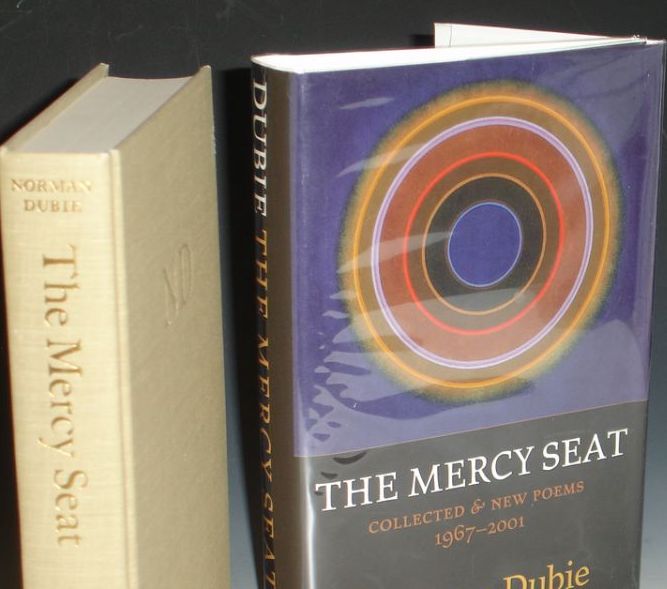

The Mercy Seat: Collected & New Poems, 1967-2001

Norman Dubie

Copper Canyon Press, $30 (cloth)

Though it is often perfunctory shorthand to invoke Whitman when speaking of a contemporary U.S. poet, in discussing Norman Dubie, a single parenthetical statement from the fifty-first section of "Song of Myself" applies: "(I am large, I contain multitudes.)" Dubie has a singular talent for inhabiting a persona and making convincing representations of another person's life, taking on a different view and experience of the world. He prefaces a poem in this vast and wonderful new volume with an epigraph from Delmore Schwartz: "They were with me, and they were me… / As we all moved forward in a consonance." This final word, "consonance," means harmony and concord; but its musical connotations, its Latin root in words meaning "to sound together" link it, too, to empathy, the act or experience of resonating with or "feeling in" another, in order to (paraphrasing the OED) "identify oneself with (and so fully comprehend)" another person. Dubie's identifications are so evocatively represented, and the voices of his poems so varied, that one almost believes his subjects actually "were with [him], and they were [him]."

One of two poems dedicated to a friend who died at age twenty contains these sober lines:

We will all be lost,

Even down to the very last memories that others have

Of us, and then these others who survived us, they

Too will be lost.

Dubie's perspective, mournful and unsentimental, is predicated on a broad historical vision. Sometimes he writes in the assumed voices of prominent figures—Czar Nicholas of Russia, Herman Melville, the painter Frida Kahlo; more often the character is unknown to the reader, a voice from literature or from a painting, or an anonymous, invented participant in or witness to some historical period or event; sometimes one assumes the character is a friend of the writer, or a glimpsed or imagined stranger. "The Czar's Last Christmas Letter: A Barn in the Urals," the poem in the voice of Czar Nicholas, is written in the simple language and direct address of a son's letter to his mother, formed in unrhymed two-line stanzas. By assuming the identity of the historical figure, the poem personifies the whole complex of his moment, embodying the past and thereby going far deeper than a simple recitation of events. Dubie's Nicholas gives the reader a recognizable empathetic subject, a confused, despairing, doomed individual, at once within the matrix of historical fact and abstracted from it. In this way, again and again, Dubie takes his reader into the longing, joy, and loss of his subjects.

It is the tenderness of his identifications that makes Dubie's work so extraordinary. A poem of the formal economy of "A Grandfather's Last Letter" becomes vast through its counterpoint of the said and the unsaid. Early on, the silence of a stanza break creates a poignant interregnum within the poem: "I have closed your grandmother's front rooms. // I know you miss her too." This pause has a palpable weight and pity, the blank line encompassing so much in the lives of grandfather and child, its extended silence like the crack of sticks knocked together in a Noh play. The poem wanders, then, through anodyne descriptions of a familiar garden and the animals that inhabit and visit it—moles, pine martens, an owl, a mockingbird. After observing that "Molehills can weaken a field so that a train / Passing through it sinks suddenly, the sleepers / In their berths sinking too," the letter comes finally to the granddaughter's fear: "You said you worry that someday I'll be dead also! Well, / Elise, of course, I will." The exclamation mark suggests her fear is ungrounded, but the grandfather's answer is emphatic and direct. The slow descent over the rustling s sounds of his reply—"Well, / Elise, of course, I will"—and the pointed pauses at the three commas within the short sentence, again open space within the progress of the poem, and allow Dubie to draw it to a beautifully spare, sympathetic close:

I'll be hiding then from your world

Like our moles. They move through their tunnels

With a swimming motion. They don't know where they're going –But they go.

There's more to this life than we know. If ever

You're sleeping in a train on the northern prairies

And everything sinks a little

But keeps on going, then, you've visited me in another world –Where I am going.

His choice not to hide the reality of his approaching death, and the fact—held within the poem's title—that this is his last letter, confer a kind of heroism on the certainty of these closing words. Like the moles, the grandfather does not know where he is going, but he knows he must go.

The Mercy Seat is Dubie's first book in more than ten years, and his first to be published by Copper Canyon Press. It contains poems from each of his seventeen prior volumes, as well as nearly one hundred pages of new work; the poet has said there is nothing he regrets leaving out of the book, and that everything he still respects as a poem after thirty years is collected here. A little over 400 pages, it is a substantial and handsome production, one of the first set of Lannan Literary Selections, a group of five books of poetry to be supported each year under a new arrangement between Copper Canyon and the Lannan Foundation.

One of the most affecting of the new poems is an elegy for Dubie's brother, which demonstrates well the ease and directness of his language and his ability to imaginatively immerse himself in a scene, in this instance directly addressing his brother through a vividly evoked memory. The poem differs from the majority of the persona poems in that its subject is the speaker himself as a young boy; it enacts a distant mirroring, rather than an immediate identification. The poem slips between freezing nights, one in the present, two others in the past. Shifting between these settings, the poem confounds a clear line between time past and present, and hints, too, at a kind of convergence of experience and perception between the brothers. "I awoke, did / You know, just as you died. Later I was told / That it rained quietly all over Manhattan." The surviving brother is walking "awhile, maybe as high as the tree line / … / To speak with you," and as the poem shifts between past and present, the description of the snowy night the speaker walks in merges with the remembered nights, so that it becomes difficult to separate them. "The cold river has a lashing movement like cilia / And we can see our breath in the air"—although this sentence begins the first memory's recall, its tense elides present experience and memory. The second memory is of standing out in the cold with his brother on a dare: "Once we waited outside on the porch / Knowing our ears were badly frostbitten":

You begged me to stay out longer

I would have actually left you there…

but now

I am still preparing to leave, to return

To a heated kitchen where dried marigolds stab the ceiling.………………………………………………………..

Then you smile at your feet, laugh,

Run up into the orange light that spills

From the opening door.

Again the broad distinction between past and present is disrupted, as the poet finds himself "stand[ing] in snow / And watch[ing] the door now being closed behind you…." So the snowy night he wanders in at the poem's beginning, in search of some kind of consolation and communion, closes the door of death and memory, finally separating the brothers. The violence of "dried marigolds stab[bing] the ceiling" plays against the domesticity of "a heated kitchen," as the brother's sudden sprint indoors—the playfulness and joy of it—is poised against the solemnity of the poet's experience of the freezing night. It is much easier for the brother to leave than it is for the poet to be left alone, "watch[ing] the door now being closed"—after all, the brother has no choice; he doesn't know where he's going, but he goes.

Dubie has for many years practiced within the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, and he dedicates The Mercy Seat to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. In the Bodhicaryavatara, a primary text within all schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the poet-monk Santideva advised exchanging oneself for others. He asked, "Why can I not also accept another's body as my self in the same way [that I identify with my own body]?" Santideva describes our habitual self-cherishing as a learned response; he suggests that it is through habituation that we become exclusively identified with our bodies, with these particular hands and legs and no others. "Therefore," Santideva continues, "in the same way that one desires to protect oneself from affliction, grief, and the like, so an attitude of protectiveness and of compassion should be practiced towards the world."1 Elsewhere in the text, this idea is put graphically by describing how we might reach down to touch and ease our own injured foot—this is seldom a considered response, more a natural reflex to discomfort or pain. Santideva argues that we can learn to identify ourselves with others—and the Buddhist tradition of Bodhicitta training (fluently popularized in several books by Pema Chödrön and the Dalai Lama, among others) has developed practices that strengthen this other-identification and help us go beyond our habits of self-cherishing. It is likely that Dubie is familiar with Santideva's text, and even more likely that he knows the practices it enjoins, which are taught widely in all schools of Tibetan Buddhism. In light of this, Dubie's texts might be seen as more than dramatic monologues: they would then take on the aspect of spiritual exercises of identification, exchanges of self and other.

A Buddhist myself, I had read little of Dubie's work before seeing his picture alongside a poem in a recent issue of American Poetry Review.The photograph caught my eye because the poet's hands were held distinctively, palms upright, fingers loosely interlaced toward their tips, a movement towards a ceremonial gesture in a Buddhist ritual of offering the universe. This is an apt emblem for The Mercy Seat which, through its careful inhabitations and remarkable tenderness, offers the universe: clarified, humanized, enlarged.

Note

1 Bodhicaryavatara 8: 113, 117.