You Animal Machine (The Golden Greek)

Eleni Sikelianos

Coffee House Press, $16.95 (paper)

In the Circus of You: An Illustrated Novel-in-Poems

Nicelle Davis and Cheryl Gross

Rose Metal Press, $14.95 (paper)

You Who Read Me with Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends

Dorothy Iannone, edited by Lisa Pearson

Siglio Press, $45 (paper)

Woman-freak, woman-beast, and woman-man: these three recent hybrid books explore radical transformations. Presenting subjects who experience everything from the disfiguring fragmentation of the freak show and peep show to the birth of a goddess outside of time, these works make spectacles of themselves and of us. All three combine graphics with text: drawings, paintings, and photographs intermix with letters, distressed newspaper clippings, stained recipes, memoir, lyric essays, and poems. By promoting a robust and textured experience of time, these particular genres reveal stories usually invisible through the lens of history, especially stories of the forces that contain women’s bodies and lives—societal mores and expectations, marriage, depression, mental illness, and abuse. Their broken narratives map territory previously unnavigable by means of traditional forms, scaffolding new connections between subject and object, selves and others.

Sikelianos begins You Animal Machine (The Golden Greek), a memoir of her exotic-dancer grandmother, by gesturing to all of human history:

I see the lines of our ancestors laid out in filaments looping here and there, bifurcating, disappearing. . . it was and is a man and a woman, two by two, each representing a small electrical hyphen of human intelligence and endeavor illuminating the path that leads to me sitting here—; men and women, each with eyes lit up for at least one moment in their lives; loving each other in the dark before the advent of writing; or a brief encounter, maybe forced, that led to the continuation of a line; these packets of genes waiting, and that uncontrollable animal urge toward making things—love, babies; the ranks moving forward and forward. . . until they reach the edges of history; and forward, farther, till they hit the periphery of family lore.

Conventional family memoirs can be suffocating for female characters, who as daughters and mothers seem to serve as human vessels, but this memoir-in-essay is an anti-memoir, mostly concerned with what we do not and cannot know, what we refuse to see. These gaps are what liberate Melena, the professional spectacle that is this memoir’s subject. Melena, a burlesque and exotic dancer, is daughter of a Greek immigrant (or refugee?), mother of three, wife of five, possessed of nineteen different names and aliases (two of which are secret and two unknown), and the grandmother of the author. “It matters,” Sikelianos tells us, “that there are holes in a family history that can never be filled, that there are secrets and mysteries, migrations and invasions and murky bloodlines. In this way we speak of human history.”

The memoir’s job is precisely that of re-membering—connecting the broken members of the family.

Sikelianos’s memoir is as much about what memory obfuscates as it is about Melena. Since no one is in possession of original knowledge, it is impossible for the memoir to do the work of remembering in the sense of recalling facts. Still, the memoir’s job is precisely that of re-membering—connecting the broken members of the family (the human family, the Sikelianos family) into a whole. Like the body of Osiris, Melena’s is severed and re-joined in her various stage costumes, most often, Helene the Golden Greek, with her scarves and her bow, or Marco the Cat Woman/Melena the Leopard Girl:

She must collaborate, disappearing, to bring the disguise to life with every part of her body’s movement or stillness, her poses, her eyes. The mask hides the mother’s mother-face. She writes the mask, the mask writers her. The longer she wears it, the more power it acquires. But the body mask is in the past, “the body of no one . . . a seizure like a cut in time. . . . [a] wild . . . history having no meaning in any present . . . [the body] has always already fallen outside memory.”

Can such a gestural work, so laced with holes, still be called a memoir? The narrator is also never sure:

Story is not the right word. History is too vague. This is a net of family giftings, woven in darkly luminous filaments, the shirt daubed with Nessus’s blood that scorches the skin, wounding the susceptibilities. But what is the key that turns the lock of the poison dress? Who is us? (Me and my mother)

Rather than a memoir, then, we’ve got a wound. Again and again, Sikelianos refers to a wound or hole, suggesting the vagina from which packets of genes emerge, the tunnel leading to the dark and the underground, as well as the gap in the net of wholeness that refers to the wholeness itself. For example, the father of Melena (whom he named Helene) is introduced like this:

He burrowed up under the map like a mole and burst the topography, shredding the paper, blasting a man-sized hole in the earth at his exit point—a hole in which no daughter can hide. Since he is a lost man, everything in this book is speculation.

To make up for the lack of known human progenitors, we are given archetypes—Ceres, Persephone, the corn mother. In lieu of a family legacy—land—we are given the underground. The book is a search for “the one story that will anchor your life,” yet it evades that motive. It is about the multiplicity of stories, and the story as mirage, as temporary placeholder. In a startling juxtaposition, the book ends with a photo of Melena/Helene as Marco the Leopard Girl, claws posed, mask intact. The cat, the animal, has no past. We’ve lost her.

Image courtesy Coffee House Press.

One of the most common ways that women have searched for “one story that will anchor the rest of your life” is through marriage. Sikelianos, in discussing Melena’s five marriages, notes that she is “trying to make sense for her, build her a net that connects to everything, let her slide around in an elegant way in daylight.” Yet she follows this intention with William Blackstone’s observation that in marriage “The husband and the wife are one, and the husband is the one”—a singularity that often results in tremendous deformation of the wife. This particular deformation, and the resultant divorce, fuel Davis and Gross’s In the Circus of You. The book narrates the dissolution of a marriage and a self, and the subsequent creation of grotesqueries of inner figures that emerge within the brokenness.

Unlike Sikelianos, who engages the motif of the peep show to explore what we intentionally do not see—after all, the spectacle is all about the desires of the viewer, not the humanity of the object of the gaze—Davis and Gross use the freak show as a means of communication and empathy. In their note “The Making of In the Circus of You” at the end of the book, they explain, “Like any sideshow, the more you gaze the more you become what you look at; if we are lucky, then we are all looking towards each other—we are becoming a little more human.” Their premise is that the sideshow freak, by nature of her freakishness, is gazed upon until we recognize the human in the freak, the freak in the human. The narrative arc of In the Circus of You is neatly contained in this wild collection of selves and others. Its four sections explore different dehumanizing forces that prevent full participation in human society: the day-to-day failures of the self in the context of the dissolution of a marriage; a historical survey of humans whose physical abnormalities were highlighted in circus “freak shows”; the devastation of poverty and post-partum depression; and, in the wake of these, the slow recuperation of the self.

The collection begins with a prelude to the self-destructing marriage, in “Wings Inside Our Stomachs”:

I’m not a monster, you say. The little girl in me agrees—

sits next to your boy-self on the curbside

of our childhoods. I once believed the hole in you would hide

the girth on me, but combined

we are one jagged edge placed next to another. All rip and twin—

ball of barbed wire

passed between bloody fingers. We never meant harm—marriage

just was

n’t our game

When the female subject of You Animal Machine is dismembered or fused with animal bodies, she takes on their characteristics and powers in order to escape from husbands and patrons by becoming an object of sexual fantasy. But the beasting of the woman in Davis and Gross’s In the Circus of You seems to imply a feminine failure, an inability to be a “citizen” of a marriage. The speaker resists this transformation, as useful as it might be to her. In “Gifts of a Shape-Shifter,” the speaker notes:

I want a different shape to fit my bones. I’m not

a bitch, I bark. Teeth nipping your ears. Say I’m not. Not.

The taste of blood. You want reasons for a feeling—here are reasons: love’s not nice, it calls me names—makes

a game of me. Makes me hungry and hurt where I’ve bitten

myself. I catch sight of us in a mirror—in my mouth a bird—

killed and gifted.

Image courtesy Rose Metal Press.

Contrast this passage with Sikelianos’s memoir, in which Helen/Melena escapes from marriage five times. Helen may be a beast, in the sense that she is cruel and unattainable, her physicality gazed upon with desire, but she is not a “freak” even though, the memoir tells us in a section with that word as its title, her fourth husband, the “dwarf,” was considered to be a freak at the time. (Sikelianos is also referring to a movie which previewed in 1932.) In her use of this term, Sikelianos seems to mean “I could not imagine his sexual citizenship.”

“Like any sideshow, the more you gaze the more you become what you look at.”

Some of the non-human or extra-human creatures in In the Circus of You, such as the shape shifter, reflect the speaker’s emotional turmoil, but a number of them, such as those in section II (“Recruiting talent for the appropriation circus”), are based on real-life American and international sideshows. These poems are some of the most moving, and they display restraint and self-reflective understanding, drawing attention to the limits of the speaker’s use of her sideshow metaphors. “Ella Harper: Lessons in Accountability—or—Why Students Make the Best Teachers,” contemplates “Camel Girl” Ella Harper, who was born with knees bending outward and is billed as a quadruped:

It is her shy smile—straight bangs—overbite that remind me, no matter how I’ve been called an animal, I’ve never had to fight a camera for human recognition that I am of their kind.

The facing illustration depicts an elephant, a lion, and, in between, a girl, standing on crutches, her knees creating an “x” of her upright legs, as if crossing out her humanity.

Image courtesy Rose Metal Press.

This novel-in-poems is not as linear as it first appears to be (or as the subtitle “novel” suggests it will be): it does not begin from a state of wholeness, nor does it end there. Each section displays brokenness and integrity together, and the final two sections contain the poison and the antidote at once. Section III, “The Clown Act,” chronicles the psychological disintegration resulting from the speaker’s experience of post-partum depression and the poverty that impedes treatment. “As the Pill is Taken” describes being given an inappropriate medication, one that treats adult bed wetting, because it is what the speaker can afford:

Swallow, Doc says. Sure it’s not right, but it’s what you can

afford and it will stop the mania by coating you

in warm wax. Your mind a candle

Wouldn’t you like that? A

flame concentrating

on the wick. The

rope. Wouldn’t

you like to

be a single

cord tied

to what

fuels

you? Wouldn’t you? Like that. And swallow. Down—

Soon the speaker decides to stop taking all the pills in “Clowns Promise What Can’t Be Delivered,” since she has decided, albeit in parentheses, “(I miss myself more than I’ll ever miss us).”

Most strikingly, this collection avoids moralistic conclusions or sermons on the merits of suffering. There is no greater wisdom or higher morality here. There is only the human, in all its brokenness and strength, and nowhere is it as lovely as in the last poem, “Reborn Inside-Out, My Life Is Explained to Me by My Six-Year-Old Son”:

What is

left of me, my son walks next to on his way to school. He tells me he’slearned, Where rain and babies come from; he says, It’s all the same,

really. Inside. Outside. He doesn’t notice any difference. He says,Race ya, and we run into a storm of babies—falling. Life absorbs

quickly as water into earth and all is an unstaged show of growth.We will die, Mom, he says, But like star-matter we’ll regenerate. Why

do you think that is? I ask him. So we can find the joy in it, he tells me.Our story will happen again.

The book affirms regeneration—not just of the broken female psyche, the broken family and marriage, but of all of us. We are made of star matter and are thus united in brilliance. We will happen again, and with joy.

This movement toward unification of self and cosmos is also the principal force of Dorothy Iannone’s You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends. Iannone’s collection is a truth-seeking, truth-making “ecstatic unity” narrated through image and text. Ecstatic unity is, for Iannone, becoming one with the other, a complete intimacy and “sweetness outside of time,” a state of wholeness and completion. Drawing on Tibetan Buddhism, Iannone suggests that the longing for this sense of completion, this complete intimacy, “was already within myself.”

Iannone’s joyful, colorful, explicitly sexual collection reproduces many unpublished or long out-of-print works, in their entirety or as substantial excerpts, from Iannone’s fifty-year career. It begins with the carnal origins of Iannone’s search for ecstatic unity in An Icelandic Saga, an epic depiction of her voyage into life with Dieter Roth, and its open-ended conclusion is characterized by movements toward the divine—still embodied, of course, in various works from the last ten years. The collection itself is only loosely chronological; time, for Iannone, is not linear but simultaneous. A single story—the quest—is retold again and again with varying characters, or versions of the same character.

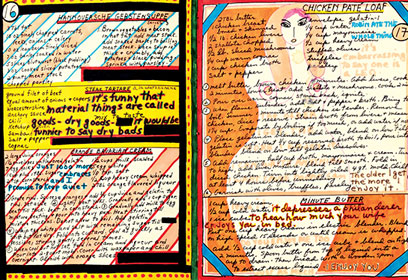

Iannone juxtaposes large ideas about the nature of human attachments alongside the banal work of cooking.

If Sikelianos is interested in showing how we refuse to see or cannot see, and Davis and Gross are concerned with empathetic viewing, Iannone’s so-called sexual “exhibitionism,” where intimacy itself becomes the spectacle, involves the act of perceiving rather than what is perceived. Here, at least three kinds of boundaries are transgressed. First, Iannone effectively collapses the boundary between man and woman—in many of her images, the genitals of the couples are exchanged or blended. Second, she erases the line between what is hidden and what is visible: incongruous poses and colorful genitalia pop up everywhere, rendering clothing irrelevant. Even when body parts enter other body parts, the pieced body is luminous, so the entering does not impede our vision. In this way, sight and sensation merge. Third, Iannone’s image-text collapses the boundary between subject and object, reader/viewer and creator. The reader/viewer is always complicit. Hence the title of this collection.

The trans-gender, trans-genre aspects of the book provide a dynamic contrast to moments that describe the gross materiality of being a woman, especially a woman of means, or in the chapter “Cookbook,” the materiality of being a woman who cooks. Here the narrator is producing the food the body needs in order to live while agonizing over her partner’s infidelities and neglect and her feeling of domestic entrapment. While she rages and ponders the hand-written pages of recipes for Rice Alla Milanese, Fennel and Chard Au Gratin, Lapin Chasseur, or Escargots Bourguignonne, she notes,

For a man who rejoices in his contradictions, you are quite an absolutist.

2 cups dry white wine

1 six ounce can tomato paste (I mean sometimes)

2 bay leaves

1 13 ¼ oz. can chicken broth

3 Tlb. Mustard . . .

Along with her notes to her partner, she includes notes on her own state of mind—“It shames me to dissolve”—and speaks to herself: “to become famous is really not much of an [a line descends the page, then the sentence continues] ambition. A little gelatin might go a long way with me. But perhaps that’s just another contradiction.” For her readers, she says of a particular mark on the page, “that’s spit.” These ruminations are hand printed in colored inks:

“ISN’T JEALOUSY A PAIN IN THE ASS?” [in pink]

“ONCE [a red square around the word “Once”, then back to pink] I WAS ECSTATIC AND NOT JEALOUS. THE TRICK IS TO AVOID A DECLARED ALLIANCE. I THINK.”

“I SIGH LIKE A VIRGIN. DO YOU EVER SIGN?” [in gray]

As I read with her and cook, I feel the need to answer, because, as the book title notes, she’s talking to me, too.

“How does one undeclare, Goddammit?” [in pink]

Through a rich and textured stream of consciousness, Iannone’s text contrasts large ideas about the nature of human attachments and self-fulfillment with the incredibly banal, precisely timed work of cooking. It works.

Excerpt from “A Cookbook,” 1969 by Dorothy Iannone, in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, Siglio, 2014. Courtesy of the artist, Air de Paris, Paris. Photo Hans-Georg Gaul.

The collection nears its end with instructions for the beautiful “Darling Duck”—”inspired by centuries of yearning for the eternal duck” (a description resonant with punning)—and the piece “For Emmett, Who Hasn’t Changed A Bit.” Her instructions explore the indivisibility of the body and the spirit, of eternity and temporality, of sex and the integrity of the one:

So you see, strictly speaking, there need be no separation between eating and meditation, or anything else at all . . . to be aware to this degree, of course, takes a lot of practice (and open-heartedness too). needless to say I’m just a beginner but if you’d like to hear a little more about practicing while enjoying your succulent duck, I’d like to go on telling you

For those new to “reading” graphics, the collection ends with a very helpful essay by Trinie Dalton, which offers strategies for appreciating Iannone’s temporality, her handwriting and decorative flourishes, and her humor. There are also interviews with Dorothy Iannone by Trinie Dalton, Maurizio Cattelan and Noa Jones, which place Iannone within (or outside of) contemporary movements in painting, folk art, modernism and graphic art. The essays and interviews also discuss Iannone’s work in the context of feminism.

Excerpt from “For Emmett, Who Hasn’t Changed a Bit,” 1992 by Dorothy Iannone, in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, Siglio, 2014. Courtesy of the artist, Air de Paris, Paris.

This aspect of feminist work perhaps accounts for the fact that all three of these books resist conclusions. I rejoice that “Our story will happen again” in Davis and Gross’s Circus, and I am grateful for the act of generosity with which Sikelianos ends her Animal Machine: with Elayne and Yvanne’s response to the book about their mother. I appreciate the fact that there is no “last word” in any of these collections—the openness that began the works also concludes them. They reach a sense of artistic creation as a door or portal, opening into a space more integrated and compassionate than the one the reader inhabited before.