The Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection and due process clauses are never far from the news. The ongoing federal marriage-equality litigation lies at their intersection. Many transformational events of post-Reconstruction America, from the dismantling of Jim Crow and the protection of reproductive autonomy to the Supreme Court’s decision in the 2000 presidential election, would have been impossible without them.

But recently two less familiar elements of the amendment—its citizenship clause and its public-debt clause—have taken center stage. Efforts to twist these clauses in the service of policy preferences should remind us that there is a real line between constitutional interpretation and argument in defense of political goals.

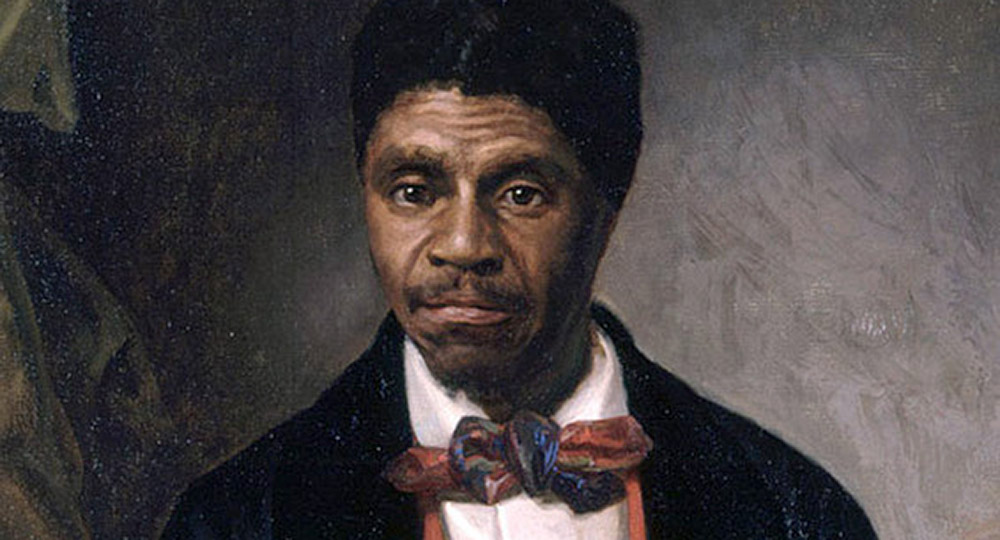

One of those efforts concerns birthright citizenship. The first sentence of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This phrase overturned the Supreme Court’s notorious Dred Scott decision (1857), which held that persons of African descent could never become citizens. When the amendment was ratified in 1868, it conferred citizenship on the newly freed slaves and marked an important turning point in the United States’s definition of “We the People.”

The language of the citizenship clause is expansive: all persons—not just members of a particular race or children of citizens—who are born in the United States are entitled to U.S. citizenship. The qualifying phrase “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was included to clarify that children born to foreign diplomats or (perish the thought) foreign invaders occupying U.S. soil would not acquire citizenship.

The authors of the amendment understood the implications of the clause: it would confer citizenship on children of people who were not citizens themselves. For the most part, that posed no problem because the United States then had an open-door policy, at least with respect to most potential immigrants. But the clause applied even to more politically controversial populations. Senator Lyman Trumbull, one of the architects of Reconstruction, responded to criticism that the clause would result in “naturalizing the children of the Chinese and Gypsies born in this country” by affirming that it “undoubtedly” would. And even after Congress passed the first significant restriction on immigration—the Chinese Exclusion Act—the Supreme Court held in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) that a child born within the United States to parents who were ineligible to become citizens nonetheless possessed birthright citizenship.

Anti-immigrant activists argue that the citizenship clause does not mean what it says. They are wrong.

In recent years, anti-immigration activists have warned of a flood of “anchor babies”—children whose noncitizen mothers travel illegally to the United States to give birth for the purpose not only of obtaining U.S. citizenship for their children but of gaining a pathway to legal residence for themselves as well. Proposals by members of Congress and conservative activists to repeal the citizenship clause in response will surely fail: there is no possibility that they can garner the required two-thirds votes from both houses of Congress. So anti-immigrant activists have turned instead to arguing that the citizenship clause does not mean what it says. They don’t deny that their targets were born here. Nor do they deny that those children are subject to the jurisdiction of the United States in the sense that they must obey federal and state law, can be the subject of child-custody or parental-termination decisions by federal or state courts, and so on. But they say that because such children may also owe obedience to their parents’ country of citizenship—if that country gives birthright citizenship to children born abroad (which the United States itself does not invariably do, as last term’s Flores-Villar case illustrates)—they somehow are not sufficiently subject to U.S. jurisdiction to qualify for citizenship because they are not subject exclusively to U.S. jurisdiction.

That position cannot be right. If it were, Congress would also have the power to withhold citizenship to children born in the United States to married couples where one parent holds foreign citizenship. After all, those children might be subject to dual jurisdiction as well. That no one is willing to go that far suggests that the desired policy outcome is driving the interpretation.

Wishful thinking similarly underlies the calls we heard this summer for the president to raise the debt ceiling unilaterally. A federal statute—not the Constitution—limits the amount of debt the federal government can incur. This past spring, the government hit that limit, raising the prospect that soon thereafter, it would be unable to pay the interest on government debt or spend money on authorized programs. At one point, the president and Congress were at a stalemate, with a majority of the House seemingly unwilling to raise the debt ceiling unless they obtained an agreement with regard to the deficit and the federal budget. Some partisans and scholars then turned to section four of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provides, in pertinent part, that “the validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law . . . shall not be questioned.” These commentators claimed that this provision allowed the president to raise the debt ceiling if doing so was necessary in order to pay the nation’s bills.

Ironically, some of the same people urging this unilateral executive action had been suspicious during prior administrations (or even during this one when it came to the president’s power to intervene militarily in Libya) of expansive claims of executive power absent congressional authorization. As with the anti-immigration forces, the constitutional text cut strongly against them: in the second clause of Article I, section 8, the Constitution expressly confides the power “to borrow Money on the credit of the United States” in Congress, not the president, and section five of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that “Congress”—with no mention of the president—“shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” Like the argument over the interpretation of the citizenship clause, the argument here was too clever by half. Not everything on which the federal government is obligated to spend money is a “debt.” Nor is failing to pay a bill on time necessarily the same thing as “question[ing]” the underlying debt.

The lesson from these two debates over the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s less familiar clauses is sobering: activists, legislators, and scholars alike often are drawn to arguments that serve their politics, but that are more clever than wise.

It was heartening to see many principled conservatives condemn the citizenship clause circumvention and principled liberals reject the public debt clause end run. They remind us that while the Constitution’s great clauses are often open-texture, they are not empty.