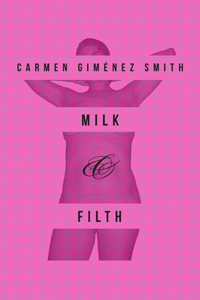

In Milk and Filth, Carmen Giménez Smith’s powerful fourth book of poetry (University of Arizona Press, 2013), the poet takes on feminism in ways both historical and personal, all through a lens well aware of both the contemporary landscape and the women who struggled before us. A 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award nominee, Milk and Filth is astonishing for the beauty of its language and the ferocity of its unflinching vision. As with any book I love, I finished it with fascination—and with questions on my mind. So I contacted Giménez Smith via email and we conducted this interview last month. Also read "My Body" — a new poem by Giménez Smith—as part of National Poetry Month.

In Milk and Filth, Carmen Giménez Smith’s powerful fourth book of poetry (University of Arizona Press, 2013), the poet takes on feminism in ways both historical and personal, all through a lens well aware of both the contemporary landscape and the women who struggled before us. A 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award nominee, Milk and Filth is astonishing for the beauty of its language and the ferocity of its unflinching vision. As with any book I love, I finished it with fascination—and with questions on my mind. So I contacted Giménez Smith via email and we conducted this interview last month. Also read "My Body" — a new poem by Giménez Smith—as part of National Poetry Month.

—Lynn Melnick

Lynn Melnick: Your poem “Diving into the Spoil” is an adaptation of Adrienne Rich’s well-known “Diving into the Wreck.” In yours, the speaker returns to the surface. Can you talk about what it means, over forty years after Rich’s poem, to find one’s way out of the wreck and spoil?

Carmen Giménez Smith: In writing many of these poems, I appropriated what many canonical and historical feminist texts promised or pointed to and then wrote a follow-up, a response or epilogue to my constant return to the poems or mythologies. I suppose I’m also attempting to represent the labyrinthine feminist trajectory that brings us to this knotty moment in which women are continuing to make great advancements in the workplace while onesies for girls have fake cotton high heels appliqués. Technological paradigm shifts that weren’t anticipated are being integrated into the movement, but the Internet has also created this gigantic arena for contempt and misogyny. The poem’s idea of finding a way out, the promise of a utopia, is the rhetorical hook. The poem’s heroine takes the treasure, steals it, and then, like the ancient mariner, wears a dark reminder around her neck. In other words, it’s not easy; it’s shitty to battle the king, and the battle is Sisyphean, and still as active as ever, but the gift is so potent, it’s worth it.

LM: With Rich in mind, and in light of your book’s opening section, which is a series of feminist, and winking, “Gender Fables,” can you speak to the lines in Rich’s poem “the thing I came for: / the wreck and not the story of the wreck / the thing itself and not the myth…”?

CGS: Those lines speak very much to my desire to unpack the problems of the female hero/villain. I certainly won’t attempt to put words in Rich’s mouth, but the wreck was the thing in the backdrop of the second wave feminism that defined her politics. These days, it’s the myth. In my essay “Drone Poetics,” I’ve pointed to Karl Rove’s statement that “We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.” That patriarchal-created reality is the world we live in, so we’re not even part of an empire anyway. Our agency as a populace has eroded to a laughable level, and thanks to a cultural tradition of American horizontal oppression, women, particularly women of color, bear the brunt of an oppressive hypercapitalist culture that relies on our self-loathing and our ability to produce more consumers with our bodies. A huge story-based machine is in place to oppress us. In this way, I guess I’m arguing for an activist/hacktivist position in which we revise the stories we buy.

LM: Your poem “[And the Mouth Lies Open]” spoke to me pretty hard with its attempt to reconcile the everyday with the fantasy of what life should be, with its managing to encompass the mundanity of life as well as its traumas and the ongoing objectification of the body. When you write of all this, do you have a balance in mind for the poem, a plan? Or do you just feel instinctually when all these elements come together?

CGS: That poem began as an address to Virginia Woolf, and then evolved into a more general address to any woman writer attempting to navigate the complexity of mental illness, work, and family. The poem also refers to Anne Sexton, a woman who was pointed to poetry as a way of processing her feelings, who instead brought the very exciting profane to women’s poetry, changed the face of it. “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker was so affecting to me because it reminded me of all of the different ways that women have resisted a world that tells them only men are artists, and all of the ways art has been wrought in history. Despite a culture that impugns the female artist, women have made art at any cost.

LM: In the smartly devious “Epigrams for a Lady,” you write that “She who does not know how to put her business on the streets ought not / to enter the art biz.” Do you think female poets are confused with the speakers of their poems more often than male poets? And, if so, how do you feel about this? Do you, or would you, mind if people conflate your work with autobiography if it is, in fact, that?

CGS: One of the book’s primary premises is that the personal is political. I think the confusion of who the speaker is in any gender has more to do with what is valued as canonical, or as one misogynist professor I had in college once said, as valued in the “Great Chain of Being.” So, to me, novels like Zoo City by Lauren Beukes, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, Emma Donoghue’s The Room, or Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers are visionary and transformative and, for this reason, canonical. They don’t speak from some commonly accepted and transparent subjectivity, and they still transform. How does this connect to your original question? I think that the canon privileges male histories, both political and private, whereas women’s same histories are seen as domestic trifles. So I intend to go as deep as possible into those trifles just as (Cuban-born performance artist) Ana Mendieta went deep into her own body as a response to male hegemony.

LM: Your poems often have a wry humor to them, which I much appreciate. And you kind of address that head-on in “Can We Talk Here,” which you note is “after Joan Rivers.” She’s an interesting—and, I suppose, surprising—icon to take on and after, in that she represents, at this point, this country’s gross obsession with celebrity and celebrity culture. That said, she was a feminist trailblazer and barrier breaker in so many ways that I think get overshadowed by her latter career and by the dismissal of older women that is common in our society. I’m curious how much of this you had in mind when you wrote the poem.

CGS: Joan Rivers is frozen in time (the 80s) to me for her feminist sensibility, and, if anything, she’s a victim of beauty and celebrity culture. I have the same feeling about Madonna, particularly the publication of Sex in 1992 because those two artists (I’m also going to have to give a shout out to Sandra Bernhard and Phyllis Diller) basically announced that they controlled the discourse around themselves, and they were unfazed by the vitriol, even used it in their work. It’s so much harder to do that now, which provokes me to do it more, not give a shit and be what I am.

LM: In the same poem you have these lines: “My parents can’t describe me. All they ever see is assimilation and coco- / nut. All they say is, ‘Why can’t you just build yourself a Trojan horse into / the big league?’” There is a lot of longing and sadness in these lines, even as they are prickly and funny. What do you think that Trojan horse would be made of? What might (or does) it feel like to ride it – in poetry life and in “regular” life?

CGS: That line has a lot going on in it. For one, I think I’m alluding to the occasional impostor syndrome that many children of immigrants feel. I was able to attend a prestigious graduate school that gave me cultural capital I would have never had access to otherwise, so I found the golden ticket in the Wonka bar. Occasionally I feel guilty that I’m not using this capital in a more saintly or financially savvy way because I have an access that my parents worked themselves nearly to death for. In my thinking, there are prescribed roles available to women of color. For this, I turn to the brilliant book Presumed Incompetent, which describes the challenges of being a woman of color in the academy. The Trojan Horse is an obedience to a sometimes degrading position. Truthfully though, my mother is happy I have health insurance, so it doesn’t often get that deep.

LM: Finally, going back to the third question of balancing all one’s desires for what a poem should be, I wonder if it is possible for you to describe your act of writing. Are there set ideas and images that you have at the outset and that you deliberately work in, or are these ideas always in the background and just sneak in? Your language is so alive and lovely, I wonder if that is what leads or if it just naturally flows from your subject matter.

CGS: Writing poetry is a very sensual, and at many stages, unconscious work for me. If I had to provide an analogy, I would say that I try to be very receptive to anything that comes into my mind as language. I have dozens of completely disorganized notebooks that I occasionally dip into. I also do a lot of different writing exercises just to keep it alive. But it’s the ear. One of my favorite recent movies is Upstream Color, directed by Shane Carruth, and it’s a beautiful allegory about contemporary life, but it’s also a meditation on what hearing does to us, how being receptacles opens the world, and I like that as a type of poetics or philosophy.