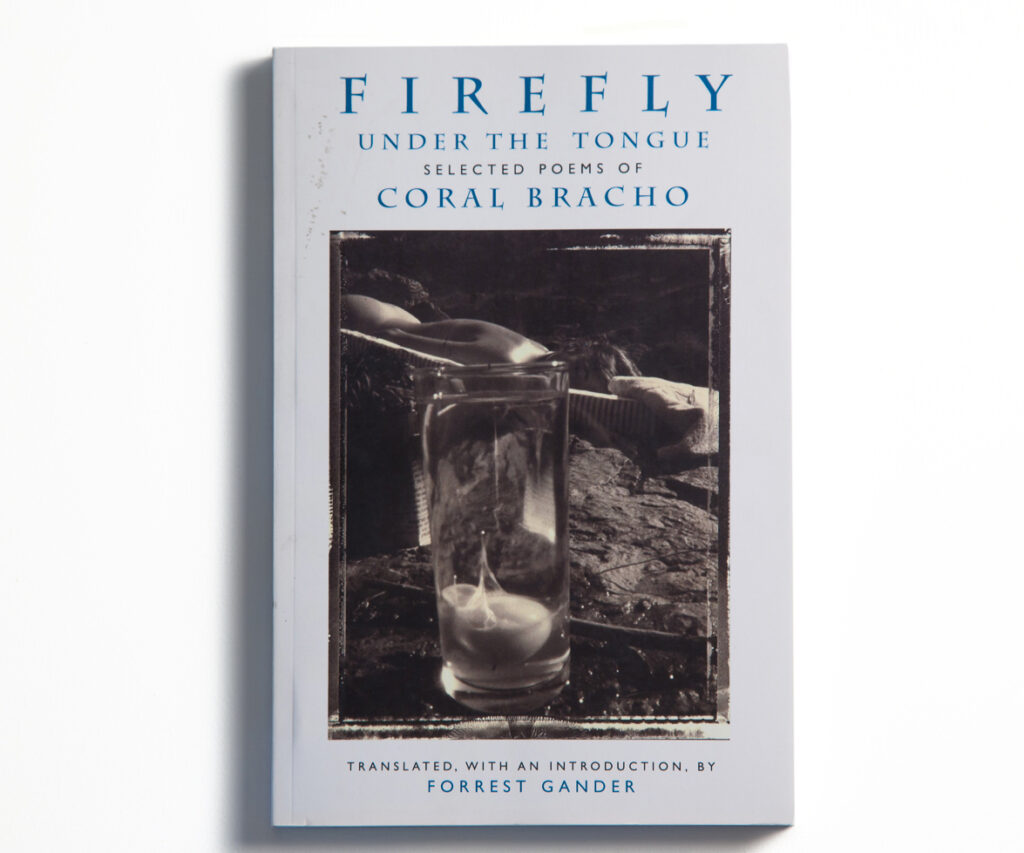

Firefly Under the Tongue: Selected Poems of Coral Bracho

translated, with an introduction, by Forrest Gander

New Directions, $16.95 (paper)

Poetry may be the most immediately sensuous literary form, but its language tends to substitute for touch rather than enact it. To place the body in close relation with other bodies and objects involves an unsettling of the self within a larger passage from identities to intimacies. Coral Bracho stunned readers in Mexico by doing just this in her 1981 collection El ser que va a morir (Being toward Death), parts of which appear in Firefly Under the Tongue: Selected Poems of Coral Bracho, beautifully translated by Forrest Gander. In Being toward Death, Bracho combines a quiet inwardness that is also a vulnerable openness: “(—Children trace their liquid howl on the bark, / as a vegetal ghost) // —The flames lick-out from the night, from its long roots. / —Its fluid / roundness, its coming to be —From what I drink, what I touch.” In this poetic speaking, mouths and hands synonymously approach a densely textured materiality. Although Bracho frequently mentions death in her poems, nothing ever quite dies in them—rather, it takes on a different life and shape: “One blink is the dream, / another is death singing / with undisguised tenderness.” Bracho’s frequent use of parentheses in earlier poems and broken narratives in later ones signal not so much interruptions as shifts. Similarly, her writing has moved over the course of nearly three decades from a spatially fluid tactility to a crystalline attention to objects in time. A poem from 1998’s The Disposition of Amber reads in its entirety: “The posture of the trees, / as gesture, / is momental.” A later book, the long poem That Space, That Garden, synthesizes previous relational modes. As with other excerpts in the collection, one wishes there were more. Recent writing in Firefly under the Tongue limns experiences of bliss with a sense of mortality. But Bracho has always had the ability to make happiness seem slightly dangerous, as her poetry doesn’t so much speak the unspeakable as voice its constant and quavering proximity.