its leading four-note motive through every register and key, then gravitated back to the original key to chant the four-syllable mantra, “a love supreme.” As Porter suggests, the piece offered a startlingly rudimentary and profound exposition of God’s presence-in every space, expected and unimagined.

After A Love Supreme, Coltrane went further than his bandmates would follow. His music became even more exploratory, dropping the rhythmic pulse that had structured even his most wayward previous ventures. Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner departed the fold; Coltrane began bridging out to a new generation of free jazzers—Pharaoh Sanders, Archie Shepp, Rashied Ali, his new wife Alice Coltrane—that he had inspired. Coltrane’s critics were not far off when they said that his twenty-minute solos sounded like a musician practicing with himself: his style had always represented the thrills and the perils of autodidacticism.

And then, on July 17, 1967, he died of liver cancer. For the jazz world, his death was like so many other mysterious, sudden disappearances across the sixties: Lumumba, the Kennedys, Malcolm, and King. He had been one of jazz’s great consensus-builders, a charismatic presence who had fused the religious and aesthetic demands of the music and in the process satisfied black activists, discriminating critics, and soul searchers of every stripe. Despite his lack of humor, Coltrane radiated optimism, a faith in the power of self-seeking. In his absence, the promise of deliverance dimmed.

Porter’s biography is indispensable and long overdue. Judicious in its appraisals, it fleshes out the man and explores his art with great sensitivity. Together with The John Coltrane Companion, it will lay the groundwork for future Coltrane studies, which may tackle front-on the enigma of his popularity—how he magnetized such a broad spectrum of enthusiasts at a moment when jazz’s foothold was being ceded to soul music and rock and roll. “All musicians are striving to get as near perfection as they can get,” Coltrane said in a late interview. “To play truth, you’ve got to live with as much truth as you possibly can.” That directive may ring old-fashioned, even banal, to contemporary ears, accustomed as we are to the ironies of art and commerce. But Coltrane’s genius was to clutch innovation—a sign of hope—out of such searching simplifications.