Poetry is a thing I cannot live well without—it is one of the ways we love ourselves best, as both readers and creators of it. I have come to count on poetry. The poetry of b: william bearhart teaches me something about my easy-to-hurt heart and this unreasonable world. When I read his poems, I feel: Yes, pain, and also love. The native body, like any brown body, deserves to be loved, is capable of loving, has in it the capacity for tenderness, desire, and pleasure in a way that literature has often denied it. In “I Cast It Away, My Body:” and the other poems in this sample of his work, bearhart leads readers to the war grounds many of us wander as we attempt to recognize our bodies and lives as beautiful, even joyful, though flawed and aching. His speaker’s tenderness—for a brother, for a father, for a people—moves into and beyond the prescribed native body until it is cast away. The people in his poems are freed into the new and ancient bodies of a dragon, the earth, a dandelion, a sunflower that is also a lion. True, bearhart’s images of darkness are as infinite as the night, as the universe even. True, also, that his images of light are equally immeasurable and unyielding, such as the net which almost hangs a psychiatric patient or the welding arc in an auto shop. Yes, darkness, bearhart’s poems say, but also and always light.

—Natalie Diaz

I Cast It Away, My Body:

after Georgia O’Keeffe’s First Drawing of Blue Lines, 1916

Because two brothers make a body where none existed

God drew two bodies as one went crooked

There is a war between us. And I am losing

My brother, fabulous night panther & copper-horned

Struck by lightning, electric blue: two lines

My father pulls two ribs and one snaps into angles

In the waiting room, a body begins to fold in on itself

A body begins to pull a breathing tube from out of itself

There is a war between us. And I am losing

My brother, all copper feathers and dragon tail, chosen

In the mud of a battlefield, you’ll find my heart

Buried in the soft red clay, my body

Broke and anchored to this earth, a bolt

Jettisoned, my brother is my father’s first son

*The title is taken from an Ojibwe war poem

Heavy-headed Sunflower

after Dana Levin’s “Field”

You watch from the window

as I run to a patch of sunflowers

Or maybe I am running out of the house, around the garage, into a patch of

sunflowers,

when I run into a lion

Beautiful yellow petals,

lush golden mane,

inflorescence of a jaw, unhinged,

blooming toward a cloudless blue sky

An annulus of yellow teeth,

a ring of yellow flame burning around the neck,

corona of eclipse

We’re confrontation of sun and moon

You,

standing in the window

of this birch skin house,

me, a sunflower, neck bent and heavy-headed

.

Can you see the seeds being shook from this jaundiced eye that never blinks?

Or are you closing the shutters, do you think it is rain?

Psych Ward Visitation Hour

For 7 days and 7 nights, I’ve been shooting free throws

The doctor said I needed focus

There is no net because some guy tried hanging himself from it

But the moonlight betrayed him

In the courtyard where we sit, a dandelion grows

I see you’re uncomfortable. Ignore these

blood-brick walls, cemented ground, nurse station window

There’s forgiveness here. And I need to apologize

You’re seeing me in these weed-green scrubs, bone-cloth robe

I unscrewed the roof from our home

swallowed all the memories

Did I tell you the cops wrote “superficial cuts” in their report?

They didn’t understand when I said

I needed something red. They didn’t understand when I said

I needed to paint my chest vermillion

I’m scared to go home. Have I told you that?

I’ve always been

I keep having a nightmare where my hands grow into copper antlers

I keep having this nightmare where I hold

a dandelion in one hand, a robin in the other

I made you something during craft hour. A paint-by-numbers thing

Two deer in a winter forest full of birch trees

Look, a tiny spot of orange. Hunter orange

Blaze orange. See the buck? His antlers are still velvet

See how strong he’s standing? No, wait

his right front leg is soft on the ground. No

He’s not standing, he’s kneeling. Only,

He’s not kneeling

He’s fallen. Notice

There’s only one deer now and he’s still

His tongue juts from the corner of his mouth

His eyes are focused on me

Wait, his head is missing. The antlers are gone. Everything

Is gone. There’s a bright streak

of red screaming across the snow

There are only shadows now and boot prints. There’s only snow

I made you something during craft hour

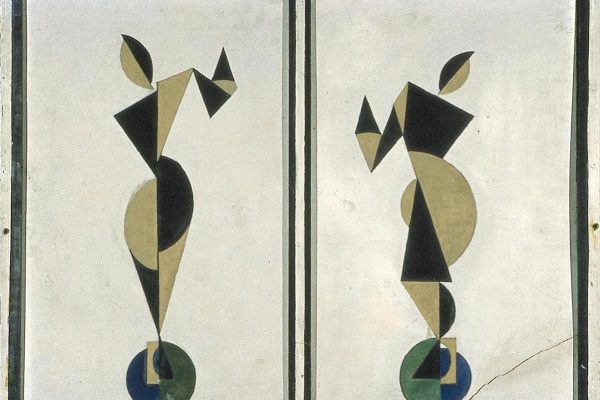

A cheap paint-by-numbers rip-off of O’Keeffe

A forest of birch trees but the math of it all didn’t make sense

So I painted the numbers blank, then left

I couldn’t focus so I went and shot free throws

I thought about the man who tried hanging himself

How afraid he must have been about going home

That dandelion is his ghost. His head

A thousand yellow florets, burning. The sun

Never felt so good. I’m glad you’re here.

When the night unravels this night becomes

a thread of moon undressed

between cotton sheets my body undressed & compressed

beneath your shadow

your shadow in the auto shop’s locked-door backroom

pants around ankles light blasting from arc weld

I shut my eyes and count asteroids in the night.

I sigh Dear sky, find some other place to fall

12-year-olds in lilac bush whispering big bangs

soft bloom of petals now knocked loose, they fall

behind the movie theater after TMNT II: The Secret of the Ooze,

we’re surrounded by stonewashed, cuffed jeans tapering

toward the center of the universe, explosion

now dust settles,

Challenger explodes all over the television

I’m eight and naked in a closet

trying on my mother’s vintage prom dresses

a thread of yellow tucked into my Hanes

because I can’t make sense of this mess in my head

and I am four years old

in my sister’s pink tulle tutu and much-too-large tights

dancing in the kitchen with the grace of a drunk

Dear universe,